Representing Nature in an Illustrated Khamseh of Nezami Manuscript by Yasaman Lotfizadeh

Interpretations of equity: Nature, spirituality and stories of companionship

On her way to completing a Masters in Interdisciplinary Graduate Studies, Yasaman Lotfizadeh weaves art history, environmental humanities and digital humanities to look back in time at illustrations of a Persian book of poetry from five hundred years ago. This research draws attention to often overlooked Persian illustrated manuscripts that are rich depictions of nature in art. They also highlight inequities of representation, for example, the underrepresentation of women and power negotiation between humans and the natural world. Read an excerpt of this scholarship and two stories from the illustrated Khamseh of Nezami manuscript.

About the research

My research seeks to understand how Islamic art is adjusting to the digital turn. Art history, environmental humanities and the digital humanities generally pay little attention to the arts of the Islamic world. Art history scholars are now using computational and digital tools to analyze historical subjects and with the increase in these tools’ development, reflecting on their limitations is also critical.

This work recognizes and uncovers less studied Persian illustrated manuscripts yet to be acknowledged in digital humanities scholarship. The usefulness of digital humanities tools and theories in studying Islamic and Persian paintings’ text-image relationships is still limited, although there are researchers who have recently attempted to do so. In Iran, where Persian illustrated manuscripts were produced, they might be overseen or neglected in detail, particularly in relation to new technologies. This suggests why Western scholars have conducted the main corpus of Islamic and Persian art scholarship, while some studies done elsewhere remain old-fashioned. It also further sheds light on how women are underrepresented in the scholarship of Islamic art, particularly in Iran but not necessarily in Euro-American scholarship. Islamic and particularly, Persian art history continues to be articulated by either Western scholars or those trained in the West. The emergence of digital humanities tools and theories in Islamic arts is even less applied in the scholarship around Persian paintings. Therefore, one of my study’s critical contributions is setting the ground for more such scholarship to look at previously studied material through the new lens of digital humanities tools and theories. Although I have highlighted text-image close-looking in my case study, what I have brought to the surface is a great need to further investigate the usefulness of digital humanities tools and theories.

About the illustrated Khamseh of Nezami manuscript and visualization techniques

Around 500 years ago, a Persian Safavid art-lover king, Shah Tahmasp, commissioned an illustration of a well-known Persian poetry book, Khamseh, by poet Nezami Ganjavi. Hundreds of illustrated copies of this poetry book survive today in collections worldwide. Among them, the Or. 2265 illustrated manuscript is the focus of the current study, which now belongs to the British Library collection, and has been professionally digitized. With a different approach and the help of digital tools, and close-looking methods, I studied the relationship between this manuscript’s illustrations and their corresponding text with a particular focus on the natural world and the ideas that could have influenced painters’ choices of visual elements. For my Masters, I focused on three Khamseh compositions among five, including Makhzan al-Asrar, Khosrow o Shirin and Leyli o Majnoon. Owing in part to the accessibility of Or. 2265’s high-quality illustrations through the British Library website collection, its complex history and the large corpus of scholarship on the manuscript encouraged me to look at it through different disciplinary lenses and in an interdisciplinary way.

I employed digital tools to produce visualizations, and a close-looking methodology, to add to the traditional methods. This approach aided me in developing meaningful relationships and deepening my understanding of text and image relations. I employed data visualizations to better investigate how text and image were and were not related. By capturing more detail across text and image, data visualizations add to the traditional methods. The availability of sophisticated digital tools allows researchers and practitioners alike to explore visual art in new ways. These tools increase the speed and depth of analysis and bring to the foreground the minutia of details that would otherwise be difficult to discern.

The study concluded that along with the importance of the painter’s power over the depicted nature, the philosophy and ideological beliefs of the poet and the illustrator helped form the representations of the natural world in BL Or. 2265. Therefore, people’s relation with the elements of nature is strongly shaped not only by ideas about power and pleasure but by spirituality too.

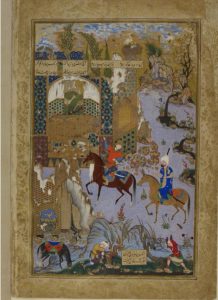

Story: “Nushirvan and the Owls” and Folio 15v

http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=or_2265_f015v

In Makhzan al-Asrar’s Nushirvan and the Owls (f 15v) (See digital version of Folio 15v), Nezami tells of a king’s reckoning with his oppressive policies through two talking birds who are in conversation with one another. Noticing their sound, Nushirvan asks his vasir (minister) about the subject of their discussion. Worried about how the king would react, the vazir explains that these birds, one a groom and the other the groom’s future father-in-law, are talking about an upcoming wedding and discussing the bride’s dowry. The groom demands one or two ruined villages, and the bride’s father answers that if the king continues to rule as he is ruling, all his subjects would soon be in misery and that he can give the groom not one or two ruined villages but hundreds.

Through assigning verbal and decision-making abilities, in “Nushirvan and the Owls,” the two wise owls are considered equals to humans. As the story suggests, the owls’ conversation guided the king to the right path, and he became a just king afterwards. The story suggests that as readers of Nezami’s words, we are not concerned about animals themselves, rather, they are the allegorical source and vehicle of wisdom.

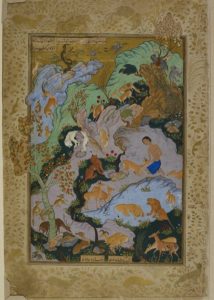

Story: “Majnoon with the Animals in the Desert” and Folio 166r

http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=or_2265_f166r

The story of “Majnoon with the Animals in the Desert” from Khamseh’s third composition, Leyli o Majnoon, is depicted in f.166r (See digital version of Folio 166r). In the Leyli o Majnoon composition, the young Qays and Leyli initially fall in love at school. Following his unsuccessful marriage proposal, Qays becomes mad, that is majnoon, and subsequently leaves his family and clan. A major event in the story of Leyli o Majnoon is the death of Majnoon’s father. Following his father’s death and his encounter with Leyli, Majnoon joins his empathetic wild animal companions, a group of predators and prey who peacefully coexisted in the desert. When living in the desert, wild beasts rank to become Majnoon’s companion, as well as a gazelle with whom Majnoon kneeled on the ground in f.166r.

In this folio and its corresponding text, the natural world is described as an intermediary through which human beings can seek selflessness and reach the source of beauty: God. Here, both poet and painter suggest human and animals living in harmony and avoidance of violence.

Outside mysticism, humans think they need to tame the one they love, which creates inequality, and mysticism is against that. Taming someone is taking control of or exercising power over another. Similarly, nature is tamed in a garden, and therefore it is not an appropriate setting for Nezami’s story of Majnoon, which is widely about selflessness and becoming care-free. This makes perfect sense for Nezami to place the story of f.166r (Majnoon in the wilderness) in the wilderness where nature is pure and untamed to which mysticism urges. The notion of equality, which is a reflection of mysticism and morality, is also reflected not in the story’s text, but in the mentioned painting, where both Majnoon and the gazelle are depicted equally on their knees.

Concluding thoughts

My study advances the argument that through close-looking and application of data visualization tools, four fundamental ideas– pleasure, power, spirituality, and people — proved to have influenced painters’ decisions when depicting selected stories of Khamseh.

As the scholarship around Persian illustrated manuscripts is relatively small, this research will push the boundaries and bring to the fore new insights that are not easy to observe otherwise. Although my focus has been looking closely at the natural world in one illustrated manuscript from a digital humanities perspective, there is the possibility of larger ideas about providing awareness for humankind to make sense of today’s natural world issues by looking at how nature used to be presented, regarded and treated.

Persian illustrated manuscripts are globally admired by Persian arts enthusiasts and have been extensively studied in academia. However, the language and culture of these works may be beyond the knowledge and competency of the viewer. Non-Persians may also face challenges when looking at these works of art, as texts and images are sometimes culturally coded. Despite many Persian historiographical studies, much remains to be done in a detailed analysis of the cultural context of the ‘Persian arts of the book’ as one Islamic arts branch. Through this study and similar ones, observations can generate a new visual culture of the selected historical period, promote social development and help preserve cultural material through knowledge creation.

Reference

Niẓāmī Ganjavī. (1539-1543 ). The ‘Khamsah’ of Niẓāmī (Digitized manuscript). https://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Or_2265