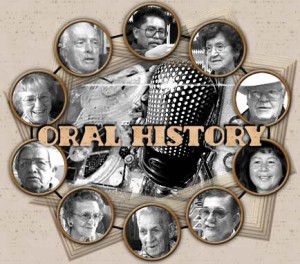

For years, the researchers painstakingly recorded and transcribed oral histories from many of the leaders of the factions caught up in the Troubles in Northern Ireland. They pledged absolute secrecy to their subjects until after their deaths.

This is not your typical and straightforward case of researchers’ data becoming embroiled in a legal battle, and I’ve no sense that I understand all the details, players, and consequences. In Secrets from Belfast: How Boston College’s oral history of the Troubles fell victim to an international murder investigation, Chronicle of Higher Ed reporter Beth McMurtrie gives a pretty full account of the matter. And CNN had a 2012 story, Secrets of the Belfast Project, and the text of a conference paper, The Belfast Project and the Boston College Subpoena Case about the initial subpoena was written by Anthony McIntyre. And, a good overview of the issues around resisting subpoena’s for research data can be found on the Institutional Review Blog.

That this was not a research project is apparent ~ it was not conducted by BC researchers, it was described as not your typical oral history, and there was no participation by BC institutional research review board. Belfast Project’s organizers were: Thomas Hachey, BC’s head of Irish programs; Ed Moloney, project director and journalist; Anthony McIntyre, project interviewer, historian, and former IRA member; and Robert O’Neill, head of the Burns Library at BC.

One imagines that BC’s motivations were complex:

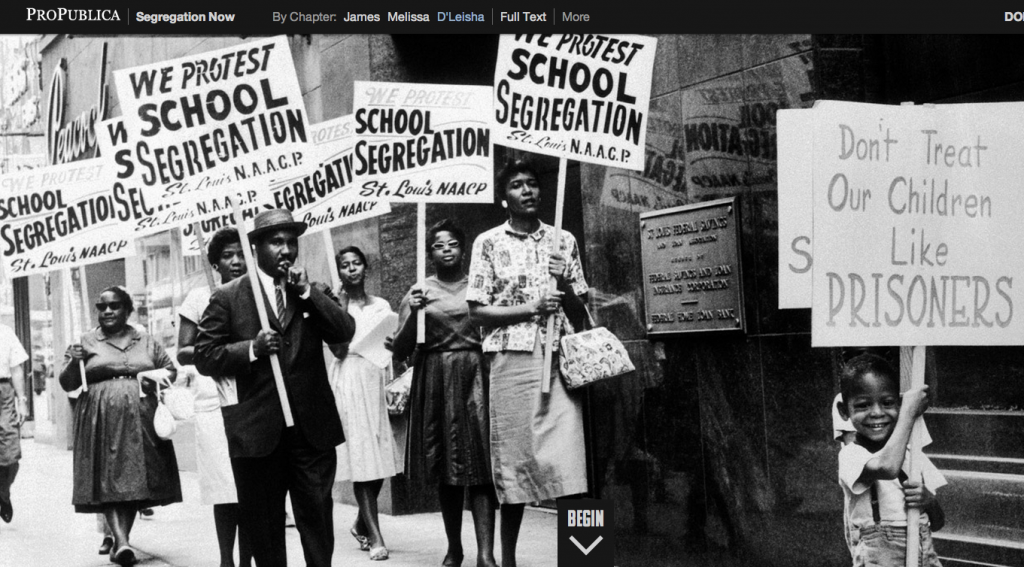

An Irish-American success story, BC has risen from a modest 19th-century college, founded to educate the children of poor Irish immigrants, into a prestigious institution with an endowment of nearly $2-billion. It has proudly maintained its connections to Ireland through its Irish collection at the Burns Library, its Irish-studies program, and its Irish Institute, which attempts to promote reconciliation in Ireland and Northern Ireland through professional-development programs.

Some have suggested that had there been IRB review and approval for the project, none of this would have happened. This is unlikely, as IRBs are relatively feeble guardians of confidentiality. And, this is a serious problem for research (oral history is certainly a prime example) where narrators, participants, and sources are necessarily named. Others have noted the chilling effect the successful subpoena will have on research on criminal, political and violent social phenomena.

Some have suggested that had there been IRB review and approval for the project, none of this would have happened. This is unlikely, as IRBs are relatively feeble guardians of confidentiality. And, this is a serious problem for research (oral history is certainly a prime example) where narrators, participants, and sources are necessarily named. Others have noted the chilling effect the successful subpoena will have on research on criminal, political and violent social phenomena.

This case is a mess and there is little reason to believe we understand all that is going on. However, researchers continue to do research and the legal and criminal battle around the Belfast Project should provide fodder for continued debate about how research can be done ethically, especially when the focus is something illegal or criminal. Just a few take aways:

- researchers should be more cautious about the promises of confidentiality they make… simply saying it isn’t much of a guarantee, but explicitly considering how and if indeed confidentiality is necessary is essential

- new strategies for protecting confidentiality are needed, so leaks to the press and police are avoided

- universities need to step up to the legal plate and defend researchers and all of the IRB hoops they ask researchers to jump through… if researchers are required by the university to promise confidentiality then the university is obligated to defend that promise

See also, my previous posts on the Luka Magnotta case in Ottawa, where the courts upheld the confidentiality of research interviews.

UPDATE: Boston College has agreed to return interview tapes and transcripts to interviewees who request them. It’s the least they can do, but the Belfast Project debacle illustrates how politics and lack of consideration for ethical issues might make very interesting research nearly impossible.

UPDATE: NBC News requested the release of the Belfast Project transcripts, and a federal court judge has ruled against that request.

Follow

Follow