crowdsourcing |ˈkroudˌsôrsiNG|

noun

the practice whereby an organization enlists a variety of freelancers, paid or unpaid, to work on a specific task or problem

Social scientists have traditionally felt a need to tightly control how they get their data, who should provide the data and how are seen as key features of good research. But, we might take note of the ways other scientists (biologists, astronomers, mathematicians, ornithologists, and geologists, for example) are capitalizing on the lived experiences of people to help them collect and analyze data on natural phenomena.

The Case of Citizen Scientists

Many research projects now involve collecting or analyzing huge amounts of data, and both tasks are sometimes beyond the resources of an individual researcher or research team. Crowdsourcing the research tasks is being used in an increasing number of projects, mobilizing the general citizenry’s interest in science.

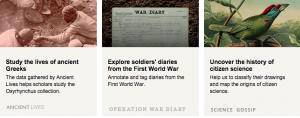

There is one web-based platform that has facilitated these research tasks; check out Zooniverse, which creates citizen science websites that allow anyone with an interest to participate in research online. These projects call on citizen scientists to help with data analysis. One recent example is Snapshot Serengeti, a website with photos taken in Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. Anyone with an internet connection can help classify the different animals caught in millions of camera trap images.

Crowdhydrology

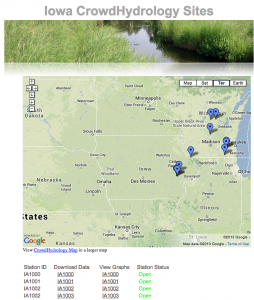

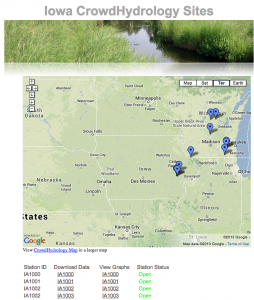

Chris Lowry a University of Buffalo assistant professor of geology has developed Crowdhydrology, a project that enlists hikers, fishermen, birdwatchers, school kids and nature-lovers to monitor stream levels in NYS, Michigan, Wisconsin and Iowa. The idea is simple ~ at each site there is a giant measuring stick and a sign explaining how passersby can text water levels and stream locations to researchers. Citizens in this project participate in data collection, contributing to research on hydrology. The data collected are public and available on the CrowdHydrology website, which describes the project thusly…

Chris Lowry a University of Buffalo assistant professor of geology has developed Crowdhydrology, a project that enlists hikers, fishermen, birdwatchers, school kids and nature-lovers to monitor stream levels in NYS, Michigan, Wisconsin and Iowa. The idea is simple ~ at each site there is a giant measuring stick and a sign explaining how passersby can text water levels and stream locations to researchers. Citizens in this project participate in data collection, contributing to research on hydrology. The data collected are public and available on the CrowdHydrology website, which describes the project thusly…

“The CrowdHydrology mission is to create freely available data on stream stage in a simple and inexpensive way. We do this through the use of “crowd sourcing”, which means we gather information on stream stage (water levels) from anyone willing to send us a text message of the water levels at their local stream. These data are then available for anyone to then use from Universities to Elementary schools.”

“The CrowdHydrology mission is to create freely available data on stream stage in a simple and inexpensive way. We do this through the use of “crowd sourcing”, which means we gather information on stream stage (water levels) from anyone willing to send us a text message of the water levels at their local stream. These data are then available for anyone to then use from Universities to Elementary schools.”

This is the interface that allows anyone to view or download the data.

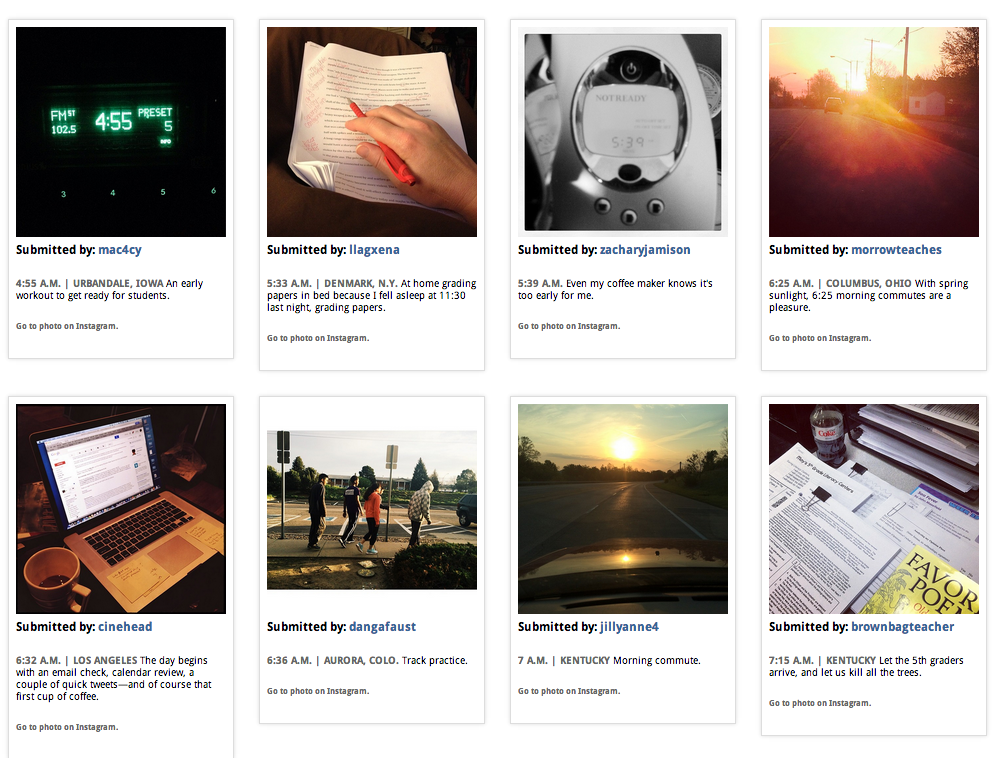

Crowdsourcing for Social Science Research?

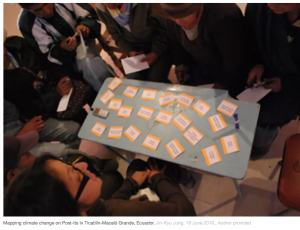

So imagine how social scientists might use crowdsourcing to investigate social issues and human phenomena. One example is a project in Egypt that gives women an opportunity to document rape, harassment and assault ~ Harrassmap tracks incidents of sexual harassment in the Greater Cairo area with the goal of understanding and changing the social acceptability of gender based violence. Social phenomena that are experienced or witnessed (safety, anxiety, happiness, bullying, crime, kindness, road rage, drug use, oppression) are all potentially chronicled, mapped and understood through crowdsourcing.

Also, check out the humanities projects on Zooniverse.

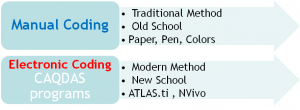

A key issue in the successful use of crowdsourcing in the social sciences is that scientists do retain some control of the research questions and what counts as useful data, crowdsourcing as data collection ought not to mistake participation in data generation with expertise in the research topic.

Follow

Follow

“The CrowdHydrology mission is to create freely available data on stream stage in a simple and inexpensive way. We do this through the use of “crowd sourcing”, which means we gather information on stream stage (water levels) from anyone willing to send us a text message of the water levels at their local stream. These data are then available for anyone to then use from Universities to Elementary schools.”

“The CrowdHydrology mission is to create freely available data on stream stage in a simple and inexpensive way. We do this through the use of “crowd sourcing”, which means we gather information on stream stage (water levels) from anyone willing to send us a text message of the water levels at their local stream. These data are then available for anyone to then use from Universities to Elementary schools.”