|

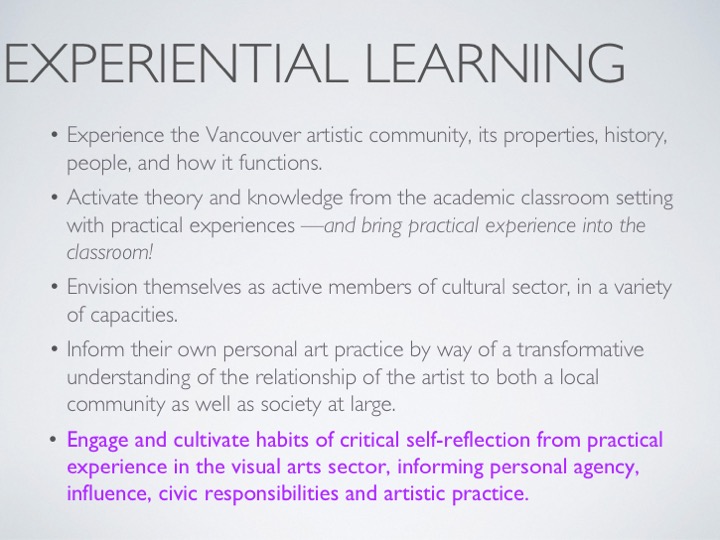

I use experiential learning as a pedagogical method by partnering students with various institutions and artists from the Vancouver art community. Over the last 4 years I’ve partnered approximately 100 students with over 30 different art institutions, artists, and art events. The projects the students complete have included a variety of experiences, including an artist assistants, youth educational and adult programming in galleries, fundraising, publications, curating, archiving, writing, photography, and more. |

|

Experiential learning works well when it is accompanied by academic course content, which I do by way of readings, lectures, discussions, etc… I do this through particular topics related to various student experiences, they are; the role of the artist, role of the studio, gallery systems and art events, art and writing, the artist as activist and the artist’s labour. This expands the experience beyond what you would find in an internship or co-op, as they bring the experiences they have in the community back into the classroom where they are critically activated. |

|

Experiential learning values knowledge of the community, and allows that knowledge to be accessed and then brought into and discussed in class. I am a firm believer in is reflection and it is continuously regarded as a best practice as it is the process that helps students connect what they observe and experience in the community with their academic study. Dewey, in his idea that all knowledge is experiential, claims that in reflection, “the resolution of various instances of experience and adjustment become intellectual.” As well, reflection it integral to the development and evolution of an artist, the method should be habit. |

|

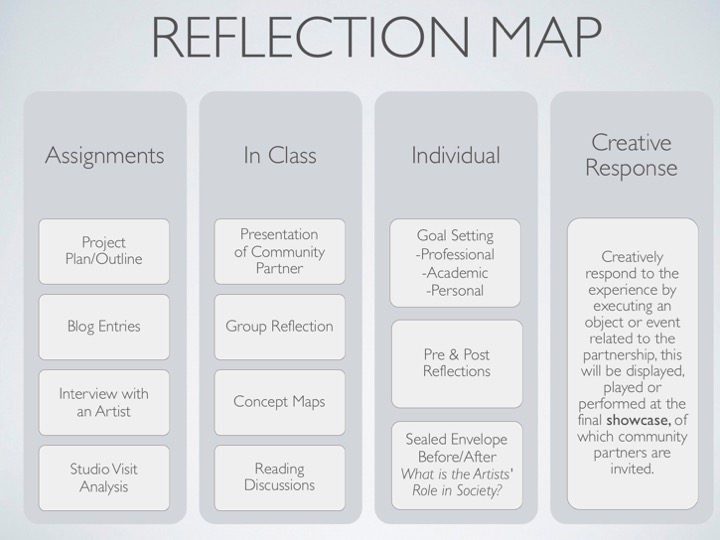

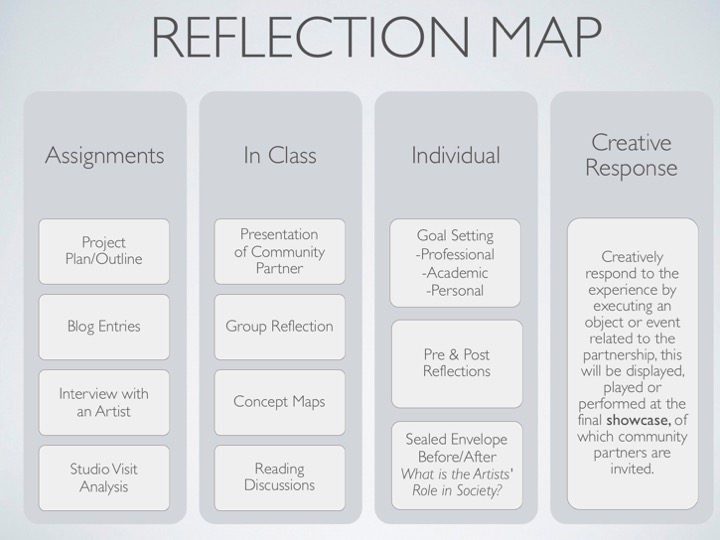

As Janet Eyler warns “if the objectives of experiential learning include such cognitive goals as deeper understanding of subject matter, critical thinking, and perspective transformation–intensive and continuous reflection is necessary.” Taking from many of Eyler’s recommendations on best practices in activating reflection, I developed continuous reflection before, during and after their experiences, in a variety of ways, in groups and solo work, individually and in class. Not always popular, the reflective assignments successfully created challenges to encourage learning, forcing students to confront their own assumptions and pursue difficult questions. |

|

The two reflection activities I will be talking about specifically for this talk is the creative reflection, and envelope exercise.

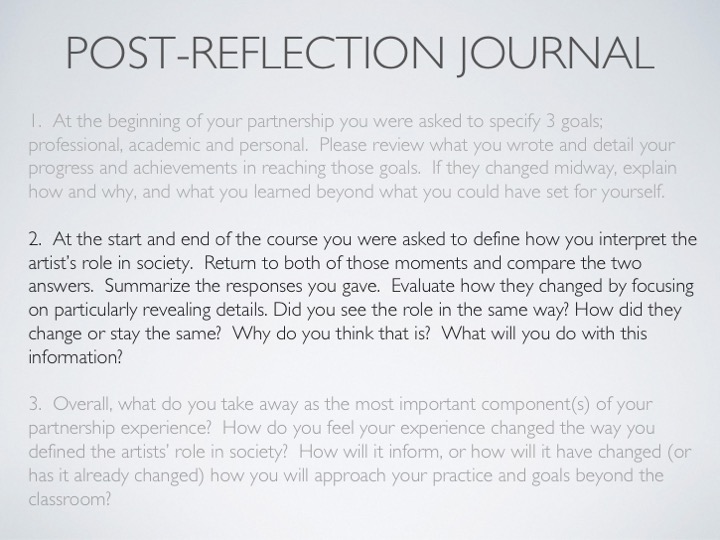

The envelope exercise started at the beginning of the term, before the experiences with community partners started. I asked them to answer the question “How would you define the role of the artist in society?” I then asked them to seal it shut, and then kept it in my office. At the end of the term, after their experience, I asked them the same question again. |

|

After students answered the second time, I gave them back both answers which they would need to complete one of the questions in their journal. I asked them to compare the two answers, and to notice how their definition of the role may have changed and why. Reflective assignments help students “make meaning of experience” (Bringle & Hatcher), and this did so by a deliberate negotiate of how they changed because of the experience, giving evidence of how their next step might go, or –what they would now do with that information. |

|

The final reflection in the class is a creative response project, where students are to execute an art object, event or performance as an approach to reflection, and display it in a final showcase party, this is an invitation to the event. I wanted to activate ‘making’ and demonstrate the value of poiesis, the transfer of intuition to intellect, as an approach to dissecting experience and assess engagement with praxis—unifying theory and action, opening up new possibilities of knowing. |

|

I’ve chosen two students answers to the envelop exercise, as well as their creative response projects, to focus on for this presentation, I am asking:

What is revealed about student learning when conventional teaching boundaries are informed by the disciplinary perspective of Visual Arts, enacting practice based research? How does this process work in reflection? Beyond the written, into praxis? |

|

Andrea Fraser accounts an amusing definition of artistic research by another (unidentified) artist in a recent interview in ArtNews. She accounts “I just heard a funny definition of artistic research: you make a bow and arrow, you shoot the arrow in the air, you go find where it lands, and then you draw a target around it.” Let us uncover some of the targets drawn. |

| The first student I will focus on is Matthew Ballantyne working with VIVO, a long-standing artist run centre in the city. Matthew wrote interviews for artists whose work was in the archive, to respond to in order to activate the works into a new understanding. After intense research of the history, lives, and watching their work in the archives, Matthew wrote up quite meaningful and intelligent interview questions for seven artists. For reasons beyond Matthew’s control, the response by artists was lagging, dismal, and at times met with dead silence. This was undoubtedly disappointing to Matthew. |

|

As Rudge and Chiappin explain of experiential learning “it is important to acknowledge that often students gain knowledge and skills that educators could never fully anticipate, quantify – or assess. Yet it is these gains which may, in the years to come, be some of the most memorable and enduring learning of their entire study experience.” I agree very much with this sentiment and find that the experiences you could never have planned for become some of the most valuable. On the slide is an excerpt from Matthew’s reflection dealing with the outcomes of the project, and revealing his new insight. |

Matthew “Tell it like it isn’t”

turned into

“…try again, fail again, fail better…“ |

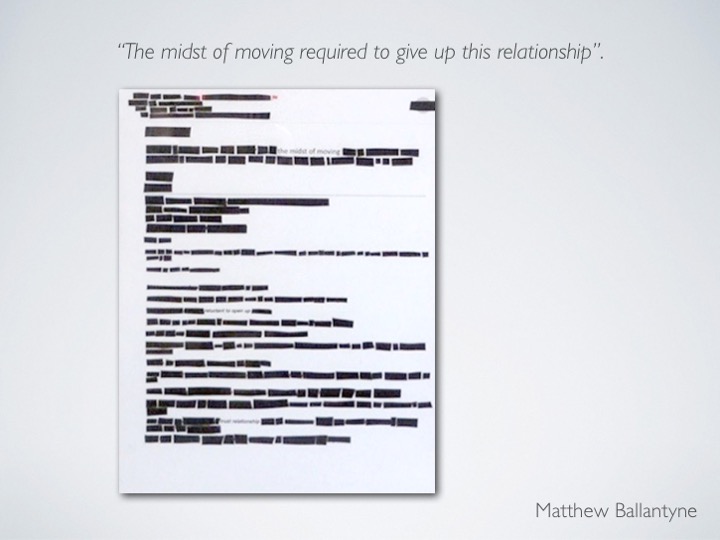

For the creative response, Matthew printed out an email interview correspondence with a certain artist (whose identity is never revealed), and turns the email correspondence from his partnership into a material investigation of bold black mark marking composing the page by the covering up selections of written text underneath. Referencing a long lineage of works using redaction by artists such as Man Ray, Jenny Holzer, to name a few, the beurocratic gesture conceals from those who are not authorized to view, it refers to censorship and editing, in secrecy but not destruction. It also leaves us with something new, under the weight of the administration of art and life via emails. Matthew leaves us with a poetic moment in a new arrangement of the artists words “the midst of moving required to give up this relationship.” |

|

Matthew’s first definition of the artists aim or purpose in society “should be to tell it like it isn’t, which is a way of desiring more from ourselves and our systems.” His second answer of the artists’ role was to “try again, fail again, fail better” borrowed from Beckett, he says “it resonates with me, because I know that it’s not in the “endgame” but in the action. To make art is to try, to hope and to fail, but to use each failure as a motivation to keep trying because to resign to allowing one’s spirit to be stamped out seems a far worse fate than being a perpetual failure.” |

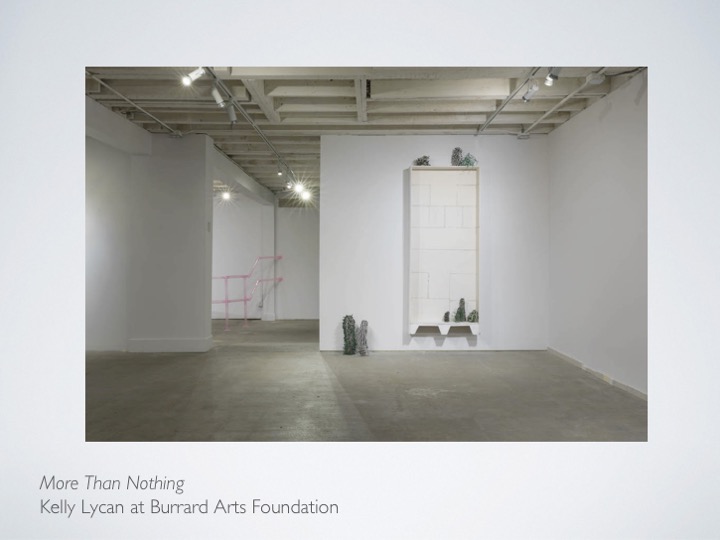

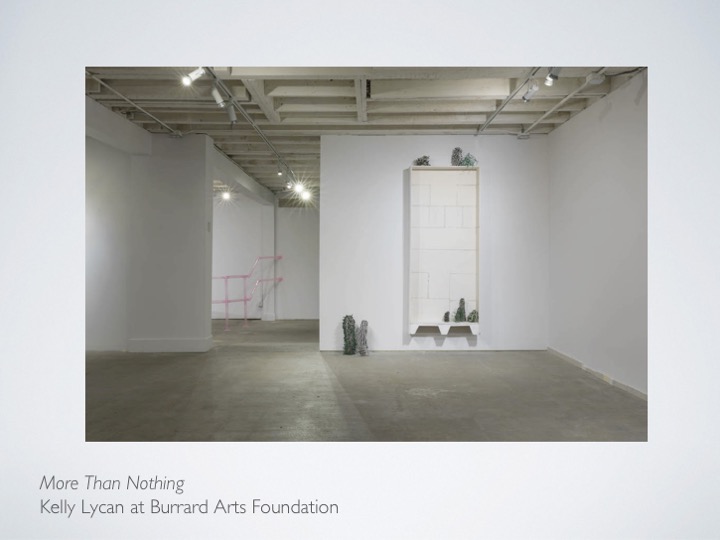

| The second student I will focus on is Simranpreet Anand and her partnership with Burrard Arts Foundation, a local, privately funded gallery in the city. The gallery hosts artist residencies that turn into exhibitions. Simran’s partnership was to introduce educational programming for the show More Than Nothing by artist Kelly Lycan. Lycan used her residency to collect images of display systems from museums worldwide, and have this research and archive inform her exhibition. Lycan found that the drywall and house paint were materials most available in all galleries, which is usually overlooked. She was interested in the crossover these materials had with items found in domestic spaces, the two become conflated in a residency situation. |

|

Lycan used drywall as the subject of her work. Shelves were cut out of drywall -suggest an empty reference- lack of objects, empty shelves asking to have the blanks filled in. Around the mid-way point of the show, Lycan had artists come in and fill the shelves for the duration of the exhibition. The objects in the image were placed in by Lucien Durrey, and it activated the shelves to “hold” again. The walls made from the background are made visible, only to be invisible again as they take on purpose and function of holding something else. This speaks to ways in which work are interpreted, and how one’s frame of reference is automatically a part of the evolution of understanding the work. |

|

Simran went from

“…what an artwork should do or convey…” to “…role of the artist is to dialogue with the world, the role shifts and changes and overlaps, blurred boundaries between art and life…“

|

Simran’s re-iteration of Kelly’s work in her creative response acted out the prospect of reflection as action. She did not make a product of ‘art’ but instead embraced process of practice, forms used to set up discursive propositions. This followed in her reflection as well, where her first answer to the question specified that the role of the artist existed solely in relation to the executed work or object, in her words “what an artwork should do or convey.” Simranpreet’s revised answer at the end of the term indicated that the artist also has a responsibility to interact with society and to negotiate the world outside of the realm of art. She says “art is not created inside of a bubble, and it is the responsibility of the artist to engage with and respond to the world they are creating work in.” She expanded the notion of artist as one who dialogues with the world, the role shifts, changes, overlaps, and blurs boundaries between art and life. |

|

Artists engage with material, form, time, ideas and affect are in the process of ‘making’, a generative mode of action, showing nuanced and intimate thoughtfulness, and recognition of new potentials. As Katja Legin proposes “developing artistic practice and research is obviously not about finding a definite answer; rather, it involves a constant searching for something, a process, a path, and our capacity to walk through and enjoy this, sometimes difficult path. If we speak of research, it means switching our expectations, we will not necessarily come to an unambiguous all-embracing answer, yet perhaps we can push our way to a little more articulated questions and context that ignite in us the desire for further research.” |

|

Students (and perhaps even myself) thought the experience would give them answers, but they soon realized it was more “not knowing”. While the class may have not ‘resolved’ anything, it made them realize how detrimental knowing in one specific way would be. It gave them the ability to handle the space of not knowing, and realize that not everything is easily defined or understood, or how harmful it would be if it was. Students revealed a newfound comfort with the messiness of unresolved situations. The world is messy, tragic, contradictory, antagonistic, and it is by understanding this complexity, rather than trivializing, ignoring or simplifying them, that we can responsibly approach meaning making as the process that happens in praxis. |

|

Looking forward, as I also embrace reflection and process in teaching, I am informed by my students’ findings. One of the biggest revelations I had in my research is that while it was an expectation, experiential learning was not about what questions one could have answered by the end of it, but about the new questions came up. As a result, instead of having students define the role of the artist in the envelope exercise, I will now have them Identify questions about the role of the artist, and then at the end of term, to identify new questions. |