Introduction

Comic books are a form of sequential art, using a combination of illustrations and text to tell a story. These stories are influenced by the cultural concerns of the time, and change as society changes.

But this isn’t a new idea. Humans have been story telling through sequential art for 40,000 years. Paleolithic cave paintings are the first examples and can be traced back 40,000 years. Sequential art also appears in Egyptian hieroglyphics, ancient Greek and Roman structures, medieval broadsheets, and the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel (Hayman and Pratt, 2005). What separates comic books from these examples of sequential art is the addition of text. Comic books weave slang, idioms, mood, tone and connections to current cultural and political events into the story telling (“A History of the Comic Book,” n.d.).

Historical and Cultural Relevance

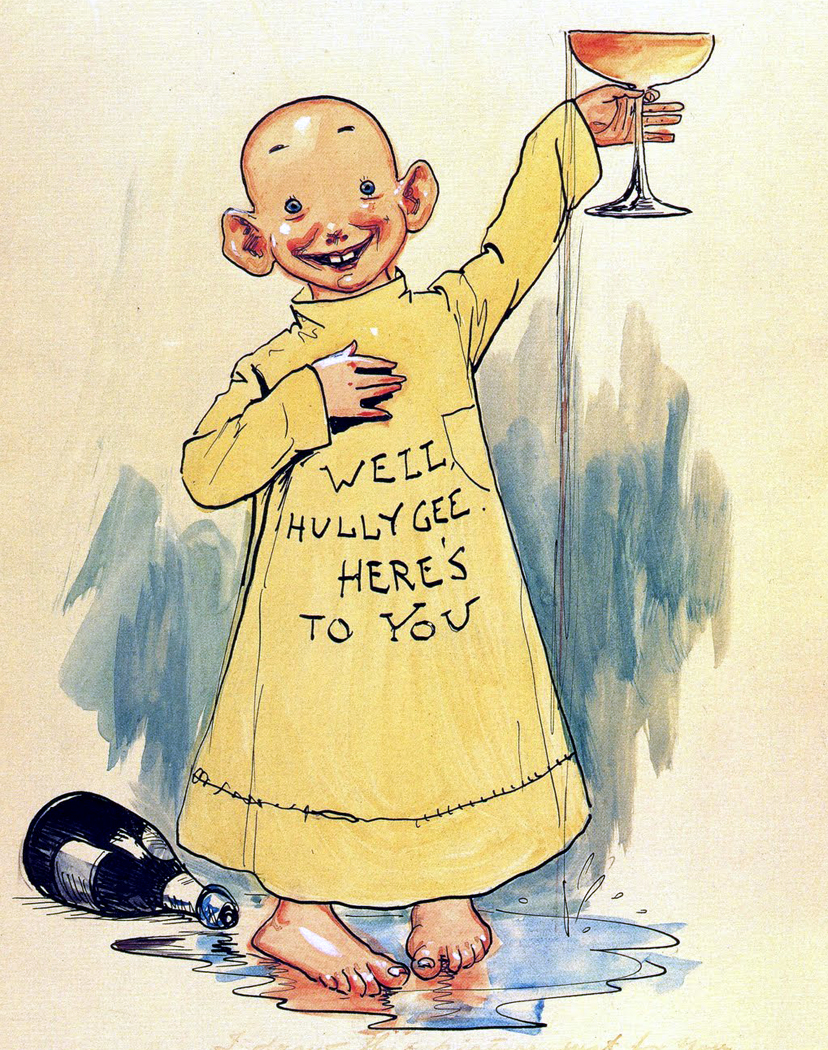

Comic books owe their existence to comic strips, which were initially produced as a means to draw readers to the Sunday newspaper in the late nineteenth century. “Yellow Kid”, created by Richard Outcault in 1895, is frequently cited as the first comic strip. It wasn’t until 1933 that Eastern Color Press found a way to utilize frequently idle printing equipment to publish an 8 page comic section, resulting in the first comic book. “Funnies on Parade” proved there was a viable market for repackaged comic strips. In 1935, National Periodicals published “New Fun Comics”, the first comic book to use entirely new content.

Comic books owe their existence to comic strips, which were initially produced as a means to draw readers to the Sunday newspaper in the late nineteenth century. “Yellow Kid”, created by Richard Outcault in 1895, is frequently cited as the first comic strip. It wasn’t until 1933 that Eastern Color Press found a way to utilize frequently idle printing equipment to publish an 8 page comic section, resulting in the first comic book. “Funnies on Parade” proved there was a viable market for repackaged comic strips. In 1935, National Periodicals published “New Fun Comics”, the first comic book to use entirely new content.

In 1938, Harry Donenfeld published Action Comics, which included the debut of Superman, the work of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. This resulted in a literary boom; superhero comic books frequently outsold major publications like Time and Newsweek. When the World War II began, comic books joined the war effort, fighting America’s villains; Captain America entered the comic book scene in March 1941, punching Adolf Hitler in the jaw (“A History of the Comic Book,” n.d.). Comic books encouraged contribution to war bonds and stamps, actively distorted views of culture and race, and celebrated racist depictions and jingoes that would not be stomached today (“TheTruth About Wartime Propaganda in Comics,” 2012).

After the war ended, superheroes ran out of authentic cultural villains to fight, and sales began to decline. Some blame this drop on censorship law and public outcry; Reader’s Digest was just one publication to release an article holding comic books responsible for the troubles facing American youth[i]. However, it can be argued that the comic book industry was more impacted by the popularity of television and rising conservative societal values. In an attempt to transform with their audience, publishers changed their tactics and true crime, westerns, and horror comic books were published.

Comic books were impacted by societal change again in the 1960s and 1970s. To meet the needs of a new generation and stay relevant, modern societal issues such as sex and drugs were featured in comic books. In the 1980s and 1990s, a national paper shortage and increased production costs led to a significant increase in comic book prices. Additionally, societal changes impacted the superheroes within, antiheroes and a darker tone and mood were introduced (“A History of the Comic Book,” n.d.).

After decades of struggling, partly at the fault of changing technology, fewer comics were selling than any other time in their history. But a connection to film and video games launched comic book characters into the forefront of mass media in the 2000s. Tabachnick (2007) describes this technological transition as a way to combine strengths, benefitting from the visual impact of the big screen while maintaining the depth and subtlety of the original text. Comic books continue to reflect societal changes caused by the events of 9/11 and modern conflicts. Most notably, a 2002 edition of Spider-Man focused on the events of 9/11 and drew a larger audience than ever before. Sommers (2012) explains this phenomenon:

Audience members around the world empathized with the character, and with each other, even more than they had when the initial events of 9/11 occurred. Spider-Man became a catalyzing agent, a shared sympathy, between disparate peoples. The totalizing effects of 9/11 collapsed the spheres of public and personal trauma into a shared experience; one not limited by national boundaries but, within its immediate time/space, a global event. (p. 190)

Tabachnick (2007) argues that serious comic books resonate with readers today because we seem to be living in a comic book world ourselves. We have seen that our world can quickly change, proving to be different than we first anticipated, quickly moving from monotonous reality to fantasy in the blink of an eye.

Connection to Literacy

Comic books remain popular today because of the strong relationship with film and media. This relationship can be connected to academic skills, not only to teach content but also to support literacy skills, communication skills, critical thinking, and motivate students beyond what other text formats are capable of (Bitz, 2004;Rapp, 2012). Students can explore literacy and find connection to their own worlds when they read and write comic books. Bitz (2004) found in his Comic Book Project that teachers and students demonstrated deeper understanding of the writing process.

The mass appeal of comic books stems from their ability to provide a space to be filled with the reader’s imagination and empathy. Hogan (2009) outlines McLuhan’s belief that comic books are a cool medium, one that provides less information to encourage audience participation. The reader can empathize with the hero, and this makes comic books the perfect tool to connect humanity and technology.

Comic book comprehension involves the active integration of both text and images. In order to understand what is being read, the reader must identify the letters and sounds that create words, understand grammar, and determine the message being conveyed. Beyond breaking down the words and sentences, the reader needs to draw inferences beyond what is stated in the text. Additionally, readers seek meaning in word balloons, narration boxes, and visual depictions. Readers learn to find the differences between comic book feature, such as what the shapes of particular word balloons means, how speed lines show motion, and how panels communicate a larger story (Rapp, 2012).

Critical thinking skills are developed through interacting with comic books, as story lines extend across multiple volumes. In order to understand these events, students must predict how the plot will advance (Rapp, 2012). Studies show that comic book reading builds literacy; children are highly motivated to read comic books, and increased voluntary free reading leads to improved reading comprehension. Comic book reading also supports English language learners as the free reading provides an opportunity for “increasing one’s competence without the risk of making errors in public” (Cho et al., 2005).

Educational Implications

Comic books are not a piece of pop culture to be overlooked by scholars and educators. Contrary to this belief, they are valuable tools that provide insight into society. In fact, they act as means to tell mature stories of great depth. “Analyzing the superhero is the perfect means of analyzing the culture. The superhero is such an asset in sociological research because the hero provides a record of the values prized by a society” (Hogan, 2009, p. 200).

Comic books are effective tools in teaching current events and history, due to their close connection with societal and cultural change. Comic books have been used to persuade Americans to support war efforts, and Aiken (2010) articulates that war efforts were also bolstered with propaganda posters, films, and news footage, and encourages the use of comic books to discuss the impact of war propaganda on society. Comic books also function as a literary link to societal issues such as poverty, racism, pollution, gender stereotypes, and political corruption (Aiken, 2010). For this reason, they can support student learning in the areas of injustice, intolerance, and social justice (Schwarz, 2010).

Aiken (2010) also describes the prolific use of media and technology in classroom as a potential distraction from learning. Despite this potential for distraction, comic books establish a common ground, which is an important element of effective teaching. Lastly, comic books can be effectively utilized to foster student’s comprehension of the classics (Rapp, 2012) and engage students in relevant social issues, while teaching “critical thinking, respect for diverse voices, empathy for fellow humans, regard for social justice, and even the incentive to work towards a different and better society” (Schwarz, 2010).

References

A History of the Comic Book. (n.d.). Random History and Word Origins for the Curious Mind. Retrieved October 19, 2012, from http://www.randomhistory.com/1-50/033comic.html

Aiken, K. (2010). Superhero History: Using Comic Books to Teach U.S. History. American Historians Magazine of History, 24(2), 41-47.

Bitz, M. (2004). The Comic Book Project: Forging Alternative Pathways to Literacy. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 47(7), 574-586.

Bitz, M. (2004). The Comic Book Project: The Lives of Urban Youth. Art Education, 57(2), 33-39.

Cho, G., Choi, H., & Krashen, S. (2005). How Comic Books Made an Impossible Situation Less Difficult. Knowledge Quest, 33(4), 32-34.

Comic Art & Graffix Gallery Virtual Museum© History of Comic Art. (n.d.). Retrieved October 19, 2012, from http://www.comic-art.com/history.htm

Hayman, G., & Pratt, H. J. (2005). What Are Comics. Aesthetics: A Reader in Philosophy of the Arts, 410-424.

Hogan, J. (2009). The Comic Book as Symbolic Environment: The Case of Iron Man. ETC.: A Review of General Semantics, 66(2), 199-214.

McCloud, S. (1993). In Understanding comics: The invisible art. Northampton, MA: Kitchen Sink Press.

Rapp, D. (2011). Comic books’ latest plot twist: Enhancing literacy instruction. Phi Delta Kappan, 93(4), 64-67.

Schwarz, G. (2010). Graphic Novels, New Literacies, and Good Old Social Justice. The Alan Review, 37(3), 71-75.

Sommers, J. M. (2012). The Traumatic Revision of Marvel’s Spider-Man: From 1960s Dime-Store Comic Book to Post-9/11 Moody Motion Picture Franchise. Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, 37(2), 188-209.

Tabachnick, S. (2007). A Comic-Book World. World Literature Today, 81(2), 24-28.

The Truth About Wartime Propaganda in Comics | inspirationfeed.com. (2012, February 24). Inspirationfeed – be inspired!. Retrieved October 20, 2012, from http://inspirationfeed.com/articles/design-articles/the-truth-about-wartime-propaganda-in-comics/

[i] Reader’s Digest published several articles describing the negative impact of comic books on child behavior. Fredric Wertham’s “The Comics . . . Very funny!” in August 1948 and “Comic Books – Blueprints for Delinquency!” in May 1954, and T.E. Murphy’s “The Face of Violence” in November 1954. They were not the only publications to focus on anti-comic book arguments; others include Parent’s Magazine, Family Circle, Newsweek, and The New Yorker.

Kym, interesting to be reading your paper at this point in the course while reading Bolter (2001), Kress (2005), and Hayles (2003) with respect to the visual and images overtaking the written word as a means of conveying information to the reader or “viewer”.

I would love to know more about how the first insert of comics came about. Did the advent of colour print in newspaper have anything to do with the idea?

Sorry for my late reply, I just figured out today how to find my replies. I didn’t actually find a connection between the advent of colour printing and evolution of comics. Comics have a strong connection with war efforts, as well as with newspaper sales. Comic creators were trying to repurpose their Sunday funnies into colour publications in order to make a little moolah and gain a broader audience. I often wonder if they had any idea where these little books would be in 70+ years!

As a boy who grew up with comics, I would say that it brings a smile to my face to see more and more comic book (graphic novel) sections in school libraries lately. They were considered uneducational trash when I was in school, banned media. Today, most teachers would hopefully support the idea that the more variety of text mediums that students are exposed to the better. That idea in addition to the way you describe the multiple skills that are exercised during comic book reading and the meaningful way it can display content, makes comics sound pretty valuable to education. Plus they read pretty well on an iPad.

I still worry that there is a bias attached to the reading of comics and graphic novels. Often they are encouraged for struggling readers, as a means to dumb-down literature. There is so much to offer within the graphic novel, that we need to be considering them to motivate all students, regardless of their reading abilities. What we read between the gutters and panels of a graphic novel is like what we infer when we are watching film – how we can get to know a character by what they look like, how they treat others, how others treat them…not just what they say and do. There is so much depth to visual literacy. Thanks for your comments!