On the Origins of the Great Fuxian Monastery 大福先寺 in Luoyang

Professor Antonino Forte, The Italian School of East Asian Studies, Kyoto

2:00 -4:00 pm, September 10, 2002

Buchanan B room 202

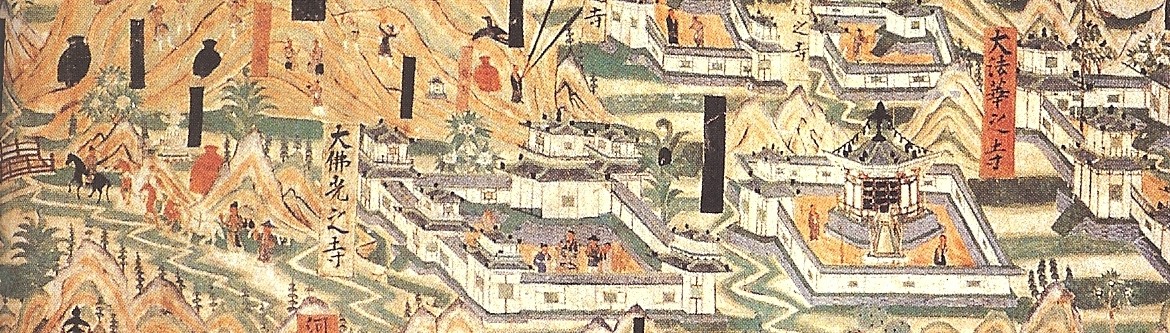

Abstract: The Great Fuxian Monastery (Da Fuxian si大福先寺) held a highly favored political and religious position in Luoyang, one of the twin capitals of the Tang and interregnum Zhou dynasties. The monastery’s early rise to significance is most intimately associated with Wu Zhao, the only woman in Chinese history to rule in her own right. Under her patronage, Da Fuxian si hosted several translation projects, overseen by eminent monks such as Divākara, Yijing, and Bodhiruci. Further, a committee headed by the monk Huaiyi—and including several eminent monks affiliated with the Da Fuxian si (Faming, Chuyi, and Huiyan)—compiled a piece of propagandist Buddhist literature justifying Wu Zhao’s rule. Yet, due in part to its relationship with the controversial female ruler, the monastery is intriguingly underrepresented in the historical records and, as a result, has yet to be fully explored in scholarship. Antonino Forte mends this oversight, providing a more complete history of the monastery by reconstructing its integral first thirty years in two parts: 1) from its establishment in 675 to the dissolution of the Tang in 690; and 2) the fifteen years of the successive Zhou dynasty, until the restoration of the Tang in 705.

PS.

This lecture by Prof. A. Forte is now being published in Studies in Chinese Religion 1.1 (2015):

To this article, Prof. Jinhua Chen, a co-edior of the journal, has added the following obituary note for Prof. Forte:

This paper is based on a lecture delivered by Antonino Forte (1940-2006) at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada in the fall of 2002 at my invitation. It was later submitted as a contribution to a volume co-edited by James Benn, Lori Meek, and James Robson. For this purpose, the article was reviewed by Lori Meek, now an associate professor at the University of Southern California. Due to his unexpected passing in the summer of 2006, Professor Forte was unable to fully revise the article in line with the suggestions provided by the reviewer. On the suggestion of Erika Forte, the paper has been presented in this publication as it was left, with only minimal edits provided by Kelly Carlton, an executive editor of this journal. Erika Forte, Norman Harry Rothschild, and I have extensively reviewed this edited version to ensure the preservation of Professor Forte’s authorial voice. Certainly, this is not the final version Professor Forte would have published if alive. Nevertheless, we thought the information might still prove useful for other scholars.

For reasons that have remained a mystery to me, Professor Forte did not visit North America until the fall of 2002, when he turned sixty-two, years after he established a worldwide reputation as a Sinologist. This occasioned my joking comparison of his visit to Vancouver with the epochal exploration into the American Continent attempted by his Italian compatriot Cristoforo Colombo (1450-1506). In retort, Professor Forte remarked, quite seriously, that while Colombo came for gold, he came for paper: an excuse to write on a cosmopolitan monastery in seventh to eighth century China closely related to the sole woman thearch—both in name and in reality—in the history of imperial China.

The female ruler he referred to is, as many readers of this journal know, Wu Zhao (624-705; reigned 690-705), the fascinating and controversial woman who intrigued Professor Forte for a substantial part of his life. Although primarily renowned for his research on the state-samgha relationship under the Great Tang and Zhou dynasties, particularly under the unprecedented reign of Wu Zhao, Professor Forte’s research extends far beyond the territory of the Tang–Zhou empire—despite the immensity of this area of research in itself. He is respected and remembered for his work on several ancient religious traditions in medieval China (such as Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism), as well as on Tang China’s multifaceted interactions with its neighboring regimes, particularly those in Central Asia.

Not merely a devoted scholar, he was also a keen promoter of international education. His work benefitted a number of younger scholars around the globe, including me. In addition to being an inspiring mentor, he is also fondly remembered as a caring friend. In the course of his long stay in Kyoto as the Director of the Italian School of East Asian Studies (ISEAS), it became a Forte family tradition of sorts to invite international students to spend the New Year’s Eve at their cozy house in Hieidaira on the outskirts of Kyoto. I am always reminded, whenever I celebrate New Year’s Eve with my family and my own students, of the scene of his student-guests lining up to accept New Year gifts (typically a sizeable loaf of panettone) that he and his wife, Lilla, “distributed” at the end of each New Year party.

Above all, Professor Forte endeavored to boldly break down boundaries he perceived might prevent the enhancement of scholarship or hinder communication among different cultures and peoples. I believe this barrier-shattering desire must have underlain his heroic effort to establish and maintain for so many years the ISEAS in Kyoto, a heaven and haven for so many international students of East Asian Studies and Buddhology working in Kyoto. It is therefore meaningful that this journal, a scholarly enterprise jointly sponsored by a leading research institution in China (the Institute of World Religions at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) and one of the foremost scholarly presses in Europe (the Routledge) includes in its inaugural issue a manuscript left by one of the greatest Sinologists of our day, a man who devoted his life to bridging the scholarly worlds in the West and East. (Jinhua Chen, on February 24, 2015, in Vancouver, Canada)