Interviews are a series of questions and answers and as social scientists we presume both use words. More common in the arts community is the possibility answers can be entirely or partly in the form of drawings, illustrations, images. Thinking about illustrated interviews within social science opens possibilities in forms of thinking and representation that often go untapped in interviews.

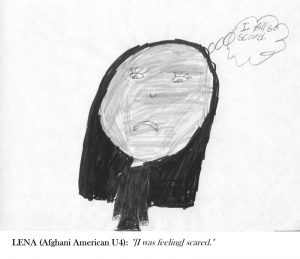

Asking interviewees to draw pictures that become part of interviews is a strategy I have used with children. Studying the impact of high stakes testing on children, I asked them to draw a self-portrait whilst taking the test. They also wrote a caption for the self-portrait and these drawings were used to engage the children in an interview about their experience.

In this same study, children kept journals and were encouraged to write and draw. Not every child drew but most did at least some of the time suggesting the flexibility to chose how they represented their experience enhanced the likelihood of authentic sharing. You can read a report of this research here.

The NYT does a series of illustrated interviews… asking simple questions and having celebrities draw responses, which are then modestly animated resulting in a sense of action. Some interviewees are skilled at drawing, many are not. The interviews share a common set of questions and thus reveal a “life” for each person.

There are examples of drawings that represent concepts or ideas, like Jennifer Burtchen’s drawings of time, her drawing of the “present” shown here. This is one of a series of illustrated interviews in the magazine Ignant.

There are examples of drawings that represent concepts or ideas, like Jennifer Burtchen’s drawings of time, her drawing of the “present” shown here. This is one of a series of illustrated interviews in the magazine Ignant.

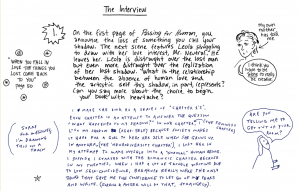

Liana Finck and Amy Kurzweil are both cartoonists and in this interview about a book written by Finck they use drawings in the margins of a more typical Q & A format to amplify the written responses.

Incorporating illustrations in interviews can be done in a number of ways:

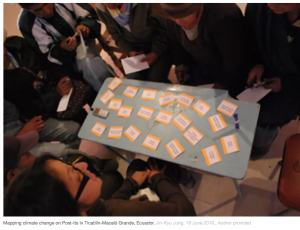

- interviewees respond in drawings, sketches, or even photographs

- interviewees generate drawings that are used during an interview

- interviewer drawings are used to enhance, elaborate, accompany questions

There are many examples of using drawings when doing research with children, but this strategy can work with adults as well.

Follow

Follow