Tara Avenia

(Avenia, 2012).

[youtube]http://youtu.be/_XngtsmH9FU[/youtube]

(Avenia, 2012)

“Among the Greatest Benefactors of Mankind”

A close look into the history of educational technology will reveal that an invention from over two hundred years ago remains arguably the most influential technological innovation of our time. It was Josiah F. Bumstead who first declared in his 1841 essay, The Blackboard in the Primary Schools, that the chalkboard is a groundbreaking technological invention (Krause, 2000). Numerous scholars have agreed with Bumstead’s pronouncement citing in reference to the chalkboard that “the inventor or introducer of the system deserves to be ranked among the best contributors to learning and science, if not among the greatest benefactors of mankind” (Krause, 2000, p.11; Ressler, 2004, p.71; Tyack & Cuban, 1995, p.121). With the advent of compulsory schooling in the United Kingdom in the late eighteen hundreds and the significant increase in student population in public schools, the British acknowledged a sudden need to adopt a unified education program. The chalkboard stood at the core of this new teaching culture. This report will argue that the chalkboard gave rise to the standardization of public education, and its integration into English classrooms in the nineteenth century led to the widespread advancement of rote memorization as the dominant teaching pedagogy in the United Kingdom.

The Invention of the Chalkboard

The chalkboard is widely believed to have been invented by a Scottish teacher James Pillans, in the nineteenth-century (About Blackboards, para. 7). Mr. Pillans “supposedly hung his students’ slates together on the wall, making a large ‘slate board’ to write up his geography lessons where the whole class could see them at once” (Wylie, 2012, pp. 259-260). The first documented case of the chalkboard however is found in America in 1801. Mr. George Baron is credited as being the first teacher to make use of a large black chalkboard to assist him with his instruction at West Point Military Academy (About Blackboards, para. 8). Regardless of where it was invented, either in the United Kingdom or in the United States of America, the fact remains that the chalkboard was created by teachers to assist with teaching, and is an important educational technology.

A Necessary Educational Technology

The Council on Education in England officially recognized the chalkboard as a classroom necessity in 1844. Wylie (2012) contends that this permitted the use of state funds to go toward purchasing the educational technology for the first time in history. Surprisingly, it took nearly thirty years to pass the 1870 Education Act that provided universal elementary education to all British children (“Key Dates in Education,” n.d.). As Krause (2000) contends, “from almost the beginning, the chalkboard seems to have been a technology that was universally accepted, immediately adopted, and widely praised” (p.11). History demonstrates that the chalkboard was adopted before universal education. This is partly because the chalkboard is an economic educational technology. Krause (2000) declares that chalkboards “are easy to operate devices that are cheap, low-maintenance, and long-lasting. They are simple to use, flexible in application, and extremely reliable” (p.12). Tyack and Cuban (1995) make reference to a chalkboard salesman from 1841 who describes the chalkboard as “the MIRROR reflecting the workings, character and quality of the individual mind” (p. 121). Many would agree with Krause’s proclamation that the chalkboard “was and remains an ingenious teaching tool and a significant contribution to the ‘technology’ of the classroom” (p.12).

The Standardization of English Education

The increase in student population that resulted from the 1870 Education Act in Britain created the need to standardize education. Krause (2000) proposes that the British are responsible for the Lancasterian method that was arguably “one of the first ‘systematic’ approaches to education” (p.10). This newly standardized approach was advertised throughout the country via teaching manuals, which were published in mass and as Wylie (2012) contends “promote pedagogy as largely universal” (p.261). The chalkboard, having been deemed a necessity, was aggressively promoted in these teaching manuals that spread the word of this new standardized approach to education. Krause declares “chalkboards … were an essential part of the Lancasterian method because [they] kept costs low by minimizing the use of paper, ink, pens and books, and because [they] facilitated group instruction by monitors and teachers” (p.10). A closer look at two teaching manuals published in the late nineteenth century demonstrate that the chalkboard, also called the blackboard, was the “main-stay and sheet anchor of a lesson” (Livesey, 1881, p. 6). In How to Prepare Notes of Lessons: A Manual for Pupil Teachers and Students in Training Colleges, Taylor praises the chalkboard for its invaluable impact on teaching and learning. Taylor writes that:

The blackboard is always at hand, and blackboard drawing has advantages peculiar of itself. The teacher can draw to any suitable scale – he can construct his drawing before the class – he can simplify it by divesting it of all un-essentials, he can produce it at the moment, and in a manner calculated to insure close attention. We would earnestly encourage all young teachers to cultivate assiduously the art of blackboard drawing. (1881, p. 29)

With the advent of universal primary education, and the acquired need to standardize the British education system, teaching manuals were published and distributed throughout the country to communicate the pedagogical change. The manuals were meant for teachers, they communicated the correct method to teach and to learn and always promoted very specifically how to use the chalkboard to achieve these means.

Rote Memorization Becomes The Dominant Teaching Pedagogy

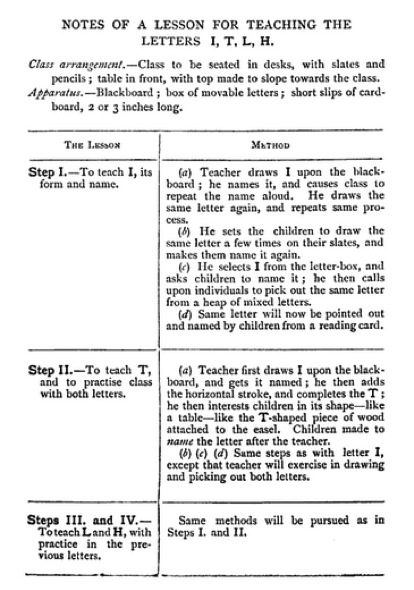

Teaching manuals produced in the late nineteenth century in England outlined in precise detail how a lesson was to be taught. Wylie (2012) concurs that the “instructions portray the teacher as explainer, demonstrator and corrector. There is no active knowledge construction by students, only explanation followed by drill, with the teacher giving corrections” (p.261). The emphasis on rote memorization is demonstrated below in figure 1. In this lesson, Taylor (1881) demonstrates to the teacher the step-by-step process to teach the letters I, T, L and H. He leaves little to the imagination of the classroom teacher.

Figure 1 (Taylor, 1881, p.34).

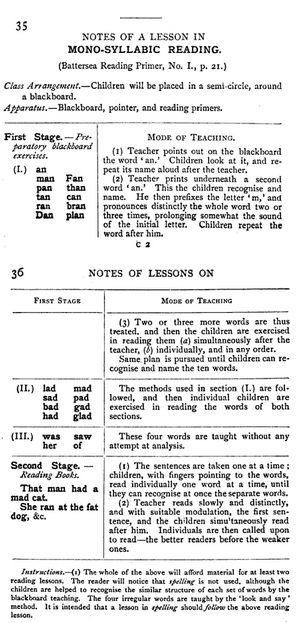

The teaching manuals produced in the late nineteenth century included chalkboard instructions for every subject; some surprising examples include lessons on sound, listening to music, and on the topic of healthy exercise (Livesey, 1881). These are lessons that would arguably be better taught through action, in a student-centered approach. Livesey (1881) emphasizes this in his teaching manual, Moffatt’s How to Prepare Notes on Lessons; he states that a science lesson should be about discovery, and should be student-centered. Livesey goes on however to outline the exact script a teacher should say when teaching science as well as listing precisely what the teacher should write on the blackboard and when (pp. 22-25). Figure 2 is an example of a lesson from 1881 that instructs the teacher in a step-by-step fashion how to teach their students to read. As Wylie (2012) points out, “even reading, a deductive decoding skill that is rather different from memorising how to write letters, was taught through imitation and drill, with the blackboard as a demonstration space” (p.262). Take notice of the lesson prefix that includes instructions on classroom setup.

Figure 2 (Taylor, 1881, pp.35 – 36).

Wylie (2012) contests that “the end goal of these [teaching] methods was memorisation, achieved through students’ repetition of corrected, acceptable imitation of the teacher’s model” (p.264). The teaching manuals produced in the late eighteen hundreds taught a teacher to teach much like you teach a very young child to paint, by numbers. Wylie (2012) contests that these “manuals on traditional subjects are written as commands and specific instructions …[and] thus teachers were meant to learn through imitation, just like their students” (p.270).

The Future of the Chalkboard

The blackboard is an adaptable technology and extremely reliable. As Puryear (1999) defends, the chalkboard is inexpensive to produce, easily distributed, and portable. The chalkboard is easily mastered by anyone with basic literacy skills, so although it was introduced with the teacher centered rote memorization pedagogy at its core, it could just as easily be used to enhance education placing students in the center. Ressler (2004) contests that the chalkboard is a fundamental tool to facilitate learning because “the learning process is about making connections” (p.71) and a chalkboard permits the text to remain visible for the students. Ong (1982) may argue that because text on a chalkboard is permanent in a way that electronic text is not, a student who learns from a chalkboard is better suited to recall the text at a later date. Both Ong and Ressler would agree that “a chalkboard – especially a large one- facilitates the creation of such connections by allowing students to view, discuss, and process several related topics simultaneously” (Ressler, 2004, p.71). Perhaps the chalkboard, and its twentieth century cousin, the digital whiteboard, will remain an educational technology for another two hundred years. In time, I predict, those who use the chalkboard to teach will learn to do so in a constructivist manner, moving further away from the rote memorization pedagogy of our past.

References

About blackboards – blackboard technology and chalkboard history advances. (2012). In Ergo In Demand online. Retrieved from http://www.ergoindemand.com/about_chalkboards.htm

Avenia, T. (Artist). (2012). Chalkboard Presentation Title Card [Image file].

Avenia, T. (Artist). (2012). Chalkboard Word Art [Image file].

Avenia, T. (Producer). (2012, October 28). The history and future of the chalkboard [Video]. Video retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_XngtsmH9FU&feature=plcp

Chalk stick write on chalkboard [Audio Sound Effect]. (n.d.). In freeSFX online. Retrieved from http://www.freesfx.co.uk/sfx/chalk

Key dates in education: Great Britain 1000-1899. (n.d.). In Educational Resources online. Retrieved from http://www.thepotteries.org/dates/education.htm

Krause, D. A. (2000). “Among the greatest benefactors of mankind”: What the success of the chalkboard tells us about the future of computers in the classroom. The Journal of Midwest Modern Language Association: Computers and the Future of the Humanities, 33(2), 6-16. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1315198

Livesey, T. J. (1881). Moffatt’s How To Prepare Notes on Lessons [Digitized by Google]. London: Maffat & Paige. Retrieved from https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=iCACAAAAQAAJ&hl=en

Ong, J. W. (1982). Orality and literacy: The Technologizing Of The Word. London: Methuen.

Puryear, J. M. (1999, September). The economics of educational technology. Tech KnowLogia, 46-49. Retrieved from http://www.techknowlogia.com/TKL_Articles/PDF/17.pdf

Ressler, S. J. (2004). Whither the chalkboard? Case for a low-tech tool in a high-tech world, Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Practice, 130(2), 71-73. doi: 10.1061(ASCE)1052-3928(2004)130:2(71)

Taylor, W. (1881). How To Prepare Notes Of Lessons: A Manual For Pupil Teachers And Students In Training Colleges [Digitized by Google]. Westminster: National Society’s Depository. Retrieved from https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=uSECAAAAQAAJ&hl=en

Tyack, D., & Cuban, L. (1995). Tinkering Towards Utopia: A Century Of Public School Reform. The United States of America: Harvard University Press.

Wylie, C. D. (2012). Teaching manuals and the blackboard: accessing historical classroom practices. History of Education: Journal of the History of Education Society, 41(2), 257-272. doi: 10.1080/0046760X.2011.584573

Nothing in my mind is more closely associated with wrote learning than the chalkboard.

I agree, but I honestly believe that it doesn’t have to be this way. Just because it was taught to teachers in this fashion, and because teachers then taught their students to memorize information in the same way, doesn’t make it right.

Ressler argues that the chalkboard is a tool to facilitate twenty-first century teaching, with a student-centred approach. He suggests that because the text remains in the students view for the entire lesson, the students can draw connections between the content. He reminds his readers that these connections is what teaching is about. 🙂

I know the chalkboard has a bad rap…as someone in the class mentioned…”all that dust and a tool that becomes useless when wet” but still I love the idea of a chalkboard. When you see kids using it to create when they are small and even adult learners can benefit as you say, from having the words or images visually available for reference throughout the duration of the class – this is useful. I could live without the dust but I’d still use a chalkboard when the learning afforded it. (-:

Great job on the intro too. Did you use prezi?

I did use prezi for the introduction. Thanks for the positive feedback.