Having read a few of Orwell’s other books (Animal Farm, Down and Out in Paris and London, and Burmese Days) I’m quite familiar with his writing style, which has a very matter-of-fact way of explaining and analyzing situations. There seems to be a deep sense of pessimism and disappointment with human nature throughout his works, from his account of the conditions in the trenches along the Aragon front, his experience in poverty recounted in Down and Out, or his chilling depiction of colonialism in Burmese Days. Disillusionment seems to be a common theme; the loss of one’s ideals in the face of a reality to which they don’t conform.

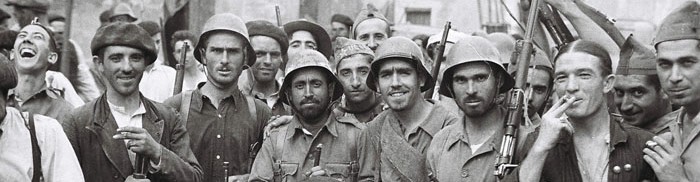

After being swept up by the revolutionary fervor that had overtaken Barcelona and joining a Marxist militia, he sees the egalitarian principles by which the war was conducted on the Republican side slowly eroded away by sectarian in-fighting and propaganda. The experience seems to have dispelled any romantic notions he may have held about communism (or at least the “official” communism promoted by the Soviets) and hardened his resolve as an opponent of totalitarianism (a role he would continue when writing Animal Farm and 1984).

Perhaps the pessimism expressed throughout Orwell’s work results from the era in which he lived, one in which war and economic hardship were prevalent for decades in a row. One can trace the formation of his political and social views throughout his books, and Homage to Catalonia could possibly be seen as a turning point in his political education. The point where rosy ideals about social equality are brought face-to-face with the tangible threat posed by fascism and Stalinism. Indeed, his account of the conflict provides us a glance into the ideological divisions and partisan conflicts that engulfed not just Spain but all of Europe at the time.

In response to the question of what type of book this is, I think it combines elements of a historical novel with those of an autobiography. Personable, anecdotal accounts of events as they happened to him, as well as an informative overview as to the larger political developments surrounding those events, combine to create a work of literature that not only draws the reader into a story of wartime struggle but is a critical account of the political climate of the time. Perhaps its difficulty in being neatly categorized reflects its strengths in providing both an entertaining account of the war while also maintaining a journalistic duty to report the facts as they were witnessed.