George Orwell’s book, Homage to Catalonia, as discussed in class, could be of many genres, specifically historical, political, and autobiographical. This memoir, is a personal account of his time during the Spanish civil war. In the beginning of the novel, Orwell describes the atmosphere and the feelings of camaraderie felt at the start of this ‘revolution’. He talks about the atmosphere in the town of Barcelona,

“Practically every building of any size had been seized by the workers and was draped with red flags or with the red and black flag of the Anarchists; every wall was scrawled with the hammer and sickle and with the initial of the revolutionary parties…Every shop and cafe had an inscription saying it had been collectivized” (3).

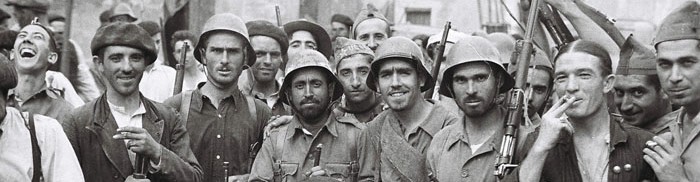

This gives the reader a sense of the feelings of how the people felt, plus the extent of control the Anarchists had over the city. The condition of the town can only be described as ‘shabby,’ ‘untidy,’ kind of sombre, which is evidently a sign of the coming war. The fact that formal speech for addressing others, was not to be used, ‘Señor’, ‘Don’, and ‘Usted,’ gives me the idea that language is also a significant part of a country and that by changing certain parts of it, is a part of the ‘revolutionary’ movement. The people have all joined the ‘workers’ side,’ which says a lot about the fear people may have of not being a part of the norm, such as the people of the bourgeoisie class. The attitudes of the people part of the revolutionary army, were obviously layed-back because of how much the Spanish people have a habit of being late. What they share in addition to that, is their goal of going against the fascists. The idea of pushing things off, delaying, being unprepared with the equipment, contributed significantly to their continuous loss. Much like in Days of Hope, feelings aren’t enough.

In Chapter V of the novel, I find it interesting how Orwell describes rats, being almost nearly as big as the size of cats, making the reference through an old army song “There are rats, rats,/ Rats as big as cats,/ In the quartermaster’s store!” (56). This makes me recall, in Orwell’s novel 1984, O’Brien, a member of the Inner party, uses psychological torture and Blackmailing through the use of rats, in-order to threaten Winston into obeying. It is clear that in both of Orwell’s works, his fear of rats is brought to light. Like most writers, what they write can reflect how they are as a person.

From Chapter VII and VIII on, there is a change in Orwells views, after experiencing the trench warfares and such, he started to become a “democratic socialist.” There seems to be a clear disappointment in his part, because once he returned to Barcelona, he felt that the revolutionary atmosphere had disappeared, perhaps due to the losses they’ve had. After all that they were fighting for, freedom and equality, the re-emergence of the class system most likely brought him down. From the start, this war, may have been a loss cause already, so why does Orwell, go back to the front to fight? Would it make much of a difference?

The political situation seemed to be unstable in Spain, perhaps one could say that thanks to this instability, Orwell and his family, were able to successfully escape prosecution. Which could be seen in Chapter XII. A question I’ve been wondering, is it possible that Orwell regretted joining the POUM? If from the start, Orwell had been on a different side to begin with, would he have been a regular journalist, or would he still eventually join the war? From the start, he was swept with the emotions of the people, that’s why he joined the revolutionary front instead of being a journalist. Given the political situation, it makes me unable to relate to his feelings because it feels like a whole other world and also since we live in a love different era, an era of peace.