For the Creative Commons Certificate course I’m taking right now, our discussion question this week was [there is a publicly viewable doc with all the discussion questions and assignments for the course]:

Both the NonCommercial restriction of the Creative Commons licenses and the ShareAlike condition of the licenses are poorly understood by novice CC users – and even some long-time users. How would explain the issues with NC to a person choosing to use a CC license for the first time? How would you explain the way SA works to a person choosing to use a CC license for the first time?

I wrote a quite long reply, which I’m copying here for possible future reference!

I started thinking about the issues and questions with these two elements of CC licenses about 5 years ago, when I was really starting to dig into OER and open licenses. I was taking a course from the Open University on open education, and we were asked to choose a CC license for the works we create. I decided on CC BY and explained why I hadn’t chosen NC in one blog post, and why not SA in another blog post. Re-reading these, I find the thoughts there still resonate with me. But asking people new to these ideas to read through two long posts would be too much!

To explain NC and SA to someone new, and some of the possible issues with one or both, I’d say something like the following. I’m going to assume I’m speaking to either a post-secondary instructor, student, or staff member, since that’s the context in which I am most often speaking about Creative Commons.

NonCommercial

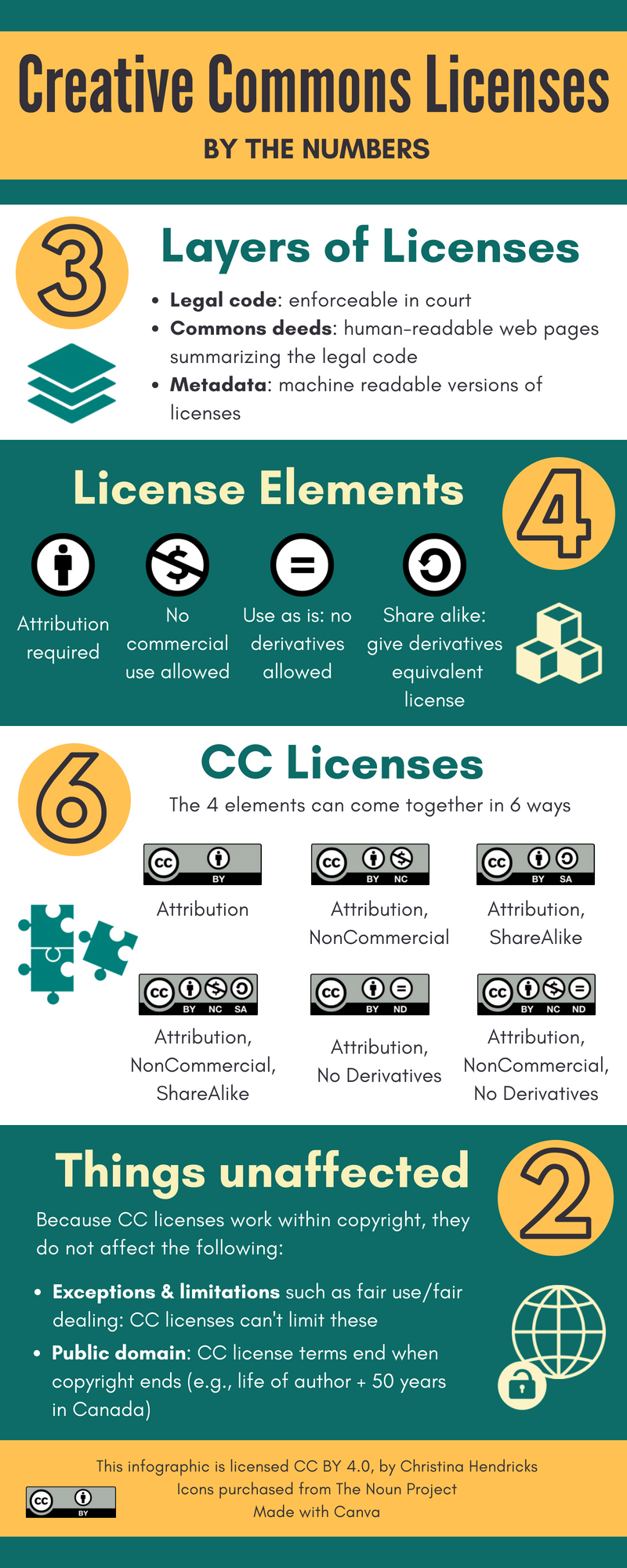

Say you find a resource that has a CC BY-NC license. This means that it cannot be used for a “commercial” purpose. According to the terms of this license:

“NonCommercial means not primarily intended for or directed towards commercial advantage or monetary compensation.”

What’s important here is the use of the resource, not who or what organization is using it. Regardless of whether it’s a teacher, a student, someone in a government, or a for-profit corporation, the question is the same: is the intended use primarily for monetary compensation? If so, then the resource can’t be used. If not, then it can be used, even by the corporation.

Lack of clarity

Note that whether something counts as a commercial use isn’t always easy to determine, including in an educational context. Just because we work or study at a university doesn’t mean we are exempted from the NC restriction. This means that if an instructor wanted to assign a resource licensed CC BY-NC for a class, and put it into a course pack that the bookstore copied and charged students for, this could go against the NC license: if there is a charge beyond just cost recovery for copying (e.g., a bookstore markup), then this would be a violation of the NC part of the license.

There are other difficult cases in the educational context, where it’s unclear if a use would count as commercial or not. What if a post-secondary institution created a MOOC that was available free of charge but students could sign up for a certificate, in which case they’d have to pay? Can the MOOC use content licensed CC BY-NC? I have sometimes gotten honoraria to give presentations and workshops at various institutions; would it be a violation if I used content licensed CC BY-NC in my slides? We could probably find answers to these questions, but the point I’m making is that determining whether a use is primarily for “commercial advantage” or “monetary compensation” is sometimes murky, and even if we find answers to some test cases, others will pop up.

The result of this is that material licensed with NC simply may be used less often by well-meaning, conscientious people who legitimately wonder about whether their particular use would violate the license. (Of course, neither NC nor all rights reserved will stop the non-well-meaning people!).

What’s your goal?

When choosing a license for one’s own work, one should consider the what one’s goals are. If the goal is to share the work so that it is used widely, then perhaps NC isn’t the best. As one of the other students in this course has pointed out in the discussion board, if someone could take what you’ve created and make it even better by making an interactive resource (for example), but they need to make some money in order to pay for the system and labour their using to do it, doesn’t it seem to make sense that they could be compensated for that? And the resource gets even more used than it might otherwise. So if widespread use is one’s main goal, others using the work and adding more to it, even if they charge some money, still fulfills that goal.

Also in the discussion board for this course, someone pointed to a 2016 blog post by David Wiley called “Advocating for CC BY” that raises an important point I hadn’t considered before: all of the CC licenses require attribution (CC0 does not, but it’s not a license), and the attribution must include a link to the original work plus a notice of the CC license. You can also specify how you want to be attributed, and in that specification you could require that people say that “this resource is available for free at … [give a website]”. This could serve a similar purpose to NC: it could mean that those who want to make a profit just off the resource itself couldn’t do so because they’d have to say the resource is free elsewhere. Of course, if they’re adding value to the resource somehow people might still be willing to pay for that, but again, if they’re adding value then it seems legitimate for them to ask people to pay for that value. And if people only want the resource then they can get it for free at the download link.

ShareAlike

If one is still worried about others possibly using their resources for free and then adding something to them to make money, they could consider a “share alike” license, such as CC BY-SA. This requires that if anyone creates a derivative using a work licensed with an SA element, the new work has to be licensed with the same license (or an equivalent license) as the original. This is a good license to use if one’s goal is not only to have one’s work widely used, but also if one wants to ensure that derivative, downstream works continue to be able to be used and adapted without cost. If one used CC BY for one’s work then it could be enclosed by someone else into another work that is put behind a paywall and has all rights reserved, and so is neither easily accessible nor able to be revised without express permission.

Harder to make money (but not impossible)

Let’s say one created a resource, licensed it CC BY-SA, and someone else took that resource and made it into an interactive one, to stick with the same example as above. The new work must also be licensed CC BY-SA. In this case, then, it’s harder for the second person to charge money for the work. They could do so, but someone else could just come along, download it, and put it up somewhere else with the same license and legally that would be fine.

So SA can make it harder to make money from a derivative work. But SA is not the same as NC, and one can make money by using works licensed CC BY-SA. The share alike clause only applies if one makes a derivative. But let’s say one uses an image licensed CC BY-SA in an online course that people have to pay to register for. If the image is used as is, not altered at all, then this is legally permissible (I think! Please someone correct me if I’m wrong!). Similarly, if you create a video and license it CC BY-SA, then someone else could use the video in its entirety, intact, in such an online course that costs money to take.

Remix restrictions

SA is not without issues, though; such works are less easily remixed with other works than, say, those with CC BY licenses. One has to worry more about license compatibility when putting together two or more works that have either NC or SA restrictions, as explained on this license compatibility chart.

What’s your goal? (redux)

So again, if wide usability is one’s goal, then perhaps simply CC BY (or CC0) is the best bet for one’s own work.

If one’s overriding concern is to share work free of cost and ensure that others can’t use it in a way that makes them money, then NC is probably better than SA. But it will likely be less widely used, as noted above, because of the lack of clarity (SA is clearer in that one can easily fulfill it by using the same CC license on a derivative as on the original work).

If one’s main goal is to share work and ensure that later derivatives continue to be available for free and have derivatives made from them, then CC BY-SA is the better license.