I encourage you to get your library to purchase the new memoir by Staughton and Alice Lynd. EWR

Friends,

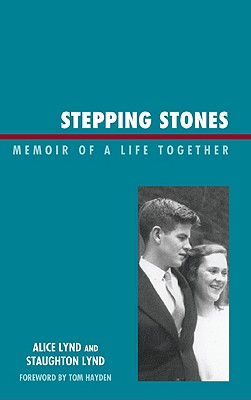

Greetings. Alice and I have written a joint autobiography entitled Stepping Stones: Memoir of a Life Together. We need your help in getting the book into the hands of the young people for whom it is most intended.

The book begins with a lovely Foreword by our longtime colleague, Tom Hayden. Then come chapters, some written by us both, some by one of us, some by the other. The chapters are grouped in the following sections:

Beginnings (our families, Staughton as a “premature New Leftist” and Alice on “Music and Dance and Discovering Childhood,” how we met and fell in love);

Community (our three years in the Macedonia Cooperative Community in the hills of Georgia);

The Sixties (among other matters, Mississippi Freedom Summer, a trip to Hanoi, Alice’s work in draft counseling and how it planted in our minds the idea of the “two experts” — the professionally trained person and the counselee, client or fellow struggler — who work together);

Accompaniment (how we found our way beyond the Sixties by doing oral history and then law together, with chapters on Nicaragua and Palestine);

The Worst of the Worst (representing and learning from prisoners);

Afterwords (a poem, retrospectives, Alice’s wishes for our daughter Martha’s marriage).

We had some difficulty finding a publisher. At length we signed a contract with Lexington Books. Lexington has produced an attractive hardback edition. On the front cover there is a photograph of the two of us on the day we married (looking very young) and on the back cover a picture taken at our 50th wedding anniversary.

The problem is that this hardback edition is intended for academic libraries and costs $70. Perhaps in part because of the current recession, we have been told that a paperback edition will be forthcoming only if orders from libraries are substantial.

This is where you can help. It could make all the difference in getting this book into the hands of those who will carry on from all of us if you could:

* Ask whatever libraries you are connected with — law libraries, college or university libraries, public libraries — to acquire Stepping Stones. The address of Lexington Books is:

Lexington Books

4501 Forbes Boulevard

Suite 200

Lanham MD 20706, www.lexingtonbooks.com.

There is a customer service number if desired: 800-462-6420.

* If you are told that the library would purchase a paperback edition but cannot afford an expensive hardback copy at this time, we hope you will write to Lexington Books and tell them that.

Let’s look at the bright side. If your library orders a copy, you can read the durned book for free. And if enough libraries order copies it will hopefully trigger paperback production, and together we can pass on to our successors what one Zapatista has called the hope of creating “another everything.”

With thanks, love, and comradeship,

Staughton Lynd for S&A