We tell ourselves stories in order to live. ~ Joan Didion

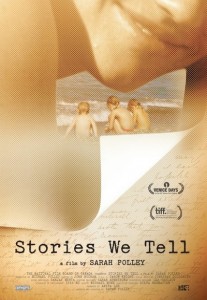

Sarah Polley’s film Stories We Tell is about her mother Diane Polley, or so it seems initially. It is much more than that though. It is an artful alternately weaving and unravelling of narratives of those who share experiences, but, of course, tell their own stories of those experiences. The story unfolds at one level as the story of Diane Polley, a notable Canadian actor (with a daughter who is now both notable actor and director), although the story is more about her personal than professional life. Polley asks each storyteller to “tell the story from the beginning” and she privileges each in the unfolding story that ultimately revolves around the family “joke” that Sarah does not look like anyone else in the family. Individual stories layer and turn back on themselves as that family story becomes a story of its own when Sarah finds out that the man she thought was her biological father is not.

Sarah Polley’s film Stories We Tell is about her mother Diane Polley, or so it seems initially. It is much more than that though. It is an artful alternately weaving and unravelling of narratives of those who share experiences, but, of course, tell their own stories of those experiences. The story unfolds at one level as the story of Diane Polley, a notable Canadian actor (with a daughter who is now both notable actor and director), although the story is more about her personal than professional life. Polley asks each storyteller to “tell the story from the beginning” and she privileges each in the unfolding story that ultimately revolves around the family “joke” that Sarah does not look like anyone else in the family. Individual stories layer and turn back on themselves as that family story becomes a story of its own when Sarah finds out that the man she thought was her biological father is not.

Interviews of siblings, friends, spouses, lovers, and children in Stories We Tell are amazingly intimate and artful illustrations of poignant in-depth interviewing based on difficult questions. The movie is family talking to each other. Everyone misses Diane, and each suffers her loss deeply since she died of cancer when Sarah Polley was 11. The answers offered aren’t simple, and Polley’s own movie narrative reveals the twists and turns in her own story, which is more what the film is about. Some reviewers have called it a love letter to her parents. There are fleeting senses from time to time that the story is told, but then it isn’t and by the time the film ends it is clear there is no end to the story. Ever.

If one were interested in exploring narrative inquiry as a research methodology, this film is about as good a place as any to begin. It illustrates the tensions of truth-telling versus storytelling. It illustrates that all stories have gaps, omissions, and contradictions and within each of those, another story is being told. It illustrates the complexity of whose story is being told. It illustrates the connections and disjunctures between subjective and inter-subjective experiences. It illustrates the role of memory and reenactment in storying life. It illustrates the role stories play in making sense of experience. It illustrates the deeply emotional meaning of stories. It illustrates the human desire to explore what might well be unknowable.

Follow

Follow