Mañjuśrī in Motion 常進不居之文殊:

Multi-cultural, Cross-religious Characteristics and International Impact of the Wutai Cult 五臺山信仰多文化、跨宗教的性格以及國際性影響力

Primary Sponsor 主辦方: The Wutai International Institute of Buddhism and East Asian Cultures (佛教和東亞文 化) 五臺山國際研究所

Secondary Sponsors 協辦方: King’s College at the University of London 倫敦大學國王學院 Tsinghua Institute for Ethics and Religions Studies (IERS) 清華大學道德與宗教研究院 Fudan Buddhist Studies Forum 復旦大學佛學論壇 UBC Buddhist Studies Forum 英屬哥倫比亞大學佛學論壇

Host 承辦方: Great Sage Monastery of Bamboo Grove 大聖竹林寺

Venue 地點: Great Sage Monastery of Bamboo Grove, Mount Wutai 五臺山大聖竹林寺

Dates 時間: Afternoon of July 19 (Opening Ceremony & Keynote Speech Session) 7月19日下午 (開幕 式及主題演講) ——July 20 (tour on Mount Wutai) 7月20日 (五臺山參訪) ——July 21- 22 (conference) 7月21至22日 (會議)——July 23-24 (tour in Datong, including the Yungang Grottoes complex and several major temples in Datong) 7月23至24日 (參訪 大同,包括雲岡石窟及幾大名寺)

Located in central China, the mountain range known as Wutai 五臺 was perceived as the new Chinese abode for the famous Indian bodhisattva, Mañjuśrī. As such, it came to be widely venerated by Buddhist believers from all over East Asia. This conference explores a plethora of trans-cultural, multi-ethnic, and cross-regional factors that contributed to the formation and transformation of the cult centered on Wutai and its dwelling bodhisattva (Mañjuśrī), as well as the “international” roles (religious, political, economic, commercial, diplomatic and even military) that the Wutai-centered cult has played in Asia and beyond. 地處中國的中部,這座名為五臺的山脈被認為是印度文殊師利菩薩在中國的新道場,因此,這座山脈也受到整個東亞地區佛教信仰者的廣泛崇奉。本次研討會探讨促發五臺山和文殊師利崇拜的形成和轉變的大量的跨文化、多種族、跨地域的因素,以及五臺山崇拜的在亞洲內外所扮演的多重國際性角色(包括宗教上、政治上、經濟上、商貿上、外交上、甚至軍事上的諸多方面)。

Topics for this conference include, but are not limited to 本次研討會所涉及的話題包括但不限於以下幾個方面:

- Wutai’s status as a pilgrimage center in Asia 五臺山作為亞洲的一個朝聖中心;

- Various patterns of interactions between different religious traditions at Wutai五臺山上不同宗教互動的模式;

- Presence of and interactions between different Buddhist traditions (Chan, Tiantai, Pure-land, Vinaya, Esotericism, Tibetan Buddhism, etc) at Wutai 不同佛教宗派 (禪宗、天台、淨土、律宗、密宗、藏傳佛教等)在五臺山上的存在和互動;

- Political and military uses of Wutai by competing powers in East Asia (the international rivalry revolving around Wutai, intensified by its location as a frontier territory for several major forces in Central and East Asia) 東亞地區不同的競爭勢力對五臺山的政治性和軍事性利用 (圍繞五臺山展開的國際性競爭,以及這種競爭如何因五臺山地處不同政權的交界處而日趨劇烈);

- Imagination and perceptions of Wutai in East Asian countries and regions beyond China 五臺山在東亞各國家的想像和認識;

- Wutai as the model on which sacred sites (including sacred mountains, temples, and shrines) were “cloned” in the rest of Asia (Korea, Japan, Vietnam, and Central Asia) 五臺山作為一種模型,為各個亞洲地區 (包括韓國、日本、越南、與中亞)的聖地(包括聖山、大寺、祠廟等)所效仿;

- Wutai as the source of inspiration for different forms of literature and arts in Asia五臺山作為一個啟發亞洲文學和藝術創作的源泉;

- Wutai as the source of revelations for religious traditions, both Buddhist and non-Buddhist 五臺山作為宗教傳統—佛教和非佛教的—的啟示源泉.

The organizing committee welcomes paper proposals related to any aspect(s) of the “internationality” and cross-culturalism of the cult centered on Wutai and/or Mañjuśrī. All conference-related costs, including, local transportation, meals and accommodation during the conference period, will be covered by the conference organizers, who—depending on availability of funding—may also provide a modest travel subsidy to selected panelists who are in need of funding. This conference is planned as a continuation of a conference on the Wutai cult that was held last summer at Mount Wutai: 組委會歡投寄論文提要,論文只需與上述五臺山或文殊崇拜的國際性和跨文化任一課題相關即可。與會的相關費用,包括會議期間的食宿費用,將由會議組織方承擔。會議組織方也將視資金的寬裕度,為部分有需要的與會成員提供部分旅費津貼。本次研討會是去年夏天在五臺山舉辦的一次會議的續期,詳情請參見:

Our goal is to bring 15-18 international scholars to the conference, who will be joined by an equal number of China-based scholars working on the Wutai cult. Similar to the last Wutai conference, the conference this coming year will generate two conference proceedings: one in English and the other in Chinese. The English volume will collect all the papers in English, plus the English translations of several papers written in non-English languages; the Chinese volume, to be published in China, will include the Chinese versions for all non-Chinese papers in addition to those papers contributed by our colleagues based in China. Only scholars who are confident in finishing their draft papers by the end of June and publishable papers by the end of 2016 are encouraged to apply. 我們目標是匯集15-18名國際學者,與同樣數量的中國學者一道探討五臺山崇拜。與上次會議一樣,今年的會議也會出版一英一中兩卷論文集。英文卷收錄用英文著述的論文,也包括數篇非英文論文的英譯;中文卷將在中國出版,除了中文論文,還將收入所有非中文論文的漢譯。6月底前有把握完成論文初稿,并在年底前完成够出版水平論文的學者,歡迎申請與會。

This conference is planned as part of our annual Intensive Program of Lectures Series, Conference/Forum, and Fieldwork on Buddhism and East Asian Cultures. Interested graduate student and post-doctoral fellows are welcomed to apply for the whole program: 本次研討會是我們每年的佛學與東亞文化集中營(包括系列講學、會議、論壇、田野調查)一個組成部分。歡迎有興趣的研究生和博士后申請本活動,詳情請參閱網頁:https://blogs.ubc.ca/dewei/2016-summer-program-buddhism-and-east-asian-cultures/

确定參會者名單:

1. T. H. Barrett 巴瑞特 (SOAS, The University of London 英國倫敦大學亞非學院): “Wutaishan and the Northern Wei: An Explanatory Hypothesis” 五臺與北魏:一個解釋性的假說

The area of Wutaishan was no doubt always considered special by the local inhabitants from very early times, though details about this are hard to find. The first foreign people that appear to have shown an interest in the place seem to have been the Northern Wei, as far as we can judge from Tang period sources. Yet their traces at Wutaishan are not very obvious, unlike the massive works at Yungang 雲崗. Why was this? By using scholarship published in English it is at least possible to come up with an explanatory hypothesis that answers this question. 從很早開始,對於當地人來說,五台山地區就已經不是等閒之地了,這是毫無疑問的,只是不可詳考。 根據唐代的資料 ,最先對這塊地方表示興趣的外族是北魏。然而,他們在五台山的遺跡並不十分赫然,這與他們在雲岡的大興工事形成對比。何以致此?藉助相關英文學術成果,我們也許可以提出一個假說以回應上述問題。

2. Ester Bianchi 黃曉星 (Università degli Studi di Perugia, Italy 義大利佩魯賈大學): “Bodhisattva Precepts in Modern China: The case of Nenghai 能海 (1886-1967) on Wutaishan” 現代中國的大乘戒: 五台山能海(1886-1967)之一例

Nenghai 能海 (1886-1967), a main representative of the Sino-Tibetan Buddhist tradition, was also a convinced advocate of monastic discipline. He not only focused on the so-called “hīnayāna vinaya” (xiaosheng jielü 小乘戒律), but he also aimed at reviving the Bodhisattva precepts (dasheng jielü 大乘戒律, *māhayāna vinaya). The study and practice of discipline was central throughout his monastic life, but it increased with the passing of time, as can be inferred by the choice to name his last monastery Jixiang lüyuan 吉祥律院 (Jixiang vinaya institute). Located on Mt Wutai, it soon became exemplary for its disciplinary rigour.

The main objective of this study is to investigate the role and nature of Bodhisattva precepts in Nenghai’s tradition. In spite of referring to the Bodhisattva precepts inspired by the *Brahmājalasūtra, which were followed by Chinese Buddhists and were conferred during ordinations in China, Nenghai and a few other prominent Buddhist masters of the time preferred the Yogācāra Bodhisattva precepts (yujie pusajie 瑜伽菩薩戒), as in the Tibetan and Japanese traditions. This was a new wave within Chinese Buddhism, revealing a trans-traditional and trans-national character and which, at least in the case of Nenghai, was also connected to the cult of Mañjuśrī.

3. Robert Borgen 包瀚德 (University of California in Davis 美國加州大學戴維斯分校): “The Wutai Mountains in Classical Japanese Literature” 日本古典文學中的五臺山

China’s Wutai mountains make scattered appearances in classical Japanese literature. The earliest reference to Wutai appears in a collection of Buddhist anecdotes, compiled ca. 822, and the greatest number of references to Wutai are found in similar didactic collections. Only in modern times did this body of literature find a secure place in the classical Japanese literary canon. In the past, “literary” implied poetic and elegant, so the prosaic language of these stories and sometimes vulgar episodes that sometimes appeared with them placed these collections, at best, on the margins of the canon. In such collections, most of them compiled in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Wutai usually appeared as a place visited by Japanese pilgrims. One such pilgrim became the subject of a sequence of interrelated dance-dramas, the first of which was staged ca. 1500, with later reinterpretations appearing intermittently through the late nineteenth century. Most of these would have been considered more “popular” than “literary.” References to Wutai can also be found in more traditionally “literary” works, but they are few. For example, the mother of one pilgrim who went to Wutai mentions it in her poetic diary, and a distinguished monk, who was also known as a poet, wrote one poem on the subject of seeing Mañjuśrī at Wutai. His collected poems number approximate 6,000, suggesting how uncommon was such a reference. Although the greatest masterpieces of classical Japanese literature, both prose and poetry, are infused with Buddhist ideas, they are not didactic and make no mention of Wutai. Its appearances are primarily in less “literary” works intended to spread Buddhist faith, and they in turn influenced popular theater. Wutai thus occupies a modest place in the classical Japanese literary tradition, albeit mostly outside its mainstream. 中國的五臺山散見於日本古典文學作品之中。對五臺山最早的描述出現在一部編撰於822年左右的佛教轶聞録中,最多的關於五臺山的描述則見於類似的一些佛教善書作品中。也只是到了現代社會,這些作品方在日本古典文學經典中找到了一席安穩之地。過去,所謂的“文學”僅指那些詩體的和典雅的作品,諸如那些語詞平淡、內容粗鄙的故事作品至多被冷落在文學類別的邊緣。在這些大多編纂於十二或十三世紀的作品集中,五臺山多是被描述為日本巡禮僧的朝聖地。一位朝聖者成為了一系列彼此相關舞劇的主角,最早的一部約在1500年被搬上舞台,此後到十九世紀末期陸續被重新演繹。 大多數這類作品更多地是被看作是“民俗的”而非“文學的”。 在傳統意義上的“文學”作品中也可以找到一些五臺山的記載,但相當稀少。比如,一位五臺山朝拜者的母親就將此山寫入了詩文的日記。一位高僧,也是著名的詩人,也以在五台山親睹文殊菩薩為題創作了一首詩。而這位詩僧的詩作有大約六千首,這反襯出五台山在其詩文中的罕見性。儘管日本古典文學作品的最偉大的經典之作中,無論是散文體還是詩歌體的,都充滿了佛教觀念,但這些作品不是說教性的,也未提及五臺山。五台山主要是出現在更不具備“文學”意味但傾向於傳播佛教信仰的作品中,翻過來又影響了流行戲劇。雖然說是在主流類型之外,但是五台山在日本古典文學傳統之中仍有些許地位。

4. Isabelle Charleux 沙怡然 (National Centre for Scientific Research 法國國家科學研究中心): “Interactions between Chinese Buddhist and Tibeto-Mongol Buddhist Communities on Wutaishan: Monastic Architecture, Iconography, and Material Culture, 18th-19th Centuries” 漢人僧團與蒙藏僧團在五臺山的互動: 十八至十九世紀的寺院建築、圖像及物質文化

In the Qing and early Republican period, Wutaishan had between 25 and 30 monasteries affiliated to Tibetan Buddhism. Their monastic architecture seemed to exclusively follow the Chinese-Buddhist style, except for the Tibetan-style bottle-shaped stupa. The Wutaishan built landscape seemed relatively homogeneous, and travellers such as missionary H. Hackmann (1864-1935) were sometimes confused about the blurred visual frontier between ‘blue’ (Chinese Buddhist) and ‘yellow’ (Tibeto-Mongol Buddhist) monasteries. 在清王朝到共和國初期,五臺山大約有25至30所寺院隸屬於藏傳佛教。在寺院建築方面似乎清一色地延承漢傳佛教的規制,除了藏式的覆钵式佛塔。五臺山寺院建築風貌大體一致,諸如傳教士哈克曼(Heinrich Hackmann, 1864-1935)等人來到五臺山後會有時混淆青廟(漢傳佛教)和黃廟(蒙藏佛教)之間在視覺上的分際。

Were there buildings (other than stupas) typical of Tibetan and Mongol monasteries that have not been preserved on Wutaishan? The majority of the Tibeto-Mongol Buddhist communities settled in monastic buildings that previously belonged to Chinese communities, but at least eight Gelukpa monasteries were built anew. Why did they preserve the Chinese architectural heritage and build new monasteries following Chinese style? Was there local or imperial pressure to ‘keep things Chinese,’ or was it in their interest to entertain a visual confusion between ‘yellow’ and ‘blue’ monasteries? And how did Tibeto-Mongol Buddhist monks (lama), whose lifestyles and spatial practices of Buddhist architecture differ from Chinese Buddhist monks’ (heshang), adapt themselves to Chinese spatial arrangements? 是不是在五台山曾有典型的蒙藏佛教寺院建築(佛塔除外)卻沒有保留下來?大多數蒙藏佛教僧團都是在原本屬於漢人僧團的寺院中定居下來,但是至少有八座格魯派寺院是新建。那麼,他們為什麼要保留漢式建築遺產并且延承漢式風格來建造新的寺院呢?是否存在著來自當地或皇室的壓力,要求保持“漢家典制”?抑或是他們本身便是喜歡保持青黃寺院在視覺上的混淆?此外,蒙藏僧人(喇嘛)的生活方式和對建築的空間實踐不同於漢傳佛教僧人(和尚),那麼他們又是如何去適應漢式的空間佈局呢?

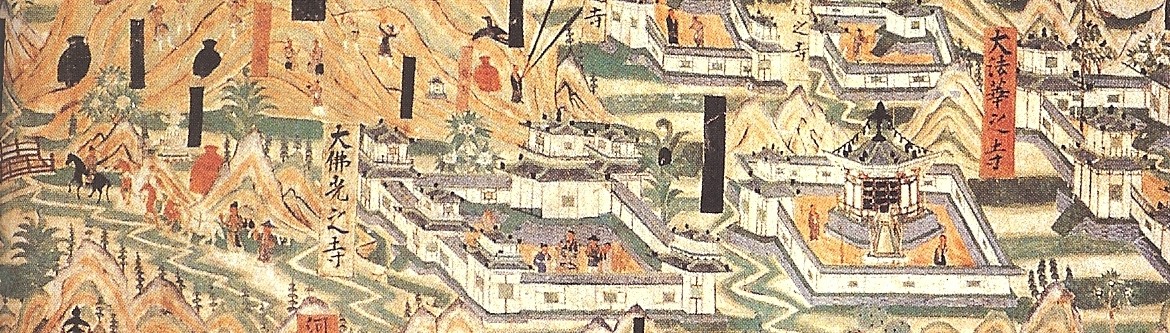

With a closer look, we can observe that there were mutual borrowings between Chinese Buddhist and Tibeto-Mongol Buddhist monasteries on Wutaishan. Using various sources such as ancient picture-maps, old photographs, floor plans and travellers’ accounts, I will highlight interactions between Chinese and Tibeto-Mongol Buddhist monasteries from the point of view of architecture, iconography and material culture in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. 仔細觀察會發現,五台山上的漢傳佛寺和蒙藏佛寺之間曾相有借鑒。通過利用諸如古地圖、舊照片、樓層平面圖等多種資料,筆者力圖從建築、圖像以及物質文化的角度凸顯在十九世紀至二十世紀早期漢傳寺廟與蒙藏寺廟之間的互動。

5. CHEN Huaiyu 陳懷宇 (Arizona State University): “A Study on the Bright-light Lamp Platform from the Guanyin Temple at Mount Wutai in Medieval China” 唐宋时期五臺山觀音寺光明燈臺考論

The lamp platform was one of the most interesting architectural designs in medieval Chinese Buddhism. Its history could be dated back to the late Northern dynasties and Shanxi area could be the place where it was invented. In the Tang dynasty, stone lamp platforms became flourishing in North China. As a Buddhist center in the medieval period, Mount Wutai attracted numerous pilgrims and it developed very rich and diverse Buddhist culture. Interestingly, one stone lamp platform from this area survived today. It was first commissioned in the Kaiyuan period in the early eighth century by a group of Buddhist adherents under the leadership of two Buddhist masters and renovated in the Song dynasty, in 997 by local Buddhist patrons. The inscription written by Zhang Chuzhen is mostly extant, which offers us an opportunity of understanding the historical context in which this platform was constructed. This paper aims to examine the significance of this lamp platform by looking into its position with a comparison with other lamp platforms discovered in Shanxi area. It will investigate the Buddhist connections between Mount Wutai and Taiyuan, as well as the Ye City by reading a group of lamp platforms in these areas as a monastic network. In the meantime, given that the Shanxi area was a stronghold of Zoroastrians from Central Asia in the medieval period as recent archeological findings demonstrate, this paper will attempt to analyze the rituals of lighting lamp platforms in Buddhism and worshipping fire temples in Zoroastrianism from cross-cultural and cross-religious perspectives. 燈臺是中國中古佛教史上最有旨趣的建築設計之一。其歷史也許可以追溯到北朝後期,山西地區也許是這一傳統的發明地。在唐代,石燈臺開始在北方流行起來。作為一個中古時代的佛教中心,五臺山吸引了無數的香客,很快發展出豐富多彩的佛教文化。有意思的是,在這一地區發現了一座石燈臺。它始建於唐代開元年間,宋代997年又由當地佛教信徒重修。唐代張處貞所寫的銘文也大多得以保存至今,使得我們有機會了解其出現的歷史語境。本文將通過將其與山西地區出現的其他燈臺放在一起做一比較以辨明其地位並理解其重要性。本文也將將這些石燈臺的建造看作是中古時期的寺院建築網絡,從而以石燈臺為例來理解五臺山與太原、鄴城等地的佛教聯繫。與此同時,鑑於近年考古發現所揭示的山西地區存在極為豐富的祆教遺跡,本文也將從跨文化和跨宗教的視角探討佛教燈臺與祆教拜火壇儀式在中古時期的儀式實踐。

6. Chen Jinhua 陳金華 (The University of British Columbia 加拿大英屬哥倫比亞大學): “Buddhapālita and the Formation of the Wutai- Mañjuśrī Cult” 佛陀波利與五臺文殊信仰的形成

The Indian monk Buddhapālita (Fotuoboli 佛陀波利) was credited not only with the transmission of a Sanskrit version of the Uṣṇīṣavijayā-dhāraṇī (one of its Chinese versions being named Foding zunsheng tuoluoni jing 佛頂尊勝陀羅尼經) to China, but also with the promotion of the Wutai-Mañjuśrī cult in East Asia. The most important textual evidence for Buddhapālita’s reputed role in the Wutai cult comes from a preface to one of the Chinese versions prepared for the Uṣṇīṣavijayā-dhāraṇī. According to this preface, it was urged by Mañjuśrī that Buddhapālita brought a copy of the Uṣṇīṣavijayā-dhāraṇī to China. This story has become an essential source for the sacredness of Mount Wutai on the one hand and the Uṣṇīṣavijayā-dhāraṇī on the other. However, another source related to Buddhapālita, a record of the meditation-related conversation between Buddhapālita and a major ideologue for Empress Wu (r. 690-705), Xiuchan yaojue 修禪要訣 (Essentials of Cultivating Meditation), casts doubt on Buddhapālita’s connections with the Uṣṇīṣavijayā-dhāraṇī and Mount Wutai. This article studies the background for the composition of this seminal but obscure/obscured text and the theories and practices of meditation represented therein. It also includes an annotated English translation for this fascinating text. 印度僧人佛陀波利(Buddhapālita)不僅有功於梵文本《佛頂尊勝陀羅尼經》(Uṣṇīṣavijayā-dhāraṇī )的傳播,且有功於東亞地區五臺﹣文殊信仰的弘揚。有關佛陀波利五臺山信仰上的角色,最重要的典據乃是一篇漢譯本《佛頂尊勝陀羅尼經》的序文。據此序,佛陀波利是受到文殊師利的敦促才將一部梵本《佛頂尊勝陀羅尼經》齎來中國 。該故事既是五臺山神聖性格的重要淵源,另一方面也是《佛頂尊勝陀羅尼經》神聖性格的重要淵源。關於佛陀波利,還有另外一部文獻,記錄著他與武則天(690﹣705在位)的一位意識形態策士關於禪修的對話,即《修禪要訣》。這部文獻使我們對佛陀波利與《佛頂尊勝陀羅尼經》以及五臺山之間的關聯提出了疑問。 本文將探討這部重要却隱晦的文獻的編纂背景,也將分析其中闡述的禪修理論和實踐。同時,本文也將為這部引人入勝的文獻提供一英文譯注本。

7. CHEN Long 陳龍 (Xinzhou Normal University 忻州師範學院/Center for the Study of the Wutai Culture 五臺山文化研究中心): 從游記文學角度看《續清涼傳》

一直以來,《續清涼傳》與《古清涼傳》、《廣清涼傳》被認為是唐宋時期重要的三部五臺山山志,合稱“清涼三傳”。對於“清涼三傳”的性質,學界一直沒有定論,不同的著錄文獻對其有不同的觀點,就“三傳”分開而言,各自的性質也不相同。總而言之,從不同的角度出發研究,可以對“清涼三傳”有不同的定性。本文從文學的角度出發,認為《續清涼傳》是一篇游記文學作品,並且是我國第一篇五臺山游記,具有獨特的藝術特色,主要體現在創作形式、表現手法、審美體驗的獨特性等三個方面。

8. DING Ming 定明 (北京佛教文化研究所): 清康熙帝的五臺山文殊信仰與蒙藏綏柔政策

清代“五臺山是國家權力的隱喻”,這一時期的五臺山佛教極其興盛,尤其是藏傳佛教,這得益于清初康熙在五臺山作為綏柔蒙藏的政策,進而重塑滿清帝王、神權、天下與開拓邊疆版圖意識。清初康熙帝之所以在五臺山文殊菩薩道場推行藏傳佛教以實現化導蒙藏歸屬滿清政權,因為清朝開國者被西藏喇嘛稱為“曼殊師利大皇帝”,對清初皇帝而言五臺山文殊菩薩道場與滿洲人的崛起有著特殊淵源。康熙在五臺山推行藏傳佛教的格魯派,迎請西藏、內蒙喇嘛主持五臺山,以此實現綏柔蒙藏的目的。此一綏柔政策一直影響著乾隆、嘉慶等清初幾位皇帝對五臺山的大力扶持,因此五臺山被營造成滿、漢、蒙、藏等各族共同尊奉的佛教聖地。

9. Yi DING丁一 (Department Religious Studies, Stanford University 斯坦福大學宗教研究系): “Translating” Wutai Shan to Ri bo Rtse lnga––Chögyal Pakpa’s (1235-1280) Introduction and Transformation of Five-Peak Mountain藏譯五臺山: 八思巴對於五臺山的引介和轉化

With the appearances of many recent studies on the activities of Tibetan Buddhism on Mount Wutai (Tib. Ri bo Rtse lnga) in the late imperial period, one question still lingers. When and how did Tibetan sacred geography become overlapped with its Chinese counterpart in the first place? In other words, who first introduced the significance of Mt. Wutai to the Tibetans with a transcultural vision? In answering this complex question, this paper aims at critically re-examining the inception of a Sino-Tibetan mountain. Despite references to Mt. Wutai in Tibetan sources compiled or reworked at a much later time, the historical presence of Tibetan Buddhism on Mt. Wutai started with Chögyal Pakpa’s (Basiba 八思巴) pilgrimage in 1257 and his related writings. Beginning with his pilgrimage and efforts to culturally “translate” Wutai as Mañjuśrī’s abode, Tibetan Buddhism gradually took root on the mountain under imperial auspices in the ensuing years. 雖然近年出現了不少有關明清時期五臺山藏傳佛教的英文著作,對作為漢地名勝的五臺山是如何進入藏傳佛教觀念之中的問題,卻少有論及。換而言之,五臺的宗教重要性是如何引介給了西藏受眾,並且藏傳佛教是如何轉化了五臺山的形象? 為了回答這個複雜的歷史問題,本文試圖從緣起的角度,來重新檢討五臺山成為一座漢藏共同認可的名勝的創造性轉化的過程。本文試圖指出,雖然在晚出的藏文材料中偶爾會出現更早的有關五臺的記錄,但是五臺山上的藏傳佛教其實起源於蒙元帝師八思巴於1257年完成的朝聖之旅以及對五臺山的詮釋。隨著八思巴對於文殊菩薩道場的認同,藏傳佛教逐漸在皇室的支持下在五臺上生根。

The first part of the paper will critically re-assess the accounts of pilgrimages to Wutai allegedly made by Indo-Tibetan masters prior to the Yüan period in Tibetan sources, such as the Testament of Ba (sBab bzhed), Blue Annals, and several hagiographies. It will be argued that these accounts are projecting a much later consciousness of Mt. Wutai’s presence into their narrative of earlier historical events, in contrast to the lack of genuine interest in Mt. Wutai in pre-13th Tibetan sources. The paper will argue that it is Pakpa who first made a historical trip to Mt. Wutai as a Tibetan master. 本文第一部分將重審藏文材料如《巴協》、《青史》、《萨迦世系》等材料中所宣稱的那些發生在元代之前的朝聖五臺的記載,并試圖論證這些有關五臺的記敘體現的是更晚的藏人地理想象中的五臺山被折射到了更早的歷史敘事之中。在檢討文本的過程中,八思巴作為首位完成了朝聖之旅的藏密大師的形象就清晰了起來。

The second part of this paper will deal with three autograph eulogies concerning Pakpa’s pilgrimage preserved in the Collected Works of the Sakya Sect (Sa sky bkaḥ ḥbum), which are Garland of Jewels: Hymns to Mañjuśrī at Five-Peak Mountain (ḥJam dbyangs la ri bo rtse lngar bstod pa nor buḥi phreng ba), Hymns to Mañjuśrī by the Meaning of his Appellation (ḥJam dpal la mtshan don gyi sgo nas bstod pa), and Garland of Flowers: Eulogy to Mañjuśrī (ḥJam dpal la nye bar bsngags pa me tog gi phreng ba). As Regent of Tibet and Kublai Khan’s royal preceptor, Pakpa successfully redefined Mt. Wutai through a Tibetan lens both for the Yüan empire and Tibetan Buddhism, by mapping the mountain in starkly Tantric terms and expounding the manifestation of Mañjuśrī from a doctrinal perspective. The politico-religious context surrounding Pakpa’s visit and its representation in later Tibetan hagiographies will also be discussed. 本文第二部分將探討收於《薩迦五祖集》中的八思巴撰的三首關於五臺山的詩文,分別是《五臺文殊頌之珠環》、《文殊名號讃》和《文殊頌之花環》。作為蒙元帝師,八思巴為他所服務的多元文化之帝國,對五臺山從藏密教理角度進行了重新定義。

The last part of the paper will be concerned with the subsequent development on the mountain in the Yüan period. Though Pakpa’s writing proposed the way in which Mt. Wutai could be incorporated into Tibetan religious imagination, it is the established of Tibetan monasteries that concretized this transcultural interpretation. Pakpa’s vision and the growing institutional connection made it possible for the Tibetans to receive the notion that Mañjuśrī resided on an exotic mountain far removed from central Tibet, which in turn encouraged later Tibetan pilgrims and prompted inspirited new imagination. 本文第三部分將探討元代藏傳佛教寺院機構在五臺山上的實現。雖然八思巴將五臺引入藏地的地理觀念之中,但是轉虛成實,仍然需要依靠藏傳佛教寺院的創建和存續。正是在八思巴的視界和寺院組織的共力之下,藏人將作為文殊道場的五臺山 納入了自己的地理體系之中,并且在藏地產生了對於朝聖五臺的持續想象。

10. DUAN Yuming 段玉明 (Sichuan University 四川大學佛教與社會研究所): 金閣天成:一座五臺山寺的興建

金閣寺位於台懷鎮西南15公裡的金閣嶺上,始建於唐大歷五年 (770)。其建寺因緣來於道義和尚的一次神聖經驗,因其或有華嚴與淨土雙重信仰背景,神聖化現出來的寺院格局具有明顯的中土寺院特色——即樓閣式寺院風格,屬於道宣所制寺院標准圖式的變形。同樣情形也見於竹林等寺的興建,証實通過“化寺”的方式為寺院空間祝聖以及格局定型或是唐時五臺山寺興建的普遍做法。這是一種前此少見的新寺祝聖方式,不止寺名、地點借此確定,即連寺院的基本格局也都大體定型,在中國漢地寺院興建的祝聖方式上頗有典型意義。至代宗時,不空請將此一神示變為現實,並由密教僧人含光、印度僧人純陀督造,格局仿照印度那爛陀寺,寺院格局由是轉成了印度寺院風格。密教影響也借此滲入了原本屬於文殊聖地的五臺山,並長期在五臺山佔據影響。就像早期塔廟格局模擬印度支提一樣,金閣寺模擬那爛陀寺亦是借此與印度神聖發生連接,由此証實寺院空間的神聖由來有自。這也是早期漢地寺院空間獲得神聖的一種方式。所以,在五臺山為自己建造一座密教寺院時,不空等人既借用了道義的神聖經驗,又接續了印度寺院的神聖,從而為密教勢力順利進入五臺山建立了合法性。既是如此,落成之寺並不是完全的印度寺院格局,中土樓閣式寺院的成分仍很明顯,金閣寺事實上成了一座中印合璧的寺院。晚唐五代寺院被毀,重建的寺院回到中土寺院風格,並演變成了淨土僧人修習的寺院。“化寺”作為金閣寺興建的一種祝聖方式,本在象征文殊“金色世界”的以銅為閣建筑方式,以及模擬印度寺院形成的接續印度正宗,其后都成了寺院興建的幾種范式。“化寺”范式成為后期寺院空間挪用的一種技巧,“金閣”范式演化出了后期佛道並有的“金殿”建筑,接續印度正宗則是日本金閣寺(又稱鹿苑寺)的神聖獲得方式。

11. Bernard Faure 佛雷 (Columbia University 美國哥倫比亞大學): De-centering Manjusri: Some aspects of Manjusri’s Cult in Medieval Japan (“去中心”文殊:中世纪日本文殊信仰的一些側面)

The “true image” of Manjusri on Wutaishan was well known in Japan as “Manjusri Crossing the Sea” 渡海文殊. Another interesting image of Manjusri, found at Tōji Monastery in Kyoto, shows Manjusri at the center of an astral diagram similar to the star mandalas popular in Japanese esoteric Buddhism. In this function as lord of the Northern Dipper and origin of all stars, Manjusri was identified with the Bodhisattva Myōken 妙見, an esoteric Buddhist version of the Daoist god Zhenwu 真武. The fierce nature of Manjusri’s lion also linked the Bodhisattva of Wisdom to uncanny deities such as Dakiniten 茶吉尼天. These symbolic links reveal Manjusri quite different from the traditional image of the Bodhisattva of wisdom. These less well-known aspects of Manjusri, however, shed retrospectively some light on the esoteric Buddhist cult of Manjusri on Wutaishan. 五臺山文殊的“真容”, 在日本以“渡海文殊”廣為人知。在京都東寺,另有一種有趣的文殊形象,它在與日本密教裡流行的星形曼荼羅相似的星狀圖形中心。文殊在此扮演著北斗星君及其他所有星相起源,被視作妙見菩薩,即道教真武大帝在密教中的對應者。文殊獅子的兇猛,也將這位以智慧著稱的菩薩與怪誕的神祇如茶吉尼天聯繫了起來。這些象徵性的聯繫,揭示了與傳統上作爲智慧菩薩的文殊的相當不同的形象。但是,文殊這些少爲人知的側面卻回溯性地提示了五臺山密教文殊信仰的新面向。

12. Imre HAMAR 郝清新 (Eötvös Loránd University, Hungary 匈牙利羅蘭大學): Khotan and the Cult of Mañjuśrī 于闐國與文殊菩薩信仰

The so-called new representation of Mañjuśrī that is found in Dunhuang and became quite popular in Wutaishan region and East Asian Buddhism includes a foreign looking person who became identified as the Khotanese king. This representation shows the close association of Khotan with Mañjuśrī and the Cult of Mañjuśrī on Wutaishan. The possible Khotanese compilation of the Buddhāvataṃsaka-sūtra, which is the main proof text for Mañjuśrī’s presence on Wutaishan and the Khotanese pilgrims to Wutaishan recorded by Dunhuang manuscripts also seem to substantiate the claim that Khotan was very important in terms of Mañjuśrī cult, and could have an important role in identifying Wutaishan as the abode of Mañjuśrī. In this paper I will show these and other proofs in Khotanese literature for the importance of Mañjuśrī in Khotanese Buddhism. 敦煌發現所謂的新樣文殊菩薩造像在五臺山地區和東亞佛教文化區域非常流行,其中有一個外國長相的人,被公認為于闐國王。此造像反映了于闐國與文殊菩薩以及五臺山文殊菩薩信仰的密切關系。于闐文編纂的《華嚴經》是証明五臺山文殊菩薩信仰的主要文本,而敦煌手稿中關於于闐國朝聖者到五臺山的記載也表明了于闐國在文殊菩薩信仰方面的重要性,這些可能為証實五臺山為文殊菩薩道場起到了重要作用。本論文將分析研究這些于闐文獻以及其他証明材料,論証文殊菩薩在于闐佛教中的重要性。

13. IWASAKI Hideo 岩崎日出男 (Sonoda Women’s University 園田学園女子大学): 文殊師利菩薩院の文殊像について」(關於文殊師利菩薩院的文殊像)

不空三蔵(704~774)は唐・永泰2年(766)の五臺山・金閣寺の建立請願以降、五臺山文殊信仰の振興を積極的に朝廷へ働きかけ長安をはじめ全国的に展開していくのであるが、このような不空三蔵の振興・展開した五臺山文殊信仰における文殊菩薩像については、その像容(姿形)が五臺山文殊像(騎獅文殊)の場合や六字文殊像の場合であるなど一様ではないことが指摘されている。今回の研究では、その振興・展開の完成ともいえる大暦7年(772)に全国寺院への設置が勅許された文殊師利菩薩院(文殊院)の文殊菩薩像の像容(姿形)について、それがどのようなものであったかを考察する。不空三藏(704-774)在唐永泰二年(766)請願建立五臺山金閣寺之後,積極向朝廷動員振興五臺山文殊信仰,(五臺山文殊信仰)從長安開始向全國展開。就不空三藏振興和展開的五臺山文殊信仰,我已經指出其文殊菩薩像的姿容與五臺山文殊像(騎獅文殊)、六字文殊像等皆不同。大曆七年(772)全國寺院敕許設置文殊師利菩薩院 (文殊院),被認為是五臺山文殊信仰振興、展開的完成,此次之研究,主要考察文殊師利菩薩院之文殊菩薩像的姿容到底如何。

14. JI Yun 紀贇 (Buddhist College of Singapore 星加坡佛學院): 五臺山國際化的關鍵性節點與要素

在中國的佛教聖山之中,五臺山的地位是超然的,並且在歷史之中,其國際化程度也遠遠超過了其他的佛教聖山。一個明顯的問題就出現了,為什麼會如此呢?本文試圖簡單討論在五臺山區域及國際影響擴張的歷史之中,所出現的幾個重要的關鍵性節點與地理要素,並同時來探討伴隨中華帝國及其文化發展嬗變的大背景之下,尤其是漢語言文化圈內部與其他語言文化圈之間交錯發展並互動之中,所體現出來的佛教歷史發展的一些規律性的東西。

15. KUAN Guang 寬廣 (King’s college, the University of London 英國倫敦大學國王學院): “The Travels of a 15th Century Abbot of Bodh Gaya: the Chakma Monk Śāriputra’s Journey to Wutai Shan” 5世紀拶葛麻王子、菩提迦耶大寺方丈——室利沙的五臺山之旅

In 1413, on a mission to Nepal, the messenger of the Ming emperor, Hou Xian, brought back an Indian Buddhist monk. This Indian monk, who was born into a royal family of East India, was known as the abbot of Bodh Gaya. Upon meeting Emperor Yongle, he presented his Chinese host with a miniature of the Maha Bodhi pagoda. In 15th century India, Islam had gained absolute dominance, so were his East Indian origin and royal background in contradiction to the belief that Buddhism had disappeared during 12th century India? This paper will trace which royal family he was born into, will investigate what caused him to leave India, what he then tried to achieve in China, and the impact he brought to Wutai Shan Buddhism. 公元1413年,永樂皇帝特使——侯顯——在出使尼泊爾的返途中帶回了一位印度僧人。這位大師出身於印度一王室,也被尊稱為菩提迦耶大寺方丈。在受到永樂皇帝接見時,獻上了菩提迦耶金剛寶塔之式。眾所周知,15世紀的印度伊斯蘭教盛行, 印度佛教受之沖擊已幾近消亡。室裡沙的東印度王室出身,和他的佛教領袖背景是否和我們所理解的佛教已於12世紀受伊斯蘭教傳入沖擊而消亡的歷史相左呢?本文就針對這一疑點展開調查,通過明朝官方史料並佛教史籍來探討室利沙大師的印度王室出身,和他迫於何種原因離開印度,他來中國之行目的,及對五臺山佛教的貢獻。

16. KWAK Roe 郭磊 (Dongguk University 韓國東國大學): 新羅中古期(514-654)五臺山文殊信仰傳來說之探討

新羅文殊信仰與五臺山文殊信仰的傳來時期不同。文殊信仰的傳來應該是早在638年慈藏入唐以前就已經通過其他求法僧隨經典的傳入而傳播開來。五臺山文殊信仰由中古期(514-654)佛教界的代表慈藏傳來之見解是韓國學界的主流,但是迄今流傳的各種慈藏相關史料中有很多互相矛盾之處,所以在復原慈藏的生平時有很多的制約。這在探討慈藏與文殊信仰的關系方面也是相同,有很多疑問需要解決。參考中國五臺山文殊信仰的成立過程可知,慈藏入唐參拜五臺山之說並不成立。那麼史料中的慈藏與五臺山文殊信仰相關內容的出現背景及原因值得引起我們的註意。它是何時出現的?為什麼會出現?本文將對其出現的社會思想背景做一番探討。

17. George KEYWORTH 紀強 (Linguistics and Religious Studies, University of Saskatchewan 加拿大薩斯喀徹溫省大學語言與宗教研究系): How the Mount Wutai Cult Stimulated the Development of Chinese Chan in Southern China at Qingliang monasteries五臺山信仰如何激發禪宗在南方清涼寺的發展

Despite the legendary role ascribed to Shaolin monastery 少林寺, located near Mount Song 嵩山, it is probably not an exaggeration to say that it has been considered sacrosanct within Chinese Chan Buddhist discourse since at least the time of Heze Shenhui 菏澤神會 (670-762) that legitimacy comes from the south, and not the north. Since the 10th century, the rhetoric of the so-called “five schools” 五家 has perpetuated peculiarly southern lineages; in practice, both the Linji 臨濟宗 and Caodong 曹洞宗 lineages (in China and beyond) propagate stories of celebrated patriarchs against a distinctively southern Chinese backdrop. What are we to make, therefore, of Chan monasteries or cloisters in Ningbo 寧波, Fuzhou 福州, Jiangning 江寧, and of course, Hongzhou 洪州 (Jiangxi province 江西省), apparently named to reflect the enduring significance of Mount Wutai 五臺山, a notably northern sacred site? In the first part of this paper I outline the less than marginal—or peripheral—role Mount Wutai appears to have played in “core” Chinese Chan Buddhist sources (e.g., denglu 燈錄, yulu 語錄, and gazetteers 地方志). Then I proceed to explain how four Qingliang monasteries 清涼寺 (or cloisters 院) in southern China attest to the preservation and dissemination of a lineage of masters who supported what looks like a ‘Qingliang cult,’ with a set of distinctive teachings and practices that appears to collapse several longstanding assumptions about what separates Chan 禪 from the Teachings 教 in Chinese Buddhism. Finally, I address the implications of a Chan Buddhist ‘Qingliang cult’ within the context of the history of Wutaishan after the 13th and 14th centuries, when the site had become a destination where Tibetans, Tanguts, Mongolians, Manchurians, Koreans, and southern Chinese pilgrims sustained veneration of Mañjuśrī or Mañjughoṣa. 位於嵩山附近的少林寺具有其傳奇的角色。儘管如此,以下的說法也許並不為過: 在禪宗話語中,至少從菏澤神會(670-762)時代開始,禪宗的正統來自南方而非北方,這是神聖不可侵犯的。自十世紀始,所謂“五家”的說辭便一直延續著南宗法脈;而實踐中,中外臨濟宗和曹洞宗的傳承都將著名禪師的故事放在南方的獨特背景下加以宣揚。寧波、福州、江寧,當然還有江西洪州等地的禪寺的名字中卻反映出五台山這一北方聖地的持續重要性,我們又作何理解呢?首先,筆者將大致概述一下諸如燈録、語錄、方志等禪宗核心文獻中五臺山的甚至算不上邊緣性的角色;接下來,筆者也會解釋位於中國南方的四座清涼寺(院)如何見證了弘揚“清涼崇拜”的一脈師資的傳承;他們的那套教義和實踐可能會瓦解幾個長久以來關於“禪”與“教”分野的預設。最後,筆者將在十三、十四世紀五台山史的背景中探討“清涼崇拜”的影響; 此時五臺山已成為了西藏、蒙古、滿洲、朝鮮以及中國南部地區的朝聖者維持文殊或妙音崇拜的聖地。

18. Youn-mi KIM 金延美 (Yale University 耶魯大學): Surrogate Body inside a Statue: Later Mañjuśrī Worship on Korea’s Wutaishan (Odaesan) 神像中的替身:韓國五臺山的晚期文殊師利信仰

The origin and the early history of Mount Odae, the Korean version of the sacred Mount Wutai, have drawn much scholarly interest. According to the well-known legend, the Silla monk Chajang (590-658) initiated the belief that Mount Odae is the abode of Mañjuśrī Bodhisattva. While the origin history of this sacred mountain from the Silla dynasty is important, the diverse practices and the rich visual culture that developed in later dynasties are also worthy of in-depth exploration. In fact, Mount Odae was a vital center of Buddhist practice even during the Chosŏn dynasty (1392-1897), a time when Buddhists were severely persecuted. Perhaps the most intriguing Buddhist relic from Mount Odae is the wooden statue of Mañjuśrī (1466) at Sangwonsa. In 1984, various materials were found enshrined inside this Mañjuśrī statue. Beyond the sacred objects and scriptures enshrined to enliven the images, such as a crystal jewel and printed book with dhāraṇī written in Korean script, there were articles of clothing smudged with blood and sweat stains. Tracing the medical and religious practices of Chosŏn Korea, this talk examines how the clothing stained with bodily fluids served as the surrogate body of a donor in Chosŏn, and how this surrogate body still engenders the modern myth about the king’s body and disease in contemporary Korea. 韓國版的五臺山的起源及其早期歷史已經得到了眾多學者的關注。根據那個著名的傳說,新羅僧慈藏(590-658)最早宣揚了韓國五臺山即是文殊菩薩道場。雖然這座山在新羅朝的起源非常重要,但是後續王朝時期出現的諸多宗教實踐以及更豐富的視覺文化也相當值得深究。事實上,在佛教被酷烈迫害的朝鮮王朝(1392-1897),韓國五臺山也是一個充滿活力的佛教實踐中心。其最著名的佛教聖物可能即是上原寺的木質文殊師利像(1466)。1984年,在文殊木質像中發現了許多文物。除了許多使佛像具有靈性的聖物和經典,諸如水晶珠寶和印製的帶有韓書陀羅尼的書本等,還有帶有血跡和汗漬的衣物。通過追溯朝鮮王朝時期的醫療和宗教实践的歷史,本文將會檢討帶有體液的衣物如何成為施主的“替身”,這種“替身”又如何引發了當代韓國對國王身體和疾病的神話。

19. LIN Wei-cheng 林偉正 (University of Chicago 芝加哥大學): “Beyond Iconography: Mañjuśrī Riding a Lion and the Cult of Mount Mutai” 圖像學之外: 文殊騎獅圖像和五臺山文殊信仰

Few would disagree that the image of Mañjuśrī mounted on his lion is the most representative iconography associated with the cult of Mount Wutai throughout the history of the sacred mountain in northern China. Yet probably more than many have realized is just how pervasive and consistent the iconography had been, not just at Mount Wutai but elsewhere in regions to which the sacred mountain cult was transmitted. By no means did the significance, interpretation, or function of the image remain the same over the long history of the cult, but its visual form and features (more complicated than those of a usual seated Buddha or standing bodhisattva) seem to have been peculiarly enduring when considering how widespread the sacred mountain cult was practiced and how much the image was appropriated for different sectarian purposes or ritual functions. The ubiquity of the iconography unbound by the sacred site is all the more extraordinary should we be reminded that Mañjuśrī riding a lion, unlike other buddhas or bodhisattvas, is supposed to be seen only at Mount Wutai. Not taking the iconography’s longevity simply as part of the cultic popularity, this paper argues that Mañjuśrī riding a lion in fact provided a convenient, yet critical, visual device, or strategy, that helped negotiate the understanding of the sacred mountain cult, e.g., its divinity, sacrality, iconography, soteriology, etc., outside its place of origin. Beyond iconography, therefore, the legacy of Mañjuśrī riding a lion should reveal to us its iconographic mechanism and economy (i.e., its functions and meanings) developed vis-à-vis the history of the sacred mountain cult. 在五臺山文殊信仰發展的歷史中,文殊騎獅像一直是其最重要的圖像﹔但這個圖像的一致性和普遍性卻是超乎想象的,這不但是在五臺山,在五臺山之外許多文殊信仰傳播的區域亦是如此。相同的圖像在不同的時期和區域可能產生不同的圖像意義、解釋、或功能﹔但文殊騎獅圖像的形式和特征(比起一般單純的坐佛或站立菩薩來的復雜)卻是無比尋常地持久,就算圖像語境和時空都已不再相同。如果我們再考慮到文殊騎獅的化現,按理隻應出現在五臺山,文殊騎獅像不受特定地域限制的特性,就顯得更加特殊。本報告認為五臺山文殊信仰廣泛的傳播隻是其圖像持久不變的原因之一,最主要的還是因為文殊騎獅像元素本身在傳遞五臺山信仰內涵所具有的圖像張力和可塑性。因此,文殊騎獅像的研究應該是超越圖像學的領域,本報告將探究文殊騎獅圖像的功能和其圖像持久性之間的關系,希望進而揭示文殊騎獅圖像在五臺山文殊信仰傳播中的運作方式和宗教效益。

20. David Quinter 蒯恩特 (University of Alberta 加拿大阿爾伯塔大學): “Moving Monks and Mountains: Chōgen and the Cults of Mañjuśrī, Wutai, and Gyōki” 轉進中的僧侶與山嶽: 重源與文殊師利、五臺山及行基崇拜

The itinerant Shingon monk and Pure Land devotee Chōgen 重源 (1121–1206) presents many puzzles to researchers. In addition to his spearheading the restoration of Tōdaiji and its Great Buddha statue after their burning in 1180, Chōgen’s renown has rested greatly on his self-professed three pilgrimages to China. However, scholars have long questioned the reliability of Chōgen’s accounts, with some doubting that he ever went. The current majority view, based largely on pairing Chōgen’s own accounts with the material evidence for his links to Song artisans and construction techniques, is that he did make the trip. But doubts linger concerning many of the details Chōgen claims, not least of which is his professed veneration of Mañjuśrī at Mt. Wutai. 重源(1121–1206)是一位四處漂泊的真言宗僧人,也兼習淨土。對於研究者而言,他可謂謎影重重。東大寺及其大佛像於公元1180年被焚毀後,重源曾首倡復建。此外,關於他的最為宏偉之績莫過於他自稱曾三次前往中國朝聖。不過,長久以來學界對他這番表述頗存疑慮,更有甚者還有人懷疑他是否真得曾涉足過神州。目前的主流意見,主要是將重源自己的敘述,與他和宋朝工匠之間的聯繫以及建築技藝等實質性證據加以比較,并得出結論他確曾前往。但是關於重源所號稱之事,有很多細節之處仍疑慮重重,其中很重要的就是他號稱曾前往五臺山朝拜文殊師利。

In one of the leading contemporary sources for Chōgen’s three journeys to China, an 1183 dialogue with the influential courtier Kujō Kanezane 九条兼実 (1149–1207), Chōgen is quoted as stating that his “original intention for crossing the seas had been in order to pay reverence at that mountain [Wutai].” However, he had to return to Japan without doing so, because “Mt. Wutai had been taken over by the Great Jin country 大金國.” This account fits the historical record in that, at the time, the Jin had taken control of northern China, including Mt. Wutai and the surrounding area. This made travel there from the Southern Song very difficult—and likely even more so for a Japanese pilgrim such as Chōgen. Yet Chōgen’s report to Kanezane is apparently contradicted by his own words a mere two and a half years later, in an 1185 vow he offered when relics were inserted in the restored Great Buddha statue. In the vow, Chōgen claims that he had in fact been able to make it to Wutai and “pay reverence to Mañjuśrī’s auspicious light.” But given that we have no records (self-reported or otherwise) of Chōgen traveling to China between 1183 and 1185, that the Wutai area remained under Jin control during that time, and that Chōgen’s intense involvement with the Tōdaiji restoration would have made a journey to the mountain then particularly unlikely, how are we to understand the incongruity between these two accounts? 在當時,重源曾三次前往中土朝聖的最為重要的資料之一,就是在公元1183年他與權貴九條兼實(1149–1207)之間的一段對話。在此對話之中,重源提到他“跨海之本願是為致敬[五臺]山。”不過,他卻未能如願就返回了日本,因為“五臺山已入大金國之手”。此條與歷史記錄完全相符,此時大金已然佔據華北,其中也包括五臺山及周邊地區。這就使得從南宋前往此地萬分困難——而一位如重源這樣的日本朝聖者想要前往,恐怕就會難上加難。不過,重源告九條兼實之語,很明顯與僅僅兩年半後重源自己的話有矛盾之處。這段話存於公元1185年,為重建的大佛像內裝填舍利的一則願文之中。在此則願文裡,重源號稱他其實曾到過五臺,並曾“禮敬文殊師利靈光”。不過,因為我們找不到重源曾於公元1183-1185年前往中國的任何記錄(無論是他自己所言還是其他材料),此時的五臺地區還是大金國疆域,並且重源正忙於東大寺的重建,這也讓他前往五臺山朝聖變得非常不太可能,那我們又如何來理解在這兩類記錄之中的矛盾之處呢?

This paper will explore the incongruity and scholarly attempts to address it by contextualizing it within Chōgen’s mountain pilgrimage practices and his participation in the linked—but distinguishable—cults of Mañjuśrī, Wutai, and Gyōki 行基 (668–749). In so doing, I will argue that questions of how Chōgen may have venerated Mañjuśrī “at Wutai” require more than tests of historical veracity to properly address. I suggest instead that the “fit” and “no-fit” of the moving cultic and historical puzzle pieces themselves are keys to understanding how Chōgen places Wutai and his itinerant practices within broader cultural imaginaries. 本文將要探尋這種不協調之處,并試圖將此問題放在一個大背景之中加以處理。此背景就是重源的朝山行履,以及他置身其中的文殊師利、五臺山與行基(668–749)崇拜,這些崇拜之間相互聯繫,卻又清晰可辨。通過此一研究方法,我會指出重源如何才能“在五臺山”上禮敬文殊師利的這些問題,與其我們探究其歷史上的真實性,更需要的其實是適當的處理方式。我認為與其將這些文化與歷史的拼圖一片片地用“適用”與“不適用”來加以衡量,關鍵還在於要去理解重源是如何將五臺山以及他的遊方行止放在一個更為廣大的文化圖景之中加以理解。

21. NENG Ren 能仁 (Chinese Research Institute for Buddhist Cultures 中国佛教文化研究所):元世祖忽必烈與五臺山佛教

經歷宋、金的沉寂之後,元代五臺山佛教迎來一個新的發展時期,這與元初世祖忽必烈對五臺山佛教的支持息息相關。忽必烈對漢、藏佛教皆有濃厚的興趣,其接受薩迦法王八思巴灌頂,尊奉八思巴為帝師,統領天下佛教,促成了藏傳佛教真正進入五臺山的機緣。作為蒙古族皇帝,忽必烈措意調和聖地五臺山漢、藏佛教的發展,這也成為他融合漢藏佛教信仰和整合漢、藏、蒙等多民族關係的一個重要範本。

22. James ROBSON 羅柏松 (Harvard University 哈佛大學): “From the Purple Palace of Transcendents to the Abode of Mañjuśrī: What Can We Know About Wutaishan’s Pre-Buddhist Religious Landscape?” 從仙人紫府到文殊道場:對於前佛教時代的五臺山宗教景觀我們能知道些什麼?

It has become increasingly clear that the history of how Buddhists established a sacred geography in China—particularly in their selection of sacred mountains—is largely a story about how they incorporated pre-existing sacred sites. Prior to Wutaishan’s rapid ascent as one of the most significant Buddhist sacred mountains throughout Chinese history it had already been a site connected with pre-Buddhist religious traditions (especially Daoism). Indeed, before becoming the glorious abode of Mañjuśrī and an international pilgrimage center, it was the home to Daoist transcendents. We are already aware of some suggestive references to Daoism found in the Gu qingliang zhuan 古清涼傳 [Old Account of (Mt.) Qingliang], but in this paper I hope to be able to bring together further information about what we can know about the earliest strata of Wutaishan’s religious history. What significance can we draw from the history of Wutaishan’s pre-Buddhist history? Was that earlier history overwritten or erased in later histories of the mountain? 有一點已經越發清晰了,即中國佛教建立其神聖地理──特別是選擇其聖山——的歷史,很大程度上就是一個如何吞併先前聖地的故事。在五臺山迅速崛起為貫穿中國佛教史的最重要的聖山之前,五臺山已然成為前佛教時代宗教聖地(尤其是道教)。的確,在成為輝煌的文殊道場以及國際性朝聖中心之前,五臺山早已是道教仙山。在《古清涼傳》中我們可以找到一些暗示性的信息可以證明道教的早期存在。但是在本文中,筆者更希望搜集更多信息以了解五臺山宗教歷史的最早期積層。從五臺山前佛教的歷史中,我們又可以得出什麼樣的重要認識?在後期的關於本山的歷史中,五臺山的早期歷史是被言過其實了,抑或被抹殺了呢?

23. SEOK Gil-Am 石吉巖 (Research Institute for Buddhist Cultures, Geumgang University 韓國金剛大學佛教文化研究所): 韓國五臺山聖地的形成與中國五臺山

本文就韓國五臺山聖地的形成過程中中國五臺山聖地信仰對其產生了怎樣的影響做了考察。特別是新羅僧侶慈藏把中國五臺山信仰移植到新羅的過程中,考察古代國家佛教成立的一個過程。在慈藏以後所進行的聖地化過程中,新羅王室與之有著重要的關聯,這說明新羅五臺山聖地的形成是以國家佛教為其背景的。中國五臺山文化的新羅傳播不但要考察佛教聖地信仰的東亞傳播之過程,還要對其社會思想背景做一番探討。

24. SHENG Kai 聖凱 (Tsing-hua University 清華 大學): 地論學派與五臺山佛教

五臺山在北魏、北齊時代形成第一個興盛時期,地論學派作為北朝佛教最為活躍的學派,與五臺山佛教有密切的關聯。地論學派的律學傳承於五臺山的法聰、道覆,慧光、曇隱師事道覆;靈辨作為五臺山最早傳習《華嚴經》的高僧,著《華嚴論》一百卷;地論師祥雲、曇義、曇訓等,皆修道、弘法於五臺山。五臺山既是地論學派律學傳承的發祥地,更是地論師修道、弘揚《華嚴經》的聖地。

25. Barend TER HAAR 田海 (Oxford University 牛津大學): “The Way of the Nine Palaces and the Mountain of the Five Platforms (Wutai shan): Thinking through Our Analytical Categories” 九宮之道與五臺之山:透析當前學界的分析範疇

The movement that I will focus on in this paper is known as the Way of the Nine Palaces (jiugong dao 九宮道). It was founded, of that is the right word, in the early 20th century by a monk on the mountain of the Five Platforms. While largely unknown in Western scholarship, it is invariably studied today in Chinese scholarship in the context of secret societies (mimi jieshe 秘密結社, ironically a term first coined in the 19th century by a Dutch sinologist, G. Schlegel) or the “Gatherings, Ways and Gates” (huidangmen 會道門). In earlier research I have already argued that research on new religious movements in China has suffered from negative labelling, which has skewed our perspective on creative new religious developments. Since this particular movement has been relatively well-studied from an empirical point of view, I want to reinvestigate the appropriateness of traditional labels, but also and more importantly what we can learn on local religious creativity from this particular case. 本文所關注的是一個名為“九宮道”的運動。九宮道是20世紀早期在五臺山由一位僧人所成立的,如果可以用“成立”一詞的話。在西方學界,這一運動不為所知,而在今天的中國學界,它卻總是被放在“秘密結社”或者“會道門”的範疇中來研究。(有意思的是,秘密結社一語在19世紀被一位荷蘭的道教學者G. Schlegel所首創)在早先的研究中,我已經論述,對中國新型宗教運動的研究受制于負面標識,致使我們審視具有創造性的宗教新發展的視角出現偏差。因為對這一宗教運動已有實證式的比較不錯的研究成果,本文則重新檢討一直以來給它的標籤的合理性,更重要的是探討我們從這一案例中能獲取什麼關於地方宗教的創造力新的認識。

26. SUN Yinggang 孫英剛 (Fudan University 復旦大學):文殊信仰与王權觀念:從内亚到東海

本文將討論文殊信仰從中亞傳入中土的演進過程中,在政治思想和政治實踐中扮演的角色,尤其是跟密宗有關的護國思想。通過文殊及五臺山在政治起伏中的角色,討論文殊信仰在整個亞洲史圖景中的位置。除了討論外來宗教因素和本土政治運作的關係之外,本文還將梳理文殊信仰在佛教在亞洲大陸興起傳播中的地位和作用。

27. Temur TEMULE 鐵木勒 (Nanjing University 南京大學): 傳教士景雅各對五臺山的探訪

景雅各(James Gilmour,1842-1890)是倫敦會傳教士,從1870年到1890年堅持在蒙古人中傳教,時間長達20年。在倫敦會歷史上,他應該是最著名的傳教士之一。他之所以如此著名,首先是因為歐洲人關於蒙古高原嚴酷環境的想象,其次是由於景雅各失敗的傳教事業:20年的傳教工作沒能勸化一個蒙古人皈依基督教。擋在景雅各面前的銅牆鐵壁就是蒙古人篤信的藏傳佛教。為了深入了解蒙古人的宗教信仰,他和艾約翰(John Edkins)一同探訪了蒙古人朝拜的佛教聖地五臺山。在此,景雅各對五臺山的寺廟、喇嘛和蒙古人的朝拜活動進行了細致描畫。這在同時期漢文和蒙古文材料中都是難得一見的。

28. USUI Junji 薄井 俊二 (Saitama University 埼玉大学): 旅行日記における五臺山―円仁と徐霞客 (旅行日記中的五臺山——圓仁與徐霞客)

同じ山であっても、立場が異なる人が見ると、違うものが見える。本報告では、仏教者であった唐時代の円仁と、山川自然の探索者であった明時代の徐霞客という立場の異なる人が書いた「旅行日記」を取り上げ、そこにどのようなことが記されているかを検討する。彼らは五臺山で何を見、どんな体験をしたのか。また、五臺山をどのようなものと捉え、どのように描いたのか、を明らかにする。即使是同一座山,立場不同的人,所見亦不同。本報告選取作為佛教徒的唐代圓仁與山川自然探索者的明代徐霞客兩位立場不同的人所寫的“旅行日記”,研究其中所記錄的到底是什麼。他們在五臺山到底見到什麼,有何等的體驗?同時弄明白他們抓取了五臺山的哪些面相,如何描摹的。

仏教者の円仁にとって五臺山は「聖地」であった。そこで円仁は「入唐求法巡礼行記」の中で、五臺山山中を巡礼し、その聖地性に着目した記述をしている。一方山川自然の探索者であった徐霞客は、「遊五臺山日記」の中で五臺山の自然について多く描写している。中でも山脈や水脈を描くことを重視しているが、それは彼が大地には「連続性を持つ」「脈」が走っていると捉えており、山や水はその「脈」の現れだと考えていたことによる。對於作為佛教徒的圓仁而言,五臺山是“聖地”,在《入唐求法巡禮記》中,圓仁巡禮五臺山,著眼於其聖地性進行描述。另一方面,作為山川自然探索者的徐霞客,在《遊五臺山日記》中,大量描寫五臺山的自然風貌,重視描寫山脈、水脈,是因為他認為大地“擁有連續性”,沿“脈”貫通,而山、水正是這種“脈”的體現。

29. WANG Song 王頌 (北京大學哲學系): 舊跡新禮:近代日本學者對五臺山佛教的考察

作為東亞佛教圈的著名聖地,五臺山自古就受到日本佛教界的高度重視。中古時代圓仁、成尋等人的巡禮已廣為人知,而近代日本學者、僧人對五臺山的考察卻並不為人所熟悉。事實上,在近代中日兩國國際地位逆轉、西方學術方法為日本學者所廣泛採用的歷史大背景下,近代的考察與古代的巡禮有同有異,可謂之“舊跡新禮”。本文將重點介紹伊東忠太、小野玄妙、常盤大定(常盤本人的踏查並未涉足五臺山)等人對五臺山的實地考察與文字著述,並結合其歷史背景予以分析。本文是筆者有關近代歐美日本學者考察中國佛教史跡系列研究的一環,其著眼點有三:一是瞭解清末民初中國佛教史跡保存的狀況;二是借他人之眼發現中國佛教聖地的價值和意義;三是考察近代東西方文化與宗教的交流和碰撞。

30. Dorothy WONG 王靜芬 (University of Virginia 弗吉利亞大學): “Iconography of the Wonder-Working Mañjuśrī” 作為施神蹟者的文殊菩薩其圖像考釋

We are familiar with the East Asian depiction of Mañjuśrī Bodhisattva riding a lion, or of the other type depicting Mañjuśrī as a young prince holding his emblems of a sword and a book (the Prajñapāramitā Sūtra), usually found in South Asian and Himalayan traditions. The lores of Mañjuśrī include the bodhisattva manifesting as an old man, a wretch, and so on. This paper explores how the iconography of Mañjuśrī Bodhisattva emerged in early Buddhist art, both in Indian and East Asian traditions. It examines a number of early texts, including proto-Avataṃsaka sūtras, the Avataṃsaka sūtras as well as other relevant Mahāyāna texts in which Mañjuśrī makes his presence felt—texts that contributed to the development of the cult of Mañjuśrī. It also identify the ways with which Mañjuśrī is represented in early Buddhist art in order to achieve a visual identity distinct from (and often in competition with) other Great Bodhisattvas of the Mahāyāna, such as Maitreya and Avalokiteśvara. 我們一般都熟悉文殊菩薩在東亞藝術中騎獅的形象,或是以年輕的王子形象出現,手持劍與書(《般若經》)作為圖像標誌;後者一般在南亞和喜馬拉雅地區的藝術傳統中表現。此外,有關文殊的傳說,也包括菩薩化身為老人或貧婦等等。本文旨在探討有關文殊菩薩的圖像在早期佛教 (無論是在印度或東亞的傳統)藝術中在何種情況下出現 。它考察了一些早期的文本,包括屬原華嚴經類(proto-Avataṃsaka)的經文,《華嚴經》,以及其他相關的大乘佛教經文等。這些文本是文殊菩薩信仰形成的依據。本文還確定文殊菩薩在早期佛教藝術中如何建立其與不同的視覺形象,以區別於(并往往相競爭於)大乘其他大菩薩,如彌勒菩薩、觀音菩薩等。

31. WU Shaowei 武紹衛(首都師範大學歷史系):唐五代五臺山文殊信仰傳播路線——以巡禮五臺山和“化現”故事為中心

唐五代時期高僧巡禮五臺山,是中古時期五臺山文殊信仰傳播的重要路徑。而五臺山文殊化現故事則是巡禮五臺山的信眾所要親見親聞的,也是五臺山文殊信仰的重要表現形式。通過對高僧巡禮和化現故事進行歷史學的分析,可以發現五臺山文殊信仰的傳播可以分為三個階段,即唐前、唐初和中晚唐以後。三個階段呈現出不同的宗教面貌,這種面貌和文殊信仰的階段性特徵相符合的。第一階段五臺山文殊信仰局限在五臺山及其周邊地區,更多的是一種地域性信仰;第二階段在官方主導下出現了一次巡禮高潮,高潮的起點正是長安;第三階段則呈現出巡禮者源自全國的特徵,各宗元匠巡禮五臺山、營造化現故事,引導了這一時期信仰發展方向。對北朝以至五代時期五臺山文殊信仰進行總體上的把握,可以看出,在《華嚴經》的敘述下,五臺山成為了與經典話語相一致的中華聖山,但影響有限;經過來自長安城的政治推動,遂成為了天下的信仰聖地。

32. YANG Xiaojun 楊效俊 (陝西省博物館副研究員): 五臺山地方唐代佛教造像和長安樣式的關係

唐代五臺山的地理范圍包括今山西省五臺、繁峙、忻州、代縣、阜平等地區。從五臺山佛光寺、古竹林寺、忻州等地出土石造像和南禪寺(782)、佛光寺(856)現存彩繪塑像可一窺唐代五臺山地方佛教造像的類型、圖像和風格。五臺山地方唐代佛教造像的圖像和風格受到長安樣式的影響,但是具有獨特地域特色,顯示出和天龍山石窟造像及定州風格的相似性。推測其原因在於唐代五臺山與長安之間的佛教網絡中長安高僧頻繁來往於兩地,長安高僧造像依據長安圖像和風格就地取材造像,因此五臺山的地域風格得以形成和延續。南禪寺和佛光寺彩繪塑像直接受到形成於印度八、九世紀形成的巴洛克風格的影響,呈現出裝飾性、運動感和個性化的特征,形成了五臺山地方獨特的佛教殿堂視覺文化,表明九世紀五臺山已經成為國際化的佛教中心和聖地。

33. Mimi YIENGPRUKSAWAN 楊靡蕪 (Yale University 耶魯大學): “Mañjuśrī’s Many Marvels: On the Wutaishan Phenomenon in Eleventh-Century Japan from a Regional Perspective” 文殊師利顯聖:方域研究視野中的十一世紀日本的五臺山現象

It is often assumed that the Japanese monk Chōnen 奝然 (938-1016) traveled to China in 983 to obtain a statue replicating the Udayana Buddha. However contemporary sources make it clear that Chōnen’s stated goal was to make a pilgrimage to Wutaishan and, in so doing, to lay the groundwork for the foundation of a surrogate Wutaishan on Mount Atago 愛宕山 in Kyoto. On his return to Kyoto in 987 Chōnen filed a petition with the Council of State to establish Godaisan Seiryōji 五臺山清涼寺—Wutaishan Qingliangsi—on Mount Atago, with its own ordination platform, and a hall for the Udayana image that he had obtained in Taizhou. The center would house five monks titled Godaisan Ajari 五臺山阿闍梨, or Wutaishan Preceptors, whose duty was to pray to Mañjuśrī on behalf of the country. The petition was denied due to opposition from the Tendai establishment on Mount Hiei. In 988, while negotiations over Mount Atago continued, Chōnen sent his disciple Ka’in 嘉因 (act. late 10th-early 11th century) back to China to obtain a statue of Mañjuśrī along with newly translated texts. By the time that Ka’in returned with the statue of Mañjuśrī in 990, the old temple Seikaji 栖霞寺, on the eastern slope of Mount Atago, had been revamped to serve as the home for the Udayana image and to house the single monk who had been granted the title Godaisan Ajari, meaning that the temple now served as the head institution of a Japanese Wutaishan. The Chinese statue of Mañjuśrī was placed in the care of Fujiwara no Michitaka 藤原道隆 (953-995), one of the sponsors of Chōnen’s pilgrimage to Wutaishan, and ended up remaining in the private Mañjuśrī chapel of the Fujiwara family until 1053, when it was moved to the newly built Tripiṭaka Hall at Byōdōin 平等院. The efforts of Chōnen’s disciple Jōsan 盛算 (act. late 10th-early 11th century), in close affiliation with the Fujiwara leadership, vouchsafed the further development of Seikaji as a center for Mañjuśrī worship in Kyoto, including assignment of the full contingent of five Godaisan Ajari to the temple. In 1031 another statue of Mañjuśrī arrived with much fanfare in Kyoto, along with more texts and a number of xylographic prints. The statue had been obtained for Jōsan by the Mingzhou merchant Zhou Liangshi 周良史 (act. early 11th century). It was installed at Seikaji, and shortly afterward the temple’s name was changed to Seiryōji, or Qingliangsi. 關於日本僧人奝然 (938-1016),一般認為他983年往中國一行是為了獲取一尊優填王佛像的複製品。但是當時的記載中,奝然明確聲明此次中國之行是朝拜五臺山,並為將京都愛宕山打造成日本版的五臺山作鋪墊工作。 987年奝然回到京都後,他便向太政官申請在愛宕山上建造五臺山清涼寺,並建立戒壇和一個大殿以供奉他從台州請來的優填王佛像。 這一佛教中心將安置五位僧人,冠以五臺山阿阇梨的頭銜,其職責則是向文殊師利為國祈福。 這項申請被拒絕了,因為受到了比叡山天台宗的反對。 988年,愛宕山的事情仍在協商之中,奝然派遣弟子嘉因再往中國,迎請一尊文殊師利造像和新譯經典。等到嘉因將文殊像請回的990年,位於愛宕山東坡的栖霞古寺以得以修繕,成為優填王像的本寺,並有一位持有“五臺山阿阇梨”頭銜的僧人住持。這說明這座寺廟已經成為日本五臺山的首要機構。由中國請來的文殊像則寄供在藤原道隆 (953-995)那裡,他是奝然朝拜五臺山的資助人之一;後來這尊文殊像保存在藤原家族的私家文殊廟里,一直到1053年又被移請到新建的平等院三藏堂。奝然弟子的努力,通過與藤原氏的領導力相結合,保證了栖霞寺進一步發展為文殊崇拜在京都的中心,栖霞寺也因之具足五位“五臺山阿阇梨”。在1031年,京都隆重地迎來了另一尊文殊像,以及一些經典和雕版印刷物。這尊文殊像是明州的商人周良史(活躍于11世紀)為盛算請得。這尊像被供奉在栖霞寺,不久這座寺廟便更名為清涼寺。

Seiryōji has been understood almost exclusively in terms of the Udayana cult in Japan or as the function of a geomorphological “Wutaishan” space in this case mapped onto Mount Atago. Both approaches have great merit. However they do not address the underlying rationale, which points specifically to Mañjuśrī, and to the efflorescence of ritual and devotional activities directed toward Mañjuśrī in Kyoto in the first decades of the 11th century. So significant was this turn that the conceptual and iconographical program of Fujiwara no Yorimichi’s 藤原頼通 (992-1074) famous Amitābha Hall at Byōdōin—the Phoenix Hall—finds its impetus to some degree in visionary encounters with Mañjuśrī on Wutaishan, and thus is closely integrated with Ka’in’s Chinese statue of Mañjuśrī installed in the Tripiṭaka Hall built nearby. These complex interconnections point to a topic that has been little studied, and that is the nature of the acute interest in Mañjuśrī and Wutaishan evident in Kyoto at the turn of the 11th century. This paper seeks to integrate insights from three angles of approach. First, it looks at the expectation that the final demise of the Dharma was to commence during the 11th century, and at the exogenous environmental (specifically epidemiological) factors that might have prompted such thinking in Kyoto in the period 995-1025. Second, it considers the possibility that Tianxizai’s recent recension (ca. 983-1000) of 28 sections of the Mañjuśrīmūlakalpa (T1191 文殊師利根本儀軌經)—with its emphasis on the transformative powers of spells associated with or taught by Mañjuśrī, and on identification of the geographical zones where such rituals “work”—was known in Kyoto despite its non-canonical status at the time. And third, it explores the role of Wutaishan, Mañjuśrī, and Tianxizai’s recension of the Mañjuśrīmūlakalpa in contributing to the notion of Buddhist oikumene. 一般總是把清涼寺僅僅與日本的優填王崇拜聯繫在一起,或者將其看作是愛宕山改塑為五臺山的一種努力。兩種視角均有其優勢。但是兩者都沒有觸及一條潛在的基本原則;該原則特別指向文殊師利,以及11世紀最初幾個十年之間在京都盛極一時的針對文殊菩薩的宗教儀式和崇拜活動。這一轉變意義非常,藤原頼通(992-1074)對平等院阿彌陀堂(鳳凰堂)的概念和圖像規劃在某種程度上受到五臺山文殊顯聖的經歷的激發,因此與嘉因從中國請來的文殊像密切相關,後者就安置在建造于附近的三藏堂。這些複雜的聯繫指向一個鮮為研究的課題,即在11世紀初的京都出現的對文殊師利和五臺山強烈興趣的性質。本文旨在整合三種視角的洞見。第一,本文探討一個觀念,即佛法在11世紀開始走向最終的滅亡,以及在995年至1025年之間促使這種觀念在京都產生的外部環境(尤其是流行病方面)中的因素。第二,本文考察天息災新譯的28品《文殊師利根本儀軌經》(T1191,約983-1000譯)是否可能為京都人所知,儘管此經當時未被入藏。此經突出了與文殊相關或者為文殊所傳授的咒語的強大轉化力量,並強調對使儀軌有效的地理區域定位。最後,本文探討了五臺山、文殊師利,以及天息災所譯《文殊師利根本儀軌經》對佛教大同世界(oikumene)觀念的貢獻。

34. ZHANG Wenliang 張文良 (Renmin University of China 中國人民大學): 古代日本人心目中的五臺山

據史書記載,第一位參訪五臺山的日本僧人是隨最澄入唐但沒有歸國、最終客死五臺山的靈仙三藏。之后入唐的圓仁(794-864)和入宋的成尋(1010-1081)都曾參訪五臺山,並在他們的游記《入唐求法巡禮行記》、《參天台五臺山記》中,留下關於當時的五臺山的珍貴記載。那麼,在平安時代和鐮倉時代的日本僧人和普通日本人的心目中五臺山是怎樣的形象呢?透過上述游記資料和其他一些史料,我們大體可以看出,五臺山在當時日本人的心目中既是一座文殊菩薩示現的道場,又是佛教學術研究的殿堂,還是通過聖跡巡禮而贖罪之地。五臺山作為中日佛教文化交流的重要場所,在日本佛教思想和佛教信仰的發展過程中曾發揮了重要作用。