Hope is at best an ambivalent sentiment: it both resists and recognizes doubt. “Hope springs eternal,” but we “hope for the best and prepare for the worst.” It is also strangely passive: when we hope something happens (or that it doesn’t), we are acknowledging that it is somehow beyond our control. When we hope, we lay ourselves open to circumstance and fate. So hope is both resilient and fatalistic: hope against hope.

Something of this ambivalence can certainly be seen in André Malraux’s Spanish Civil War novel, L’espoir (translated variously as Man’s Hope or Days of Hope). On the one hand, the book tracks the first few months of the war, before factional infighting had destroyed a Revolution whose “driving force,” one of Malraux’s characters tells us, “is–hope” (37). On the other hand, even at this early stage the Republic’s weaknesses are clear and it often seems as though hope is all its adherents have, and even that is “gasping to survive, like a man who is being throttled” (44). It’s all too easy for an apparent cause for optimism to be revealed as nothing more than a “charitable lie” (93). Malraux’s characters are therefore torn between a self-defeating realism and a hope they know (not so very) deep down to be impossible and self-deluding. Hence the revolutionary spirit is described as a “Apocalypse of fraternity” (100). It embodies all the virtues of human sociability and commonality, but for that very reason it is doomed: “the apocalyptic mood clamours for everything right away. [. . . But] it’s in the very nature of an Apocalypse to have no future. . . . Even when it professes to have one” (102).

Hope alone, then, is insufficient, not least because this (Malraux suggests) is a new kind of war: “a war of mechanized equipment”; and yet the Republicans are “running it as if noble emotions were all that mattered!” (98). But Malraux doesn’t allow this question to be fully settled. Instead, his characters continuously argue (at times, bicker) about the role of technology, organization, and efficiency in determining the war’s outcome. For the intellectual, Garcia, for instance the problem is that the Revolutionaries are taking the Russian Revolution as their model, forgetting that this was not so much “the first revolution of the twentieth century” as “the last of the nineteenth. The Czarists had neither tanks nor ‘planes; the revolutionaries used barricades. [. . .] Today Spain is littered with barricades–to resist Franco’s warplanes” (99). Later he points out that, whatever bravery the disorganized Republican militias may demonstrated, “mass courage in the field [. . .] can’t stand up against ‘planes and machine guns” (176). And as for the Republicans’ ragtag airforce, endlessly waiting for Russian planes that never come (while Hitler and Mussolini ensure that Franco is endlessly supplied), as Garcia says to the airman Magnin: “I doubt if you expect to keep your Flight up to the mark on a basis of mere fraternity” (102). For Garcia, “this would be a technicians’ war” (98).

By contrast, however, other voices vouch for fraternity, courage, and hope, even in the cause of a losing side–and even, indeed, if they ensure that the cause itself is lost. The anarchist Negus, for instance, declares that “it’s courage gets things done. Cut the crap!” (171). And from a rather different perspective, Hernandez, a career army officer who refuses to join Franco’s mutiny, declares that “a world without hope is . . . suffocating. Or else, a purely physical world” (195). Speaking of the militia, who too often resemble a disorganized and ineffective rabble, he says that “if nothing in you responds to the hope that animate them, well then, go to France, there’s nothing for you to do here” (196). And to Garcia, Hernandez asks “What’s the point of a revolution if it isn’t to make men better?” and argues that it can be brought about by “the most humane element of humanity.” (180). To which Garcia responds that “Moral ‘uplift’ and magnanimity are matters for the individual, with which the revolution has no direct concern; far from it!” (183). But even Garcia concedes the dangers involved: that “a popular movement, or a revolution, or even a rebellion, can hold on to its victory only by methods directly opposed to those which gave it victory” (102). For to lose hope it to give in to cynicism, and to put one’s faith in technology is to put efficiency and effectiveness on a pedestal, and ultimately you are a hair’s breadth away from fascism, at least as it is defined here: “The cynical action plus a taste for action makes man a fascist, or a potential fascist–unless there’s loyalty behind him” (143).

There is, however, perhaps a third option, beyond this opposition between dignified humanism on the one hand and technocratic pragmatism on the other. For the technology that does indeed pervade everything in the novel (almost always, for instance, there is a radio on somewhere in the background) has effects that are as much aesthetic as military. There are frequent comparisons with the movie industry, for instance: Madrid is described as “an enormous film studio” (36); an in Toledo “the fierce light of a film studio played on ruins like the wreckage of a temple of the East” (161); the aviator Scali is compared to “an American film comedian” (118); Hernandez’s friend Moreno’s face is described in terms of its “screen-star symmetry” (195). And at the very end of the first part of the novel, when Hernandez is facing a fascist firing squad, he thinks of it as some kind of grotesque cinematic scene: “yes, all was ready for the camera” (220).

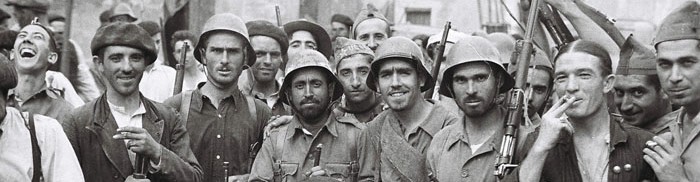

All of which suggests that the true stakes of the war (and the revolution) may not be so much moral or political as in the realm of representation. Hence, listening to “the strident triumph of fraternal unity” as a parade of troops goes by, the American journalist Slade comments that “There’s a spark of poetry [. . .] in every man, and one day he has to come out with it” (37). His friend, Lopez, replies that “we’ve here right now a mob of painters” and argues the need for a revolutionary art or “style” that’s “got to be something definite, not a vague abstraction like ‘the masses’” (38). “One day,” he continues, “that new style of ours will catch on in the whole of Spain, just as the cathedral style spread over Europe, and their painters have given Mexico a revolutionary fresco style” (40). And so perhaps this is where Malraux’s hope is invested: the Republicans may indeed lose the war, and the Revolution may indeed be doomed (may have to be doomed for it not to become itself simply the mirror image of the fascism that opposes it), but somehow an aesthetic style may survive these losses, and take hold not only in Spain but also far beyond.

See also: Days of Hope II; Spanish Civil War novels.