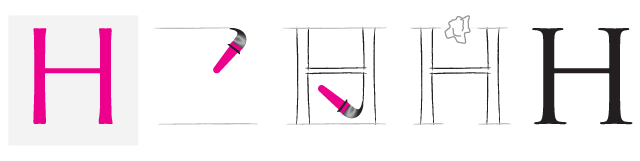

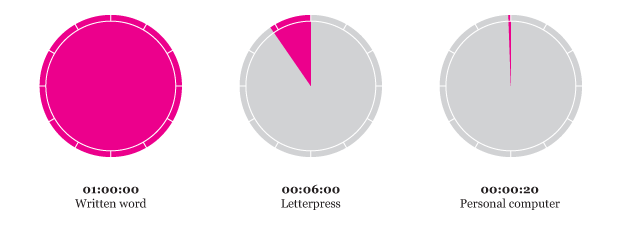

The invention and popularization of the personal computer almost 30 years ago opened the door to the auto-edition era and therefore, to the informal knowledge and use of typography. But typography as a concept has existed since Gutenberg’s invention of the lead movable types letterpress (Winship, 2005) about 550 years ago, an important event in the long history of written word, history that has nearly 5300 years (Fischer, 2004).

Along this history, both chirographic (“[…] pertaining to, or in handwriting” [Oxford,English Dictionary]) and typographic signs have been shaped by several factors that can be summarized in to two main aspects: the cultural and the technological one. For the purposes of this document, in the cultural one, I will subsume all of the factors that are not directly related to the writing instrument and the support (surface of writing) that are considered technological. In this context, technology will be understood as the process of “[…] dealing with the mechanical arts and applied sciences […]” (Oxford,English Dictionary). In the same way we can now separate the components of a digital device in software and hardware.

To track the influence of technology in the chiro/typographic sign, it is necessary to define a limited and easily identifiable set of formal characteristics. For this document, these characteristics will be:

Contrast: The difference between the thin and thick traces of a sign, being high when there is a notable difference, and low when the difference is barely noticeable. (Bringhurst, 2004)

Contrast: The difference between the thin and thick traces of a sign, being high when there is a notable difference, and low when the difference is barely noticeable. (Bringhurst, 2004)

Features: Those elements that add the basic strokes of a letter: mainly serifs and terminals. (Bringhurst, 2004)

Features: Those elements that add the basic strokes of a letter: mainly serifs and terminals. (Bringhurst, 2004)

x-height and width: The former is the height of the lowercase “x” measured from the baseline. This responds to the fact the the x is the only lowercase letter with relative evenness on its top and bottom. (Bringhurst, 2004) The latter stands for the horizontal proportion of the whole sign.

x-height and width: The former is the height of the lowercase “x” measured from the baseline. This responds to the fact the the x is the only lowercase letter with relative evenness on its top and bottom. (Bringhurst, 2004) The latter stands for the horizontal proportion of the whole sign.

Although it is very difficult to isolate the evolution of these characteristics in time, we can say the some of them were directly modified by technology since before the invention of the Gutenberg’s letterpress, like contrast or the apparition of the serif. Some others, like the x-height and width were modified since the invention of letterpress, which might be understood as very conscious efforts of adaptation for specific purposes that will be addressed later.

Contrast

Basically, contrast is per se a result of technology, every chiseled tip shaped tool will potentially develop a contrasted trace; in fact, presumably the first writing was made with “ink with a chiseled reed pen” (Fischer, 2004, p. 47).

The most popular of these instruments was the quill. Some authors place its use along its invention in the first century A.D. (Smith, 1901), to the invention of the first metal pen in the second half of the XVIII century; some others, between the 6th century and the first half of the XIX century (Nickell, 2002). Whatever the correct dates are, during all this time, contrast was one of the few stylistic features that could be controlled if not by the writer, by the crafter of the quill, by making the tip wider or narrower.

Serif

According to Edward Catich (1991) the serif was mostly an accident, an error immediately legitimized for being culturally appealing. Apparently, this mistake took place during the monumental roman letters rock carving process. First, letters were traced with brush on the rock by scribes. Then, these letter had to be chiseled by illiterate workers known as masons. As the latter ones did not really know the letters, the limits of each letter were indicated with a line that the carvers mistaken for a part of the letter, originating the serif.

It is also possible to infer that this new style of scripting, being a reminiscence of the roman column, was quickly accepted as a roman identity element, but there is no documented evidence to support this inference.

Eventually, serif was accepted and assumed as an integral part of the letter structure, being reproduced in formal hand written documents and later, by the letterpress. The sans-seriffed style did not reappear until the second half of the XVIII century, but it only caused real interest since the XIX century. (Bringhurst, 2004)

The letterpress

Gutenberg’s invention can be considered, by itself, a major technological shift in the history of writing. However, it did not influence the shape of the signs immediately, because early printers tried to imitate handwriting as much as possible (Goudy, 1940).

It was after its popularization that the new media started to manifest its own nature through typography, getting it away from calligraphy and bringing it closer to the geometric forms that characterize it during industrial revolution and modernism. Obviously, the general aspects of typography suffered changes because of this invention.

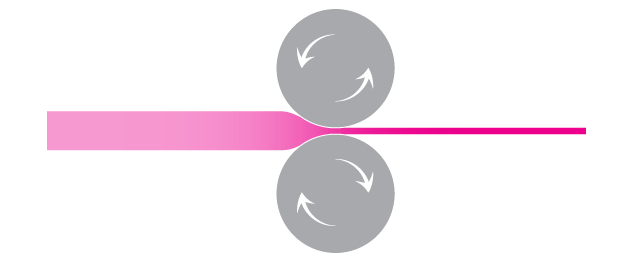

The next major shift occurred not in the printing process itself, that remained almost unchanged for the next 5 centuries, but in the quality of paper. The responsible of this transformation was John Baskerville, who, during the first half of the XVIII century, allowed the design of fonts with a higher contrast and sharper lines by inventing a not very well known process for smoothing the surface of paper by pressing it against heavy hot cylinders (Meggs, 2011). Basically, by smoothing the printing surface, he augmented the possibility of adding detail to typography design, shaping the typographic style of the time and the following years.

X-height and width

Fitting more text in a page has been a concern since the beginning of writing. Economy, in fact, was one of the main reasons for the development of the gothic script (Gaultney, 2001). The first conscious and successful attempts to modify the design of the letters were made by Pierre Haultin, who in 1559 enlarged the x-height of a relatively small size letter, gaining amount of characters per line ⎯ what Dyson named “character density” (2004, p. 369) ⎯ without sacrificing legibility (Morison, 1997).

This technique was widely used for the design of newspapers along the XX century, and it is still being used for the design of typefaces for the same media. Economy is still an issue, but the characteristics of the printing system are an issue too.

Nowadays, newspapers are printed in a cheap, high speed printing system called rotatory printing press. The speed is directly linked to how fast the ink dries in the paper, so paper is highly porous and ink very fluid, and this characteristics can noticeably affect the integrity of the printed signs. To compensate this, typeface legibility factors are stressed, and x-height among them (Gaultney, 2001).

Condensed and compressed typographical forms as resources of economy started to be used since the XVIII century, and were eventually adopted by newspapers too. But the effects of condensation haven’t been deeply explored (Gaultney, 2001), and usually x-height is considered to be a better solution.

Conclusion

Despite these, many other little changes than can be attributed directly or indirectly to technology occured during the history of chiro/typography, but the ones chosen for this document are, according to my opinion, some of the more influencing, better documented or more noticeable.

Moreover, it is important to mention too that the digital era came along with great changes for the typographic sign, changes that even though are not being considered in this document are very relevant for the history of writing.

REFERENCES

Bringhurst, R. (2004). The elements of typographic style. Hartley & Marks, Publishers.

Catich, E. M., & Gilroy, M. W. (1991). The origin of the serif: Brush writing & roman letters. Catich Gallery, St. Ambrose University.

Dyson, M. C. (2004). How physical text layout affects reading from screen. Behaviour & Information Technology, 23(6), 377-393.

Fischer, S. R. (2004). History of writing. Reaktion Books.

Frutiger, A., & Bluhm, A. (1998). Signs and symbols: Their design and meaning. Watson-Guptill Publications.

Gaultney, V. (2001). Balancing typeface legibility and economy.

Goudy, F. W. (1940). Typologia: Studies in type design & type making, with comments on the invention of typography, the first types, legibility, and fine printing. University of California Press.

Meggs, P. B., & Purvis, A. W. (2011). Meggs’ history of graphic design. Wiley.

Nickell, J., & Hamilton, C. (2002). Pen, ink, & evidence: A study of writing and writing materials for the penman, collector, and document detective. Oak Knoll Press.

Oxford, E. D.“Chirograph, n.”. Retrieved

Oxford, E. D.“Technology, n.”. Retrieved

Smith, A. M. (1901). Printing and writing materials: Their evolution. A.M. Smith.

Tracy, W. (2003). Letters of credit: A view of type design. D.R. Godine.

Winship, G. P. (2005). Gutenberg to plantin an outline of the early history of printing. Kessinger Publishing.