I have submitted a proposal to two different conferences, for a session in which we would discuss the possibility and methods of researching the effectiveness of cMOOCs. One of those conferences is still considering the proposal, but as soon as decisions are made there I’ll post the proposal itself here on my blog. The proposal was accepted for a poster presentation at one conference, but I’m still waiting to hear from the other.

If the session gets accepted, I’ll need to give some background to cMOOCs in the way of talking about connectivism. And I want to dig my way through connectivist ideas anyway, so I’m going to do so here on the blog. That’s the way I think through things best–writing about them (or teaching, but I’m on sabbatical at the moment and not teaching).

I have read a number of articles and blog posts by George Siemens on connectivism, and have bookmarked quite a few others by Stephen Downes. Here I’ll discuss Siemens’ arguments, at least those I’ve found so far. I will not address the question of whether this is really a “new” learning theory, or whether it’s a learning theory at all, which are some issues that have been discussed in the research literature. I’m also not going to comment on the relationships between connectivism and constructivism, behaviourism, and cognitivism, as I have a woeful lack of knowledge of such theories. I’m just going to try to figure out some of (not all of) the basic ideas/arguments in what Siemens has written, and give my comments.

Context for the view

Siemens argues that connectivism makes sense for a context in which people have relatively access to a very large amount of information (through, e.g., the world wide web–not saying that everyone does have such access, but for those who do, Siemens is claiming, connectivism makes sense), can use technology to store that information rather than needing to have it in their own heads, and in which what counts as “knowledge” changes rapidly such that it becomes obsolete relatively quickly compared to past centuries and even decades (Siemens, 2005a). He claims we need a new learning theory, a new way of understanding how learning and knowledge work, within this sort of context.

Learning as a process of forming connections

To me, this is one of the fundamental ideas in connectivism, and the one I’m most interested in. I want to pick apart some of what Siemens says about it, in order to understand it better.

Learning is a process of connecting specialized nodes or information sources. (Siemens, 2005a)

I perceive learning as a network formation process. (Siemens, 2006b)

To really get at what is going on here, one would probably need to know more about learning theory than I do (as in, something about it, which I don’t). But the general idea is that when one learns something, what happens is that one makes connections between…what? Nodes. What counts as a “node”?

Siemens explains that networks have both nodes and connections, and “a node is any element that can be connected to any other element. A connection is any type of link between nodes” (Siemens, 2005b). He notes in (Siemens 2005a) that nodes can be, e.g., “fields, ideas, communities,” among other things. He also speaks of people as nodes. In this presentation posted by the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (starting at around 7 minutes), Siemens describes teaching a course as a process of directing the formations of connections for students–when we given them particular course content, particular texts, particular theories to study and discuss, we are guiding how they form connections. The scope of “nodes” is very wide:

Virtually any element that we can scrutinize or experience can become node. Thoughts, feelings, interactions with others, and new data and information can be seen as nodes. (Siemens, 2005b)

Thus, connections can be made between nodes as persons, as ideas, as sets of data, as texts (or other media, such as videos), as groups, and more. So if I learn something, I make a connection (in my mind?) between myself and, say, a text, and between ideas I already have and those I’m getting from the text. I think that’s right, but I’m not absolutely certain, especially about the location of the connections–can some connections be located in thoughts, others outside? Siemens is clear that “[l]earning may reside in non-human appliances” (Siemens, 2005a), so clearly he thinks the connections don’t have to be only internal. But can they be internal at all? I’ll return to this question below.

First, briefly: How can learning reside in non-human appliances? If learning is a process of making connections, then appliances such as computers, and the software that runs on them, as well as the whatever that nebulous thing is that is sometimes called the “web,” could be considered as facilitating the making of connections. I make connections between myself and other persons, between my ideas and theirs, between my ideas and new information, quite often these days through the medium of these non-human entities. I suppose it is in that sense that learning, as a process of connection formation, can “reside” in non-human appliances. In a blog post entitled “What is the Unique Idea in Connectivism?”, Siemens explains the role of technology a bit further:

… technology plays a key role of 1) cognitive grunt work in creating and displaying patterns, 2) extending and enhancing our cognitive ability, 3) holding information in ready access form (for example, search engines, semantic structures, etc). (Siemens, 2006d)

Under (1), technological appliances like computers and software can create links and patterns, but also (2) extend our cognitive ability, which to me means that we can think through and understand many things more quickly and easily when we can quickly see and read and watch a number of resources about them. (3) is related to this too–the information is stored and readily accessible (well, sometimes readily…sometimes it’s quite hard to find) so that we don’t have to store it in our own, individual minds. The latter is true of textual technology like books, too. So if learning is a process of forming connections, then non-human entities can be and often are an important part of that process.

One might want to object that the appliances merely make possible these connections, that the connections themselves occur, somehow, mostly internally to individuals. One might think of the connection between some ideas I have already and some new ones I am introduced to in this way–the connection between these, however that might be characterized (and that’s a big question), seems to be localized in my own mind.

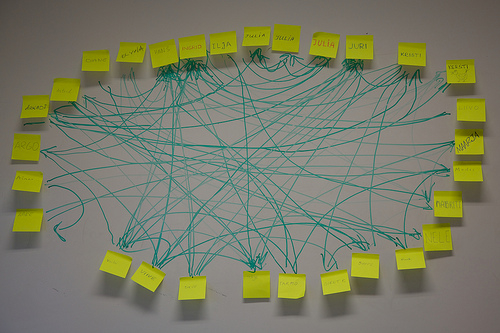

But what about the “connection” between myself and someone I communicate with entirely through the internet and the applications that allow me to do so? In what does it consist? Is it an abstraction in my mind? A feeling I have that I am linked to someone? Perhaps it makes more sense to think of this connection in terms of thoughts, feelings, plus tangible evidence of the connections in the form of emails, posts to social networks like Twitter, Google+, Facebook, video chats on Google Hangout or Skype, work that is collaboratively produced, and more. Some of these connections can be traced and visualized, such as connections on twitter being tracked and visualized through Martin Hawksey’s Twitter Archiving Google Spreadsheet (TAGS). Here’s a spreadsheet I made through TAGS for the #ds106zone Twitter hashtag, for May 23-31, 2013. And here’s the visualization of the connections on that hashtag for those seven days.

Thus, connections could, I think, be both in an individual’s mind in some way (however one might understand connections between ideas), and also located outside an individual as well.

Learning and knowledge

In reading some of Siemens’ articles and blog posts, I found myself getting confused as to the exact meanings of these tw0 terms, so I want to explore them further here. Learning is discussed briefly above as the process of making connections between nodes. What about knowledge?

Knowledge is defined as a particular pattern of relationships and learning is defined as the creation of new connections and patterns as well as the ability to maneuver around existing networks/patterns.

Our knowledge resides in the connections we form – where to other people or to information sources such as databases. (Siemens, 2006d; emphasis mine)

Siemens here suggests that while learning is a process of creating connections and patterns (as well as the ability to move around existing ones…though frankly I’m not quite sure what that means), knowledge is a particular pattern itself. In “Connectivism: Learning theory or pastime of the self-amused?” he states that knowledge “resides in a distributed manner across a network,” rather than being only in the mind of an individual (Siemens, 2006a, p. 10).

This “externalization of our knowledge,” he states in the same article, “is increasingly utilized as a means of coping with information overload” (p. 11):

Most learning needs today are becoming too complex to be addressed in “our heads”. We need to rely on a network of people (and increasingly, technology) to store, access, and retrieve knowledge and motivate its use. (Siemens, 2006c)

We have access to and can use so much information that we must externalize it through various means, such as storing it in handwritten notes, printed papers, or digital works such as texts, images, videos.

But what does it mean, exactly, to say that knowledge is a certain “pattern” of connections? The best way I can make sense of this for myself is with an example. Let’s say I know how to make an animated gif. We’ll ignore for the moment how it is I know that I know this, if I’m just trying to figure out the theory that would explain knowledge in the first place. How did I learn how to do this? I connected to a course called “ds106” (Digital Storytelling 106), which connected me to the instructor (Jim Groom), who connected me (through Twitter) to two tutorials on how to do it–a wiki page and a video. What/where is my “knowledge” of how to do this? Partly in my head, but partly not because I can’t (yet) remember each step. So partly it’s in the tutorials and the links I have to those on my computer, and partly in my link to the instructor whom I could ask questions of, and partly in my links to the other participants in the course who could help me as well. I can see, then, why one might say that the “knowledge” is not just what’s in my head, but also in some way “in” these connections. Of course, I could get to the point where I remember how to make an animated gif and so don’t need to access those connections for the basic procedure, but I would need to access the people and/or a web search if I wanted to do anything more advanced with gifs (which I did with the one linked above).

But what I’d like to see is some clearer and more detailed arguments on what counts as “knowledge” to justify why I should think of these connections I have to information on the web and to other people as part of my knowledge set. I am not an epistemologist, and haven’t studied epistemology since grad school, so I can’t go very far in criticizing this view from a philosophical perspective. I would, nevertheless, like to see a more fully worked-out argument for this view of knowledge.

In the connectivist view according to Siemens, then, it seems that learning is the process of creating patterns through developing connections, and knowledge is a resulting pattern within a network. Both, I think, can have both internal and external elements (knowledge can be a pattern of connections as abstract ideas and their logical links, e.g., as well as a connection stored in a computer text or video file).

But I get confused reading some of Siemens’ texts, because at times these words are defined slightly differently. For example, in Siemens (2006a), learning is stated to be the network itself: “The learning is the network” (p. 16), whereas I was thinking of learning as the process of making connections and then knowledge residing in the network thus created. He says the same thing in a blog post: “The network itself becomes the learning” (Siemens, 2006c). Perhaps this ambiguity is just the result of working this view out over a series of writings, which would be completely understandable. Blog posts, after all, may be treated by their authors as drafts of ideas, working through one’s views over time (I certainly view mine that way).

“The pipe is more important than the content within the pipe” (Siemens, 2005a)

This claim reflects the idea that since what counts as our “knowledge” is not only in our own heads but also outside of us, in a pattern of connections that is located partly in our own minds (and neurons!), partly in connections stored on computers, on paper, or technology (as discussed above), and partly in the links we have to other people, then what is most important is not what we have in our minds at any given moment, but the nature of these connections. When we have a problem we need to solve, for example, we don’t have to turn to the knowledge stored in our brains, but can turn to a web search, to people we’re connected with, to a course, or other sources to get the information/skills we need. “As knowledge continues to grow and evolve, access to what is needed is more important than what the learner currently possesses,” so “[n]urturing and maintaining connections is needed to facilitate continual learning” (Siemens, 2005a).

This, of course, has implications for teaching and learning: if we were to follow the connectivist view as teachers, we would not emphasize providing content to students. As many of us have already realized, at least some of the content we could provide is readily available to students on the web (This depends on the course, of course; I would say that my own interpretations of philosophical texts are not readily available, even though students could find others’ interpretations on the web pretty easily. But then again, if I post my interpretations as lecture notes on the web, then it would be available to them already.) Instead, the instructor could spend time with the class discussing, criticizing, asking and answering questions, etc.

And we could also help them with their “connectivist” skills–for lack of a better term (my term). We could help them with finding and evaluating information and information sources, for example, and with forming a network of people that can help them (and that they can help) in regards to a particular topic/field. Siemens (2008) provides a summary of various activities and roles for “connectivist” educators.

My current thoughts

Besides some slipperiness in terminology, the basic idea here makes sense. We could think of learning as a process of making connections, and knowledge as the patterns of connections thus made (if, that is, I’ve got the view right, which I might not of course). And in a context in which the internet makes information fairly easy to access (recognizing the problems with search engines filtering results in various ways) and connections to other people fairly easy to make (recognizing that people are most likely going to connect to others who are connected to who they already know, and those they tend to agree with most), I can see that the ability to make and access connections would be more important than what one “knows” in the sense of having information stored in one’s brain. One could also think of all learning as a matter of connecting things, whether it be making a connection to a book, a web page, a person, a video, etc., one might say that I am learning through making connections. I am also learning through adding the new information and skills I get thereby to my existing set, and making connections in that way as well.

I’m not convinced that this is the best way to think of learning and knowledge, at least not yet. The main problem is that I know nothing of learning theory, so I don’t know the other options. Another problem is, as noted above, I don’t think Siemens has a clearly worked-out, detailed epistemological view in the articles and blog posts I’ve read (as a philosopher I want many more specific and clear arguments supporting this view of knowledge). So while I think it makes some sense, I’m not convinced at the moment that I should accept Siemens’ view of connectivist understandings of learning and knowledge.

I think, however, that Stephen Downes has more arguments about connectivist epistemology in his writings, so that is who I’ll turn to next, in an upcoming post.

Your thoughts

Have I done justice to Siemen’s arguments about connectivism? What do you think of them? Please let us know in the comments!

Works cited

Siemens, G. (2005a). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 1(2). Retrieved from http://itdl.org/journal/jan_05/article01.htm

Siemens, G. (2005b). Connectivism: Learning as network-creation. Retrieved from http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/networks.htm

Siemens, G. (2006a). Connectivism: Learning theory or pastime for the self-amused? Retrieved from http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/connectivism_self-amused.htm

Siemens, G. (2006b, April 6). Learning, assessment, outcomes, ecologies. [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.connectivism.ca/?p=57

Siemens, G. (2006c, June 21). Constructivism vs. connectivism [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.connectivism.ca/?p=65

Siemens, G. (2006d, Aug. 6). What is the unique idea in connectivism? [Web log post] Retrieved from http://www.connectivism.ca/?p=116

Siemens, G. (2008). Learning and knowing in networks: Changing roles for educators and designers. IT Forum. Retrieved from http://itforum.coe.uga.edu/Paper105/Siemens.pdf