Más errores de apreciación

en El Entenado de Juan José Saer

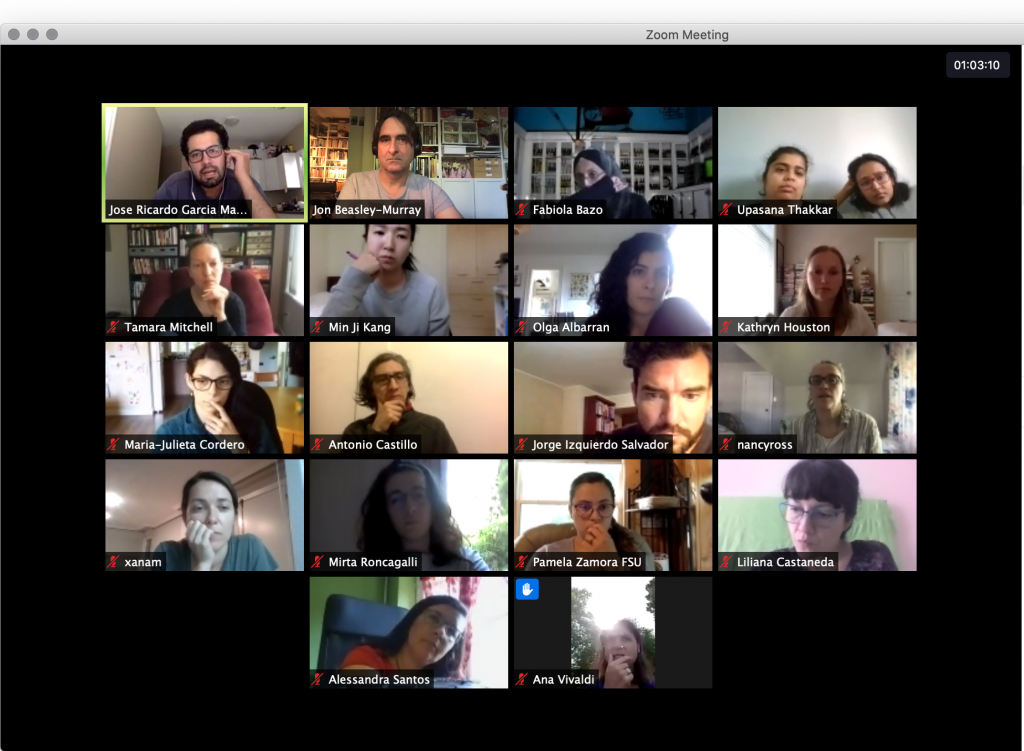

Por Jorge Izquierdo

PhD en Estudios Hispánicos de la Universidad de Columbia Británica (University of British Columbia)

Actualmente Docente y Coordinador Académico de UDLA Honors, Universidad de las Américas, Quito-Ecuador

Co-fundador de Editorial Festina Lente

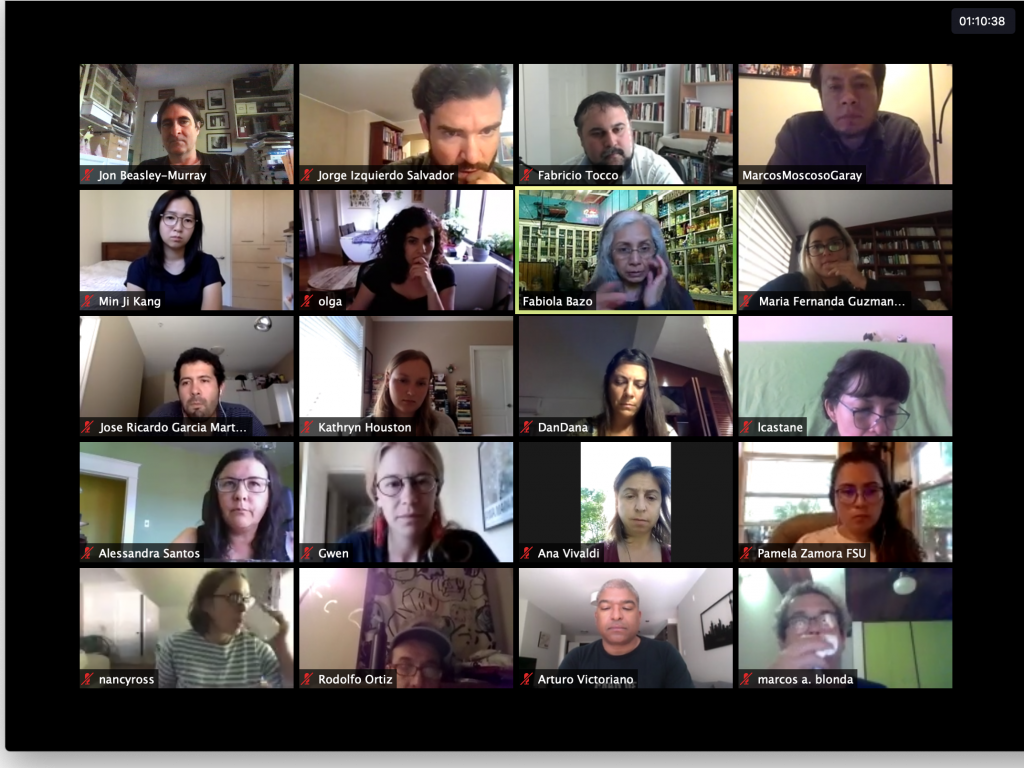

A lo largo de nuestras reuniones en el Virtual Koerner´s me he preguntado: ¿Dónde está América Latina? A pesar de que el grupo no tiene el propósito exclusivo de tratar temas de América Latina, me hago la pregunta porque con frecuencia estos temas sí aparecen y entonces, se produce en mí un cortocircuito geográfico. Estoy frente a mi pantalla en Quito, Ecuador, mientras que la mayoría de las personas con las que converso se hallan frente a sus pantallas en el Norte. No es un cortocircuito devastador, yo mismo he vivido varios años en el Norte, he aprendido allá, sé lo que está ocurriendo, pero sospecho, al recibir la corriente eléctrica, nada más.

Hace poco leímos y nos reunimos con Erin Graff Zivin de USC. La experiencia fue valiosa. Las ideas planteadas y el diálogo me parecieron ricos. Sin embargo, me llamó la atención una cierta metodología que creí notar. Quizás me equivoque al respecto, pero percibí que esa metodología consistía en apoyarse en teóricos franceses para cerrar, apenas, con la lectura detenida de un texto por un autor argentino. ¿Es esa la manera de proceder de los y las latinoamericanistas? En parte sí y no creo que haya ningún problema en ello. Argentina es parte de América Latina, después de todo, y no existe ninguna prohibición acerca de citar a teóricos franceses, casi que sucede lo contrario. Solo menciono esta nueva sospecha porque, para alguien trabajando y produciendo desde el Ecuador, resulta que algo falta o que la cosa sobrevuela por encima, distante. Asimismo, intuyo que lo que yo comparto desde aquí con ustedes, anda por debajo como un bicho rastrero.

Me cautivaron particularmente las ideas de Graff Zivin alrededor del malentendido en la literatura. Su lectura breve de El entenado (1983), la novela de Juan José Saer, me pareció profunda. Graff Zivin además registra otras lecturas académicas que se han hecho sobre la misma novela, marcando por qué la suya puede ser diferente. A partir de ese intercambio me motivé a leer El entenado. La novela está ambientada en la experiencia de la conquista del territorio Latinoamericano y en el testimonio de un europeo que vivió como cautivo por diez años en una tribu de indígenas que habitaban alrededor de lo que hoy es Santa Fe, Argentina. Luego de leerla solo me cupo preguntar por qué Graff Zivin no la exploró incluso más, leyendo más partes del texto que apoyaran su postura. Más Saer y menos Ranciere, por decirlo de alguna manera.

Me cautivaron particularmente las ideas de Graff Zivin alrededor del malentendido en la literatura. Su lectura breve de El entenado (1983), la novela de Juan José Saer, me pareció profunda. Graff Zivin además registra otras lecturas académicas que se han hecho sobre la misma novela, marcando por qué la suya puede ser diferente. A partir de ese intercambio me motivé a leer El entenado. La novela está ambientada en la experiencia de la conquista del territorio Latinoamericano y en el testimonio de un europeo que vivió como cautivo por diez años en una tribu de indígenas que habitaban alrededor de lo que hoy es Santa Fe, Argentina. Luego de leerla solo me cupo preguntar por qué Graff Zivin no la exploró incluso más, leyendo más partes del texto que apoyaran su postura. Más Saer y menos Ranciere, por decirlo de alguna manera.

El artículo “Marrano Secrets; Or Misunderstanding Literature” (2014) cierra con una lectura de una escena de la novela de Saer. Es una lectura muy sugerente porque da cuenta de una temática constante del texto, la del reconocimiento del error y la de los malentendidos. La escena sobre la que Graff Zivin se detiene, ocurre al inicio del libro cuando el capitán de la expedición de la conquista parece reconocer un “error de apreciación que había venido cometiendo, a lo largo de toda su vida, acerca de su propia condición”. Instantes después, este conquistador fallido muere en una emboscada de un grupo de indígenas nativos. Es su primer y único contacto con la tierra nueva. La escena es poderosa y el misterio alrededor del mencionado error es relevante, pero, como la propia Graff Zivin admite, esta escena es apenas un detalle en la trama que se viene. El personaje del capitán no resulta ser tan importante en el transcurso del texto, es descrito de manera lejana y tibia. Se sabe que era un cortesano al cual se le encargó la misión de ir a América, se sabe que los tripulantes de las embarcaciones que lideran lo temen y respetan. Se sabe que es pensativo, aunque nunca sabemos qué piensa, y se sabe que logra detener una posible rebelión entre los marineros con una actitud determinada pero sin pronunciar una sola palabra. Es un personaje menor en el contexto de este libro que se estructura como una larga meditación, un flujo, estilo río pues no hay pausas ni capítulos. Este formato alrededor de la abundancia me parece importante, de hecho, y convierte a la selección de cualquier episodio aislado en una limitación frente al texto de Saer. Incluso el tono del protagonista alude a lo colectivo y a la idea de anonimato. No narra desde su particularidad sino en complicidad con la comunidad a la que observa. En relación a esto es interesante el momento en que el protagonista regresa a su comunidad de blancos, luego de los diez años en cautiverio, y habla a las primeras personas que ve, sin darse cuenta, por un buen rato, que no les está hablando en castellano sino en la lengua indígena que ha aprendido.

Quizás lo mejor que se puede hacer con esta novela es leerla en este sentido: total, abarcador, fluido, intraducible, dejarse llevar, no recoger una escena puntual, ni un personaje individual, sino aspirar a recogerla toda, no un tema sino varios. Y quizás este mecanismo que acabo de esbozar dice algo acerca de la posibilidad de un pensamiento del Sur que no requiere de anclas en la teoría crítica europea o en la academia del Norte.

Pero ya que estamos en la línea de pensamiento planteada por Graff Zivin, que es muy convincente y atractiva, vale recalcar de nuevo, puedo agregar que la temática del error y del malentendido se plantean en otras partes del libro e incluso con mayor fuerza que la mostrada en “Marrano Secrets”. Voy a singularizar dos escenas adicionales, a pesar de lo que acabo de sugerir en contra de la singularización. Quizás al ampliar la serie a tres, quizás al recoger, a modo de colección, se logre algo. Quizás motive más lecturas.

Escena 2: A lo largo de la novela se comentan las prácticas de canibalismo de la tribu de indígenas. Comen carne humana una vez al año, más o menos en la misma temporada, y esta experiencia, más el consumo de alcohol que la acompaña, conlleva resultados desinhibidores, carnales y misteriosos. El protagonista quiere comprender los sentidos de este ritual y en un momento logra entablar una “conversación confidencial” con uno de los indígenas de la tribu al respecto. Este hombre le explica que para otros indios ser comidos por sus enemigos puede significar un honor y que, además, (lo dice con cierto recelo) estos otros indios hasta disfrutan del hecho de ser comidos. El protagonista agrega: “Por mucho que seguí interrogándolo, no logré que me dijera más. Creí entender que el desprecio venía de lo inexplicable de esa inclinación, y que el indio la consideraba como un gusto equívoco, perverso… comer carne humana no parecía ser tampoco una costumbre de la que se sintiesen muy orgullosos…”. En el mismo contexto, poco después se agrega que “Si, cuando empezaban a masticar, el malestar crecía en ellos, era porque esa carne debía tener, aunque no pudiesen precisarlo, un gusto a sombra exhausta y a error repetido” (énfasis mío).

Escena 3: El entenado cierra con tres recuerdos adicionales, aleatorios, sobre la vida en cautiverio. El segundo de esos recuerdos tiene que ver con un indígena moribundo, a quien el protagonista había conocido desde hacía tiempo y al que siempre había guardado en alta estima por su serenidad y amabilidad. Su muerte coincide con uno de los rituales de canibalismo y desenfreno sexual. En el recuerdo del protagonista, se lo ve al indio tirado sobre la arena de una playa, la mañana siguiente a la fiebre y el pandemonio, su cuerpo mutilado, su mirada perdida. “Su agonía” nos dice “confirmaba, inacabable, mi error” (énfasis mío). Este es un error de apreciación, al igual que el que experimenta el capitán, misteriosamente, al inicio de la novela, como mal presagio de su muerte. En este caso, sin embargo, llegamos a conocer mucho más. El protagonista retrocede en el tiempo para descifrar cómo este amigo indígena, lúcido en principio, se había transformado en un ser errático, ambicioso, malgenio y fatal, lo describe paso a paso en el día y la noche previa a su muerte. La lección que saca de todo esto es que una vida se mide completa, no de manera parcial; es decir, puedes ser paciente y amable todos los días de tu existencia menos uno. También concluye que la muerte es individual, el recuerdo de una vida no vale mucho, sugiere, quizás, frente a la experiencia abierta y tenaz de la muchedumbre: “Del hombre magullado, que ya apenas si respiraba, aprendí, también, aquella mañana, que, de la negrura que nos rodea, la virtud no salva”.

Dejo estas ideas en un intento por ampliar el intercambio que sostuvimos con Erin Graff Zivin, que me pareció enriquecedor y productivo. Asimismo, he aprovechado la ocasión para entablar ciertas discrepancias que siento en un nivel sensible, no racional (y desde el Ecuador) con los estudios latinoamericanos.

Thanks to everyone who took part in this week’s discussion. It was great to have more new people joining us, this week from California and the mines of New Mexico.

Thanks to everyone who took part in this week’s discussion. It was great to have more new people joining us, this week from California and the mines of New Mexico.

First, I must apologize for how late this post is. I was out of town last week, and more distracted than I anticipated. (Yes, within British Columbia we can travel! Even if we can never again leave this beautiful province…)

First, I must apologize for how late this post is. I was out of town last week, and more distracted than I anticipated. (Yes, within British Columbia we can travel! Even if we can never again leave this beautiful province…) We now move on to a new cycle of sessions, which will culminate in a visit from Argentine political theorist Diego Sztulwark on July 29. This series is organized by Ana Vivaldi, who has invited Sztulwark and suggested the preparatory readings.

We now move on to a new cycle of sessions, which will culminate in a visit from Argentine political theorist Diego Sztulwark on July 29. This series is organized by Ana Vivaldi, who has invited Sztulwark and suggested the preparatory readings. On July 1, we are very pleased to welcome

On July 1, we are very pleased to welcome

In her chapter, “Patriarchy: From the Margins to the Center” (from La guerra contra las mujeres [2017]), Rita Segato goes further. We are all trained to be psychopaths now, she tells us, as part of a “pedagogy of cruelty” that is the “nursery for psychopathic personalities that are valorized by the spirit of the age and functional for this apocalyptic phase of capitalism” (102). Segato presents a brief reading of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange to make her point, though what she sees as “most extraordinary” about the film is that the shock with which it was received when it came out (in 1971) now seems to have almost totally dissipated. What was once taken as itself an almost psychopathic assault on the viewer’s senses is now just another movie; this shift in our sensibility is “a clear indication [. . .] of the naturalization of the psychopathic personality and of violence” (102). The narcissistic “ultra-violence” of the gang of dandies that the film portrays is now fully incorporated within the social order that it once seemed to threaten.

In her chapter, “Patriarchy: From the Margins to the Center” (from La guerra contra las mujeres [2017]), Rita Segato goes further. We are all trained to be psychopaths now, she tells us, as part of a “pedagogy of cruelty” that is the “nursery for psychopathic personalities that are valorized by the spirit of the age and functional for this apocalyptic phase of capitalism” (102). Segato presents a brief reading of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange to make her point, though what she sees as “most extraordinary” about the film is that the shock with which it was received when it came out (in 1971) now seems to have almost totally dissipated. What was once taken as itself an almost psychopathic assault on the viewer’s senses is now just another movie; this shift in our sensibility is “a clear indication [. . .] of the naturalization of the psychopathic personality and of violence” (102). The narcissistic “ultra-violence” of the gang of dandies that the film portrays is now fully incorporated within the social order that it once seemed to threaten. We are delighted to start today with a discussion with

We are delighted to start today with a discussion with

Me cautivaron particularmente las ideas de Graff Zivin alrededor del malentendido en la literatura. Su lectura breve de El entenado (1983), la novela de Juan José Saer, me pareció profunda. Graff Zivin además registra otras lecturas académicas que se han hecho sobre la misma novela, marcando por qué la suya puede ser diferente. A partir de ese intercambio me motivé a leer El entenado. La novela está ambientada en la experiencia de la conquista del territorio Latinoamericano y en el testimonio de un europeo que vivió como cautivo por diez años en una tribu de indígenas que habitaban alrededor de lo que hoy es Santa Fe, Argentina. Luego de leerla solo me cupo preguntar por qué Graff Zivin no la exploró incluso más, leyendo más partes del texto que apoyaran su postura. Más Saer y menos Ranciere, por decirlo de alguna manera.

Me cautivaron particularmente las ideas de Graff Zivin alrededor del malentendido en la literatura. Su lectura breve de El entenado (1983), la novela de Juan José Saer, me pareció profunda. Graff Zivin además registra otras lecturas académicas que se han hecho sobre la misma novela, marcando por qué la suya puede ser diferente. A partir de ese intercambio me motivé a leer El entenado. La novela está ambientada en la experiencia de la conquista del territorio Latinoamericano y en el testimonio de un europeo que vivió como cautivo por diez años en una tribu de indígenas que habitaban alrededor de lo que hoy es Santa Fe, Argentina. Luego de leerla solo me cupo preguntar por qué Graff Zivin no la exploró incluso más, leyendo más partes del texto que apoyaran su postura. Más Saer y menos Ranciere, por decirlo de alguna manera. We will be reading and discussing

We will be reading and discussing

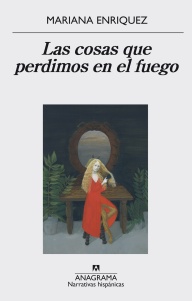

Femininity is all too often defined by the image (and so by the male gaze). Women are reduced to appearance, and judged in terms of the extent to which they measure up to some mythical ideal. Mariana Enríquez’s short story, “Las cosas que perdimos en el fuego” (“Things We Lost in the Fire”), presents a surreal and disturbing counter-mythology that explores what happens when that image is subject to attack, not least by women themselves.

Femininity is all too often defined by the image (and so by the male gaze). Women are reduced to appearance, and judged in terms of the extent to which they measure up to some mythical ideal. Mariana Enríquez’s short story, “Las cosas que perdimos en el fuego” (“Things We Lost in the Fire”), presents a surreal and disturbing counter-mythology that explores what happens when that image is subject to attack, not least by women themselves.