敬請參會

An Invitation to Participate

When the Himalaya Meets with Alps:

當喜馬拉雅山與阿爾卑斯山相遇:

International Forum on Buddhist Art & Buddhism’s Transmission to Europe 佛教藝術暨佛教在歐洲的傳播國際高峰論壇

作為世界三大宗教,佛教在其漫長的傳播過程中,一方面不斷地將其固有的印度藝術傳播至南亞之外的廣闊區域,同時也在當地與本土的文化與藝術傳統相結合,不斷地推陳出新,創造了眾多的令人炫目的藝術傳統。佛教深廣的傳播歷史也是人類藝術發展進程中不可分割的極為重要的一部分。As one of the world’s three major religions, during the long process of its transmission, Buddhism continuously disseminated Indian art across vast regions outside of South Asia. At the same time, Buddhism fused with local native cultural and artistic traditions, unceasingly creating new from the old and bringing about the development of numerous new dazzling artistic traditions. The history of the far-reaching transmission of Buddhism is an extremely important, inseparable part of the overall process of development of the arts of mankind.

在工業化文明之前,佛教的傳播侷限於亞洲;伴隨工業化而來的殖民主義狂流意外地在歐洲催生了研究印度與佛教的熱潮。隨著佛學的勃興,各種佛教傳統也陸續傳入歐洲。在過去的二、三百年內,佛教文明與歐洲文明已經在不同層面──宗教、哲學、語言、文學等──發生了碰撞,迸發出了光彩奪目的學術與文化的金石火花。然而,在其最為璀璨的核心──藝術──之上,佛教文明與歐洲文明卻尚未產生本當同等精彩與富有張力的對話與交流。During the pre-industrial age, the transmission of Buddhism was confined to Asia. Following industrialization, the rapid spread of colonialism across the world stimulated an upsurge of academic interest in India and Indian Buddhism. Along with the vigorous development of Buddhist Studies, all traditions of Buddhism one after another reached Europe. In the past two to three hundred years, Buddhist and European civilizations have clashed at different points of contact, such as religion, philosophy, language, literature, etc., producing a surge of outstanding academic and cultural output. However, Buddhist and European civilizations have not yet fostered equally lively and rich dialogue and exchange pertaining to the sphere of art.

為了彌補這一缺憾,廣東天柱慈善基金會與歐盟歐中友好協會, 聯袂美、亞數所大學與研究機構(包括中國大陸的中山大學哲學系、武漢大學健康禪研究中心、香港中文大學禪與人類文明研究中心、 與加拿大英屬哥倫比亞大學佛學論壇 )共同發起 本次國際高峰論壇,聚焦兩大主題:佛教在歐洲的傳播與研究,以及佛教藝術。兩大主題各自獨立,又可產生某種交叉與融合。佛教藝術雖然以印度的固有文明為主體,但它很早就已經同與歐洲同根同源的亞利安文明相結合;在其傳播至中亞之後而興起的犍陀羅佛教藝術,其中更深刻地滲透進了古希臘藝術的基因。歐洲學者最早醉心於佛學,佛教藝術所散發出的那種與歐洲藝術傳統若即若離、似非反是的況味應有著千絲萬縷的關聯 。因此,將佛教在歐洲的傳播與佛教的藝術傳統結合起來進行研究,可期相得益彰之效。本論壇歡迎對兩大主題各子題的研究,諸如:To remedy this situation, the Tianzhu Association of Philanthropy and the Association Amitié Euro-Chinoise (AAEC), in collaboration with several universities in Asia and North America, including the Department of Philosophy at Sun Yat-sen University in mainland China, Research Institute for Health Chan at University of Wuhan, Research Center for Chan Buddhism and the Human Civilization at Chinese University of Hong Kong, and the UBC Buddhist Studies Forum in Canada, have convened this summit forum of Buddhist Studies, by focusing on the following two primary subjects: Buddhism’s transmission and study in Europe, and Buddhist art. These two subjects are independent from each another, but at the same time are able to facilitate a certain level of overlapping and integration. Although Buddhist art is primarily centered around the native civilization of India, early on it had already become integrated with Aryan civilization which shares a common origin with the European civilization. The spread of Buddhism to Central Asia was followed by the rise of Gāndhāran Buddhist art, which was also significantly influenced by ancient Greek art. European scholars were the first to have become deeply engrossed in Buddhist studies, which in certain ways might have been closely linked to the peculiar characteristics of the Buddhist artistic tradition and its complex relations with its European counterpart. Therefore, it can be expected that the study of Buddhism’s transmission to Europe and the study of Buddhist art may be conducted jointly, complementing each other. The present Forum welcomes research presentations related to the two primary subjects and their sub-topics, such as:

- 佛教在歐洲的傳播與研究Buddhism’s transmission to and study in Europe:

1.1.佛教在歐洲傳播的歷史The history of Buddhism’s transmission to Europe;

1.2. 佛教與歐洲哲學家Buddhism and European philosophers;

1.3. 佛教與東方主義的興起Buddhism and the rise of orientalism;

1.4. 歐洲人對印度與佛教的想像與誤解European notions and misconceptions regarding India and Buddhism;

1.5. 歐洲學術傳統與印度學-佛教學的興起與演變European academic tradition and Indology: the rise and evolution of Buddhist Studies;

1.6. 佛教與歐洲心理學Buddhism and European psychology;

1.7. 佛教與歐洲新銳文學與藝術流派的興起與發展Buddhism and new European schools of literature and art;

1.8. 佛教與歐洲理性主義Buddhism and European rationalism;

1.9. 佛教與歐洲固有宗教(天主教、基督教等)的交流與衝突Buddhism and European religions (such as Catholicism and Christianity): interactions and contradictions;

1.10. 佛教與歐洲教育Buddhism and European education;

1.11. 十七世紀以來歐洲傳教士對漢傳佛教的傳譯European missionaries’ translations of Chinese Buddhist literature from the 17th century on.

- 佛教藝術Buddhist art

2.1. 佛教藝術傳統在南亞、中亞、與東亞的演變The evolution of Buddhist artistic traditions in South Asia, Central Asia and East Asia;

2.2. 佛教的藝術精神The spirit of Buddhist art;

- 佛教繪畫藝術Buddhist painting;

- 佛教音樂與舞蹈Buddhist music and dance;

- 佛教戲曲Buddhist traditional drama;

- 佛教雕塑藝術Buddhist sculpture;

- 佛教洞窟藝術Buddhist cave art;

- 佛教建築藝術(特別是:佛塔與廟宇) Buddhist architecture (particularly pagodas and temples) ;

- 佛教工藝傳統與科技的發展The development of Buddhist traditional arts and crafts;

- 佛教藝術在佛教跨地域與跨文化傳播歷程中的作用The role of Buddhist art in the process of Buddhism’s cross-regional and cross-cultural transmission;

同時,本論壇更鼓勵對兩大主題的會通研究,比如At the same time, the present forum especially welcomes comprehensive studies relating to both principal subjects, such as:

- 佛教藝術中的歐洲藝術的元素Elements of European art in Buddhist art;

- 歐洲文明對佛教藝術的影響The influence of European culture on Buddhist art;

- 佛教藝術對歐洲藝術的影響The influence of Buddhist art on European art;

- 藝術對融會歐洲文明與佛教文明的作用The role of art in integration of European and Buddhist civilizations;

- 基督教與佛教通過藝術的對話Dialogue through art between Christianity and Buddhism;

- 歐洲與佛教藝術傳統的相互借鑑與促進等Mutual learning and beneficial interactions between European and Buddhist artistic traditions, etc.

論壇計劃於2016年8月27-28日於西班牙馬德里召開(我們期待您8月26日到達,28日晚或29日離開)。誠請閣下撥冗參會,並發表論文。會議工作語言位英語與漢語,論文可以中文或漢文撰寫並發表。論文限於未發表者,並請參照以上所建議論題撰寫。懇請惠賜大作全璧;如囿於時日而未竟全功者,務請提供詳細之發言提綱(3,000-4,000字; 附PPT投影;除主題發言者外,發言時間限制在15分鐘)為盼,以期年內擴展成文,廣布四方,嘉惠中外士林。The forum is now being scheduled between August 27-28, 2016 (we expect your arrival on August 26 and you may leave in the evening of August 28 or anytime of the following day) in Madrid of Spain. We cordially invite your participation with an unpublished paper on a relevant topic pertinent to those as suggested above. A paper can be written either in English or Chinese, the two working languages for this Forum. A full-blown article will be greatly desired. In case this is impossible due to time constrains, a detailed summary (of 3,000-4,000 words) supplemented by a PPT file will do, in the hope that in the coming months the summary can be developed into a publishable paper to eth benefit of the whole academic society, both inside and outside China. Except for the keynote speeches, each presentation shall be limited to 15 minutes.

Committed Participants Include:

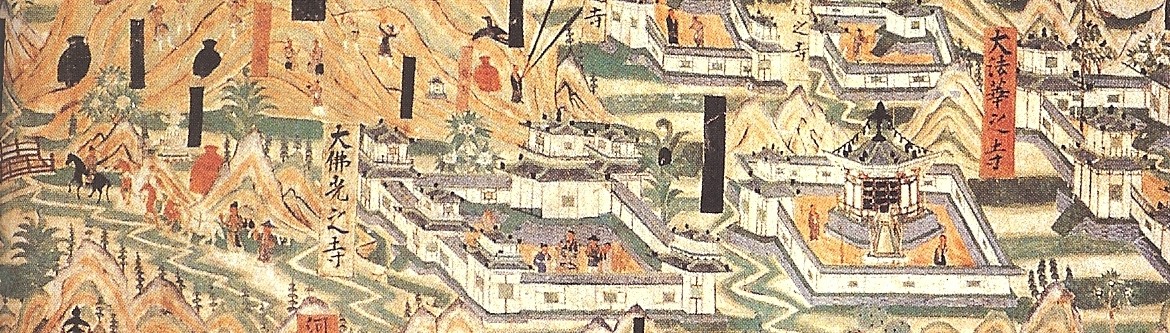

1. Susan Andrews 安素桑 (University of Mount Alison 加拿大聖阿裏森大學): “Material Culture and the Making of the Transnational Mount Wutai Cult: An exploration of the roles architecture, calligraphy, and statuary are playing in the contemporary Mount Wutai cults of Canada and China” 物質文化與跨國界五臺山信仰之型塑: 建築、書法、和雕像在當代加拿大和中國五臺山信仰中所扮演角色的探討;

This paper examines accounts of the establishment of a counterpart to Mount Wutai’s renowned Foguang Temple 佛光寺 in Ontario, Canada with records of the post-Cultural Revolution recreation of the Dasheng Zhulin Temple 大聖竹林寺 in Shanxi, China. Though born of very different circumstances, the connections between this pair of sites are substantial and growing. What ends does the remaking of Mount Wutai’s Tang architectural traditions serve in these contemporary contexts? How are statuary and calligraphy helping to sustain and develop the ties between the communities practicing at these distant hubs of devotion to Mañjuśrī? Pursuing answers to this pair of questions, the paper will illuminate the critical roles that architecture, calligraphy, and statuary are playing in the contemporary Mount Wutai cults of Canada and China.

2. Urs App (Ecole Française d’Extreme-Orient): “The first Western book about Buddha and Buddhism” 最初討論佛陀與佛教的西方著作;

The historiography of the discovery of our globe’s spiritual continents is very much lagging behind that of its physical counterparts. Europe’s encounter with Asia’s largest religion is a case in point. Whereas every child is familiar with figures such as Columbus, the protagonists of the Western discovery of Buddhism tend to be unknown even to scholars of Buddhism. Thus it comes as no surprise that the earliest Western book about Buddhism, Michel-Jean-François Ozeray’s Recherches sur Buddou ou Bouddou, instituteur religieux de l’Asie orientale (Paris: Brunot-Labbé, 1817), has hitherto received almost no attention in modern studies about the Western discovery of Buddhism.

In my contribution to the conference I will present and analyze Ozeray’s view of Buddhism and its founder, trace his main sources, and explain why Ozeray’s book deserves to be recognized as a valuable contribution to Western knowledge about Buddhism and its founder. Published just before the onset of university-based study of Buddhism and its texts, Ozeray relied heavily on artistic reproductions and reports by ambassadors and Western residents of Asian countries rather than on the letters, books, and arguments of missionaries. In spite of the evident flaws of Ozeray’s pioneering study, its overall vision of Buddhism as practised in Asia appears more congruent with modern field work than the majority of modern popular books on Buddhism.

3. Ian ASTLEY艾易安 (University of Edinburgh 英國愛丁堡大學): “It’s a thing thing: Japanese Buddhism’s arrival at British museums” 一種Thing Thing 遊戲: 日本佛教之進入英國博物館瑣談;

A larger than life-size Buddha now serves intermittently as a drinks table in the entrance hall at the National Museum of Scotland, before that it had for decades braved the Scottish elements in a stately garden – standing unperturbed as a token of a distant, exotic world. Such statues are not uncommon but collections, public and private, throughout the UK contain many items that reveal wide-ranging curiosity and perspicacity among their nineteenth-century collectors. Pamphlets for pilgrims from the foothills of Kōyasan and lists of items for an international exhibition by the Shingon sect are two examples from a motley set of items held at the Central Library in Edinburgh that show the mutual interest of West and East, interest that was at times mutual and complementary, at times evidence of conflicting or contradictory motivations. Other items, such as a gomadan set bought by Basil Hall Chamberlain for the British Museum, indicate the parlous state of Japanese Buddhism in the late nineteenth century, whilst priestly garments donated by Toki Hōryū 土宣法竜 show the desire of Japanese Buddhists to be considered as religious and civilized equals.

In this contribution I will seek to unravel what these artefacts can tell us about those crucial interactions, both in their contemporary context and in their import for today’s inter-cultural relations.

4. H. Barrett 巴瑞特 (SOAS, U. of London 英國倫敦大學): “Arthur Waley, Xu Zhimo, and the reception of Buddhist art in Europe: a neglected source” 亞瑟·韋利、徐志摩及歐洲對佛教藝術的接受: 一種被忽視的資料;

Although the Japanese writer Anesaki Masaharu姉崎正治 (1873-1949) is relatively well known, it would at first sight appear that his English-language treatise on Buddhist art in relation to Buddhist ideals (1915) was scarcely reviewed at all in English, save by Sir Reginald Fleming Johnston (1874-1938). There is however one anonymous review that has been generally overlooked, and it is the purpose of this paper to suggest that it was in fact written by Arthur Waley (1889-1966) with the help of Xu Zhimo (1897-1931).

5. Ester Bianchi 黃曉星 (Universita degli Studi di Perugia 義大利佩魯賈大學): “Chinese Cultural Association, Lay Temple, Buddhist Monastery and Nunnery: Recent transformations in rituals, teachings and practices of the Prato Puhuasi (Tuscany)” 從文化社團到居士林、從和尚廟到尼姑庵: 意大利托斯卡納大區普拉圖省普化寺近年在儀式、教義、與實踐上的轉變;

Puhuasi 普華寺 was founded in the city of Prato in 2007-2009 inside a former industrial building by a group of Chinese migrants living in Tuscany. During the first two years of activity, the temple worked as a cultural association in all similar to a lay Buddhist society (jushilin 居士林). In 2011, Xizhen 西真, a native from Wenzhou, was appointed abbot, but he only resided in the Puhuasi for important religious events, when hundreds (and even thousands) of Chinese devotees from all over Italy gathered in the temple. Since 2014, monks from Beijing Longquansi 龍泉寺 began to come to the temple on a regular basis. They devoted themselves to “normalizing” practices and rituals and also facilitated the entry of Puhuasi in the Union of Italian Buddhists. Finally, after the Dabei Longquansi 大悲龍泉寺 in Utrecht was opened in December of 2015, a group of six nuns from Fujian Jilesi 極樂寺 has taken up reseidence in Puhuasi, thus transforming the temple into a Buddhist nunnery. The present study aims to examine the evolution of the Puhuasi on a religious, social and institutional basis, taking into account both local aspects and relations, and links with Chinese institutions and society.

6. Marcus Bingenheimer 馬德偉 (Temple University 美國天普大學): “Foreign Visitors to Mount Putuo in the Late Qing” 清末年間普陀山的外國游客

Mount Putuo, a small island near Ningbo, that is held to be the abode of the Bodhisattva Guanyin, has for many centuries been one of the most popular sacred sites in China. Its many visitors have left numerous notes, poems and travelogues that describe the island from the 12th to the 18th century. These texts are collected in a series of temple gazetteers. For the last decades of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), however, there is a lack of Chinese accounts. It is around this time that foreigners start to visit Mount Putuo and the island is mentioned in quite a few travelogues by European and American travelers. Among them were: Charles Gutzlaff (visited 1833), W. Medhurst (1835), R. Fortune (1844), N. Rondot (7-8 October 1845), É. Huc (before 1854), A. Little (1875), T. Watters (before 1896), B. Laufer (1901), C. Kupfer (before 1904). These and others left impressionistic descriptions that nevertheless reveal a wealth of detail about the life on the island during a time for which few Chinese records exist. This presentation discusses the reasons behind this constellation of sources and summarizes the descriptions by foreign visitors to Mount Putuo in order to complement the record of the Putuo gazetteers.

7. Pia Brancaccio 龐琵雅 (Drexel University 義大利卓克索大學): “The Buddhist Caves in Western Deccan, India, between the 5th and 6th centuries” 5-6世紀印度西德干的佛教洞窟;

The lecture will examine the dynamics that led to the renaissance of Buddhist rock-cut architecture in Western Deccan between the 5th and 6th century. This was a transformative period in India as political, economic and religious traditions underwent important changes; from a global perspective, this was also a time of tremendous international engagement both across the Indian Ocean and the northwestern regions of the Subcontinent. The artistic and architectural evidence from caves like Ajanta and Aurangabad will be examined in a global perspective, connecting these sites to the Buddhist networks leading to the Northwest of the Indian Subcontinent and Central Asia, and to renewed Indian Ocean trade.

8. Daniela Campo 田水晶 (Universite Diderot 法國巴黎第七大學): “Buddhism’s Transmission to Europe: The Case of Foguangshan France” 佛教之傳入歐洲: 以法國佛光山道場爲例;

France has been the first European country where Foguangshan transnational Buddhist organization has established its branches. This paper retraces the difficult settling of Foguangshan in the Paris region through its successive stages since the beginning of the years 1990s, and inquires into the hindrances faced by the organization. The Fahua Chan temple, located in a multi-religious site in a suburb of Paris, hosts Foguangshan’s largest monastic community in Europe; since its opening in 2012, it has been selected as the European seat of the organization. By providing an overview of the distinctive features of this temple, I will consider the factors that have contributed to its integration in the local community, as well as the hurdles that still have to be overcome.

9. Nicoletta Celli 車霓珂 (Bologna University 義大利博洛尼亞大學): “Transferring and Translating Icons: New Thoughts on Early Buddhist Images in China” 傳播與翻譯佛教聖相: 關於中國早期佛教圖像的新想法;

The first representations of the Buddha in China (2nd-4th c.) consist of an array of mostly undated bronze statuettes portraying the Buddha seated in dhyānamudrā. Past scholarship has tended to consider these images to be the result of a straightforward, passive transmission from India, as though an object had been simply transported from one place to another and copied once it arrived at the final destination. The aim here is to show how, from the very earliest surviving works, the icon of the Enlightened One was on the contrary reinterpreted as part of a process that interacted with Chinese cultural conventions, rather than being a mere duplicate of Indian models. The argument centres on a detail that has so far been overlooked: even the very first of these specimens appear to invert the orthodox Indian position of the hands in the dhyānamudrā. The implications and significance of this variation are examined with reference to the visual imagery and cultural context of China.

10. Chen Jinhua陳金華 (University of British Columbia 加拿大英屬哥倫比亞大學): The “Biography” of a Buddha-Image: The Transformation of the Lore for a Stone-Image of Maitreya in Shicheng

This study investigates a sacred site centering on a stone image in southeastern China. With a focus on the ways in which legends and local histories represent the perceived sacrality of this sacred space, it aims to throw new light on the formation and transformation of the cult of the Shicheng image. Through a critical and comparative study of some of the fundamental legendary and semi-legendary components that constitute the complicated lore of this Buddhist sacred space, this study further endeavors to bring to the fore the political and social dynamisms—and sometime personal elements (like concerns for health problems that afflicted a powerful prince)—that propelled the carving and innovation of this colossal image.

11. CHEN Ming 陳明 (Peking University 北京大學):佛教譬喻故事“二鼠侵藤”的文本演變與圖像流傳: 從敦煌寫經中的典故談起 (The Evolution of Texts and Spread of Images of the Buddhist Story Called “Two Mice Eating Grass Roots”: A Discussion on Allusions in the Dunhuang Manuscripts)

敦煌出土的一些實用型文書(患文、佛文、邈真贊、齋文等)以及《法王經》中,在描述人生短暫、生命易逝時,常使用“四蛇毀篋”和“二鼠侵藤”兩個典故。本文以“二鼠侵藤”這一譬喻爲研究對像,追溯該譬喻的源頭,即該譬喻在印度大史詩《摩呵婆羅多》以及漢譯佛經《佛說譬喻經》、《賓頭盧突羅闍爲優陀延王說法經》、《衆經撰雜譬喻》等文獻中的使用及其所蘊含的譬喻意義,梳理中古佛教注述(《注維摩詰經》、《維摩經義疏》、《翻譯名義集》等)對該譬喻的解釋與認知,幷考察該譬喻在日本佛教詩文中的引用情况,尤其是探尋該譬喻在西亞民間故事集(Kalila wa Dimna和’iyar-i Danish of Abu al-Fazl)以及歐洲文獻(Book of Barlaam and Joasaph和《托爾斯泰文集》等)中的流傳情况,分析該譬喻在不同時空的宗教與文化語境中所起的訓誡作用,尤其是比較該譬喻的涵義的异同及其演變。此外,本文在搜集該譬喻故事的多幅圖像史料的基礎上,分析該譬喻文本含義的演變與圖像的不同描繪,爲佛教文學的圖像與文本的關係研究提供一個實證性的例子。

12. Deng Qiyao 鄧啓耀 (Sun Yat-sen University中山大學): 天衣無界: 佛教造像服飾研究 (The Heavenly Cloths Having no Boundaries: A Study on the Clothes of Buddhist Statues);

從早期佛教造像服飾對古希臘羅馬雕像服飾的借鑒,已經可以窺見歐亞文化交流的端倪。這一空間脉像,應該與古代絲綢之路或歐亞走廊的族群互動有直接關係。與佛簡潔的披裹式袈裟相對應的,是裸體而繁飾的菩薩和諸天,衣著扮相頗富南亞風韵。在時間的流痕中,菩薩不知不覺從男身轉換爲女身,裸露的身體漸漸包裹嚴實;諸天也披挂起漢式甲胄,穿服上廣袖深衣。而在佛教傳入中國不同地域不同族群的時候,漢傳、藏傳、南傳各宗,又在在地化的文化適應中不斷變服從俗,呈現了千姿百態的民族化服飾風格。

13. Max Deeg 寧梵夫 (University of Cardiff 英國卡迪夫大學/Max-Weber-Kolleg, University of Erfurt 德國愛爾福特大學): “The historical turn: How Chinese Buddhist travelogues changed Western perception of Buddhism” 歷史性的轉換: 中國佛教徒的游記如何改變了西方對佛教的感知;

Information about Buddhism was scarce and vague at best in the West until the beginning of the 19th century. The first orientalists studying Indian sources had to rely on Hindu texts written in Sanskrit (e.g. Purāṇas) which portrayed the Buddha as an avatāra of the Hindu god Viṣṇu. The situation changed with the discovery of the Pāli texts from Śrī Laṅkā through scholars like George Turnour and the decipherment of the Aśokan inscriptions through James Princeps by which the historical dimension of the religion became evident. The final confirmation of the historicity of the Buddha and the religion founded by him was taken, however, from the records of Chinese Buddhist travellers (Faxian, Xuanzang, Yijing) who had visited the major sacred places of Buddhism in India and collected other information about the history of the religion. This paper will discuss the first Western translations of these travelogues and their reception in the scholarly discourse of the period and will suggest that the historical turn to which it led had a strong impact on the study and reception of Buddhism –– in a way the start of Buddhist Studies as a discipline.

14. Francisco Diez de Velasco 狄十鴉 (Universidad de La Laguna 西班牙拉古納大學): “The visibilization of the new Buddhist artistic heritage in Spain: examples of artistic hybridization in Vajrayana retreat centers” 西班牙新佛教藝術傳統的可視化: 以金剛乘佛教靜修中心的藝術混合為例;

The presence of Buddhist worship centres in Spain is recent. The first were established from 1977, in the new context of religious freedom brought about by democratization, one of the main elements was to guarantee the free exercise of religion after decades of religious exclusivity that prevented the development of Buddhism beyond few individual options. In the later years it has emerged a new Buddhist artistic that manifests in a very interesting way in the centers which follow Tibetan Buddhism. In this paper a number of these centres are reviewed in order to visibilize the features and diversity of the new Spanish Buddhist artistic heritage that has chosen two main ways of expression. In some cases it has been chosen to import Asian constructive and artistic models. We found monasteries and urban centres of worship where the aesthetic impact with respect to Spanish artistic heritage is remarkable. A good example is found in the monastery Dag Shang Kagyu (Panillo, Huesca). In other cases are combined Oriental elements with local elements, producing an interesting hybridization. A good example is offered by the monastery Sakya Tashi Ling (El Garraf, Barcelona), Karma Guen (Vélez-Málaga) or O Sel Ling (Bubión, Granada). In other cases the architectural and artistic proposals opt for modern buildings where Buddhist artistic elements are very subtle. An example is the Sakya Foundation (Pedreguer, Alicante) and an interesting new model is proposed by the Kadampa Hotel (Alhaurín, Málaga).

In this paper these centres will be reviewed in order to visibilize the features and diversity of the new Spanish Buddhist artistic heritage. The photographic material generated in the research project Budismo en España/Buddhism in Spain (http://fradive.webs.ull.es/

15. Steffen Doell 道諦芬 (University of Hamburg 德國漢堡大學): “Tang-Tokugawa Alliances and Song-Kamakura continua: Writing the History of Chan/Zen Buddhism” 唐朝-德川幕府的聯盟與宋朝-鐮倉時代的連續: 論禪宗的歷史書寫;

In stark contrast to the traditionalist narrative which focuses on Chan Buddhism’s patriarchy during the Tang dynasty, ongoing research into the history of Chan/Zen has resulted in a re-evaluation of its heretofore disregarded areas and periods. Interestingly enough, research on Japanese Zen, however, by and large tends to stay focused on the same old “usual suspects:” Dōgen and Eisai, Hakuin and the Ōtōkan lineage. Important though these may be, large desiderata such as metropolitan Zen during the Kamakura and Muromachi periods are left mostly unexplored. Reasons for this well-established monophthalmia, this talk will suggest, lie with modern sectarian considerations: Zen studies have developed out of a deep-rooted affiliation with modern Zen practice and produced a canonical conservatism that generally prevents us from investigating Zen in its most vibrant historical forms.

16. Bernard Faure 佛爾 (Columbia University 美國哥倫比亞大學): “The Life of the Buddha: Road Taken and not taken” 佛陀生平: 路逕之擇取與放棄;

Since the famous controversy that opposed Émile Senart to Hermann Oldenberg (1854-1920) (1847-1928), many scholars, following Alfred Foucher’s example, have attempted to find a middle way between history and mythology. That middle way has proved to be an elusive goal, however, not to say a dead end. Barring any major new archeological finding, the Life of the Buddha seems condemned to remain a hagiographic tale, woven out of myth and legend. Even so-called “biographies” of the Buddha have actually only created another myth, that of the ‘historical’ Buddha — a variant of which is the ‘scientific’ Buddha recently discussed by Donald Lopez. Accordingly, this paper, after discussing the methodological biases of the Western scholarship, shifts the focus from the ‘historical’ to the ‘paradigmatic’ Buddha, in an attempt to do justice to the wealth and creativity of the Buddhist (Indian and East Asian) traditions.

17. Anna Filigenzi 菲利真齊 (Universita degli studi di Napoli L’Orientale 義大利那不勒斯東方大學): “The Buddhist art of Gandhara: Stereotypes and Misunderstandings about East -West Encounters” 犍陀羅佛教藝術: 關於東西方邂逅的定見與誤解;

Since its discovery in the mid 19th century, the art of Gandhara has attracted wide interest among scholars and collectors because of its Hellenistic features. While in India the approach to Gandharan art mingled with identity constructions in the colonial and post-colonial period and was somehow marginalised from “true Indian” art history, in the Western world the perception of this artistic phenomenon was instead biased by a sense of familiarity, which made (and still makes) people think that the interpretive keys are within easy reach. The models and styles of Greek and Roman classicism we recognize in Gandharan art as well as the linear progression of its peculiar mode of visual narration paradoxically represent the most serious limits to our understanding. Studies in Gandharan art are too often confined within purely descriptive analyses of iconographic themes lacking contextual interpretation, or attempts at defining chronologies based on debatable stylistic classifications.

Thus, we see Dioscuri, city goddesses, fauni and satyrs taking part in visual discourses that will remain dumb for us until we realize that Gandharan art is not a sum of juxtaposed parts but the distinctive idiom of a specific cultural context, which can only be explored and understood through a more holistic approach.

18. Imre Galambos 高奕叡 (University of Cambridge 英國劍橋大學): “Pictorial representations of the Sudana sutra from northwestern China” 中國西北對《須達經》的圖形化再現;

The Vessantara (Skt. Viśvantara) jātaka is one of the most popular jātakas in the Buddhist tradition and this is equally true for Central and East Asia. Since the early medieval period, the story itself has been translated—from presumably Indic sources—into a number of northern languages, including Tocharian, Chinese, Sogdian and Tibetan. Fragments of these translations have been found at various Silk Road sites in the north-western region of China, including Dunhuang and Kucha. Along these manuscripts, scenes from the jātaka appear in cave murals in Dunhuang and other sites, corroborating the popularity of the story along the Silk Road. This paper will address the relationship between the Chinese version of the jātaka (called Sudana sūtra) and its visual representations at cave sites. My focus is on to what extent were the images based on the Chinese text and whether the comparison is able to help us in dating the translation.

19. Gong Jun 龔隽 (Sun Yat-sen University 中山大學): 李提摩太與英譯《大乘起信論》 Timothy Richard and the Dasheng qixin lun;

本文主要討論十九世紀末與二十世紀初,來華活動的重要傳教士李提摩太是如何通過英譯《大乘起信論》,而有策略性地把大乘佛教基督教化,幷回應歐洲學界所發生的佛教與基督教的論辯。論文從如下幾個方面開展:1、把李提摩太翻譯《起信論》作爲一次思想史的事件,放置在具體的思想與歷史脉絡中去進行闡明,提出李提摩太翻譯《起信論》一方面是試圖從該論中尋找基督教在華傳教的新的思想啓示,同時也把他的翻譯看作是十九世紀西方的東方學內部問題的另一種發展。2、論文闡析了李提摩太思想中有關“大乘”與“小乘”的特殊用意,分析了他有關大乘觀念的論述中是如何通過基督教式佛典的譯解,建構“佛教大乘西源”說,以表明基督教思想對于佛教的優先性。3、論文具體討論了李提摩太英譯中的“洋格義”,即以例證說明他如何以西方基督教思想的觀念來譯解《起信論》。At the turn of the twentieth century, Timothy Richard (1845-1919), a Welsh Baptist missionary to China, translated the Dasheng qixin lun 大乘起信論 (Treatise on the awakening of faith according to the Mahāyāna) into English. Taking this translation activity as the subject of study, this paper understands it to be a strategic effort to evangelize Mahāyāna as well as a response to debates regarding Buddhism and Christianity in the European academic world. This paper evolves as follows. First, it takes Richard’s effort as an intellectual history event. Under the intellectual and historical context at the time, it is understood to have aimed at finding inspirations for Christian missionary activities in China, and represented a new progress in the orientalism of the West in the nineteenth century. It then moves forward to analyze special motivations behind the translator’s discussion about dasheng 大乘 (Mahāyāna) and xiaosheng 小乘 (Hināyāna). Of particular interest here is how he granted Christianity supremacy over Buddhism by inventing a theory that “Mahāyāna originated from the West”, which was in turn achieved through translating and interpreting Buddhist texts in the Christian ways. Finally, this paper carries out a detailed discussion of the western geyi 格義 (meaning-matching). With examples, it illustrates how Timothy Richard interpreted the Qixin lun with concepts deriving from Christianity in the West.

20. Amanda Goodman 葛玫 (University of Toronto 加拿大多倫多大學): “The Five-Buddha Maṇḍalas of Tenth-Century Dunhuang” 十世紀敦煌的五佛曼陀羅;

This paper traces the five-buddha maṇḍala motif across media at Dunhuang during the final decades of the tenth century. Specifically, it traces the deployment of a powerful assembly of Buddhist deities, headed by Vairocana Buddha 毗盧遮那佛 (alternately identified as Mahāvairocana Buddha 大毗盧遮那佛 and Rocana Buddha 盧捨那佛), across ritual genres (maṇḍala rites 壇法, contemplation practices 觀法) and visual forms (monochrome ink sketches, portable paintings) at the site. Using textual and visual analysis, in combination with socio-historical evidence, the paper argues that these recovered Dunhuang sources, some of which are dated, and all of which appear to have been regionally produced, represent the material remains of a local esoteric Buddhist dispensation that served to bolster the ruling Cao 曹 family during the late Guiyijun 歸義軍 period – a time and place understood to be under the direct domain of five specific buddhas, again, headed by Vairocana, and a unique maṇḍala assembly.

21. Phyllis Granoff 葛然諾 (Yale University 美國耶魯大學): “Reading Medieval Buddhist Manuscripts: Thoughts on Text and Image” 中古佛教寫本一讀:對文本和圖像的一些思考;

This paper explores the very different relationships that exist between text and image in Buddhist palm leaf manuscripts. It begins with the famous manuscript of the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā in the Cambridge Library, which it takes as an example of a manuscript in which the written words and the painted images in effect constitute two different and independent texts. A second manuscript, of the Gaṇḍavyūha, folios of which are in the Cleveland Museum, shares with the Cambridge Prajñāpāramitā the lack of any direct connection between written word and picture, with few exceptions. But there are other cases, often missed by scholars, in which images do carefully reflect the written text. This is the case with a Pañcarakṣā manuscript now also in Cleveland, where, it will be argued, close attention to the text allows us to see how carefully the images give visual form to what the text describes. This manuscript also offers a guide as to the restricted circumstances in which it might be useful to look to other closely related texts to enrich our understanding of manuscript illustrations.

22. Imre Hamar 郝清新 (Eötvös Lorand University 匈牙利羅蘭大學): “The Khotanese Ox-head Mountain paintings in Dunhuang” 敦煌的于闐牛頭山繪畫;

The Ox-head mountain is one of the Khotanese auspicious images that can be seen in several Dunhuang caves. The Ox-head mountain is regarded as sacred place of Buddhism as Buddha is said to have preached his doctrine there. Chinese interpreters of the Buddhāvataṃsaka-sūtra identify this mountain as one of the abodes where bodhisattvas stay, and Xuanzang also recorded legends associated with this mountain in his Record of Western Regions. Due to the family relations between the Khotanese royal court and the governors of Dunhuang the images of Khotanese king, princes and auspicious imaged were painted in Dunhuang caves. In this paper we are going to discuss the iconographical significance of the Ox-head mountain images in Dunhuang.

23. HAN Tingjie韓廷傑 (Institute of World Religions Chinese Academy of Social Sciences中國社會科學院宗教研究所):中國佛教洞窟藝術(Chinese Buddhist Arts of stone caves)

石窟,又稱為石室、窟院等。 中國的石窟開鑿始於西元三世紀,盛行於五至八世紀,十六世紀後基本結束。

中國現存最古老的石窟,是新疆克孜爾石窟。始鑿於西元三世紀末四世紀初,東西長達兩公里,規模之大,僅次於敦煌莫高窟。克孜爾石窟有洞窟236個,從其壁畫來看,顯然受古印度犍陀羅藝術的影響, 西元五、六世紀 出現中國風格,七至八世紀逐漸衰落。

在中國影響力較大的有四大石窟,即敦煌莫高窟、雲岡石窟、龍門石窟和麥積山石窟。甘肅省的敦煌莫高窟是當今世界上現存規模最大,保存最完好的佛教藝術寶庫。現存北魏至元的洞窟735個,“藏經洞”的學術價值最高。山西省的雲岡石窟開鑿於北魏興安二年(西元453年),大部分完成於北魏遷都洛陽之前(西元494年),造像工程一直延續到正光年間(西元520-525年)。最古的石窟是第16窟至20窟,俗稱曇曜五窟。雲岡石窟現存主要洞窟45個,大小窟龕254個,造像51000多尊,代表了西元5至6世紀世界美術雕刻的最高水準。河南省的龍門石窟始鑿於魏孝文帝遷都洛陽之際(西元493年),歷經東魏、西魏、北齊、隋、唐、五代、宋等400多年的營造,從而形成南北長達一公里的石窟藝術寶庫。現存窟龕2300多個,雕像11萬餘尊,碑刻題記2800多塊,十分壯觀。麥積山石窟始建於後秦時期(386-417年),麥積山的石質不適於雕刻,所以這裏的造像都是泥塑的,所以有 “塑像館”之稱。計共保存有從西元四世紀到十九世紀約一千四、五百年間的泥塑、石雕7200多件,壁畫1300多平方米。其中十六國後期(後秦)和北朝(北魏、西魏和北周)時期的作品占絕大多數。

24. Hong Xiuping 洪修平 (Nanjing University 南京大學): “The Role Played by the 19th Century European Scholars of Religious Studies in the Translation and Spread of Buddhist Texts: A Case Study of Max Müller” 論十九世紀歐洲宗教學家對佛經的翻譯與傳播——以麥克斯繆勒為例

宗教學作為一門對人類擁有的各種宗教現象進行科學歸納與綜合研究的學科,能夠在十九世紀的歐洲社會中逐漸興起,原因是多方面的,其中與十九世紀歐洲宗教學家對東方宗教文化所抱有的特殊熱情,努力擺脫歐洲傳統的基督教神學束縛,通過學習東方語言,翻譯東方宗教經典,以比較宗教學為方法,期望對紛繁複雜的宗教現象進行“不偏不倚”的客觀研究有著密切關係。其中最有代表性的人物是英國牛津大學語言學教授麥克斯·繆勒(F.Max Muller,1823~1900),他通過對佛經的翻譯,推動了佛教在歐洲的傳播,加深了歐洲人對佛教的認識,也為宗教學的創立提供了豐富的文化資源。

在麥克斯·繆勒看來,語言、民族與宗教存在著一種天然的聯繫。如果我們瞭解早期宗教語言的情況,那麼就知道語言科學的分類也能適用於宗教科學。如果不同民族語言之間確實有系譜關係,那麼,也可以通過系譜關係把全世界的宗教聯繫在一起進行研究。於是,他以比較語言學(comparative philology)為模型來建構比較宗教學,由此也展示了佛教在世界宗教中的地位。從1853年開始,麥克斯·繆勒撰寫一系列有關東方宗教的著作,其中包括1862年出版的《佛教》。

麥克斯·繆勒對佛經的翻譯與傳播的貢獻是:第一,從宗教學的創立來看,他通過將佛教與基督教、猶太教、婆羅門教、古代波斯的瑣羅亞斯德教等進行比較研究,第一次提出“宗教學”這個概念,創立了“宗教學”這門學科。第二,從佛教在歐洲的傳播來看,雖然他推動的佛經翻譯以及對佛教的研究尚處於附屬於東方學、印度學的研究階段,但卻為西方語境之“他者”的佛教進入歐洲世界打開了大門,在客觀上推動了佛教在歐洲的傳播。第三,從歐洲的佛學研究來看,他採用比較語言學等方法,在將梵語佛經譯成英語的過程中,注重對名詞概念的詞源性考證,重視通過佛教與其它宗教的橫向比較研究,來展現對佛教文化特質的認識,由此形成了歐洲佛教研究中的文獻與哲學並重的學術路向。從研究立場和研究方法上看,麥克斯·繆勒期望能夠超越基督教的文化傳統與西方學術的知識背景,努力以學術中立的姿態去解讀東方佛教之本義,這一良好的學術志向對推動歐洲現代佛學研究展開產生深遠的影響。

25. Andreas Janousch 楊德 (Universidad Autonoma de Madrid 西班牙馬德裏自治大學): “A Brief History of the Study of Buddhism in Spain” 西班牙佛教研究簡史;

26. Ji Zhe汲喆 (Institut national des langues et civilisations orientales 法國國立東方語言文化學院): 全球化與漢傳佛教在法國的傳播 (Globalization and the Spread of Chinese Buddhism in France)

漢傳佛教作爲一種被實踐的宗教,直到二十世紀末才在法國才逐步形成規模。依據歷史檔案、相關研究和田野調查,本文回顧了漢傳佛教在法國的傳播過程,考察了法國華人移民的結構,幷分析了佛教在法國華人社區得以建構的三種模式。這三種模式分別優先使用了一種全球化的媒介,即同鄉群體、跨國組織和網路通訊技術。作者認爲,宗教的全球化是一個多層的跨界過程,在這一過程中,共同體、組織和個體共同改變了宗教與社會—地理空間的聯繫。移民佛教的僧—俗關係和宗教權威的合法化方式與傳統佛教都有所不同,其話語和實踐也同時受到中、法社會與政治條件的影響。

27. Jiang Hainu 蔣海怒 (Zhejiang Sci-Tech University 浙江理工大學): 藝術的神話: 對鈴木和海瑞格禪視角的一個評論 (Mythology of Art: A Critique of Suzuki and Herrigel’s Zen Perspective)

在鈴木大拙(D. T. Suzuki)和海瑞格(Eugen Herrigel)的撰述中,箭藝和茶道等日本藝術被詮釋為禪的超越精神的表達。這種突破性視角其實是借力於基督教神秘主義傳統的復興,並經由歐美非理性哲學的運思清晰地表達出來的。然而,它的神性內核,它的秘密起源,它技藝的卻非操作性的旨要卻使其更接近於神話敘事。自然,這種禪藝術的解釋框架並未取得普遍認同。當我們返回到其誕生的政治文化語境時,不難發現這種話語的“鏡像特征”,它的懸隔於明治前後和東西方之間的“邊界焦慮”和文化的“身份認同”困惑,這種模糊不清的“自我意識”也使其在不斷被質疑中陷入了存在危機。即便如此,作為對東方藝術現代的創造性詮釋嘗試,《禪與日本文化》(Zen and Japanese Culture)和《箭藝中的禪》(Zen in the Art of Archery)依然會引起人們無盡的話題。

28. George Keyworth 紀强 (University of Saskatchewan 加拿大薩斯喀徹溫大學): “On the ‘Shintō’s Statues of Matsuo Shrine: Tendai Buddhist Rituals, Iconography, and Veneration in Japan and China” 關于松尾神社的“神道”雕像: 日本與中國的天臺宗佛教的儀式,影像學和崇拜;

One of the oldest and most revered shrines in Japan, Matsuo shrine is far less well known than Ise 伊勢, Kasuga 春, Fushimi Inari 伏見稲荷, Hachiman 八幡, or the Kamo 加茂 shrines. Not only has a mostly hand-copied, twelfth-century Buddhist canon survived from Matsuo shrine, but there are also twenty-one statues preserved today onsite within the Shinzōkan 神像館. Three of these statues are especially well known because they are among the oldest “Shintō” statues from the early Heian period (794-1185). Another eighteen twelfth-century statues survive from the among the seven sub- and main-shrines that once formed the premodern Matsuo shrine-temple complex (jingūji 神宮寺) in western Kyoto. In this paper I investigate three aspects of the statues of Matsuo shrine. First, I examine how mishōtai 御正体 (lit. revered true bodies) are understood by scholars of indigenous Japanese religion—“Shintō”—and by historians of East Asian Buddhism, often within the rubric of so-called Shintō-Buddhist “syncretism” (shinbutsu shūgō 神仏習合). I am particularly interested in how Japanese and European scholars once utilized methodologies that effectively obscured these objects of material culture from consideration. Next, I explore origin tales (engi 縁起) about several of these statues which connect them to Enchin 圓珍 (814-891) and the powerful medieval Tendai 天台宗 monasteries of Enryakuji 延暦寺 and Miidera 三井寺 (Onjōji 園城寺). It very well may be that some of the Matsuo statues reflect continental, ninth-century Buddhist and Daoist ritual systems supported by the medieval Japanese state. Finally, I present evidence from several colophons to scriptures within the Matsuo shrine Buddhist canon which show that these statues played a pivotal role in a separate Matsuo shrine propagation process of reduplication throughout Japan during the fourteenth through eighteenth centuries. These statues are certainly Buddhist, as much as they are “Shintō,” and this paper also addresses the relationship between Chinese and Japanese gods venerated with so-called “esoteric” Buddhist rituals.

29. Kim Jongmyung 金鐘明 (Academy of Korean Studies 韓國學中央研究院): “Korea’s Possible Contribution to the Printing Technology in Europe” 韓國對歐洲印刷術的可能貢獻;

This paper aims to examine Korea’s possible contribution to the printing technology in Europe. Published in 1377, seventy-eight years earlier than the 42-line Bible by Johann Gutenberg (c. 1398-1468), the Korean Zen text, Chikchi simch’e yojŏl 直指心體要節 (The Essential Passages Directly Pointing at the Essence of the Mind), is known as the oldest extant metal type printing in the world and is now on the UNESCO Memory of the World list. Scholars have suggested a necessity of comparative studies of the possible exchanges of the printing technology between the East and the West. However, their suggestions have been in passing phrases and no substantial research on the subject has been conducted thus far. Along with ink, paper is an essential element for printing and it was invented in China in the second century. A production method of paper was transmitted to Europe in the fourteenth century. The woodblock printing technology was also initiated in China in the third century and it was known to Europe in the twelfth century. Korea is regarded as the first country in the world that invented the metal type printing technology and its date was at least in the thirteenth century. Korean metal types are also presumed to have been transmitted to European cities, including Mainz, the native place of Gutenberg. Considering the paucity of relevant materials, this research will examine the subject matter tracking the history of transmission of paper, ink, and the printing technology to Europe. This paper hopes to contribute to broadening scholarly horizons for a more in-depth research on the mutual exchanges of the printing technology between the two hemispheres.

30. Christina Laffin 賴可馨 (University of British Columbia): “Literary depictions of medieval nunhood” 對中古比丘尼群體的文學描述;

This paper will examine the role of nunhood in the lives of medieval women, focusing on representations found within literature. I will consider how the option of becoming a nun may have formed part of a woman’s life cycle by looking at cases from East Asian and European history in a comparative context. What secular and religious motivations may have impacted a decision to take dedicate oneself to religious practice, whether this meant entering a convent, taking vows, going into reclusion, or carrying on a relatively active secular life? How does this differ across religious traditions? Drawing from a wealth of new scholarship on nuns in East Asia we will consider what parallels can be drawn across practices and traditions.

31. Lai Wen-Ying 賴文英(Fo Guang Univesity 臺灣佛光大學): 佛教美術與基督教美術的會通 (Combining Buddhist and Christian arts and Understanding them thoroughly)

宗教被視為藝術起源的一項重要元素,宗教藝術除了表現於外的風格、技法等藝術性之外,不可忽略的是其內在所傳達宗教神聖意涵的功能性。佛教與基督教在發展初期都曾以隱喻、象徵的手法來表現其信仰之存在,符號或象徵物被賦予特定的神聖意義,以期達到宣教的目的,即使是形象化之後的佛像或聖像,仍然保有其宗教上的深厚意蘊。本文著眼在佛教與基督教透過藝術形式所體現的宗教之神聖性,藉由對建築、繪畫、雕刻等美術作品的觀察,檢視藝術在宗教發展過程中所扮演的角色,並進一步思考其內在的共通語言。

32. LAI Yueshan 賴嶽山(Sun Yat-sen University 中山大學): 布教、政治與學術的碰撞——1928-1929年”民國政府-太虛法師“第一次面向西方的佛教輸出 (A Clash between Missionary Activities, Politics, and Scholarship: The First Output of Buddhism to the West, Initiated by the Nationalist Government and Master Taixu between 1928 and 1929)

1928年8月至1929年4月,中國佛教的改革派領袖太虛法師(1890-1947)在“國民政府-蔣介石”的支持下,第一次希望以“對等”的方式,遠赴歐美,輸出佛教。該事件的成因、目的、與“現代國家”的關係、乃至短期功德和长期效用,向來眾說紛紜、毀譽參半,也值得鉤沉索隱。作者首先在方法上甄別四類材料——田野調查、國家檔案、宗派自述、輿論反響——的類型和特質,再通過比較分析,嘗試理解以下幾個要素:(1)在“現代國家”和國際(宗教)外交的背景下,將此事件定性為中國佛教對當時國際秩序、宗教秩序的一次“主動的反擊”與“試探性重構”;(2)又因太虛戲劇性的個人特質,使得其在學理上無法與西方精英知識界進行有效的交流,但其精神遺產、以及組建佛教國際組織的動議,卻在幾十年後逐漸變為現實,這本質上可稱為“實踐佛教獲得了生存上的勝利”;(3)然而,問題也恰恰在此,積極介入世俗政治的佛教,其工具性的表象或“方便”,可能永久地倒轉為本質和基礎;(4)以上幾點分析最終簡化為一個新的追問——近現代中國傳統佛教的“本來面目”如何在西方現代“國家”與“宗教”的規定中獲得相應的合法性?

33. Jeong-hee Lee-Kalisch 李靜姬 (Free University of Berlin 德國柏林自由大學): “The Transmission of Ornaments in Buddhist Art” 佛教藝術中裝飾物件的傳播;

Beyond iconographic dimensions the ornaments in Buddhist art become apparent through the depicted figures and their fashion, as well as other pictorial, architectural elements including patterns and motifs. Early Buddhist texts and local chronicles provide information on neither its origin nor its meaning; therefore we often have to deal with upper and lower very clichéd connotation. In this paper, the aesthetical and art historical value of the ornaments until the ninth century A.D., based on the selected example, as a phenomenon of cultural transmission and intertwinement is to be discussed with regard to the cultural originality and diversity among the cultural traditions of the “West” and “East”. It reveals the essential process of how “foreign” images were transmitted and reproduced at the “local” (Central and East Asia) religious space, at the same time, how implicated images had functioned as a medium of communication during the transmission.

34. Li Chongfeng 李崇峰 (Peking University 北京大學): 石窟壁畫與天竺遺法 (Wall-paintings of the Cave-temples and Shading Methods of Hinduka)

中土傳統上稱佛教爲像(像)教。李周翰注《文選》時明確釋義:“‘像教’,謂爲形像以教人也。”因此,佛教繪畫與雕塑是佛法傳播的重要媒介與手段。 石窟寺既是地面寺院 (free-standing monastery and temple)的石化形式 (petrified form),也是重要的世界文化遺產。在南亞、中亞和中國佛教石窟寺壁畫的創作中,繪畫技法應用最廣泛者應屬色彩漸變,即“天竺遺法”。印度阿旃陀(Ajaṇṭā)和巴格(Bagh)石窟、斯裏蘭卡獅子岩(Sigiriya)壁畫、阿富汗巴米楊(Bāmiyān)石窟和中國新疆克孜爾(Kizil)及敦煌莫高窟(Mogao Caves)的早期壁畫,創作時間主要當在五至七世紀,皆采用相似的暈染方法,即天竺凹凸法,以表現所畫物像的立體感,只是各地側重點稍有不同。

這種繪畫技法在印度《畫經》(Citrasūtra)中多有記載,疑主要用于壁畫的創作,使熟睡人與長逝者彼此神態可辨,形體“能分低與高”。尤爲重要的是,《畫經》特別記載只有完全采用暈染法、具有立體感的畫作才能稱作上品。南亞、中亞和中國石窟壁畫中采用的“凹凸法”,以同一色的不同色度呈現出不同色階,以由淺入深或深淺漸變的暈染方式形成明暗關係,長于表現肌膚的立體感;畫面莊重嚴謹,人體渾厚飽滿,色彩濃郁厚重。

中國早期壁畫采納天竺凹凸法,或與北齊魏收所記“凡宮塔制度猶依天竺舊狀而重構之”的理念有關。至于隋唐時期的中土繪畫,據張彥遠《歷代名畫記》卷三《記兩京外州寺觀畫壁》,佛教題材及內容仍占絕對優勢。尉遲乙僧所畫凹凸花,可謂天竺凹凸法之延續;而吳道子之再創新,使中國佛教壁畫的寫實風格更趨完善。

35. Li Jingjie 李靜傑 (Tsing-hua University 清華大學): 論宋代石窟造像反映的佛教思潮 (Buddhist Thoughts as Reflected in Stone Caves of the Song Dynasty);

在陝西北部及重慶大足和四川安岳,集中分布著規模化宋代石窟造像,如實地反映了當時的佛教思潮。其一,孝道思想受到前所未有的重視。陝北北宋諸多洞窟浮雕模式化涅盤圖像,以及大足寶頂山南宋摩崖石刻釋迦佛入涅盤巨像,重心在于摩耶夫人登場,表述了經典所雲佛爲後世不孝衆生說法的意圖。同寶頂山南宋浮雕兩對父母恩重經變和大方便佛報恩經變,强調了父母恩重和知恩報恩,孝道乃至成爲菩薩行的重要一環。其二,菩薩行思想再度流行幷加以强化。安岳石羊場與大足寶頂山三鋪南宋浮雕柳本尊十煉圖像,將法華經燒煉供養和華嚴經割捨布施結合起來,體現了由菩薩行而成就法身思想。其三,陝北北宋石窟諸多主尊三佛圖像反映的往生淨土,以及大足石刻兩宋儒釋道組合圖像反映的三教融合思想,亦構成宋代佛教思潮的重要內容。

36. Beatrix Mecsi 墨思璧 (Eötvös Lorand University 匈牙利羅蘭大學): “The Arhats and Their Legacy in the Visual Arts of East Asia” 東亞視覺藝術中的阿羅漢及其遺産;

In East Asian art we often encounter the representation of arhats (skt. those who are worthy), a type of Buddhist saintly figure, in groups of 16, 18 or 500. In my presentation, I focus on the visual representations of arhats, and show how the concept, the grouping, the form and style of their representation has changed in China, Korea and Japan. I will point out some particular themes and their relationship with the arhat representations, such as representations of Bodhidharma, the first Chan patriarch, and Pindola Bharadvaja, one of the disciples of Sakyamuni Buddha, who was believed at the turn of the 20th century to have served as the background idea for the origin of the Wandering Jew mythology in Europe.

37. Carmen Meinert 梅開夢 (Ruhr-Universität Bochum 德國波鴻魯爾大學): “Reading Tantric Buddhist images in Pre-modern Central Asia through Texts” 通過文本解讀前現代中亞地區的密宗圖像;

During the pre-modern spread of Buddhism in Central Asia Buddhist visual art (may it be in form of cave paintings or paintings on cloth) was crucial in Buddhism’s cross-regional and cross-cultural transmission. However, I would argue that such pieces of Buddhist art need to be read through texts ––– at least in those cases where we have matching manuscript findings as well. I will exemplify my argument through the case of the transmission of Tantric Buddhism between roughly the 10th and 12th century in Eastern Central Asia.

38. Miao Lihui 苗利輝 (Xinjiang Institute for the Study of Kuci 新疆龜茲研究院): 龜茲佛教淨土藝術 (Arts related to the Pure Land in Kuci Buddhism)

佛教淨土藝術,是表現佛教中淨土信仰的藝術類型。佛教淨土中的淨土與穢土相對而言,是指有佛菩薩存在的莊嚴清淨國土。龜茲佛教中的淨土依其形成的內容和反映的思想可分爲彌勒淨土、西方淨土、東方淨土和華嚴淨土。龜茲地區淨土思想的傳入很早,主要爲彌勒上生淨土信仰,藝術風格爲龜茲風格。唐代,

39. Ulrike Middendorf 梅道芬 (University of Heidelberg 德國海德堡大學): “The Vernacular Reconsidered: A Second Look at Zürcher’s Scriptural Idiom in Earliest Buddhist Translations”; 重新思考方言: 再議許理和對最早期佛教翻譯中成語的看法

40. Antonello Palumbo 白安敦 (SOAS, U. of London 英國倫敦大學): “Jean-Pierre Abel-Remusat (1788–1832) and the Sinological Origins of Modern Buddhist Studies”; 雷慕沙(1788–1832)與現代佛教研究的漢學起源;

The name of Jean-Pierre Abel-Rémusat (1788–1832) is well known among Sinologists as that of the holder of the first academic chair of Chinese language and literature ever established in Europe and the West (Paris, Collège de France, 1815). His contribution to the early study of Buddhism in modern academia, however, seldom receives more than a passing mention, usually in connection to the posthumous publication of his translation of Faxian’s memoir (Foě Kouě Ki 佛國記 ou Relation des Royaumes Bouddhiques, 1836). Yet, Rémusat did so much more in this field: he used his erudite knowledge of Chinese sources to attempt for the first time a comprehensive understanding of the Buddhist religion, whose pan-Asian elephant he could clearly discern in a dark room where his predecessors had only seen an Indian trunk, a Burmese leg or a Japanese tail. Rémusat also mentored a promising young Sanskritist, and steered his fledgling scholarship from dry-as-dust philology to the systematic investigation of Buddhist texts. The Sanskritist was Eugène Burnouf (1801–1852), and this paper will argue that a not inconsiderable part of the credit he has taken as the father of modern Buddhist studies should in fact be returned to Rémusat, and to his extraordinary exercise of Sinology.

41. Jörg Plassen 虛說(University of Bochum 德國波鴻大學): “Some remarks on the notion of Sinification in the study of Buddhism, and some time-honored, yet persistent European schemata” 論佛學研究中的“中國化”觀念及一些歷史悠久且影響力尚存的歐洲模式;

The notion that the cataphatic approach of Huayan Buddhism should be seen as the result of a “sinification” or “sinicization” of Buddhism, i.e. its adaptation to Chinese modes of thinking, has proven rather resistent to criticism and is still widespread.

The idea as such seems to have found its way into Western secondary literature via the reception of Yūki Reimon’s 結城令聞 (1902-1992) musings on Du Shun’s Huayan, the process of “sinification” (chūgoku-ka) and the genesis of a “New Buddhism of the Sui and T’ang”, and on the backdrop of Paul Demiéville’s (1894-1979) model of a three stage “sinisation” of Buddhism in China.

The schemata underlying this perception, however, seem to be more time-honored: As to be argued in the paper, while the concept of sinification obviously can be traced to early 20th century German theology, the accompanying presuppositions concerning the nature of “the Chinese mind” have a much longer prehistory in European Sinology, theology and philosophy.

42. REN Pingshan 任平山 (Southwest Jiaotong University 西南交通大學): 克孜爾菱格畫中的蛇與龍 (Snakes and dragons in quilted drawings of Kizil)

佛教話語中的“那伽”,漢語意譯爲“龍”,在古印度和東南亞美術中常以眼鏡蛇形像指代,漢地佛教美術則更多表現爲中國式龍神。新疆克孜爾石窟中常繪“那伽”,如本生壁畫大施抒海、龍救商人;佛傳壁畫龍王守護、降伏火龍、龍王作橋、龍王問偈等等。克孜爾壁畫中的“那伽”總體更近蛇形,但龜茲畫家也試圖將之與真實蛇類予以區別,形像來源頗爲複雜。克孜爾壁畫中有兩類蛇形圖像主題不明:其一繪製群蛇各自盤繞;其二表現人類虐蛇之景。德國學者對其有過推測,國內學界未予采納。本文通過比對圖像和佛經文本,提出了自己的看法。

43. James Robson 羅柏松 (Harvard University 美國哈佛大學): “Iconophilia and Iconophobia: On the Attraction and Repulsion of Buddhist Images in the West” 符號崇拜與符號仇視: 論佛教圖像在西方的吸引與排斥力

In this paper I discuss why certain types of Buddhist images have been accepted, propagated, worshipped, and enshrined within Western museums (and museums of the imagination), while other types of images have been proscribed, actively destroyed, and ignored by scholars and museums. Certain sacred images and icons have presented problems for priests, politicians, philosophers, and academics who for various reasons have throughout history found them distasteful, attacked their validity and power, and have tried to hide them away or destroy them. Yet, even in the face of critique and destruction they have proliferated. In addition to discussing different types of images, I hope to also interrogate the bifurcation of museums into those with “high art” and those with “folk art” and link that split to issues of how some images are perceived to have a “transcendent” quality, while others are filled with the immanent presence of a deity. Why is it that the latter types of images have been so troubling and stirred up iconoclastic fervor?

44. Petra Rösch 石翠 (Museum for Asian Art, Cologne 德國科隆亞洲藝術博物館): “The influences of Schopenhauer’s ‘Buddhist’ concepts on Late 19th and early 20th Century German Collectors” 叔本華有關“佛教”的觀念對19世紀晚期至20世紀初期德國收藏家的影響;

Many aspects inspired Western collectors to buy Asian Art. Some might have been geopolitical, inspired by the riches of the colonies, or aesthetical, influenced by the resemblance of Tang Buddhist art to Greek sculptures, but for those, who became famous for collecting Buddhist art and especially sculpture, the religious or philosophical aspect of Buddhism seems to have been important. These collectors not only wanted to understand and represent the Buddhist pantheon as Emile Guimet wanted, but were at the same time drawn to Buddhism and finally also its aesthetic appreciation through the philosophical thoughts which inspired them.

In the following paper I will look at collectors like Eduard von der Heydt and question his sources of inspiration. I do claim, that the concept of Buddhism he and other collectors during the late 19th c. and early 20th c. had, was mediated by the philosophy and Buddhist understandings of Arthur Schopenhauer. I would claim that without this pre-mediation of Schopenhauer, Buddhist thoughts would not have been so readily welcomed at that time in Europe and thus might have changed the way of collecting world art.

Schopenhauer saw himself and his thinking so close to Buddhist philosophy, that he claimed to be a “Buddhaist” himself. Especially from his central works “Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung” and “Parerga and Paralipomena” these concepts can be extracted.

In my paper I want to question, how Schopenhauer understood Buddhism, which were the texts and thoughts he endorsed and which aspects provide the closest similarities or differences between his own and the Buddhist philosophies.

Which of Schopenhauers writings then, as well as which arguments did inspire the Western collectors, like Eduard von der Heydt and how did these influences change their conceptions of art.

45. Neil Schmil 史瀚文 (University of Vienna 奧地利維也納大學): “Empowering the Dharma: Automation and Techné in Medieval Chinese Buddhism” 加持佛法: 中古佛教中的自動操作與技藝;

During the medieval period, the importation from South and Central Asia of new Buddhist practices and beliefs into China inspired innovative methods and technologies for their enactment. A striking development in this process was the automation of cultic practices in the form of mechanical figures expressing forms of devotion and veneration. As early as the Jin Dynasty (265-420) processions featured carts with mechanized statues actively worshipping the Buddha or moving in circumambulation around the parinirvāṇa Buddha. Such examples made use of indigenous Chinese technology and mechanical engineering, but later developments, notably with esoteric Buddhism, necessitated the adaptation of imported ritual techniques and paraphernalia for new forms of knowledge and associated goals.

Dunhuang murals present discrete, detailed sets of such technologies and methods, most notably in murals of the Uṣṇīṣavijayadhāraṇī sūtra. This scripture, a 7th century import, marked a dramatic shift in prescriptive practices and the means to enact them. The formulation of these Dunhuang murals and their contents at once foreground the esoteric and palpably exotic practices of the scripture through new technologies, namely, ritual paraphernalia and innovative methods of textual presentation, while demonstrating how a seemingly agentless enactment of the scripture engenders automated distribution of the scripture’s efficacy. This talk analyzes these state-of-the-art religious technologies together with their origins in Central and Western Asia. A discussion follows on how automation, agency, and techné depicted in these Buddhist murals stand in a continuum through a similar logic of practice with other forms of automating the Dharma such as revolving sutra libraries and prayer wheels.

46. Koichi Shinohara 篠原亨一 (Yale University 美國耶魯大學): “Images and Mandalas in Esoteric Buddhist Ritual”; 密教儀式中的圖像與曼陀羅

Images, sculpted or painted, played a central role in the evolution of Esoteric Buddhist rituals, until their function became somewhat redundant with the extensive introduction of mental visualization. The confirmation of the ritual’s efficacy through image miracles was then replaced by mental identfication of the practitioner with the visualized deity. Maṇḍalas occupied a place similar to images in Esoteric Buddhis art. In this paper I propose to examine how they were also transformed by visualization. I will focus on the image / maṇḍala painting of the deity Buddhoṣṇīṣa vijaya and examine the ritual manuals attributed to Amoghavajra and Śubhākarasiṃha.

47. Kirill Solonin 索羅寧 (中國人民大學): Tangut Buddhist Art and the Buddhist texts 西夏佛教藝術與佛教文獻;

印度藏傳密教中,所謂“成就者”(mahāsiddha)的信仰占主要地位。據載,印度和西藏“成就者系統”有二種,其中第一是“84成就者系統”為Abhayadatta Śri所記載,另一個是“85成就者”系統,由金剛座(Vajrāsana,既是西夏人Rtsami lotsāwa Sangs rgyas grags pa )所記錄。二者存在著師弟關系。“85成就系統”在西夏比較流行,《大乘要道密集》中收錄《八十五成就祈禱文》就是屬於此系統,並與藏文原典相當接近。盡管如此,今有些新資料,其中是答應圖書館藏的一個殘片,曾屬於一種全文失傳的“成就頌”,另外有來歷不明的,私人藏的“成就頌”(高杉杉發現)。二篇資料內容有些交叉,足以有些初步討論。據其內容以及人名語音構擬二面觀之,二者屬於不同系統,並與85和84系統皆不相應。從此可知, 西夏流行的“成就者”系統並不限於85和84二者。

此外,黑水城出土的一部分唐卡上以及敦煌182窟中皆保留“成就者”圖像。問題是,這些圖像屬於哪一種成就者體系中。這涉及到另一個問題,即西夏佛教藝術與文本的關系。目前所見的研究成果大致上西夏佛像與西夏天體信仰的關系,另有喜金剛、上樂論、金剛亥母的次第和供養本子,但與西夏佛像的關系尚未得到學術界的足夠注意。這個報告還要談論另一問題,即西夏成就系統的文獻與其藝術品的關系到底應該如何處理。

48. Sun Yiping 孫亦平 (Nanjing University 南京大學): “Remarks on the Buddhist studies by Norwegian Missionary Karl Ludvig Reichelt [1877-1952]” 挪威傳教士艾香德牧師的佛教研究述評

民國時期,挪威傳教士艾香德牧師(Karl Ludvig Reichelt,1877~1952) 受挪威外邦傳教會的派遣帶著家人來到中國。當時中國正處於近代以來佛教文化的復興時期,其顯著的特點就是居士成為弘揚佛教文化的重要力量。一些來華的基督教傳教士也受居士佛教的影響,逐漸意識到“不研究佛學,不足以傳道”,其中就包括艾香德。

艾香德認識到,只有瞭解佛教,尤其是居士佛教,才能更好地傳播基督教,因此他努力學習漢語,通過閱讀漢文經典,研究中國宗教,尤其是大乘佛教。他還發起“宗教聯合運動”,推動宗教之間的理解和對話。他利用回國的時間,不僅積極在瑞典、丹麥、挪威發表演說,向人們宣揚他的宗教聯合的工作意義與具體計畫,而且還用挪威文著有一本研究中國佛教的書籍,Truth and Tradition in Chinese Buddhism,原版書於1922年於在瑞典出版, 1927年中國商務印書館出版了該書的英文本,書名改為《支那佛教教理與源流》。商務印書館在中國出版這本書,選擇的是英文而不是中文,後來多次再版,反映了二十世紀初西方人迫切地希望瞭解中國和中國佛教的要求。

受居士佛教及支那內學院的影響,艾香德在南京和平門外創辦景風山基督教叢林,後又把工作由內地遷移至香港,他積極宣導宗教對話與宗教聯合,依照佛教寺院制度,創辦了“道風山基督教叢林”,建築為中國式風格,其標誌就是十字架放置於佛教所崇奉的蓮花之上,表達了宗教對話以及基督教向佛教徒傳教的一種象徵。

艾香德通過研究佛教、瞭解佛教而進行的佛教化的傳教方式,一向爭議頗多,但不可否論的是他推動了歐洲對東方宗教文化的瞭解,以及推動了佛教和基督教之間的交流。他宣導的宗教對話至今仍有積極意義。

49. Sun Yinggang 孫英剛 (Fudan University 復旦大學): Images, Symbols and Politics: The Reception of the Cakravartin (Wheel-Turning King) Ideal in Medieval China 佛教轉輪王的圖像、符號及其政治意涵;

Speaking of Buddhism, from the very beginning China was not an isolated civilization. There was no a “Chinese Buddhism” in medieval world. Such a term has been invented and constructed by modern scholarship. For different “countries” of medieval Asia there was only one Buddhism. As I will discuss in this paper, the Buddhist Cakravartin ideal as a political ideology was shared by various regimes in South Asia, Central Asia, China, Korea, and even today’s Indonesia in Southeastern Asia. Buddhism in medieval period was not only a religion, but also a political ideology. China even used it as a united ideology for the unification of north and south China during the late 6th and early 7th century. The rise of spread of Buddhism in Asia was one of the most significant historical events before the 10th century. Its view of secular rulership was probably the only ideology accepted by most monarchs in today’s Asia. “Chinese Buddhism” cannot be well studied by separating it from the rest of world or Asia. It was part of the “globalization” of Buddhism in Asia. Many different civilizations and traditions were involved in the development of Buddhism from a local practice to a so-called “world religion” including Persian religions and even Greek culture. It has been conventionally accepted that Chinese Buddhism was introduced from India. However, it is only one aspect of the story. In the case of Cakravartin, we find that the Queli futu 雀離浮圖 or Cakra Stupa, which symbolized the authority of a Cakravartin, was first built by Kanishka I (r. 127-151 A.D.) of Kushan Empire. Then, Empress Wu’s adoption of Buddhist Cakravartin ideal as one of her main ideologies was part of the “globalization” which took Buddhism as a mechanism. Another historical context we should take into consideration is that even before her it had become a common practice for Chinese monarchs identified or were identified as Cakravartin. She was only one of these monarchs. 佛教在亞洲大陸的興起與傳播,不惟是宗教信仰的傳入與傳出,也是政治意識形態的衝突與融合。佛教對世俗君權有自己的一套觀念和看法,其傳入中國之後,在中土“天子”觀念之外,為世俗統治者提供了將自己統治神聖性和合法化的新理論,在中古時代的政治史上留下了深刻的痕跡。與中土植根於天人感應、陰陽五行思想、強調統治者須“順乎天而應乎人”的君主觀念相比,佛教對未來美好世界的描述,以及對理想的世俗君主的界定,都有其自身的信仰和思想背景。儘管佛教王權(Buddhist Monarchy)的傳統並沒有在中國歷史上形成長期的、佔據主導地位的影響,但是大乘佛教有關救世主彌勒(Maitreya)和理想君主轉輪王(Cakravartin)的觀念,從魏晉南北朝到唐代數百年間,曾對當時中土政治的理論和實踐都產生了重要的影響。這些影響包括政治術語、帝國儀式、君主頭銜、禮儀革新、建築空間等各個方面。隨著研究的深入,我們對中古時代作為政治意識形態的佛教有了進一步的認識。但是這些研究大多停留在文獻的梳理和分析上,對於圖像資料使用較少,而藝術史的研究者又鮮能揭示這些圖像、符號與中古政治的關聯性,在一定程度上影響了我們對整個歷史圖景的理解。筆者基於上述的考慮,希望圍繞作為佛教轉輪王身份標誌和權力象徵的“七寶”(saptaratna)展開討論,以相關圖像、符號為中心,討論相關觀念是如何影響中古政治世界的。除此之外,筆者也希望將中古中國受到佛教轉輪王觀念影響的情況,置於一個更為宏大的歷史語境和敘事之中,進而理解佛教對中國及其周邊政治傳統和文明的意義。所以,本文似乎講的是武則天的七寶,實際上揭示的是佛教的政治意識形態,而這種佛教的政治意識形態,也曾經被亞洲許多文明體都共同接受並付諸實踐,可稱之為“共用的意識形態”(shared ideology)。從這個角度講,武則天利用佛教宣揚自己的統治合法性並不特出,不但在中國中古的歷史脈絡中不特出,而且也僅僅是當時佛教世界普遍使用轉輪王來解釋王權這一潮流中的一環。

50. Teng Weijen 鄧偉仁 (Dharma Drum Institute of Liberal Arts 法鼓文理學院): “Western Evolution of Buddhist Studies and its Re-Contextualization in the East”; 佛教研究在西方的展開及其在東方的再語境化

Buddhist Studies as an academic field of study was evolved in the West during the 19th century, since then, it helped to create Buddhist Studies in the East in which the religion largely weaves into the fabric of the belief system of the people. It is therefore worth our while examining how the method and theory of Buddhist Studies developed in the Western context has been received in the context of East. Accordingly, this paper will explore some of the methodological and theoretical probrametics of Buddhist Studies when those “western” methods and theories were introduced, studied, and applied by, particularly, the East Buddhist students of the “Buddhist Colleges” in Taiwan.

51. Barend ter Haar 田海 (University of Oxford 英國牛津大學): “Buddhism, shamans, mediums and witches”; 佛教、薩滿、靈媒與女巫

My preliminary paper will deal with the interactions between Buddhist religious or ritual specialists and the surrounding religious world, and figures whom we would today describe as shamans or mediums in particular. At this stage of the project, I will focus especially on early evidence until the late Tang. We will look at this relationship both in terms of direct interaction, but also of implicit competition between old style religious specialists who once dominated local communities and the increasing importance of these Buddhist upstarts. Although it may seem obvious that the separation between these different categories would be quite systematic, there also anecdotes which indicate that there was some form of accommodation.

52. Stefania Travagnin 史芬妮 (University of Groningen 荷蘭格羅根大學): “The Contribution of European Buddhist Studies to East Asian Buddhist Studies: The case of Étienne Lamotte and the research on Da zhidu lun” 歐洲佛學對東亞佛學的貢獻: 以拉莫特與《大智度論》的研究為例;

Étienne Lamotte (1903-1983) was a Belgian priest and at the same time an eminent scholar of Buddhist history and scriptures. One of his most well-known accomplishment, which had been unfortunately left unfinished, has been the French translation of Da zhidu lun 大智度論 (T25 No.1509). Da zhidu lun is a very popular text in East Asia, also because it is attributed to Nāgārjuna, the so-called “patriarch of the eight schools” (ba zong zhi zu 八宗之祖) in East Asian Buddhism. Belgian Lamotte, however, claimed that Nāgārjuna might have not written Da zhidu lun.

Lamotte’s theory received attention, and consensus, of other Western Buddhist scholars like Conze, and also influenced contemporary Japanese Buddhologists, who then came to represent Lamotte’s legacy in the Far East. Lamotte’s claim led to various debates that eventually gave rise to a wide array of hypotheses and claims of who the author of Da zhidu lun could have been. The theory that Da zhidu lun could have been a text not (or not only) written by the very authoritative Nāgārjuna created several debates among Chinese Buddhist monks and scholars as well, and thus the sparking of further response to Lamotte and the Japanese.

This paper will show the impact of Western scholarship on East Asian Buddhism, highlight the (pluri)directionality of knowledge transfer, and demonstrate relevance and potentiality of the dialogue between East and West for the advancement of Buddhist learning.

53. Wang Bangwei 王邦維 (Peking University 北京大學): “European Buddhist Scholarship in Chines Eyes” 歐洲的佛教學術研究: 中國人怎么看?

佛教的學術研究在歐洲(包括後來的美國)是近代才有的事。一般來說,歐美的學者都是以“他者”的身份來審視和研究佛教。佛教在亞洲,尤其是在東亞和東南亞,則一直是活著的宗教。中國曾經是其中最活躍的一個地區。歷史上中國人對佛教的研究,既有信仰的原因,但也部分地包含了學術的成分。近代以來,中國社會發生了巨大的變化,學術研究向現代轉型,中國的學者,他們中一部分有佛教的信仰,一部分則沒有,他們怎麼看待和理解歐洲學者的佛教學術研究,是至今還在討論的題目。今後數十年裡,中國學者與中國以外的佛教研究的學術共同體怎樣互動,不僅會影響到中國自身的學術發展,顯然也會對國際上佛教學術研究整體的態勢產生越來越大的影響。

54. Eugene Wang 汪悅進 (Harvard University 美國哈佛大學): “Why Was There No Pantocrator’s Stare on Buddhist Chapel Ceilings?” 佛教石窟穹顶为何不设全知天眼?

One striking feature of the Buddhist cave design emerges from a comparison with Byzantine chapels. While both the Mediterranean Christian and Asian Buddhist chapels have similar dome designs, the difference between the two ceiling-decoration traditions is just as striking. The stare of the Pantocrator, or All-Mighty, commonly seen on Byzantine chapel domes is conspicuously absent in Asian Buddhist cave chapel ceilings. What accounts for the difference? Given that presence of the Mediterranean-style dome design in Buddhist caves, it would have been easily conceivable that the central disc, conventionally reserved for the Christian Pantocrator with his all-knowing stare, could have easily been adapted to feature a Buddha, equally in half-bust, looking down at the beholder. That step, however, was never taken. The fact naturally raises the question of why. One additional fact makes this absence of the Pantocrator’s stare in Buddhist cave chapel ceilings all the more intriguing. While the Pantocrator’s omniscient stare is conspicuously absent on Buddhist chapel ceiling, the idea of the all-seeing eye—the “Heavenly Eye”—is very much alive and present behind the design of the pictorial program of Buddhist cave chapels. Moreover, the concept of the all-seeing eye, hitherto unknown to East Asia, was apparently fast gaining traction there with the spread of Buddhism. How do we then account for this discrepancy? What is it about the concept of the Buddhist “Heavenly Eye” that never takes the visual form of the stare of the Christian Pantocrakor?

55. Wei Bin 魏斌 (Wuhan Univesity 武漢大學): 山寺與墓所——南朝鐘山的佛教景觀與空間格局Mountain Temples and Graves: The Buddhist Landscape and the Arrangements of Space at Mount Zhong in the Southern dynasty;

南朝以前鐘山的宗教景觀,主要是位于西北麓的蔣子文廟,東晋帝陵有的也分布在這一區域。劉宋以後,佛教寺院逐漸在鐘山蔓延,最集中的區域則是在南麓(今明孝陵一帶),鐘山成爲南朝最重要的佛教山林之一。與之相關的一個重要事件,是南齊時期蕭子良“疆界鐘山”,在此設立名僧墓所,幷一直沿用到南朝末期。山寺和名僧墓所建立和擴展的背後,是鐘山與建康王權的密切關係,是城內政治權力向城外的“溢出”過程。以鐘山南麓爲核心的建康郊區佛教空間的形成,從某種意義上理解,也可以看作一種外來文化影響下的景觀變動過程,是中國都城發展史上的一個新現像。

56. Verena Widorn (University of Vienna 奧地利維也納大學): “The Impact of Buddhist Cave Paintings on the Modern Art of Europe and Asia”; 佛教洞窟繪畫對現代歐亞藝術的影響

57. Jiang Wu 吳疆 (University of Arizona 美國亞利桑那大學): “Finding the First Chinese Tripitaka in Europe: The 1872 Iwakura Mission in Britain and the Mystery of Ōbaku Canon in the India Office Library”; 尋找歐洲的第一部漢文大藏經: 1872年在英國的岩倉使團與印度事務部圖書館《黃檗藏》的奧秘

Although the creation of the Chinese Buddhist canon is a well-known event in East Asian cultural sphere, little is known about when and how Westerners became interested in this great textual tradition. As far as I know, the first Chinese Buddhist canon in Europe was a version of Northern Ming Canon which was reprinted in the main section of the Jiaxing canon and later in the Obaku canon in 1673 in Japan because of the promotion of the Jiaxing canon by the Chinese monk Yinyuan Longqi (1592-1673), the founder of the Japanese Obaku Zen tradition. In the late nineteenth century, Max Müller (1823-1900), the early pioneer in comparative religion, started a massive translation project of “Sacred Books of the East.” For this project, a request for Buddhist books was sent to Japan and the Japanese ambassador Iwakura Tomomi (1825-1883), the court noble who initiated the Meiji Restoration, responded with a delivery of an entire set of the Obaku edition to the Indian Office Library in London. (This set of the canon is still housed in London) Sinologist Samuel Beal (1825-1889) and Max Müller’s Japanese student Nanjō Bunyū (1849-1927) translated its entire catalogue into English in 1876 and 1883 respectively. In an attempt to rediscover the first Chinese canon in the West, my paper will investigate various historical events leading to the arrival of this canon in Europe and how Western interests in Eastern religions brought the canon to Britain through diplomatic maneuvers.

58. Yao Chongxin 姚崇新 (Sun Yat-sen University 中山大學): 十字蓮花: 佛教藝術對基督教造型藝術在東方的影響; (The cross-shaped lotus: the impact of Buddhist arts on Christian arts in the East)

自公元7世紀前期景教入華始,基督教造型藝術開始在中國出現,其後一直與基督教在華的傳播相始終。梳理唐、元及明清時期的典型的基督教藝術遺存不難發現,其受佛教藝術的影響非常明顯,而基督教藝術對佛教藝術的影響甚微。本文結合早期入華基督教對佛教思想的主動吸收以及佛教對早期入華基督教的態度等歷史情狀,對上述現像試作分析,幷試從基督教理的角度分析入華基督教在造型藝術方面吸收佛教藝術元素的可能性。

59. Stuart Young 楊啓聖(U. of Bucknell 美國巴科內爾大學): “Shaping Monastic Identity in the Silk Cultures of Medieval China” 在中古中國絲綢文化中塑造僧侶身份;

Sericulture has always been a central defining feature of Chinese civilization, and silk a cornerstone of Chinese Buddhist material culture. In many ways silk was the fabric of monasticism throughout premodern China, infused within the material and ideal worlds of Chinese Buddhists. Against the backdrop of normative Indian Buddhist pronouncements concerning material production, commercial engagement, attachment to luxury goods, and especially killing living beings, the topic of Chinese Buddhist silk culture offers novel insights into monastic identity as a negotiation between avowedly foreign religious paradigms and widespread, culturally embedded, traditions of material production.

This article examines a tale told in Indian vinaya texts about Buddhist monks who killed silkworms for their silk. This tale appears to instantiate a disjuncture between Buddhist ethics and jurisprudence, as it condemns the act of killing not on soteriological but on social grounds: i.e., confusing monastic distinctions. Medieval Chinese vinaya commentators attempted to reconcile this disjuncture, insisting that the vinaya precept in question incorporate Mahāyāna teachings of universal compassion toward all living beings – including silkworms especially. In this way, Chinese Buddhists defined for themselves – on the grounds of Indian precedents – a new kind of monastic identity that diverged from Indian norms. Here lay-monastic boundaries were drawn in terms of the propriety of silk – from ethical, soteriological, social, and juridical perspectives – which was one important material cultural arena in which Buddhist identity was negotiated in premodern China.

60. Yu Xin 余欣 (Fudan University 復旦大學): “Glass in Buddhist Ritual and Art in Medieval China” 中古中國佛教儀式與藝術中的玻璃

In Buddhist texts, glass (in Chinese, poli 頗梨 or 颇黎, liuli 琉璃, 瑠璃 or 流离, boli 玻璃 or 玻瓈, transliterations of sphaṭikā from Sanskrit) was considered as one of the Seven Treasures (qibao 七寶). The author investigated all kinds of materials concerning glass: Buddhist scriptures, historical records, Chinese poetries and literatures, stone inscriptions, manuscripts and paintings from the Dunhuang Library Cave, mural paintings in Gansu and Xinjiang, cultural relics from terrestrial palaces of Buddhist pagodas, tombs, cellars, and archeological sites along the Silk Road, and focuses on the relationship between glassware and other unearthed remains in a holistic approach to the Seven Treasures, and in the context of Buddhist offerings (treasure offering and perfume offering) and sacred utensils.

The author hopes to cast some new light on the religious function and symbolic meaning of glass in Buddhist ritual practices, trace the origin of this concept and examine its demonstration in text and art. This paper is a case study intended to develop a comprehensive understanding of ritual texts and religious practices in the using of sacred artifacts and to rethink the role of material culture in Buddhist history and Bowuxue 博物學 in Medieval China.

61. Dewei ZHANG 張德偉 (Sun Yat-sen University 中山大學): “For the Deceased? For the Living?: Revisiting jiao Buddhism in Late Imperial China, with a Special Reference to Funeral Music” 爲逝者抑或爲生人?:再議帝制晚期中國佛教的“教”,特別以葬禮音樂爲參考

Esoteric Buddhist practices (jiao 教), which promoted the offering of liturgical services for the dead, appeared as an independent category of Buddhism in the early Ming dynasty and quickly gained extraordinary importance within the saṃgha. By the late nineteenth century, it is estimated that at least sixty percent of the monk population had become liturgical specialists. But this dominance of jiao Buddhism within the saṃgha attracted violent attack from critics like modern reformers Master Taixu 太虛 (1890- 1947) who depreciated Chinese Buddhism of the period as the “religion of the dead.” Of particular interest here is the extensive use of music in funerals. Some leading figures found the practice vulgar, criticizing that it was an evil distraction of the genuine practice of Buddhism and thus a sign of decline. Things can be very different if we consider them from a new angle, however. The music present in this situation was frequently localized and kept updated. It helped to satisfy the need of the living for entertainment, a desire that the majority of people, especially those living in the countryside, found increasingly hard to satisfy in late imperial China. In this way, music actually served as a catalyst that helped Buddhism to exert and maintain influence in Chinese society. Similar strategy can be seen even in earlier times, such as the populace of the bianwen 變文 (transformation texts) in medieval China. Morally disgusting though it was, the extensive use of music in funerals did not cause the decline of Buddhism as some people believed. Rather, it was aimed to serve the living rather than the dead, which makes the critique by Master Taixu partly untenable, and contributed to the survival and growth of Buddhism at the time. 以爲逝者提供喪禮服務爲主要工作的“教”,自明初成爲佛教一個獨立類別後,迅速在僧團取得了非同尋常的重要性。到19世紀晚期,估計至少60%中國僧人的活動都以做喪事爲主。“教”在佛教中的這種主導性地位招致了激烈攻擊,批評者包括近代指責中國佛教已經淪爲“死人宗教”的太虛大師。喪禮中音樂的大量運用尤其成爲攻擊目標。一些領袖人物認爲這很粗俗,批評它干擾了人們從事真正的佛教實踐活動,是佛教墮落的象徵。但是如果我們換種角度考慮,此事就呈現了非常不同的性質和樣態。在喪葬場合出現的音樂,經常都會地方化幷且隨時更新。它幫助滿足了活人的娛樂需求--滿足這種需求,對生活在帝制晚期的中國人尤其是農村的中國人來說,日益困難。所以 ,這些音樂在事實上扮演了一種催化劑角色,幫助佛教在其時的中國社會發揮和保持其影響力。與此類似的策略,早前佛教史中即可發現,例如在中世紀中國盛行的變文。在喪禮中大量使用音樂,雖然在道德上或許讓人難于接受,但它幷未某些人所相信的那樣導致了佛教的衰落。相反,它以死人的名義服務於活人,幫助維持了佛教的生存和發展,也動搖了太虛等人指責“教”的基礎。

62. Zhang Xiaogang 張小剛 (Research Institute of Dunhuang 敦煌研究院): 于闐白衣佛瑞像研究——從敦煌壁畫中的于闐白衣立佛瑞像圖談起 (A Study on White-clad Buddhist Icons in Khotan: Centering on the Khotan White-clad Buddhist Icon of a Standing Buddha in Dunhuang Murals);

在敦煌瑞像圖中,有一些身著白色袈裟的于闐立佛瑞像,如“從憍賞彌國騰空來住于闐東媲摩城佛像”“從漢國騰空而來在于闐坎城住釋迦牟尼佛白檀香身真容”“于闐海眼寺釋迦聖容像”“從王舍城騰空而來在于闐海眼寺住釋迦牟尼佛白檀身真容”“迦葉佛從舍衛國騰空于固城住瑞像”“微波施佛從舍衛城騰空來在于闐住瑞像”“結迦宋佛從舍衛國來在固城住瑞像”“伽你迦牟尼佛從舍衛國來在固城住瑞像”等題材,這些造像多數在背光中布滿化佛或者頭上戴冠系帶。

斯坦因(A. Stein)在中國新疆和田地區法哈特伯克亞伊拉克(Farhad Beg Yailaki)遺址發現了白衣立佛的兩塊木板畫,在熱瓦克佛塔寺院則發現了兩尊在背光中布滿化佛的大立佛。本世紀初在達瑪溝托普魯克墩1號佛寺遺址又發現了在背光中布滿化佛的白衣大立佛,是敦煌繪畫中相關造像的原型。新疆克孜爾等石窟中也發現了在背光中布滿化佛的立佛像,這種造像樣式,可能與舍衛城神變故事對佛教造像的影響有密切關係,在犍陀羅藝術中也有這種造像形式的原型。在印度阿旃陀石窟第10窟石柱表面壁畫上,也有笈多王朝時期用白描墨綫繪製的白衣佛。由此我們瞭解白衣佛造像從印度到西域,再到敦煌的傳播情况。

63. ZHANG Yong 張勇 (Sichuan University 四川大學): 轉輪藏與轉書輪:西方傳教士輸入物與東亞佛寺設置之比較研究 (The Wheel Turner of Buddhist Canons and the Catholic Turning bookshelves: A Comparison of inputs by Western missionaries and Structures in Eastern Asian temples);

神聖羅馬帝國 (Heiliges Römisches Reich deutscher Nation/Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation) 時期(962-1806)的天主教耶穌教會傳教士Johann Schreck(1576~1630。中文名:鄧玉函),曾于明朝末期來華傳教。由其口授、教徒王征譯繪的《遠西奇器圖說錄最》于天啓七年丁卯(1627)刊行,書中圖文幷茂地介紹了一種“轉書輪”,即旋轉書架。“轉書輪”後亦爲朝鮮李朝實學派“四大家”詩人李德懋之孫、實學派思想家李圭景所知曉,其撰《五洲衍文長箋散稿》稱之曰“轉架”。揆諸中國寺院的類似設施,則爲梁陳之際的“雙林樹下當來解脫善慧大士”傅翕(497~569)所始創的轉輪藏;然轉輪藏早在上千年前已然在江浙地區出現,唐代普及全國佛寺,宋元更傳入朝鮮半島和日本列島。本文擬對二者的源頭、結構、功用和影響等,略作考證和比較,期以揭示出佛教徒和傳教士心目中理想的圖書陳列、貯藏和閱讀工具雲爾。

64. Zhang Yuanlin 張元林 (Research Institute of Dunhuang 敦煌研究院): 跨越洲際的旅程:關于敦煌壁畫中日神、月神和風神圖像上的希臘藝術元素 (A trans-continent trip: Greek elements in images of the gods of the sun, the moon, and the Wind found in Dunhuang murals);

經過西元4世紀——14世紀間持續千年的營建,敦煌石窟為我們保留下了大量的反映古代歐、亞大陸不同文明、文化之間相互交流、影響乃至於融合的歷史的圖像資料,敦煌藝術因而也呈現出鮮明的“多元性”特徵。其中,敦煌壁畫中那些隱約閃現著古代希臘藝術之光的圖像元素,為我們暗示著歐洲古典文明對亞洲古代文明的發展所做出的貢獻。敦煌壁畫中的希臘文化元素,從建築、裝飾圖像和神祇形象等圖像上皆有反映。本文即以敦煌壁畫中的“乘馬車”日神、“乘鵝車”月神和“執風巾”風神這三類為例,通過與其它地區發現的同類圖像的比較,探究其可能的傳播軌跡,從一個側面展示古希臘藝術跨越時空,對東方古代藝術、特別是佛教藝術所產生的深刻而持久的影響。

第一,關於敦煌壁畫中的“乘馬車”日神、“乘鵝車”月神圖像及其來源

敦煌石窟中有超過100個洞窟中繪有日神和月神圖像的,這些日、月神圖像多以組合形式出現,大體上可分成三種類型。其中的“乘馬車”日神、“乘鵝車”月神圖像組合數量最少。它又可分為“馬、鵝呈兩兩相背姿”和“中間一身馬、鵝呈正向面姿、兩側呈兩兩相背姿” 兩種子類型。前者在敦煌僅出現一例,出現在約完工於西元539年左右的莫高窟第285窟。值得注意的是,在日神和月神車的下部,又分別繪有一輛由三隻鳳鳥和三隻獅子牽拉的車駕,上有手持盾牌的武士,似在護衛日、月神;後者數量多達20多例,最早見於8世紀中晚期的密教題材繪畫中,一直持續到了13世紀,且在敦煌藏經洞發現的絹畫中也有數例。

首先,與“乘馬車”日神相同或相似的圖像,除了熟知的印度教太陽神蘇利耶神雕刻外,在中國新疆庫車石窟、中國青海省都蘭縣的吐蕃人墓葬、阿富汗巴米揚石窟、巴基斯坦犍陀羅地區、今天塔吉克斯坦片其肯特地區的粟特人遺址的出土物以及製作於西元1世紀初的古羅馬帝國的一位皇帝的大理雕像上皆有發現。但是,更早的乘馬車的太陽神圖像則大量見於希臘本土和世界各地博物館所藏的希臘彩陶圖案、以及希臘德爾菲的阿波羅神廟遺址。筆者認為,敦煌壁畫中的“乘馬車”日神、“乘鵝車”月神圖像、特別是第一種子類型圖像,其最早的原型可追溯至古希臘—羅馬文化中的太陽神形象。這種圖像,很可能隨著亞歷山大的東征及其後的“希臘化”過程中傳播至西亞波斯和巴克特利亞地區,並成為袄教的太陽神密特拉圖像的構成部分,其後又在犍陀羅地區發展成為具有多元文化印記的佛教的日神或月神的圖像之一並經中國的新疆地區傳入敦煌。在這裡,又加上了中國文化的元素。這一漸進的傳播過程前後延續達七、八百年之久。

其次,令人感到奇怪的是,我們至今未在印度本土發現一件“乘鵝車”的月神圖像。但是,在印度以外的愛琴海地區卻發現了米諾斯時期(西元前3000-前1450年)的“大地之母”雙手各執一鵝頸的雕刻;而古希臘城邦守護神的希波利(Cybele)女神與其坐騎獅子的雕刻作品,亦發現多例。甚至在今阿富汗阿依·哈努姆的“希臘化”古城遺址中也發現了製作於西元2世紀左右的乘獅車的希波利女神雕刻。而且,從考古發現和文獻記載來看,早在古代兩河流域文明、古埃及文明、古希臘等地中海古代文明中,女神信仰和月神信仰就十分為興盛。相反,雖然印度教中的日神蘇利耶的雕刻十分盛行,但似乎並沒有發現與有之相匹配的月神雕刻。綜合以上這些因素來看,敦煌壁畫中作為“乘馬車”日神的對應神祇,“乘鵝車”月神圖像的原型很可能也在中亞、西亞、兩河流域甚至更遠的地中海周邊地區。

第二、關於敦煌壁畫中的“執風巾”風神圖像及其來源

敦煌壁畫中的風神圖像,可分為“口中吹風”型、“手執風囊”型和“執風巾”型這三種。其中,“執風巾”風神圖像,在敦煌壁畫中僅見兩側。一例見於營建於西元5世紀末—6世紀初的莫高窟第249窟頂,另一例見於前述莫高窟第285窟西壁所繪的摩醯首羅天的頭冠中。“執風巾”風神圖像在敦煌以東地區,目前只見到一例,但在敦煌以西地區,在中國新疆庫車克孜爾石窟、阿富汗巴米揚石窟、古代貴霜王國時期錢幣的背面均可見雙手執風巾的、作奔跑狀的風神形象。而且,這些風神形象本身,具有明顯的希臘人的冠飾。更有甚者,在阿富汗始建於西元前2世紀的貝格拉姆古城遺址也發現了帶有明顯希臘文化印記的彩繪玻璃杯上化作風暴神的手執風巾的宙斯(Zeus)圖像。筆者認為,“執風巾”的風神圖像,其圖像淵自希臘。而且,從目前所見的此類圖像皆未早於西元前2世紀這一點來看,這種“執風巾”的風神圖像的出現在中亞地區,很可能亦是亞歷山大東征及其後歐亞腹地长期的“希臘化”的結果,其后並經中國新疆地區影響到了敦煌,並在圖像上發生了一些變化。

特別需要指出的是,從一些貴霜時期的錢幣背面圖案中由公牛相伴、手持三叉戟的神祗形象旁的古希臘文題銘可知,它們也是貴霜風神的另一種圖像。這一結論也從在古代兩河流域和美索不達米亞地區發現的數件製作於西元前2000年——西元前1000間的、同樣地手持三叉戟、站立于公牛背上的巴比倫風暴神形象上得到印證。它們也清楚地表明,早在古巴比倫文明中,三叉戟和公牛就已經成為風暴神的圖像元素的一部分了。而在前述阿富汗貝格拉姆古城遺址發現的彩繪玻璃杯上化作風暴神的宙斯(Zeus)圖像即集“執風巾”與“騎公牛”於一體。在500年之後的西元六世紀前半,在相距數千公里之外的敦煌,這兩種圖像特徵再一次“頑強地”結合在了第285窟的摩醯首羅圖像上,的确令人驚歎!反映出希臘文化、波斯文化、巴比倫文化漸進式的、間接的影響。

65. Zhang Zong 張 總 (Institute of World Religions Chinese Academy of Social Sciences 中國社會科學院世界宗教研究所): 佛教繪畫重要圖式——水月觀音像起源之探查 (An important model of Buddhist drawings: On the origins of the image of Water-moon Guanyin)

水月觀音像是佛教美術中最重要的圖式之一,畫史紀載“周家樣”即唐代大畫家周昉“妙創水月之體”。石窟藝術中發現早期壁畫及絹畫,論者以為可以圖史互證,闡述演證水月觀音像式之源流。但敦煌藏經洞寫本有五代的“水月光觀音經”,實際竟是《千手經/大悲呪》的啟請文。從日本入唐高僧所攜經像目錄等等,可知水月與千手觀音像確有關連。雖然仍有學者對此並不認同。此中情況究屬如何?筆者從顯密兩系經典圖像源流剖析,水月觀音圖式中之月,實應是觀音身後的圓光。而佛菩薩像式中圓月式的背光,實是具有月輪觀的密宗圖像之特點。顯宗像畫圖式中從未有過圓月式的背光。由此出發,可以解決千手密宗系觀音與水月觀音像圖式的關系之基礎聯結點水月觀音像是佛教美術中最重要的圖式之一,畫史紀載“周家樣”即唐代大畫家周昉“妙創水月之體”。石窟藝術中發現早期壁畫及絹畫,論者以為可以圖史互證,闡述演證水月觀音像式之源流。但敦煌藏經洞寫本有五代的“水月光觀音經”,實際竟是《千手經/大悲呪》的啟請文。從日本入唐高僧所攜經像目錄等等,可知水月與千手觀音像確有關連。雖然仍有學者對此並不認同。此中情況究屬如何?筆者從顯密兩系經典圖像源流剖析,水月觀音圖式中之月,實應是觀音身後的圓光。而佛菩薩像式中圓月式的背光,實是具有月輪觀的密宗圖像之特點。顯宗像畫圖式中從未有過圓月式的背光。由此出發,可以解決千手密宗系觀音與水月觀音像圖式的關系之基礎聯結點。