Researchers are egocentric… the research they do stems from their interests and motivations. That’s a given. Within interpretive research methodologies this egocentric position is tempered by the interpersonal intersection of researchers’ interests with those of their research participants. Mostly I am a researcher, but I have also been a research participant and these different vantage points provide useful lessons for thinking about how we conceptualize research participants’ engagement with us and how we treat those who participate in our research.

Researchers are egocentric… the research they do stems from their interests and motivations. That’s a given. Within interpretive research methodologies this egocentric position is tempered by the interpersonal intersection of researchers’ interests with those of their research participants. Mostly I am a researcher, but I have also been a research participant and these different vantage points provide useful lessons for thinking about how we conceptualize research participants’ engagement with us and how we treat those who participate in our research.

In general, the interests of the researcher are more important, and procedures to protect research participants are institutionalized through research review boards. For example, research participants’ identities are anonymized to encourage them to participate and protect them from harm, embarrassment, possibly even legal sanctions should the details of their lives become known. (Whether this makes sense is debatable ~ for a good discussion see Jan Nespor’s article Anonymity and place in qualitative research.)

But, equally important is the shield anonymity provides the researcher, shielding them from research participants’ challenges if and when they see how their experiences, thoughts, and emotions are used as data, as well as shielding them from professional critique since data sources (and often data) are held in secret (this is, in part, the current criticism leveled against Alice Goffman). I was able to read the research report of the study I participated in because I know how to access research, cultural capital that researchers might safely assume (hope?) most research participants don’t have.

Narratives of Research Participant Reaction

Here are three sketches of research participant reaction to a published account of the research in which they were involved. All are real. There are a number of lessons to be learned, but I will draw out just a couple.

1. In an introductory doctoral level interpretive research course students read Lois Weis’ Working Class Without Work, a study of an upstate NY high school. A student in the course had been a student in that high school and felt Weiss had understood well some of the gender related occupational aspirational conflict, but demonstrated misunderstandings of the role of the school in students’ future aspirations.

2. I read the dissertation, the report of the research I participated in, and found conversations between myself and the researcher that were not about the research focus had been included as data to corroborate evidence of my behavior and motivations as a mother. I was unaware of this until I read the completed dissertation as neither the analysis nor final dissertation were shared with the research participants.

3. A doctoral student used narrative inquiry to investigate parental experiences dealing with adult children with mental illness. His decision to use a first person story telling strategy was seen as misrepresentation by one parental participant who withdrew consent for including their data in the study.

Involving Research Participants to Get It ‘Right’

As researchers we want to get it as ‘right’ as we can and there are a number of strategies often invoked to do so. The most common are developing a habit of self-reflexivity (often manifest in journal writing), member-checking (an unfortunate term introduced by Guba & Lincoln), using key informants, and peer debriefing. These strategies are of value only if we as researchers practice them seriously.

Member-checking or informant feedback (the term I’ll use) is when researchers share research data, analysis or reports with participants to ensure categories, constructs, explanations and interpretations “ring true” and to explore what might be missing. This is a much talked about and seldom used strategy.

I suspect most researchers avoid informant feedback because it entails: the possibility of creating more, new data (like in sketch #1 and #2); invites potential disagreements and conflict with research participants (like in all three sketches); and invites research participants to opt out of the research study should they not like what they see or how they are represented (like happened in sketch #3). I also suspect most researchers do not see the value in the iterative process of multiple engagements with research participants in the space of data making and interpretation, seeing them as worthy of one but not multiple viewings (like in sketch #1 and #2). Within any interpretivist or critical research methodology this is a contradictory stance, and in establishing respectful relationships with research participants this is a disrespectful stance.

I suspect most researchers worry about the purpose, conditions and consequences of seeking informant feedback ~ can research participants give informed, useful feedback? should I change what I’ve written? does the research participant have veto power? will I destroy the rapport I have if research participants don’t agree with my analysis? Informant feedback is more likely to lead to confusion and contradiction than confirmation and clarity ~ a situation, which I have argued in delineating the process of triangulation, that ought to be invited not avoided by researchers. This is critically important. If researchers use informant feedback they should think in advance how feedback will be used and to be transparent with research participants about that.

It is also critical to care about whether you are getting it as ‘right’ as possible, and that means not avoiding informant feedback because it may challenge your ideas. Regrettably, this avoidance is safeguarded by the conventions of anonymity and confidentiality that shield researchers from engagement with research participants who cede their right to engage publicly with the researcher by agreeing to those conventions ~ a Gordian knot.

Presentation of Self as Researcher

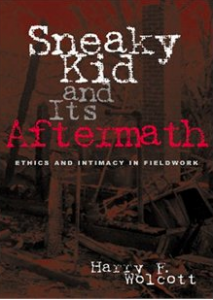

I suggest novice researchers develop a 30 second or so introduction of themselves as researchers to be used in the research context. A reminder to all that you are here as a researcher and what you are interested in… over the course of a research study it will be needed less and less but it should also be a reminder to self.  If we have extended interactions with research participants it is easy to forget that we are researchers and not friends, neighbours, confidants, compatriots, lovers, and so on. We may become those things, but then we are no longer just researchers and the challenge of distinguishing what is within the parameters of the research becomes cloudy, and we may enter into a murky moral ambiguity of ethics and intimacy. (The classic example of this is Harry Wolcott’s relationship with Brad, summarized from his perspective in his book Sneaky Kid and It’s Aftermath.)

If we have extended interactions with research participants it is easy to forget that we are researchers and not friends, neighbours, confidants, compatriots, lovers, and so on. We may become those things, but then we are no longer just researchers and the challenge of distinguishing what is within the parameters of the research becomes cloudy, and we may enter into a murky moral ambiguity of ethics and intimacy. (The classic example of this is Harry Wolcott’s relationship with Brad, summarized from his perspective in his book Sneaky Kid and It’s Aftermath.)

Researchers bear greater responsibility than research participants to maintain clarity about their role and their legitimate access to or defining what is data, what is within the boundaries of the research project. In sketch #2, some of my conversations with the researcher had nothing to do with the research topic. I gave this no thought at the time but implicitly assumed they were interactions between if not friends then perhaps a professor and doctoral student, the other most significant roles we played in relation to one another. Even as an experienced researcher, I was naive as a research participant and let the researcher in on too much of my life ~ even being ‘friends’ on Facebook during the research to then be unfriended upon completion of the research project. I mistook this gesture as ‘friendship’ when in hindsight it was data collection, albeit never negotiated as such with me.

Being clear that we are researchers should be ever present in our minds, but as researchers we need to insure it is ever present in research participants’ minds as well. “Anything you say [or do] can and will be used as data by me” might be more useful at protecting research participants than many of the promises institutionalized by research review boards.

We should remind ourselves…

narcissism should not prevail

and being a researcher is simply not a license to tell all.

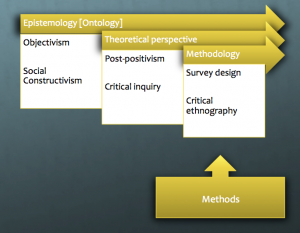

I find Michael Crotty’s definitions and relationships among the elements that frame research helpful. See this image and here, for a short note on this.

I find Michael Crotty’s definitions and relationships among the elements that frame research helpful. See this image and here, for a short note on this.

Follow

Follow

If we have extended interactions with research participants it is easy to forget that we are researchers and not friends, neighbours, confidants, compatriots, lovers, and so on. We may become those things, but then we are no longer just researchers and the challenge of distinguishing what is within the parameters of the research becomes cloudy, and we may enter into a murky moral ambiguity of ethics and intimacy. (The classic example of this is Harry Wolcott’s relationship with Brad, summarized from his perspective in his book Sneaky Kid and It’s Aftermath.)

If we have extended interactions with research participants it is easy to forget that we are researchers and not friends, neighbours, confidants, compatriots, lovers, and so on. We may become those things, but then we are no longer just researchers and the challenge of distinguishing what is within the parameters of the research becomes cloudy, and we may enter into a murky moral ambiguity of ethics and intimacy. (The classic example of this is Harry Wolcott’s relationship with Brad, summarized from his perspective in his book Sneaky Kid and It’s Aftermath.)

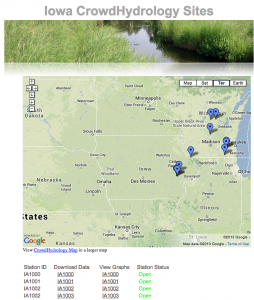

“The CrowdHydrology mission is to create freely available data on stream stage in a simple and inexpensive way. We do this through the use of “crowd sourcing”, which means we gather information on stream stage (water levels) from anyone willing to send us a text message of the water levels at their local stream. These data are then available for anyone to then use from Universities to Elementary schools.”

“The CrowdHydrology mission is to create freely available data on stream stage in a simple and inexpensive way. We do this through the use of “crowd sourcing”, which means we gather information on stream stage (water levels) from anyone willing to send us a text message of the water levels at their local stream. These data are then available for anyone to then use from Universities to Elementary schools.”