Listen to Class Struggle, Ira Basen’s documentary of the plight of part-time faculty in Canadian universities.

Ira Basen, CBC, September 7, 2014– Kimberley Ellis Hale has been an instructor at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ont., for 16 years. This summer, while teaching an introductory course in sociology, she presented her students with a role-playing game to help them understand how precarious economic security is for millions of Canadian workers.

In her scenario, students were told they had lost their jobs, their marriage had broken up, and they needed to find someplace to live. And they had to figure out a way to live on just $1,000 a month.

What those students didn’t know was the life they were being asked to imagine was not very different than the life of their instructor.

According to figures provided by the Laurier Faculty Association, 52 per cent of Laurier students were taught by CAS in 2012, up from 38 per cent in 2008. (Brian St-Denis (CBC News))

Hale is 51 years old, and a single mother with two kids. She is what her university calls a CAS (contract academic staff). Other schools use titles such as sessional lecturers and adjunct faculty.

That means that despite her 16 years of service, she has no job security. She still needs to apply to teach her courses every semester. She gets none of the perks that a full time professor gets; generous benefits and pension, sabbaticals, money for travel and research, and job security in the form of tenure that most workers can only dream about.

And then there’s the money.

A full course load for professors teaching at most Canadian universities is four courses a year. Depending on the faculty, their salary will range between $80,000 and $150,000 a year. A contract faculty person teaching those same four courses will earn about $28,000.

Full time faculty are also required to research, publish, and serve on committees, but many contract staff do that as well in the hope of one day moving up the academic ladder. The difference is they have to do it on their own time and on their own dime.

Precariat

The reality of Kimberley’s life would be hard for most students to grasp.

‘I never imagined myself in this position, where every four months I worry about how I’m going to put food on the table.’– Kimberley Ellis Hale, instructor

For them, a professor is a professor. How could someone with graduate degrees who teaches at a prestigious university belong to what sociologists now call the “precariat, ” a social class whose working lives lack predictability or financial security?

It’s a question that Kimberley often asks herself.

“I never imagined myself in this position,” she says in an interview at her home later that day, “where every four months I worry about how I’m going to put food on the table. So what I did with them this morning is try to get them to think, ‘Well what if you were in this position?’”

Contract faculty

In Canada today, it’s estimated that more than half of all undergraduates are taught by contract faculty.

Not all of those people live on the margins. In specialized fields like law, business and journalism, people are hired for the special expertise they bring to the field. They have other sources of income. And retired professors on a pension sometimes welcome the opportunity to teach a course or two.

But there are many thousands of people trying to cobble together a full-time salary with part-time work.

They often teach the large introductory courses that tenured faculty like to avoid. They put in 60- to 70-hour weeks grading hundreds of essays and exams, for wages that sometimes barely break the poverty line.

It’s what Kimberley Ellis Hale calls the university’s “dirty little secret.”

Our universities are rightly celebrated for their great achievements in research. That’s what attracts the money, the prestige and the distinguished scholars. But the core of the teaching is being done by the most precarious of academic labourers.

And without them, the business model of the university would collapse.

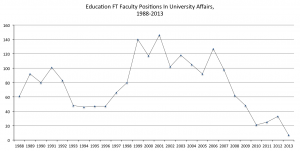

Enrollment at Canadian universities is soaring (up 23 per cent at Laurierover the past decade, for example). And while most universities are still hiring tenure-track faculty, they aren’t hiring enough to match the growing student population. So classes are getting bigger, and more “sessional” instructors are being hired.

“It helps financially,” concedes Pat Rogers, Laurier’s vice-president of teaching. “If you can’t afford to hire a faculty member who will only teach four courses, you can hire many more sessional faculty for that money.

“Universities are really strapped now. I think it’s regrettable, and I think there are legitimate concerns about having such a large part-time workforce, but it’s an unfortunate consequence of underfunding of the university.”

Read More: CBC, “Most University undergrads now taught by poorly paid part-timers”

Follow

Follow THE CASE OF THE MISSING SCULPTURE

THE CASE OF THE MISSING SCULPTURE

Dark Days for Our Universities

[Recent events at Capilano University and University of Saskatchewan have raised serious concerns about the health of the academic culture of post-secondary institutions in Canada. Crawford Kilian, who taught at Capilano College from its founding in 1968 until it became a university in 2008, wrote the following analysis of Canadian academic culture for The Tyee, where he is a contributing editor. The Institute for Critical Education Studies at UBC is pleased to reprint the article here, with the author’s permission.]

Dark Days for Our Universities

Dr. Buckingham’s censure only confirms the long, tragic decline of Canadian academic culture

Crawford Kilian

(Originally published in TheTyee.ca, May 19, 2014)

On May 13 I attended a meeting of the Board of Governors of Capilano University, which has had a very bad year.

Last spring the board agreed to cut several programs altogether. This caused considerable anger and bitterness, especially since the recommendations for the cuts had been made by a handful of administrators without consulting the university senate.

Recently, the B.C. Supreme Court ruled that the board’s failure to consult with the senate was a breach of the University Act. This upset the board members, who may yet appeal the decision.

Adding to the angst was the disappearance of a satirical sculpture of Cap’s president, Kris Bulcroft, which had been created and displayed on campus by George Rammell, an instructor in the now-dead studio arts program. Thanks to media coverage, the sculpture has now been seen across the country, and by far more people.

Board Chair Jane Shackell (who was my student back in 1979) stated at the meeting that she had personally ordered the removal of the sculpture because it was a form of harassment of a university employee, the president. Rather than follow the university’s policy on harassment complaints (and Bulcroft had apparently not complained), Shackell seemed to see herself as a one-person HR committee concerned with the president alone.

At the end of the meeting another retired instructor made an angry protest about the board’s actions. Like the judge in a Hollywood court drama, my former student tried to gavel him down.

I didn’t feel angry at her; I felt pity. It was painfully clear that she and her board and administration are running on fumes.

The mounting crisis

I look at this incident not as a unique outrage, but as just another example of the intellectual and moral crisis gripping Canadian post-secondary education. The old scientific principle of mediocrity applies here: very few things are unique. If it’s happening in North Vancouver, it’s probably happening everywhere.

And it certainly seems to be. On the strength of one short video clip, Tom Flanagan last year became an unperson to the University of Calgary, where he’d taught honourably for decades. He was already scheduled to retire, but the president issued a news release that made it look as if he was getting the bum’s rush.

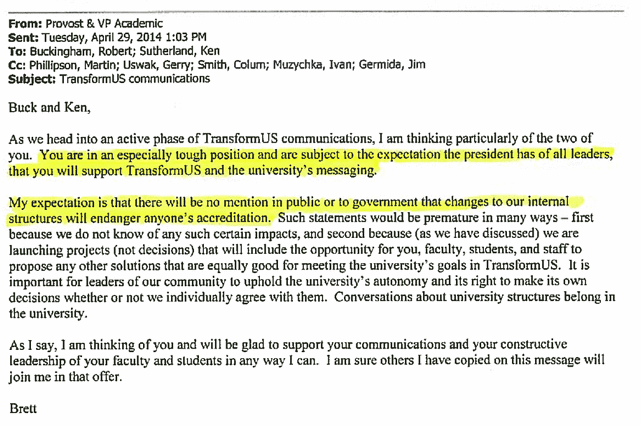

More recently, Dr. Robert Buckingham publicly criticized a restructuring plan at the University of Saskatchewan, where he was dean of the School of Public Health.

In a 30-second interview with the university provost, he was fired and escorted off campus.

A day later the university president admitted firing him had been a “blunder” and offered to reinstate him as a tenured professor, but not as a dean. It remains to be seen whether he’ll accept.

The problem runs deeper than the occasional noisy prof or thin-skinned administrator. It’s systemic, developed over decades. As the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives noted last November, the University of Manitoba faculty very nearly went on strike until the president’s office agreed to a collective agreement ensuring professors’ right to speak freely, even if it meant criticizing the university.

Universities ‘open for business’

At about the same time, the Canadian Association of University Teachers published a report, Open for Business. CAUT warned about corporate and government deals with universities that would ditch basic research for more immediately convenient purposes.

“Unfortunately,” the report said, “attempts by industry and government to direct scholarly inquiry and teaching have multiplied in the past two decades…. For industry, there is a diminished willingness to undertake fundamental research at its own expense and in its own labs — preferring to tap the talent within the university at a fraction of the cost.

“For politicians, there is a desire to please industry, an often inadequate understanding of how knowledge is advanced, and a short time horizon (the next election). The result is a propensity to direct universities ‘to get on with’ producing the knowledge that benefits industry and therefore, ostensibly, the economy.”

This is not a sudden development. The expansion of North America’s post-secondary system began soon after the Second World War and really got going after Sputnik, when the Soviets seemed to be producing more and better graduates than the West was. That expansion helped to fuel decades of economic growth (and helped put the Soviets in history’s ashcan).

Throughout that period, academic freedom was in constant peril. In the Cold War, U. S. professors were expected to sign loyalty oaths. In 1969-70 Simon Fraser University went through a political upheaval in which eight faculty members were dismissed and SFU’s first president resigned.

A Faustian bargain

What is different now is that Canadian post-secondary must depend more and more on less and less government support. Postwar expansion has become a Faustian bargain for administrators: to create and maintain their bureaucracies and programs, post-secondary schools must do as they’re paid to do. If public money dwindles, it must be found in higher student fees, in corporate funding, in recruiting foreign kids desperate for a Canadian degree.

So it’s no surprise that Dr. Buckingham was sacked for criticizing a budget-cutting plan to rescue an ailing School of Medicine by putting it into Buckingham’s thriving School of Public Health.

And it’s no surprise that Capilano University had shortfalls right from its announcement in 2008. It had to become a university to attract more foreign students than it could as a mere college, but at the last minute the Gordon Campbell Liberals reneged on their promise to give it university-level funding.

For six years, then, Cap’s board and administration have known they were running on fumes. They are in the same predicament as B.C. school boards, who must do the government’s dirty work and take the blame for program and teacher cuts.

In 40 years of teaching at Cap, I rarely attended board meetings, and never did a board member visit my classes. I don’t know the members of this current board, apart from a couple of faculty representatives, but I’ve served as a North Vancouver school trustee. As an education journalist I’ve talked to a lot of university and college administrators, not to mention school trustees. I know how they think.

Managing the decline

For any school or university board, underfunding creates a terrible predicament: protest too loudly and you’ll be replaced by a provincial hireling who’ll cut without regard for the school’s long-term survival. If you have any love for the institution, you can only try to do damage control. But when your teachers or professors protest, as they have every right to, that annoys and embarrasses the government. It will punish you for not imposing the “silence of the deans” on them.

University presidents and senior administrators make six-figure salaries and enjoy high prestige. They are supposed to be both scholars and managers. Their boards are supposed to be notable achievers as well, though their achievements have often been in the service of the governing party. Their education has served them well, and now they can serve education.

But a Darwinian selection process has made them servants of politics instead, detached from the true principles of education. When they realize that their job is not to serve education but to make the government look good, they panic. Everything they learned in school about critical thinking and reasoned argument vanishes.

In reward for previous achievements and political support, the B.C. government appointed Cap’s board members to run the school without giving them the money to run it well, or even adequately. And whatever their previous achievements, they have lacked the imagination and creativity — the education — to do anything but make matters worse. Faced with an angry faculty and a humiliating court judgment, they have drawn ridicule upon themselves and the university.

They can’t extricate themselves and they have no arguments left to offer — only the frantic banging of a gavel that can’t drown out the voice of an angry retired prof exercising his right to speak freely. [Tyee]

Comments Off on Dark Days for Our Universities

Posted in Academic freedom, Academics, BC Education, Commentary, Corporate University, Working conditions

Tagged academic culture, Administration, British Columbia, Capilano University, Corporate University, Crawford Kilian, Robert Buckingham, tenure, The Tyee, University of Saskatchewan