In my previous post, I listed five discoveries and inventions from research presentations I encountered in 2015. For the remaining five presentations I cover in this post, I focus on the speakers who provided me with inspiration for communicating and writing about science topics. These speakers include a museum curator, public speaking professional, book author on engineering materials, researcher on atmospheric aerosols, and a game writer.

1

1

Ceiling-high black cabinet doors line the aisles of the Beaty Biodiversity Museum. Visitors are peering in through glass windows to see beautifully mounted specimens.

The next aisle down, one of the the black cabinet doors are open with a museum staff standing by it halfway up a ladder. He shuffles through furry animal specimens where squirrels and chipmunks are lined up belly down in perfect rows, showing off their stripes and long tails. Many visitors are surprised to see that what they see in the displays are only part of the two million specimens housed at this museum and the Biodiversity Research Centre.

Each specimen is a piece frozen in time and thus also a gateway to stories that make the animals come alive. Someone who seems to have no end to such stories is Chris Stinson, Assistant Curator of the Beaty Museum’s tetrapod collection. He is a walking encyclopedia of head-turning facts. Follow him through the rodents collection to see a Giant Flying Squirrel with a body as long as your forearm, smaller flying squirrels with the softest fur you can imagine, and pocket gophers with cheeks twice as wide as their face — Chris would be offering fun tidbits and commentary to give character to each type of animal, leaving you curious to delve into more.

2

You’re standing in front of a microphone and a huge audience. You have a great project idea and you know your research, but you’re unsure whether you’re going to tell that funny joke right, and whether you’d manage to convince people to like you and your idea.

It takes skill and practice to make a convincing and memorable talk. In a recent full day public speaking workshop, Ivan Waniz Ruiz took a group of 15 graduate students through ways to rethink the structure, language, and visuals used in presentations. Many students who were told to explain their research topic started sounding as if they were reciting their thesis title, and this rarely resonated with those outside their field. By the end of the workshop, however, the student speakers were engaging the entire class full of students who had no background in the presentation topic.

Ivan trained students to analyze people’s body language the way police interrogators would analyze a criminal’s lie or lack of confidence. By applying brain hacking tips to public speaking and practicing over and over again, presenters began to notice their own body language and use that to achieve a confident look to grab their audience’s attention and leave a lasting impression.

Ivan does what he preaches–in many past talks, I relied on notes I scribbled to remember what was said, but with Ivan, the take home messages for the students in this workshop have stayed in my head even months afterwards.

3

It was like going in to read a book for fun and coming out feeling incredibly smart and educated.

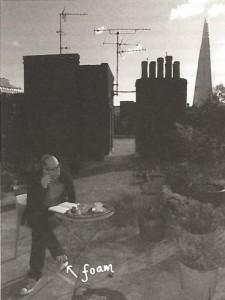

In the book Stuff Matters, a single, seemingly serene and plain photo of author Mark Miodownik sitting on the rooftop garden is the basis of his book on the great material inventions in our world. Each chapter picks up an item captured in the picture – steel, paper, concrete, chocolate, foam, plastic, glass, graphite, porcelain, and an implant.

In the very first chapter of the book, a knife stabbing incident throws you into a story of Mark’s fascination with steel, and in another chapter, his creativity flows in explaining plastic through a five-act play script. A dictionary or manual could tell you what each material is and maybe what it is made from, and an encyclopedia may tell you the history. But authors with creative writing like Mark Miodownik shows that truly everything around you has a story to tell.

4

Mechanical engineering professor Dr. Steve Rogak faced a mixed audience as he began his seminar talk.

The talk entitled “The Structure of Aerosol Nanoparticles” was of interest not only to his fellow mechanical engineers but also to students and faculty in chemistry, medicine, geography, and resource management. We are surrounded by tiny particles floating in the air which we call atmospheric aerosols, and researchers from various fields study how those aerosols – in the form of smog, engine exhaust, pollen, SO2, and others – affect our climate and health.

A talk full of jargon could have easily lost all the non-engineers, but Steve’s careful language, pace through tables and figures, and strong transitions walked the audience through the stories of his research on the structure of soot particles, which are typically emitted as a product of incomplete engine combustion. By the end of the talk, a non-expert audience like myself was able to appreciate the novel insight on proposing a new model for soot formation and structure.

As demonstrated in this seminar, when a topic like climate change has to be tackled with an understanding of chemical and physical reactions, geographical transport of air and clouds around the globe, health effects, and engineering that help mitigate emissions, many researchers in this field will have to learn how to speak to an interdisciplinary audience.

5

Each video game has its own world, set of characters, and narrative that takes you through a story. In the game making industry, all these elements start from a concept developed by a writer.

Take characters: someone telling you to draw “a male character wearing a hooded coat and weapons” likely won’t inspire much creativity, whereas a writer elaborating a concept of “an 18th century pirate in the Caribbean islands who disguises himself as a rogue assassin, using his pistol and dual blades to navigate the islands and fight his way through to an assassin’s guild,” may inspire a character with a hooded coat and weapons, but with a much richer backstory.

Writers develop the backstory, the colors of the world and characters, the features, the clothes, the behaviors, the voice and attitude–everything required to paint a picture in the minds of collaborating concept artists, modelers, animators, sound techs, and directors. Game writer Sean Smillie, in a recent talk at the launch of the Game Academy at UBC, showed how to approach writing from this creative perspective, from a writer’s role to how writers can use the power of their words to communicate ideas that materialize into a visual game.