Most blog posts, articles or books with a title like this would go on to describe the positive impact of peer instruction on student learning. I even write those kinds of posts, myself.

This one is different, though, because it’s not about peer instruction being worth the effort by (and for) the students. This one is about how it’s worth the effort by (and for) the instructor.

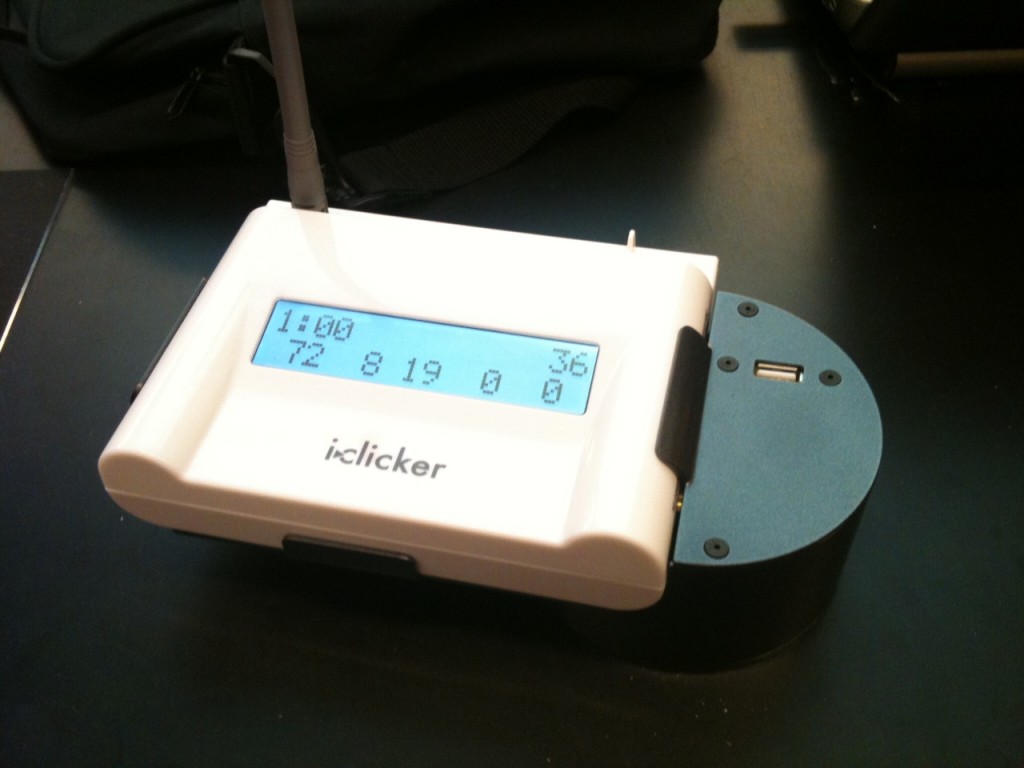

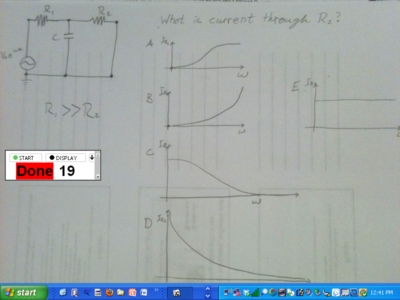

In my job with the Carl Wieman Science Education Initiative, I sometimes work closely with one instructor for an entire 4-month term, helping to transform a traditional (read, “lecture”) science classes into productive, learner-centered environments. One of the common features of these transformations is the introduction and then effective implementation of peer instruction. At UBC, we happen to use i>clickers to do facilitate this but the technology does not define the pedagogy.

Early in the transformation, my CWSEI colleagues and I have to convince the instructor that they should be using peer instruction. A common response is,

I hear that good clickers questions take soooo much time to prepare. I just don’ t have that time to spend.

So, is that true, or is it a common misconception that we need to dispel?

Here’s my honest answer: Yes, transforming your instructor-centered lectures into interactive, student-centered classes takes considerable effort. It feels just like teaching a new course using the previous instructor’s deck of ppt slides.

What about the second time you teach it, though?

A year ago, in September 2010, I was embedded in an introductory astronomy course. The instructor and I put in the effort, her a lot more than me, to transform the course. By December, we were exhausted. Today, one year later, she’s teaching the same course.

My, what a difference a year can make.

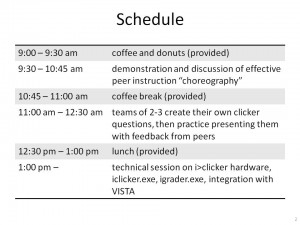

This morning I asked her to tell me about how much time she spends preparing her classes this term, compared to last year. We’re not talking about making up homework assignments or exams or answering email or debugging the course management system or… Just the time spent getting ready for class. This year she spends about 1 hour preparing for her 1-hour classes. That prep time consists of

- a lot of re-paginating last year’s ppt decks because they’re not quite in sync. Today’s Class_6 is the end of one last year’s Class_5 plus the beginning of the last year’s Class_6 so it needs a new intro, reminders, learning goals slide.

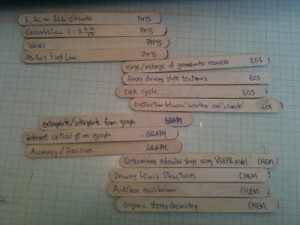

- she tweaks the peer instruction questions, perhaps based on feedback we got last time (students didn’t understand the question, no one chose a particular choice so find a better distractor, and so on). The “Astro 101” community is lucky to have a great collection of peer instruction questions at ClassAction. Many of these have options where you can select bigger, longer, faster, cooler to create isomorphic questions. It takes time to review those options and pick ones which best match the concept being covered.

- like every instructor, she looks ahead to the next couple of classes to see what needs to be emphasized to prepare the students.

“And how,” I asked, “does that compare to last year?”

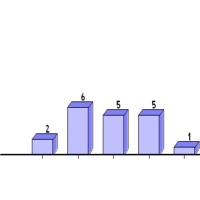

Between the two of us (I was part of the instructional team, recall) we probably spent 4-5 hours preparing each hour of class. In case you’ve lost the thread, let me repeat that:

Last year: 4-5 hours per hour in class.

This year: 1 hour.

“And do you spend those 3-4 hours working on other parts of the course?”

Nope. Those 3-4 hours per class times 3 classes per week equals about 10 hours a week are now used to do the other parts of being a professor.

Is incorporating peer instruction into classes worth the effort? Yes, absolutely. For both the students and the instructors.