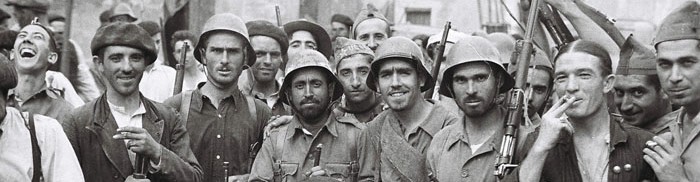

In Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls, we acquaint ourselves with the protagonist Robert Jordan, an expert dynamiter from the US who has given up his life at home to participate in the Spanish Civil War. By orders of a General Golz, he is to strategically blow up a bridge at the precise time of a Republican offensive in order to hinder the mobilization of Fascist reinforcements. In order to do this, he enlists the help of mountain guerillas of the area; he is led to guerillas’ hideout by his guide, the elderly Anselmo.

What is notable about this book specifically is its strange diction in which it goes about telling the story. Indeed it really incorporates an almost Spanish type of grammar, yet it is largely executed in English, with light Spanish punctuations here and there. The sentences are not incorrect, but they feel like direct translations of sentences first written in Spanish. This is particularly true for inter-character dialogue, but less so for the narration.

What I particularly enjoyed about this book is that it portrays very real experiences, human experiences, and with that, clear and substantial emotions. Hemingway deliberately takes the more palpable parts of the war and the human condition to his audiences, depicting the more basic, primordial side of people: hunger, lust, killing, and death. There is much that goes on behind the lines and in between battles; people get hungry, and food must be prepared (as in the first chapter). As well, Robert Jordan and Maria make love in the woods. There is constant talk of killing and death among the guerillas of the camp, and later in the book, the actual killing commences. As discussed in class, there is indeed a certain universality to this book and its characters, where such experiences could have been lived by anyone and at any time; war, killing, and love are forever.

Hemingway moves on to create more complex emotions as well, putting the reader in difficult situations just as the characters face. As an example, there is a very real uneasiness as the people of the cave plot to kill Pablo, and we later find out from Pilar that almost certainly has Pablo overheard the conversation.

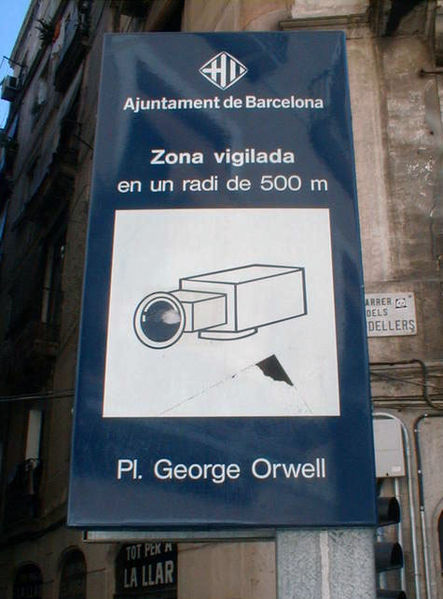

In the same vein, he neglects to substantially explain the political motivations and underpinnings of the war. Perhaps Hemingway did not want to bog down his book with overly complicated and hardly relatable struggles of ideal (and the inevitable battle of acronyms) that plagued the earlier books we have read. We learn very little about the situation in Spain of that epoch, and as a novel of historical fiction, it serves more as fiction than historical.

Nonetheless, I enjoy its simple prose and I look forward to reading the rest of this book.