If the problem that André Malraux’s Days of Hope poses is that of the confrontation between the virtues and emotions of human subjectivity–hope, courage, enthusiasm–and a new form of mechanized warfare that puts a premium on objective technological efficiency, this is complicated by the fact that the very opposition repeatedly breaks down. For on the one hand the machines cannot be so easily reduced to an instrumentalized, technical logic. And on the other hand, the figure of the human is constantly in danger of disappearing or of being subsumed into a more general and impersonal landscape of affect. In short, the machines seem to take on a life of their own, while the men (and women) fighting the war have trouble holding on to their appearance of individualized identity.

Some of this blurring of the machinic and the human is a matter of perspective. After all, Malraux shows us the war from the air, a point of view that might be imagined to offer a broader and more objective panorama, but which in practice simply confounds established certainties. Hence when the Republican Flight brings along a local peasant, to help them locate a hidden Falangist airstrip, at first his local knowledge of the terrain proves useless, as he is unaccustomed to looking down on it from above: “His mouth half-open, and tears zig-zagging down his cheeks, one after the other, the peasant was straining every nerve to see where they were. He could recognize nothing” (395). But more broadly, even for seasoned pilots, from the air things take on a different aspect. On one of their early mission, for instance, they see a road “studded with little red dots. [. . .] too small to be cars, yet moving too mechanically to be men. It looked as if the roadway itself was in motion.” This turns out to be a column of Fascist lorries, but to see them as such requires the pilot to have “a gift of second sight: seeing things in his mind, not through his eyes.” And even then, he retains the impression that the landscape and infrastructure itself has come to life as he observes a “road [. . .] that throbbed and thundered–the road of fascism” (86).

But even closer to the ground, the distinction between the animate and the inert is often hard to discern. At one point, for example, during the defence of Madrid, we are provided with the perspective of a fire-fighter named Mercery high up on his ladder, who imagines himself battling “an enemy with more life in it than any man, more life than anything else in the world. Combating this enemy of a myriad writhing tentacles, like a fantastic octopus, Mercery felt himself terrible inert, as though made of lead” (342). Shortly thereafter, machine-gunned by a Fascist plane, he is described as “living or dead” as he “still clung to the nozzle of his hose”–as though the border between life and death had here become strictly undecidable, or perhaps (however briefly) irrelevant. Elsewhere, even the confrontation between infantry and tank, which is otherwise staged as the classic clash between man and machine (for faced with the tank only the dynamite-laden “dinamiteros [. . .] can face the machine on equal terms” [197]), is also put into question. At Guadarrama we discover that “a machine can seem startled on occasion.” Faced with anti-tank machine guns, “four of them–three in the first line, one in the second–tilted up simultaneously with an air of puzzlement: ‘What on earth is happening to us now?’” (310).

And at the Battle of Teruel, things are further complicated by the deployment of a loud-speaker, a machine that talks: “inert, yet alive because it spoke” (381). Later, as the noise of battle dies down, it is described in personifying terms: “the loud-speaker had been waiting for this lull” (384). More generally, the technology of mass reproduction–represented here by cartoon characters such as “Mickey Mouse, Felix the Cat, Donald Duck” (368)–conjure up “the modern fairyland, the world in which those who are killed all come back to life” (369). Technology both brings to humanity death and destruction but also offers the world forms of (re)animation that trouble the very distinction between human and inhuman, living and dead.

If then the machines increasingly take on a life of their own, what distinguishes the human? At the best in the novel, the men and women who populate it eke out a fairly shadowy and precarious existence. Again, this is partly a function of the recurring aerial perspective: from on high or far off, people either disappear are easily dehumanized, for instance (in the case of deserters going over to the enemy) appearing to be no more than “insects waving their antennae” (305) or (in the case of Fascists flushed out of the forest) adopting “the same panic-stricken scamper as the herd of cattle they had just stampeded” (398). Again, however, even on the ground they tend to dissolve into the environment: “shadows,” “ghosts,” “wraiths,” and “shadowy forms” in the Madrid mist, for example (265, 266, 267, 270); or collectively constituting “a frenzied mass” (204) or a “panic-stricken mob [. . .] like leaves whirled together and then dispersed by the wind” (225). Even in terms of the novel’s own representational strategy, which constantly jumps between locations and discrete episodes, there is little attempt to give many of the characters much realist depth or rounded individuality; they tend simply to incarnate particular positions or singular attitudes, becoming spokespeople for (say) Anarchism or Communism, or exemplary instantiations of stubbornness or self-sacrifice.

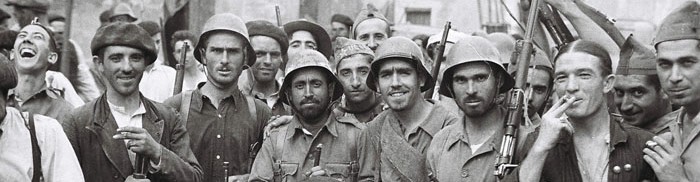

If there is something that, for Malraux, can (still) be said to be distinctly human, it is perhaps the face. This perhaps is why the novel repeatedly recurs to the human face, and to the notion that the face somehow stands in for individual character (men are variously described, for instance, in terms of a “jovial solid-looking jowl” [9] or a “predatory face, hook nose, and twinkling eyes” [18] and so on), and also more generally for shared humanity. In an atmosphere frequently characterized by gloom and indiscernibility, Malraux often has faces suddenly revealed or lit up, as for instance when an explosion at Toledo catches a group of dinamiteros “open mouthed, their cheeks lit by the livid purplish sheen of flame and moonlight mingled [such that] each saw the face that he would wear in death” (199). Or when an aeroplane is caught in a searchlight and “a sense of comradeship in arms pervaded the cabin flooded with menacing light; now for the first time since they began the flight, these men could see each other” (234; emphasis in original) and as a result, in the aftermath, each of the crew “had vividly before him the picture of the features of his comrade as they had been thrown into relief for that brief moment” (235). There is something about the face of the other that gives us both his (or her) truth, and reminds us of some shared commonality.

Except, of course, that warfare also destroys the face and our perception of it. On the one hand, the novel repeatedly gives us instances of blindness, either permanent or temporary, which make it impossible to see the face. And the face of the blind is also somehow grotesque, we are told: the father of the blinded airman Jaime tells us that he “can’t bear to look at his face” (279). But war also mutilates its victims such that there is no face to be seen. This is what happens to Gardet, another airman, whose plane crashes towards the end of the book: his face is “slashed wide open from ear to ear. The lower part of the nose was hanging down.” As a result, would-be rescuers flee from the sight, and Gardet muses “If I look at my mug just now, I’ll kill myself” (409). Even bandaged up, the effect is that of “a tragic bas-relief of Armageddon” (411).

Throughout, then, Malraux tries to maintain the distinction between human and machine (as well as between the human and he animal), but ultimately the war puts such differences into question. More likely, we end up with a variety of hybrid combinations of man, machine, and nature, in which what is presumptively object is animated and gains features of subjectivity (such as affect and agency), while men and women defer or abdicate some part of their subjectivity as they take up their places in the “endless flux of things” (423). Sometimes these hybrids are empowering, as with the case of the pilot who “feel[s] the contact of the stick, welded to the body, identified with it” (401). Sometimes they are grotesque, as with the battering ram used at the siege of the Montaña Barracks, a “strange geometrical monster” (32) wielded by men on either side of it, one of whom dies under fire and “slump[s] across the moving beam, arms dangling on one side, legs on the other. Few of his companions noticed him; the battering-ram continued lumbering slowly forward, with the dead body riding it” (33). Here, man and machine, animate and inanimate, dead and alive all come to constitute a collective apparatus of war in which any categorical distinctions are untenable if not irrelevant. This complicates any notions of fraternity. Yet such is modern warfare. And in so far as war teaches us how to live (Manuel, perhaps the novel’s major character, tells us that “a new life started for me with the war” [428]), it is also, quite simply, modern life.

See also: Days of Hope I; Spanish Civil War novels.