You will be able to see a recording of this lecture in about a week’s time, on the Arts One Open site, under “lectures and podcasts” (if I remember, I’ll link to it here when it’s ready…but I might forget).

And here are the slides from Slideshare (you can download them from there if you want; just click on the link below the embedded slides)

Where I got to in the lecture was a discussion of how, for Nietzsche, we deny life through aiming for some other, “true” world as opposed to an “apparent” one, and we were talking about what Plato says in this regard in Republic and also in Phaedo. So we were at the “Nietzsche and Plato” slides.

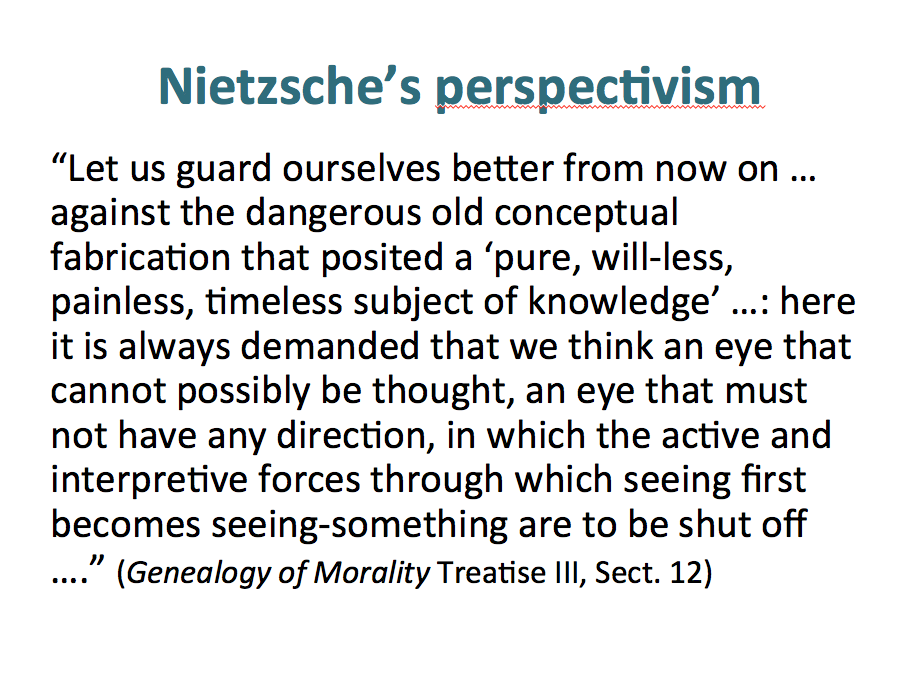

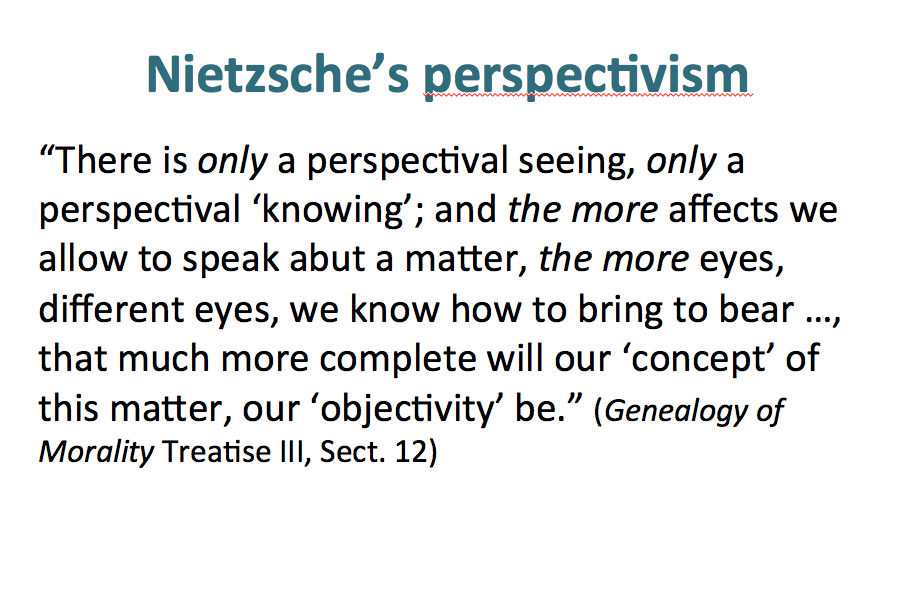

How is trying to get rid of our perspectives and aiming for some unchanging, objective truth a kind of hostility to life? It’s because it asks us to do what we cannot, in our actual lives, do; it asks us to aim for a world that is better, but that could only be reached if we are not the sorts of beings we actually are.

When we finished, I was working through what I think Nietzsche takes our “sickness” to be: caused by hostility to the instincts of life, leading to self-hatred for the passions and instincts we have, such as the will to power, that are considered through religion and morality be “bad.” We end up bearing “ill will” towards ourselves, “full of hate against the impulses to live…”, and thus “sick, wretched” (Those Who Improve Humanity, Sect. 2, p. 39).

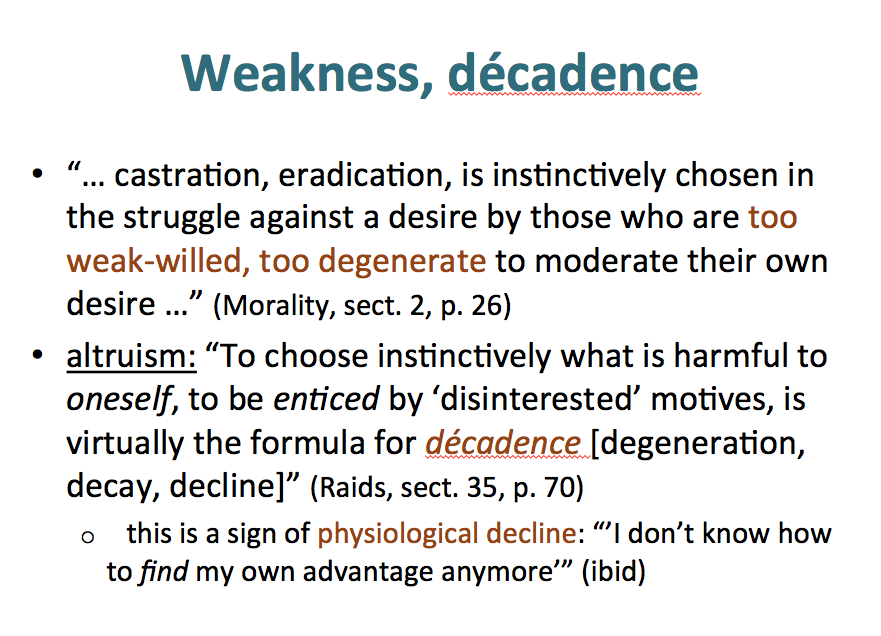

But Nietzsche also asks why we ended up with moralities and religions that make us sick. Why do we try to eliminate instincts that are after all part of and crucial to life?

Because we have no choice–this is the only morality that makes sense for those who are too weak to control our instincts and passions; we have to denigrate them, condemn them, try to get rid of them.

On the first slide: We have to try to eliminate our ‘negative’ instincts and passions because we are not able to control them. We have altruism as a moral value in part because we don’t know how to act for our own advantage, or we’re not able to. The second point on the second slide suggests that we need to be kind and considerate to each other because we recognize how weak and tender we all are, and this makes the most sense for us.

On p. 73 (Raids, sect. 37), N has another useful quote about altruistic, considerate moral values:

“The amputation of our hostile, untrustworthy instincts—and that is what our ‘progress’ comes down to—is just one of the consequences of the general amputation of vitality: it costs a hundred times more trouble and care to preserve such a dependent and late existence. So people help each other out, so each is the patient to some degree, and each is the nurse. That is then called ‘virtue’—among people who still knew a different sort of life, fuller, more extravagant, more overflowing, it would have been called something else, ‘cowardice’ maybe, ‘pitifulness,’ ‘old ladies’ morality’ ….”

I put Thrasymachus at the bottom of the second slide because the view that we have a morality of consideration, kindness, mutual help, altruism due to weakness and need of help reminds me of what Thrasymachus says in Plato’s Republic about how those who are strong enough to do what seems “unjust” according to traditional morality won’t think that such injustice is a problem. It’s only those who can’t do that and get away with it who will praise the traditional view of justice.

This idea becomes quite clear in Glaucon’s restatement of Thrasymachus’ view near the beginning of Book II of Republic. Glaucon says that those who are unable to commit injustice with impunity or avoid suffering injustice from others agree amongst themselves not to commit injustice against each other. People value justice, Glaucon says (but he’s just restating the Thrasymachean view), “not as a good but because they are to weak to do injustice with impunity. Someone who has the power to do this, however,… wouldn’t make an agreement with anyone not to do injustice in order not to suffer it. For him that would be madness” (359a).

The Problem of Socrates

After this discussion of anti-natural morality and how we have come to it because we are weak, the section on “The Problem of Socrates” makes more sense, I think.

My enduring question in this section is: what is the “problem” about Socrates, actually?

Is the problem that he himself is a problem, that there is something wrong with him? That’s surely part of it–Nietzsche is clear that Socrates belongs to those who judge life to be worthless (Problem, Sect. 1, p. 12). But one might still ask: in what way could we say Socrates judged life worthless?

Is the problem that he himself is a problem, that there is something wrong with him? That’s surely part of it–Nietzsche is clear that Socrates belongs to those who judge life to be worthless (Problem, Sect. 1, p. 12). But one might still ask: in what way could we say Socrates judged life worthless?

- If we take the Socrates here to be referring to the Socrates in Plato’s Republic, then he could be said to judge life worthless in the same way as I’ve said above that Plato does.

- If we take him to be the philosopher who engaged in what is now called the “Socratic method,” who went around showing people in Athens that they do not know what they think they know, by asking continual questions until the person themselves is forced to admit what is wrong with their view…then…is this hostile to life?

- Nietzsche suggests that Socrates’ hostility to life is in his hyper-rationalism, the demand that one give reasons for every one of one’s beliefs, values, actions, which this version of Socrates certainly could be said to have done.

- Perhaps: always having to justify oneself with reasons, with arguments, rather than acting out of instincts or passions…somehow hostile to life?

- The Socrates of Republic, certainly, emphasizes reason above all else, the control of the passions through reason as their natural ruler.

But there’s another aspect to the “problem of Socrates” that Nietzsche points to in this section: N asks how it was that he got himself listened to, how it was that people took him seriously (Problem, Sect. 5, p. 14). What did it take for the Socratic view of life, his hyper-rationalism, to become something that made sense? Of course, it didn’t make sense to all right away; Athens did put him to death after all. But his legacy lived on through Plato and many other Greek philosophers.

Nietzsche’s answer: Socrates provided a remedy that was a last resort for the Greeks, for those who were already not strong enough to control their passions and instincts: Those who cannot control their drives in any other way turn to the cure of Socrates (and Plato): attempting to rule them with reason, to conquer them, even (as noted above in the quotes from Phaedo), to eliminate them and the body as much as possible.

Those who cannot control their drives in any other way turn to the cure of Socrates (and Plato): attempting to rule them with reason, to conquer them, even (as noted above in the quotes from Phaedo), to eliminate them and the body as much as possible.

Why was this the case at the time? Nietzsche doesn’t explain clearly in Twilight. He just says that “the instincts were turning against each other” (Problem, Sect. 9, p. 16).

To me, this rings a bell (again!) with what he says in Genealogy of Morality (Treatise II, Sect. 16), that when we start to live in societies, we have to start to moderate our “darker” drives, our will to power, and can’t vent it on other members of our societies. Nietzsche refers to this idea in Twilight in What I Owe to the Ancients, Sect. 3: the ancient Greeks, he says there, raised their institutions as “security measures” against their “strongest instinct, the will to power,” “in order to make themselves safe in the face of each other’s inner explosives.” They could and did still vent it against outsiders: “The immense internal tension then discharged itself in frightening and ruthless external hostility: the city-states ripped each other to shreds so that the citizens might, each of them attain peace with themselves” (What I Owe, Sect. 3, p. 88).

So long as they have an expression for their will to power outwards, then it is less likely to be discharged inwards, against themselves, against their own instincts for power. But perhaps, as the older Greek pleasure in conquering, attacking, violence (Nietzsche suggests the world of Homer expressed this well) became reduced, then the instincts for power started turning inwards, and the instincts of the ancient Greeks then, as Nietzsche says, began to turn against each other. This is a speculation, though; I’m not sure it’s what he means.

Socrates, then, provided a way to deal with the instincts attacking each other, for those who had no other means of solving this problem: let’s make a tyrant out of reason to help control these instincts and keep them from tearing us apart.

“The fanaticism with which all Greek speculation throws itself at rationality betrays a situation of emergency: they were in danger, they had to make this choice: either to be destroyed or–to be absurdly rational …” (Problem, Sect. 10, p. 16)

But Socrates as a would-be healer is also a poisoner, as it were:

And this is because Socrates’ cure, like the efforts to condemn or eliminate the instincts and passions, also works to denigrate life. Whereas Socrates (and Plato) thought that Reason = Virtue = Happiness (think about how that’s the case for Plato), Nietzsche argues that this was “not at all a way back to ‘virtue,’ to ‘health,’ to happiness …” (Problem, Sect. 11, p. 17).

And this is because Socrates’ cure, like the efforts to condemn or eliminate the instincts and passions, also works to denigrate life. Whereas Socrates (and Plato) thought that Reason = Virtue = Happiness (think about how that’s the case for Plato), Nietzsche argues that this was “not at all a way back to ‘virtue,’ to ‘health,’ to happiness …” (Problem, Sect. 11, p. 17).

But in one of Nietzsche’s characteristic twists (I have found that often, even when Nietzsche seems to be “against” something, he still shows that it has some value), he also suggests that Socrates was nevertheless a saviour in some, albeit perhaps small, sense.

I’m getting this, as you can tell, mostly from the Genealogy of Morality. There, he says that ideals such as religion, morality, the belief in some absolute “truth” that would take us away from this work and this life, nevertheless have value in that they are a means for us to keep living. Such ideals, Nietzsche says in GM, spring from “the protecting and healing instincts of a degenerating life that seeks with every means to hold its ground and is fighting for existence” (Treatise III, Sect. 13). What seems to be a negation of life in cures such as that by Socrates, is actually one of “the very great conserving and yes-creating forces of life” (Ibid).

I’m getting this, as you can tell, mostly from the Genealogy of Morality. There, he says that ideals such as religion, morality, the belief in some absolute “truth” that would take us away from this work and this life, nevertheless have value in that they are a means for us to keep living. Such ideals, Nietzsche says in GM, spring from “the protecting and healing instincts of a degenerating life that seeks with every means to hold its ground and is fighting for existence” (Treatise III, Sect. 13). What seems to be a negation of life in cures such as that by Socrates, is actually one of “the very great conserving and yes-creating forces of life” (Ibid).

They key here is that such “cures” at least create a meaning for us, for the suffering involved in life: “Man, the bravest animal and the one most accustomed to suffering, does not negate suffering in itself; he wants it, he even seeks it out, provided one shows him a meaning for it, a to-this-end of suffering. The meaninglessness of suffering, not the suffering itself, was the curse that thus far lay stretched out over humanity …” (GM Treatise III, Sect. 28). And morality, religion, Socratic-Platonic hyper-rationality, and perhaps even Rousseau provide a meaning, a reason for it that makes sense of it.

This is how I make sense of the Epigram from Twilight noted at the bottom of the above slide. What we most need is a “why,” and then we can live with nearly any “how” in life. We don’t need to aim for happiness; suffering will be acceptable with the “why.” (N’s remark about only the English aiming for suffering is perhaps pointing to the English utilitarian philosophers, such as Bentham and Mill, who argue that everything we do is because we are aiming towards what we think will bring us happiness.)

Nietzsche and Socrates

At the end of the lecture I come back to the beginning, to the mirror image at the beginning, where I said that we might consider Nietzsche to be seeing something of Rousseau and Socrates in himself (or at least, we might see them in him).

How might we think of Nietzsche as “Socratic” in some sense? Here I’m thinking of the Socrates of the “Socratic method,” the “gadfly” I mentioned earlier in the lecture, the one who continually shows people that they do not know what they think they know.

On this slide are some aspects of Socrates that I think one might see in Nietzsche. Do you agree?

Might we think of Nietzsche, too, as some kind of doctor as Socrates was some kind of doctor, as aiming to help cure us from a sickness? The two authors I cited on a slide towards the beginning of the lecture, about a “therapeutic” reading of Nietzsche, think so.

The Hammer Speaks

I address this issue in the last section of the lecture, called “The Hammer Speaks,” referring of course to the very last section of the text (which I am both fascinated and yet still puzzled by).

Does Nietzsche offer any sort of “alternative” to the sickness we are suffering from, any way to act differently? Perhaps in his continual references to saying “yes,” to affirming life:

See the sections and pages listed above for examples of when he talks about such yes-saying.

See the sections and pages listed above for examples of when he talks about such yes-saying.

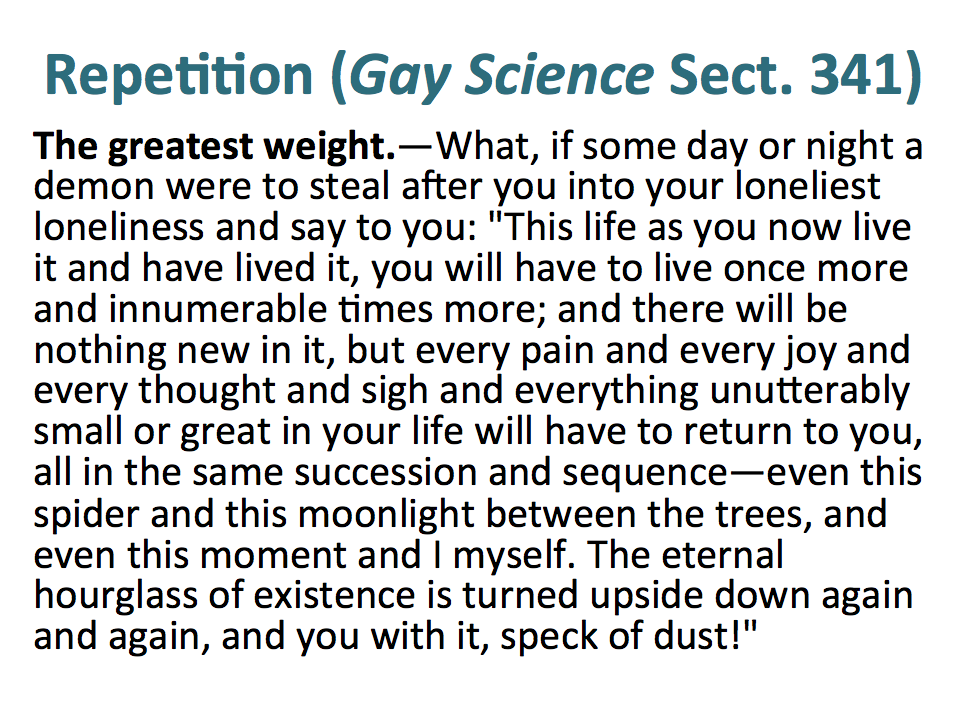

What, though, might this sort of life look like? For that, I turn to the last line of the text before the section on “The Hammer Speaks,” where Nietzsche calls himself “the teacher of the eternal recurrence” (What I Owe, Sect. 5, p. 91). The “eternal recurrence” is a contested concept in Nietzsche scholarship, as there are several things it could mean. One thing it could mean is encompassed in this quote from the Gay Science by Nietzsche:

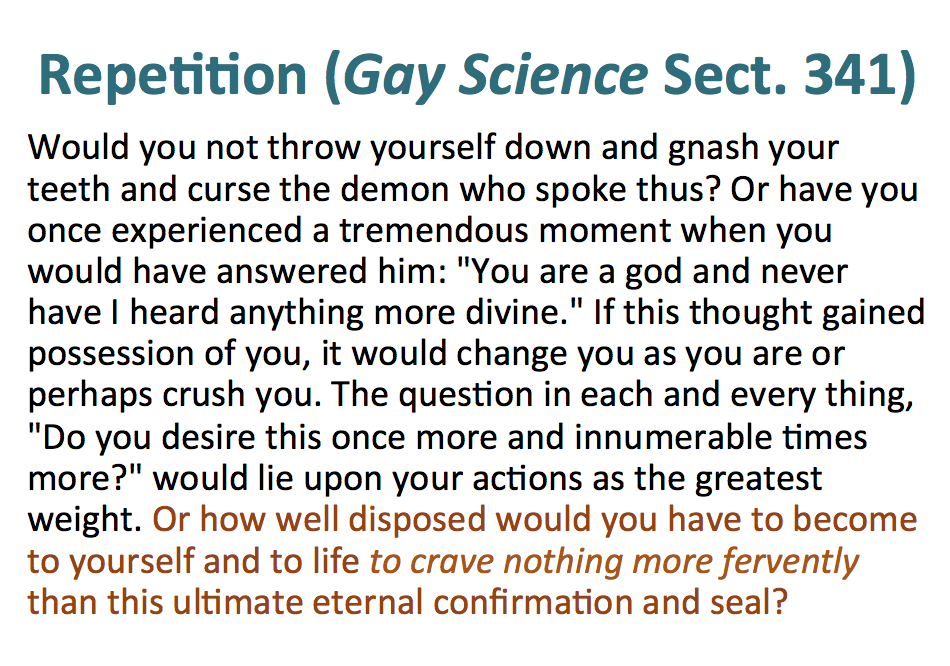

One interpretation of the “eternal recurrence” is as a thought experiment to explain what it might mean to actually say “yes” to life in a deep way, and whether you could do this. Could you will that the exact same things happen to you, over and over, forever? Remember, the demon comes to you in your “loneliest loneliness,” not when you’re feeling good about your life.

One interpretation of the “eternal recurrence” is as a thought experiment to explain what it might mean to actually say “yes” to life in a deep way, and whether you could do this. Could you will that the exact same things happen to you, over and over, forever? Remember, the demon comes to you in your “loneliest loneliness,” not when you’re feeling good about your life.

Getting back to our theme (which I think is expressed in the lecture in large part through Nietzsche showing us our past and present, revealing to us our “idols” but in a way that makes them sound different than we usually “hear” them, this is repetition at its extreme.

Nietzsche also connects this kind of deep affirmation of even the most terrible things in life, and the eternal recurrence, to Dionysus. This is, I think, a reference to his first published work, The Birth of Tragedy, in which he speaks of Dionysus as a representation, in Greek tragedy, of forces of life and nature that are destructive, chaotic, amoral, absurd and horrible (opposing this to Apollo as a representation of the ways in which Greek art, and also tragedy, aim for order, clarity, proportion, harmony, and individuation–whereas the Dionysian element destroys individuation, individual identity, unifies us with the whole). The Dionysian rites, Nietzsche states in Twilight, also emphasize sexuality, reproduction, t

he pain required for new creations and new births. In that sense, perhaps, being Dionysian may refer to being able to face the destructive, chaotic, horrible aspects of life, to celebrate sexuality rather than denigrate it.

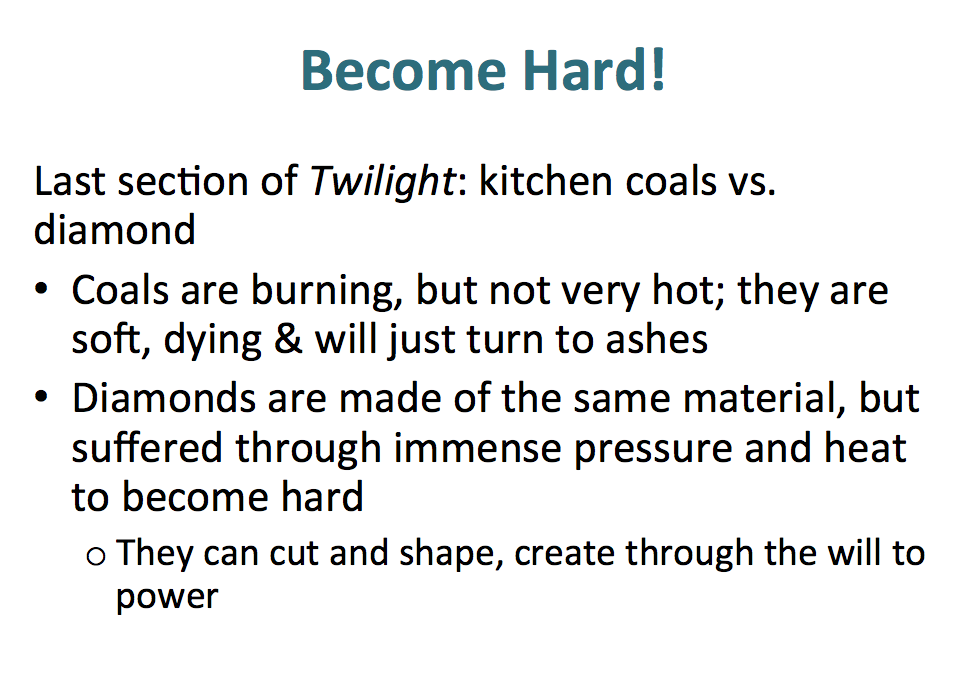

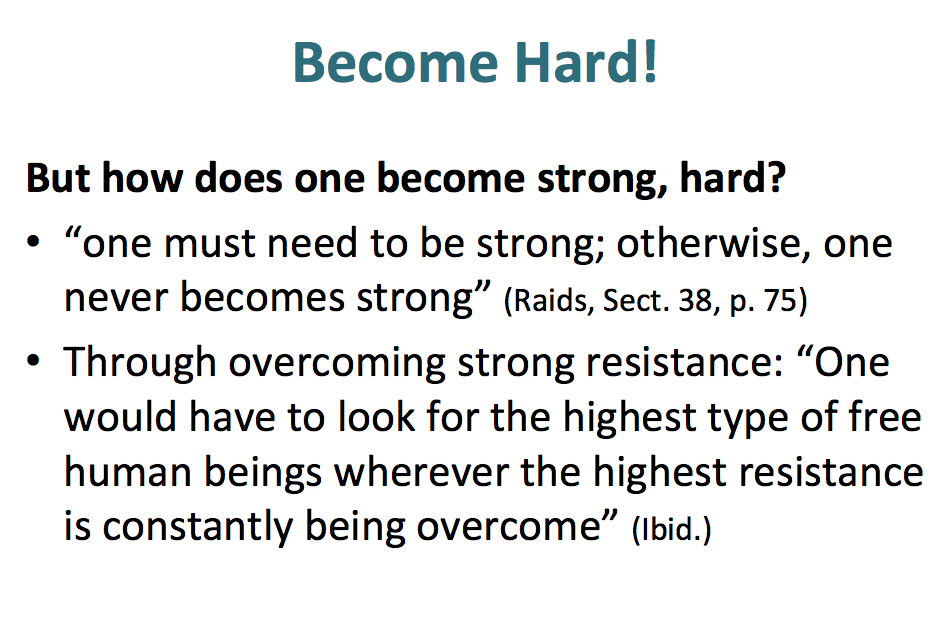

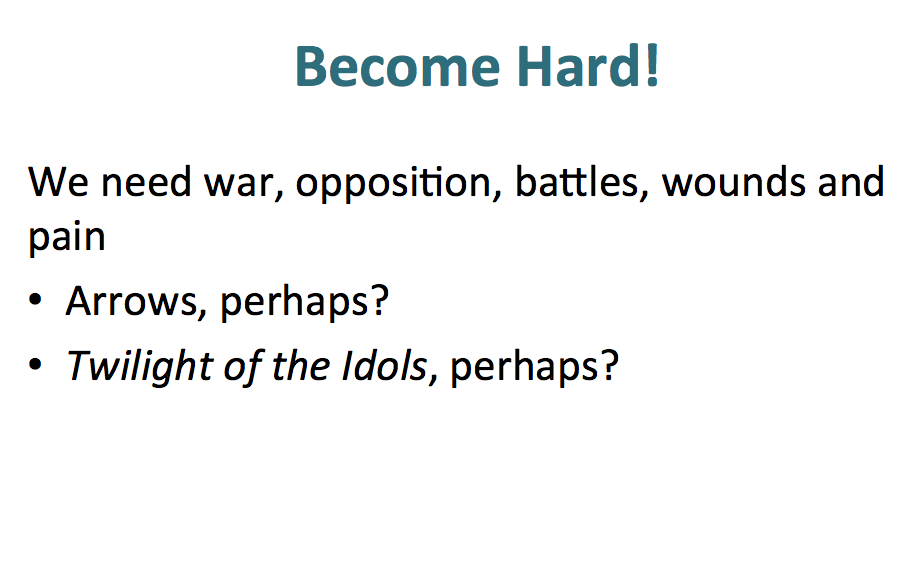

The last three slides attempt to give a reading of the last section of the text, where the “hammer” speaks. The idea here is to consider how it is that one might become Dionysian, someone who says “yes.”

I’ll leave these last slides here without comment, as I hope they’re fairly self-explanatory. Feel free to ask me any questions about them (or anything else), below!