Welcome to UBC Blogs. This is your first post. Edit or delete it, then start blogging!

Hello world!

Welcome to UBC Blogs. This is your first post. Edit or delete it, then start blogging!

San Camilo, 1936

San Camilo, 1936 II

There are radios throughout Camilo José Cela’s San Camilo, 1936. One of the major characters, the ardent Republican Engracia, even has a boyfriend who repairs radios. But they often go unheard. At the crucial moment at which the news comes through that a “part of the army in Morocco has risen in armed rebellion” (152) it seems that nobody is listening. We are told of the maids Paulina and Javiera, for instance, that they “always have the radio on, but turn it off whenever the news begins, it’s so boring” (153). When more information starts to come through of events in North Africa and the Canaries–and at the novel’s first mention of Franco–it’s said that “few people listen to the radio, and fewer still at eight o’clock in the morning, at that time hardly anyone thinks of listening to the radio [. . .] you really have to be a morning person and the inhabitants of Madrid tend not to be morning people, it’s not worth it” (157). So it takes some time to register what is going on.

In fact, even by the end of the novel (almost two hundred pages later), it is hardly clear that many, if anyone, have really registered that an epochal change has taken place, a historical rupture opened up. The first mention of the phrase “civil war” comes a good fifty pages after what, with hindsight, would become known as its outbreak, and even then it is presented as a future possibility that might yet be averted if the army would only “bring peace and prevent all these events from degenerating” (213). But there is some vacillation here: if peace still has to be brought, does this not imply that war has already broken out? Amid all the uncertainty on which Cela’s novel thrives, the very border between peace and war becomes diffuse, undecidable. In the book’s epilogue the narrator’s uncle, Jerónimo, declares that “we Spaniards live in a start of permanent civil wars, in the plural, all against all, but also in an inhospitable civil war against ourselves and with our wounded and suffering hearts and battlefields” (358). But this sounds more than anything like a Hobbesian state of nature, as if the problem were that there is no Spanish “civil society” at all, no nation over which contending sides could fight.

And indeed, Uncle Jerónimo comes out against the nation, but in favour of the patria or fatherland: “the fatherland is more permanent than the nation, and more natural and flexible, fatherlands were invented by the Great Creator, nations are made by men, fatherlands have a language with which to sing and trees and rivers, nations have a language that’s for promulgating decrees” (357). In short, in Jerónimo’s hands–and the epilogue is given over almost entirely to his voice alone, in contrast to the multiplicity of voices and perspectives that characterize the book until that point–the novel shifts from what I early called infrapolitics to an avowed antipolitics whose (in fact, merely disavowed) political investments are clear enough. For Jerónimo is less opposed to politics than he is to the liberal institutions of the nation state that he–like Franco–is quite prepared to sacrifice for the greater good of a notional “fatherland” whose purported legitimacy and authority are given by God himself. Hence also the novel’s rather chilling final lines, declaring that “whatever you think this is not the end of the world, [. . .] this is but a purge of the world, a preventative and bloody purge but not an apocalyptic one [. . .] we can calmly go sleep, it must be very late already, I assure you that suffering is less important than how you conduct yourself, let’s go sleep, it must be very late already and the heart gets weary with so much foolishness” (366). All is well, please move along, nothing to see here, just a little housecleaning and the fatherland will rise again.

There is a logic to this conclusion, if we take what has gone before, with Madrid portrayed as a hotbed of licentiousness and prostitution, as a sign that the stables now need to be cleaned out and the corruption of politics erased. This is more or less the argument of Paul Ilie who, in a remarkably angry article (I have seldom seen one angrier) on “The Politics of Obscenity in San Camilo, 1936”, claims that Cela goes out of his way to portray the Republic as obscene so as to justify the (eminently political) rejection of politics. At the same time, Imre points out, Cela wants to have his cake and eat it: what he provides is “political pornography” that “seeks to titillate bourgeois taste by means of verbal prurience, immoral suggestiveness, and sado-erotic anecdote” (51, 47).

But instead of dwelling on the all-too familiar hypocrisy of this rhetorical tactic, another way of reading the novel would be to emphasize the ways in which the final epilogue doesn’t so much follow on from what has gone before as attempt to capture it, ultimately without success. For something always escapes–and here, that something is plenty. To put this another way: the epilogue is a betrayal of everything that makes the rest of the novel so fascinating and worthwhile, even if it is a betrayal that has been building from the start, long planned from the very moment at which Cela gives us his narrator staring at the mirror, idly masturbating, wondering whether to sleep with a prostitute who smells of “grease and cologne” (14). All this is obscene enough, indeed, but it is what gives the novel its substance. Without it, there would be nothing; by contrast, the transcendent fatherland peddled by the epilogue is a paltry fiction indeed. This has hardly been a novel of “trees and rivers.” It’s not the betrayal that defines and constitutes the book; it’s what is betrayed.

And whatever one thinks of governments and decrees, in fact these are hardly the key elements of the community (however corrupt) that San Camilo, 1936 depicts. If anything, it’s the call and response of radio and multitude that defines the historical situation that Cela outlines. For in the end “in a city of a million inhabitants it’s enough that a couple of dozen listen to the radio, if the rumour comes from a dozen different sources it floods the city in a couple of hours” (161). Rumour, the voice(s) of the anonymous multitude, a collectivity that fucks and shits and fights and stumbles, is what gives life to history and to the city, and ultimately to the novel that parasitically tries to capture it, too.

unas ideas sobre San Camilo,1936

Yo quería encontrar los signos o las pistas de cierto argumento, porque antes de leerlo, sabía que es un libro sobre la guerra civil española. Sin embargo, casi me perdí en los nombres de los personajes y sus anécdotas, los cuales al parecer son irreverentes a lo que yo creí al principio. Es difícil encontrar alguna lógica, mucho erotismo, muchos personajes y muchas opiniones de los personajes. Todo eso me da una impresión que no es lógica para nada sino sentimental, corporal, que la justicia, el heroísmo, las ideologías, la razón, la creencia están lejos del centro de la vida cotidiana, en cambio, son las rutinas, los chismes, el placer, lo corporal, el ego que se importan más para la gente en el libro. Se contemplan a sí mismos charlando en un café con unas mujeres admiradas al lado. Muchas veces hablan para hablar y después del café, les importa poco lo hablado. Son ignorantes hasta llegue su propia posible muerte. Además, me parece que la sociedad descrita en el libro es muy suelta, consiste en diferentes personas y grupos y sus prejuicios, no hay la orden, la gente cuestiona o abandona su creencia anterior y tienden al hedonismo. Sin embargo, no me parece que el autor está atacando contra esta actitud de la gente y su vida, a veces siento que el autor quiere decir que esta actitud, la ignorancia o el hedonismo está inscrito en (nuestro) ADN como una propiedad o debilidad natural y en esencia las rutinas son nuestra realidad. Un día pasa una serie de muertes y se estalla la guerra civil (o cualquier otro acontecimiento histórico), pero nadie puede explicarse el porqué, es como que el acontecimiento es una acumulación de un montón de causas posibles, tan complejo, casual e inevitable, todos están involucrados y pueden ser víctimas y criminales al mismo tiempo, así que no se puede dar una sola explicación.

No puedo distinguir la posición del autor en el libro, para mí, es más bien un pesimista y a veces siento cierto hastío del autor a la política y una desilución. La gente en el libro son como animales y son tan ordinarios que importan poco. Y muchas veces la gente son incapaces de controlar las cosas y son cobardes, hay que seguir teniendo la esperanza pero es la rueda del tiempo y del ¨randomness¨ que mueve el mundo, no es la gente.

¿O de pronto mi lectura es demasiado extremista? :)

Soldados de Salamina

Javier Cercas’s Soldados de Salamina (Soldiers of Salamis) is a hybrid, metafictional (or self-reflective) blend of fiction and fact, novel and history or testimony. It is metafictional in so far as the story it tells is purportedly the story of the writing of the book itself: the narrator and protagonist is a Spanish writer called Javier Cercas who is writing a book with the title Soldados de Salamina. The book (the book we are reading) ends as the narrator, looking at his own reflection in a train window while the day outside fades into night, suddenly envisages the book (the book he is writing) “complete, finished, from beginning to end, from the first to the last line” (206). The book (the book he is writing) can take shape now that the narrator has found “the part that was missing in order for the mechanism of the book to function” (165), that being the story of a former soldier named Antoni (or Antonio) Miralles, which occupies the third, final, and longest section of the book (the book we are reading). The narrator sees his book coming together as he returns home from a meeting with Miralles, as the train hurtles through the dark to its destination, and as the book (the book we are reading) races to its own conclusion, whose final words both refer to Miralles’s wartime campaigns and resonate with the rhythm of the tracks: “onwards, onwards, onwards, ever onwards” (“hacia delante, hacia delante, hacia deltante, siempre hacia delante” [207]).

Rather than taking away from the realism of the text, if anything the metafiction enhances it, making the book seem less metafictional per se (less a fiction about a fiction) than self-reflective: a fact about a fact. After all, it is undeniable that Javier Cercas the author has written a book entitled Soldados de Salamina; we hold it in our hands. So when the narrator, also names Javier Cercas, claims to have done the same, we tend to believe him. Moreover, many of the central elements of the book are a matter of historical record: Cercas hears about Miralles thanks to a conversation with Roberto Bolaño, a Chilean novelist who (in the real world as much as in the world of the novel) lived in a small town in Catalonia not far from (author and narrator) Cercas’s own home. And both the book Cercas is writing and the one we are reading, which the story of Miralles completes, deal with the escape of writer and politician Rafael Sánchez Mazas, who in real life and fiction alike was a founding member of the fascist Spanish Falange, from a Republican firing squad. And when the book (the book we are reading) includes a photograph of a handwritten page from a diary written by Sánchez Mazas (57), this is indeed a snippet from the historical archive, the image of a page written in Sánchez Mazas’s own hand about his time as a fugitive from the retreating Loyalist army.

This dramatic episode from the last days of the Civil War sounds almost too good an inspiration to be true for a blocked writer (as both narrator and author are said to have been): the book, the one we are reading at least, tells us twice that it is a “story that sounds very much like something from a novel” (“una historia muy novelesca” [33, 196]). And yet, we are told even more often, the book that the narrator is writing is not a novel at all: it is a “true tale” (“relato real”), that is (as the narrator explains to his rather ditzy girlfriend), it is “like a novel [. . .] except that, instead of being one long lie, everything in it is true” (66). But of course the fact of the matter is that, unlike the book the narrator is writing, the book we are reading is neither one long lie nor completely true. Cercas the narrator (whose father has just died) is not quite Cercas the author (whose father is still alive). And whereas Sánchez Mazas and Bolaño, for instance, are historical figures much as they are depicted in the book, the same is decidedly not the case for the “missing” part of the narrative, the Republican veteran Miralles. It is as though Cercas (the author) had followed the (alleged) advice of Bolaño to Cercas the narrator (perhaps also Cercas the author): “’You’ll have to make it up,’ he said. ‘Make what up?’ ‘The interview with Miralles. It’s the only way you can finish the novel’” (167).

So, does any of this matter? Well, let’s take seriously the notion that Miralles and the (made up) interview with him were indeed (as we are told) “the missing part to complete the mechanism that was otherwise whole yet incapable of performing the function for which it had been devised” (163). What function does Miralles enable the book to perform?

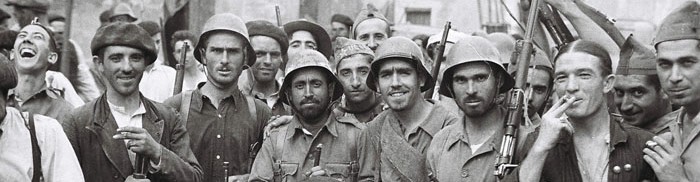

Miralles is a veteran not only of the Spanish Civil War (in which he is on the losing, Republican side) but also of World War Two, in which he fights–ceaselessly, without respite–as a member of the French Foreign Legion, from North Africa to Normandy to Paris (he is in the first Allied unit to liberate the French capital) and on to Germany and Austria. As such, he converts defeat into victory, and what is more (the book claims) we are all in his debt. Three times Cercas imagines him marching to join up with Montgomery’s forces in Libya, “carrying the tricolor flag of a country not his own, of a country that is all countries and also the country of liberty and which only exists because he and four Moors and a black guy are raising that flag as they keep walking onwards, onwards, ever onwards” (192). The tragedy is that his service is now forgotten: the narrator sees people cross the “Place de la Libération” in Dijon “and across all the plazas in Europe going about their business, not knowing that their fate and the fate of the civilization they’d abdicated responsibility for depended on Miralles continuing to walk onwards, ever onwards” (193). Hence the book’s function becomes testimony to this unsung hero, and his fallen comrades, none of whom (unlike the fascist Sánchez Mazas) would ever have a street named after them. But, Cercas tells us, “as long as I tell his story Miralles would somehow live on,” and the same with all his former comrades in arms: “they would live on even though they’d been many years dead, dead, dead, dead” (206). No wonder Soldados de Salamina had such success when it was published in 2001: just as the last veterans of the Civil War were coming to the end of their lives, Cercas gives literature the function of ensuring that their memory, or the memory of their memories, should live on through the documented fiction (or the fictional documentation) of the hunt to record the fragile traces they left in passing.

But without this fictional supplement, without this (supposedly) “missing part” added to a “mechanism that was otherwise whole,” the book would be rather darker and more disturbing–if also substantially more interesting. Because ultimately Sánchez Mazas is a far more complex character than Miralles, and not simply because he is more than a mere literary character, however much his story sounds like something from a novel.

Sánchez Mazas, whose tale Cercas tells fairly straightforwardly in the middle section of the novel, was no hero. If anything, he was something of coward who simply caught a lucky break in managing to flee a fate that he eminently deserved. For who more merited execution than “Spain’s first fascist” (80), the chief ideologue of the Falange, who “had worked during the twenties and thirties harder than almost anyone so that his country would be submerged in a savage orgy of blood” (49)? Yet the book ends up treating him with a strange sympathy, and not only because it focuses on a moment at which–terrified, cowering in the undergrowth of a Catalan forest at the mercy of a Republican militiaman who unaccountably decides not to give him up–he is at his weakest and most vulnerable. For the point that Cercas makes is that even (or especially) in his triumph, in the aftermath of the fascist victory as he rose briefly to prominence in Franco’s regime, ultimately he (too) was on the losing side.

For it is not just left-wing revolutions that are betrayed: however much he refuses to admit or apologize for it, he had “contributed all his forces to igniting a war that destroyed a legitimate republic without as a result managing to bring about the fearsome regime of poets and Renaissance mercenaries of which he had dreamed, but only a banal government of knaves, thugs, and sanctimonious prigs” (132-33). In short the Falange, too, was betrayed by Franco, just as it had urged Franco and his ilk to betray Spain. There is little honour among thieves, Cercas suggests, but at times Sánchez Mazas also emerges as almost a tragic figure who in the end was sold out but also sold himself out as he gave up on politics and literature alike to become the very image of the decadent bourgeois against whom in his youth he had been the first to rebel. “Sánchez Mazas won the war and lost the history of literature,” Cercas quotes Andrés Trapiello telling us, but in fact this was a self-inflicted defeat: he might perhaps have become a great writer, but he ended up merely a good one. And as for winning the war, yes (unlike the fictional Miralles) he has a street in Bilbao named after him, but otherwise he is basically forgotten. Indeed, if it were not for the stunning success of Soldados de Salamina, he would be more forgotten still. The irony is that, though he doesn’t figure in the list the narrator makes of those whose memory the book will perpetuate, Sánchez Mazas lives on in part thanks to Cercas’s novel, which takes its title indeed from the book that (we are told) Sánchez Mazas would have written about his time as a fugitive, but never did. However inadvertently, Cercas finds himself stepping in to complete some part of the disgraced fascist’s legacy.

The character of Miralles, then, though presented as part of a paean to memory and the power of testimony, in fact functions within the novel to help us forget its own portrayal of Falangism. It is a “missing part” in an almost quite literal replay of the Derridean pharmakon: both poison and cure. For however much this book’s explicit narrative is posed against the discourse of forgetfulness promoted by the so-called Transition to democracy after Franco’s death, in fact for much of the time it serves to prove that once you start digging up the past there’s no telling what you may find. Better therefore, as antidote to such unwelcome memories, to invent a caricature hero, indelibly scarred but indefatigable warrior for all the right causes. Cast testimony aside. Don’t look back. Onwards, onwards, ever onwards.

Vísperas, festividad y octava de San Camilo del año 1936 en Madrid

Este libro sin ninguna duda lo calificaría como el más difícil y distinto a todo otro libro que he leído. Al tratar de explicarme por qué es esto a mi mismo, llegué a una conclusión que considero interesante. Todo adjetivo con el describiría tanto el contenido como la voz narrativa y su formato es uno con el cual una persona en un confrontamiento bélico de esta naturaleza describiría su situación. Aún más interesante es que la conversión lógica de esta idea es también totalmente correcta. Por ende, llegué a la conclusión de que la narrativa de esta historia, independiente de mi opinión de sus cualidades como novela, es perfecta para la situación que pretende representar.

A simple vista la confusión intrínseca de esta historia puede ser solo una molestia para el lector (lo fue indudablemente para mí), pero a su vez esto también representa la vida de la persona común durante San Camilo de 1936; exactamente lo que el escritor se dispuso a representar. La persona común, no aquellos bien conectados políticamente, evidentemente vivía en una confusión tal como la que el lector de este texto experimenta.

Especulemos por un momento como sería nuestra vida en aquella situación. Pese a nunca haber experimentado una guerra civil personalmente, ni haber vivido las peculiaridades de esa época, hay ciertas similitudes de este conflicto con lo que yo viví durante la crisis en Ecuador conocida como el 30S.

Lo primero en suceder este 30 de septiembre de 2010, tal como lo cuenta Cela en su caso, es el remplazo de los chismes por las noticias oficiales. Las noticias ni en la actualidad están equipadas para lidiar con una crisis así e informar al pueblo. Sucediendo esto en una época en la que existen medios significativamente más eficaces de comunicación de noticias que durante San Camilo en 1936, recuerdo claramente mandar un mensaje a mis padres durante la mañana de dicho día preguntando qué sucedía tras los chismes que escuché en el colegio.

Lo segundo en suceder en estos casos es el sesgo a reconocer eventos como significativos, fenómeno que se distingue en ambos casos. Pese a supuestamente haberse sublevado esa mañana la policía ecuatoriana, la vida cotidiana (tal como mis clases) continuaron normalmente. No fue hasta que el Presidente de la República fue considerado secuestrado y el ejército entró a la capital que se declaró la situación como grave y se suspendieron las actividades.

Finalmente, y por razones que no deseo discutir seré breve al respecto, me parece que existe también mucha similitud en el modo de actuar de los bandos armados en ambos casos. Para quién le interese (sean advertidos de que es de contenido violento y gráfico), este es el vídeo de la confrontación sobre el cual cual baso mi criterio.

Reconociendo que la crisis que Ecuador experimentó ese día no se aproxima a la Guerra Civil Española ni en magnitud ni duración, en mi experiencia personal corrobora a la presentación de Cela sobre como una persona experimenta estar en una situación de esta naturaleza.

San Camilo, 1936 I

Introducción a Español 430

Réquiem por un campesino español

Lo que me parece interesante sobre Réquiem por un campesino español es el tono de los pensamientos de mosén Millán. Su relación con Paco el del Molino desde nacimiento hasta muerte le da emociones mezclados de tristeza, felicidad y de culpa. Sus recuerdos nos ofrecemos una idea de la personalidad y el papel de Paco en la aldea y de las personas diferentes que afectan su vida.

La culpa y tristeza que siente mosén Millán parece auténtica porque él está atrapado entre su relación con la aldea y su posición como cura en la iglesia, que simpatizaba con los nacionalistas. Sus pensamientos cuestionan lo que estaban sucediendo alrededor de él y cómo la gente debe responder al conflicto. Pero su propio actitud es bastante pasivo hasta la violencia y la miseria. Sus recuerdos muestran una sociedad más compleja que una solo de los ricos y los pobres, una sociedad de sentimientos mezclados y a veces contradictorios. Sin embargo, podemos ver el actitud de mosén Millán hasta la pobreza y la guerra. “Cuando Dios permite la pobreza y el dolor -dijo- es por algo” (p. 16). Él acepta el mundo como es y no intenta cambiarlo u ayudarlo.

Sender intentó de recrear el incertidumbre y la ansiedad que sentía España durante este periodo, enfocado en las tragedias personales, los valores variados entre clase y profesión y la culpa de la iglesia. La tensión entre Paco y mosén Millán refleja la tensión entre los jóvenes reformistas que deseaban reorganizar la sociedad para ser más justa, y las élites que veían los cambios como una amenaza o la pobreza como parte de un plan divino. El deseo de Paco de ayudar y encontrar soluciones a las problemas de la gente contrasta con el actitud pasivo de mosén Millán, y esto es simbólico de las divisiones sociales, culturales, ideológicas y generacionales dentro de la sociedad española. Réquiem por un campesino español muestra un microcosmo de esta sociedad en los recuerdos del cura y toda la tensión social sentida por todos antes de la guerra. El libro me parece sobre todo una crítica de la iglesia y su cooperación con los nacionalistas contra los intereses del pueblo durante la guerra. La culpa que siente mosén Millán sobre la muerte de Paco es la culpa de la iglesia por apoyar a Franco.