In the last post I discussed how I have come to learn about the different kinds of MOOCs through my participation in etmooc. I also said that through learning about a new kind of MOOC, the cMOOC or “network-based” MOOC, I was reconsidering my earlier concerns with MOOCs. Might the cMOOC do better for humanities than the xMOOC?

A humanities cMOOC

“Roman Ondák”, cc licensed ( BY ) flickr photo shared by Marc Wathieu

“Roman Ondák”, cc licensed ( BY ) flickr photo shared by Marc Wathieu

I haven’t yet decided whether or not one could do a full humanities course, such as a philosophy course, through a cMOOC structure. Brainstorming a little, though, I suppose that one could have a philosophy course in which:

- Common readings are assigned

- Presentations are given by course facilitators and/or guests, just as in etmooc

- Participants are encouraged to blog about the readings and presentations and comment on each others’ blogs (through a course blog hub, like etmooc and ds106 have)

- Dedicated Twitter hashtag, plus a group on a social network like Google+, and a group on a social bookmarking site like Diigo (see etmooc’s group site on Diigo)

- Possibly a YouTube channel, for people to do vlogs instead of blogs if they want, or share other videos relevant to the course

Would this sort of structure be more likely to allow for teaching and practice of critical thinking, reading and writing skills, as I discussed in my earlier criticism of MOOCs (which was pretty much a criticism of xMOOCs)? I suppose it depends on what is discussed in the presentations, in part. The instructors/facilitators could model critical reading and thinking, through explaining how they are interpreting texts and pointing out potential criticisms with the arguments. They could talk about recognizing, criticizing, and creating arguments so that participants could be encouraged to present their own arguments in blogs as clearly and strongly as possible, as well as offering constructive criticisms of works being read–as well as each others’ arguments (though the latter has to be undertaken carefully, just as it is in a face to face course).

This would involve, effectively, peer feedback on participants’ written work. Rough guidelines for blog posts (at least some of them) could be given, so that in addition to reflective pieces (which are very important!) there could also be some blog posts that are focused on criticizing arguments in the texts, some on creating one’s own arguments about what’s being discussed, etc.

What you wouldn’t be able to do well with this structure are writing assignments in the form of argumentative essays. These take a long time to learn how to do well, and ideally should have more direct instructor/facilitator feedback rather than only peer feedback, in my view. Peer feedback is important too, but could lead to problems being perpetuated if the participants in a peer group share misconceptions.

Another thing you can’t do well with a cMOOC is require that everyone learn and be assessed on a particular set of facts, or content. A cMOOC is better for creating connections between people so that they can pursue their own interests, what they want to focus on. Each person’s path through a cMOOC can be very different. Thus, as noted in my previous post, there is not a common set of learning objectives; rather, participants decide what they want to get out of the course and focus on that.

One would need to have a certain critical mass of dedicated and engaged participants for this to work. If it’s a free and open course, then people will participate when they can, and can flit in and out of the topics as their time and interest allows. That’s fantastic, I think, though if there are few participants that might mean that for some sections of the course little is happening. So having a decent sized participant base is important. (How many? No idea.)

I envision this sort of possibility as a non-credit course for people who want to learn something about philosophy and discuss it with others. Why not give credit? There would have to be more focus on content and/or more formal assessments, I think (at least in the current climate of higher education).

A cMOOC as supplement to an on-campus course

Even if a full cMOOC course in philosophy or another humanities subject may not work, I can see a kind of cMOOC component to philosophy courses, or Arts One. In addition to the campus-based, in-person course, one could have an open course going alongside it. This is what ds106 is like. One could have readings and lectures posted online (or at least, links to buy the books if the readings aren’t readily available online), and then have a platform for students who are off campus to engage in a cMOOC kind of way.

Then, those off campus can participate in the course through their blog posts and discussions/resource sharing on the other platforms, like we do in etmooc. Discussion questions used in class could be posted for all online participants. Students who are on campus could be blogging and tweeting and discussing with others outside the course as well as inside the course.

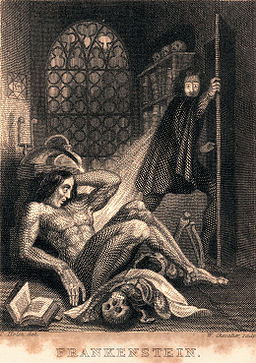

Frontispiece to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1831),by Theodor von Holst [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. One of the texts on Arts One Digital.

Arts One has already started to move in this direction, with a new initiative called Arts One Digital. So far, there are some lectures posted, links to some online versions of texts, twitter feed, and blog posts. This is a work in progress, and we’re still figuring out where it should go. I think extending the Arts One course in the way described above might be a good idea.

Again, the main problem with this idea (beyond the fact that yes, it will require more personnel to design and run the off-campus version of the course) is getting a high number of participants. It won’t work well if there aren’t very many people involved–a critical mass is needed to allow people to find others they want to connect with in smaller groups, to engage in deeper discussions, to help build their own personal learning network.

Looking back at previous concerns with (x)MOOCs

Besides general worried about their ability to help students develop critical skills, I was also concerned in my earlier post with the following:

- In the Coursera Course on reasoning and argumentation (“Think Again”) that I sat in on briefly, I found myself getting utterly overwhelmed by the number of things posted in the discussion board. I complained that I could scroll and scroll just to get through the comments on one post, to get down to the next post, and repeat for each of the thousands of posts. Even for one topic there were just too many posts.

- I felt that the asynchronous discussion opportunities weren’t as good as synchronous ones, which allow for groups to be in the same mind space at the same time, feeding off each others’ ideas and coming up with new ideas. With asynchronous discussions, one might not get a response to one’s idea or comment until long after one has been actively thinking about it, and then at that point one may not be as interested in discussing it anymore (or at the very least, the enthusiasm level may be different).

- The synchronous option of Google Hangouts seems to be a promising way to address the previous point, but I noted in my earlier post that there had been some reports of disrespectful behaviour in one or two of those in the “Think Again” course. I said I thought a moderator would be needed for such discussions, just as we have in face to face courses to ensure students treat each other respectfully.

Can a cMOOC address these concerns?

- From my experience with etmooc, the discussion does not have to get overwhelming. The thing is, each person focuses on what they want to focus on from the presentations, or from what others have said in their blogs, or from resources shared by others. There is no single “curriculum” that we all have to follow, so it’s not the case that everything posted by each person is relevant to everyone else’s interests and purposes for the course. This could be true of a philosophy or Arts One cMOOC as well, so it could be easier to pick and choose what, amongst the huge stream of things to read and think about, one wants to focus on.

- Synchronous discussions are difficult in a large group. In etmooc we have some opportunities for them in the presentations, which allow for people to write on the whiteboard, engage in a backchannel “chat,” and also take the mic and ask questions/offer comments. One could have the presentations have more time for discussion, perhaps, which could take place in part on the chat and in part via audio. It’s not as good as face to face discussions, though–much more fragmented.

- Google Hangouts are an alternative, though I haven’t tried doing one in etmooc. Some have, though, and reported success. However, the people taking etmooc are mostly professionals, both teachers and businesspeople, and they are both highly motivated and responsible/respectful. Having Google Hangouts where anyone in the world can show up could be inviting trouble. I don’t see a cMOOC addressing this problem.

cMOOCs in humanities–what’s not to love?

What other problems might there be with trying to do a cMOOC in humanities, whether on its own or as a supplement to another course? Or, do you love the idea? Let us know in the comments.

UPDATE: I just found, in that wonderfully synergistic way that etmooc seems to work, this blog post by Joe Dillon, which explains how well a cMOOC like etmooc stacks up to a face to face course. It’s just one example, but it can provoke some further thought on whether a cMOOC for humanities might be a good thing.

Once again the allegedly impersonal and disconnected world of MOOCs is turning itself on its head; having just finished reading and responding at a personal level to the post you mentioned (by Joe Dillon) at the end of your latest article, I dove into yours and again found myself fully engaged and nodding in agreement with your comments about how cMOOCs can effectively address concerns about discussions becoming overwhelming, how synchronous online discussions in large groups can be very challenging (but not hopelessly incomprehensible), and how Google+ Hangouts can be a way of connecting online learners with great learning opportunities. Selfishly hope you’re able to explore that humanities course in a way that adapts and applies the best of what we’re learning through #etmooc since I’d love to see how it plays out.

Hi Paul:

Thanks for the compliments here! At this point it’s nothing but an idea in very nascent stages (and Keith Brennan has pointed out some very important concerns to be taken into consideration), but I may bring this up with “co-conspirators” for Arts One Digital and maybe, just maybe, someday we’ll do something like a cMOOC. No clue if or when. It would be a big undertaking, and would take quite a bit of planning to do well. If it happens at all, it would most likely not be for at least a couple of years. And by then…who knows what the world of open, online learning might look like!

Part of what I, in retrospect, valued in doing a conventional philosophy degree was having to engage with ideas, thinkers and traditions that I might not have freely chosen to. Part of the purpose of a philosophy course is to

engage with, and be challenged by points of view and ideas that are contrary to ones own native beliefs and ideas.

Kant, for example. Dreadful, impenetrable style. Unspeakable prose. But necessary reading. Nietzsche. Explosively fun. Camus. Looks great in a cafe with a black coffee and a pack of cigarettes. I knew the girl in the black polo neck would talk to me if I quoted Camus, and would let my buy her coffee if I started talking about giving birth to dancing stars. Less so with the Categorical Imperative I have to say.

I’d also be worried about the development of peer orthodoxies, and artifical polarisation of the community. The Continental/Analytic divide can become fiercely, and depressingly tribal. Our capacity for deindividuation, groupthink, confirmation bias, and selective reasoning is something that can easily find expression. CMoocs operate on something of a meme based transmission protocol, and meme based communication may be particularly prone to this (acceptance into a community is seen or experienced as dependent on acceptance of a meme, a meme in it’s simplest twitter based form is fairly unsophisticated, a badge of belonging – I’d argue aspects of Etrmoocs discussions re Rhizomes might qualify here ).

Threshold concepts – those concepts which provide the key to understanding a discipline, set of ideas, etc – can also be troublesome concepts. Ideas which are counter-intuitive, difficult to master, demanding, and plain hard, may be avoided, misconstrued, dismissed, or reinterpreted.

For the relative novice, choosing a focus is going to help deal with the mass of information issue, but the nature of that choice may be somewhat difficult, and possibly even limiting. Will scientists, for example, tend to go with logical positivism and ignore metaphysics. Will students with religious beliefs go with Kirkegaard, and ignore or discount Nietzsche. Part of how we legislate and necessitate critical engagement in philosphy (and other humatiries) is by requiring students to complete critical work defending their perspectives that has to stand the test of expert scrutiny. If you think metaphysics should be confined to the dustbin of history, you need to back it up, argue, and have read metaphysics. I think this depth of engagement is more unlikely in a cmooc. Here a contextual example from Etmooc might be apropos. In all the talk of pedagogy, there’s not a whisper of Cognitivism (what’s the psychology/neuroscience behind Connectivism, is there a mechanism underlying the theory), Instructionism (how is scaffolding/feedback being/not being deployed and what does that mean) or Behaviourism (how is the Behavior of people altering). Which is odd.

These problems may not be universal. But they probably will occur. And they may compound one another.

All that said, bricks and mortar humanities departments are hardly immune to tribalisation, confirmation and selection bias, enforced orthodoxy and groupthink.

Awwww…you don’t think quoting Kant can be a good way to make yourself attractive? :)

Seriously, though, I see your point, Keith. I don’t think, by any means, that a cMOOC in humanities such as I’ve suggested should replace on campus courses, for many reasons. Good to point to one here: in a cMOOC, you focus on what you’re most interested in, and that means you may be creating your own “filter bubble” and not being critically challenged in ways that we’ve discussed earlier. Same for the point about memes, peer orthodoxies…we’ve talked about this before, and I completely agree (for anyone interested, discussions along these lines can be found here).

Thanks for pointing these issues out again, though, as I got a bit carried away by my love of my experience in etmooc in the last couple of blog posts. I forgot the drawbacks of cMOOCs, which of course are similar to those I pointed out *myself* about rhizomatic learning!

Ultimately, I think that for philosophy, a face to face course is probably the best option, but I also think there could be some value in a cMOOC in philosophy, even with the drawbacks you note. As you point out, those drawbacks happen in face to face environments as well, but are probably compounded in cMOOC environments. Students choose courses in a brick-and-mortar institution they are interested in, and it’s possible to more or less tune out for discussions of philosophers one dislikes. Even if one has to write an essay on those people’s views, it’s possible to treat those views superficially. We can require that students back up their views with arguments, but that doesn’t mean it always happens well. Still, I see that such requirements are not going to be realistic in a cMOOC.

I think it could be possible for the facilitators of a cMOOC to be more active in bringing in resources that might help to break up memes, to have more in the way of competing views presented, and to facilitate constructive criticism (in part by having modules–I dislike that word for some reason–on reading, constructing, and criticizing arguments effectively and constructively). Perhaps the facilitators could blog themselves, and offer some criticisms of what have become memes themselves. And be more active in constructive criticism on some participants’ blogs. It’s not easy to do this well, and one runs the risk of making others feel like they don’t want to contribute anymore, but if the course is done well then hopefully participants will see that criticism is all part of the process of learning. What a challenge, though, to do that well.

I hope, though, that a balance could be found (seems I’ve said something like that before!) between giving people access to content and discussions openly, letting them have the freedom to choose what they have the time/inclination to do in their busy lives, and yet challenging them and encouraging reasoned argument. How to do that, though, I don’t yet know (seems that’s a common refrain with me as well).

Thank you, Keith, for keeping me honest here and reminding me of issues I had put by the wayside for the moment.

Hello Christina,

Thought I would leave a comment on your blog rather than Google+ as I am learning to use all platforms in #etmooc. Regarding ‘critical mass’ for an Arts One cMOOC, UBC may have to look for ‘new audiences’. UBC may be able to more closely serve its own catchment areas (more deeply penetrate the communities in which it is situated). For example, I live on campus and as the campus is now a Univercity, UBC may be able to offer the cMOOC to the campus residents or more local audiences. The same may be true for UBC Okanagan. Adult learners form the bigger target market now as the HS grad demographic is shrinking for univ. FTE’s. On the other hand, your cMOOC idea may also be attractive to a global market. A collaborative initiative may also work-pairing up with another univ. to offer such a cMOOC. One other idea is to offer the cMOOC to BC Gr. 12 HS students as an intro. to a univ. course. You could also look into development funding through BC Campus for such an initiative.I serve on our Faculty’s Communication and Mktg. Cmte (have for years) and I know that it is really important to wed faculty course /program development with effective marketing.

Hi Janet:

Very intriguing idea to reach out to the local audience of the on-campus “town.” Of course, the cMOOC is available to anyone, anywhere (though time zone differences make synchronous interactions difficult!), but why not more pointedly reach out to people right in the local neighbourhood? And also the surrounding cities.

I also like the idea of pairing with another university. I had already thought of something along these lines: there are several programs in Canada that are similar to Arts One (though all have their differences), and at the very least we could create a blog hub aggregating students’ blog posts on each book. Then, when we are reading the same books, students could comment on each others’ blogs. But I like your idea better: why not try a more official partnership for something like a cMOOC on “foundational” texts in humanities (or “core” texts, or “great books,” or what have you). The only problem would be that each program has different texts they’re studying, so it would be harder to have it go alongside the face to face courses. But it could be done separately from the campus courses.

Finally, the idea of offering it to H.S. students is excellent, and could actually help Arts One with recruitment. If students enjoyed the less formal course, then perhaps they’d be inspired to take the face to face version of Arts One (or, if it were offered in conjunction with one or more other programs, it would offer exposure to all programs).

All of these are great ideas. I’m just now in the brainstorming phase, and not sure the whole notion would work, but I am so appreciative of your thoughts here.

I really like this discussion about the practicality of using rhizomatic concepts in the humanities class, as I teach in the humanities, and I agree that implementation can be problematic, just as in traditional classes, as Keith Brennan notes. Still, I think it’s worth trying, perhaps a bit at a time.

First, I like Cormier’s idea that the community is the curriculum, as it turns away from the traditional notion that the teacher is the sole source of value in a class, supplying (in the extreme case) all the content, all the knowledge, all the assessment, and all the grade. The student adds little value to the class other than presence and is assessed mostly on how much value they take away in their memory banks. Rhizomatic education opens the doors for students to bring their value to the class. A general course in philosophy, then, might encourage a business major to connect epistemology to modern business practices. I’m a firm believer that if a student doesn’t connect new knowledge to what they already know and to their own interests, then they are not likely to keep that knowledge. A class might also open itself to a variety of media and tools, so that a film major, or someone who is simply a film buff, can make a video for a class, or a play, or program a philosophy game. This suggests, then, a change in traditional assessment which tends to be a measure of the efficiency of information transfer (an 83 on a test is such a measure). Let’s look for ways to measure the value students bring to the class, not just the value they take away. I think it takes a more rhizomatic approach to convince students that they actually have value to contribute. And it takes convincing, as they’ve had years of training in classes where only the teacher added value.

Hi Keith:

I completely agree with the point that it makes no sense to think only the teacher brings value, or the most value, to a course. How many times have many of us said, or heard others say, in all honesty, that they learn as much from their students as their students learn from them? And it’s true (or should be). So yes, opening up a philosophy (or other) course to a wider audience could bring even more value to the learners through adding people with new perspectives. Though one might reach a point, depending on how massive the course ends up being, where students start to form smaller groups because the whole group is just too big. The value of adding more and more learners has a limit. Still, one might have people in one’s course, commenting on one’s blog posts, e.g., that one might never have in a traditional class. It wouldn’t be just college students talking to each other, hopefully.

I appreciate that in order to learn and retain knowledge, one has to connect it with something else one knows (at least, that makes sense to me), but there is also that danger of focusing too much on the kinds of things one already knows and what one is interested in, as Keith Brennan pointed out. There should be a way to walk the edge between linking to past knowledge and current interests and being nudged to move beyond those to think critically about them rather than staying comfortably in what already makes sense and seems meaningful.

Finally, I agree that opening up assessments can be a good idea, and am starting to think about doing this more; but I can’t help but also firmly believing in the value of learning to write well. It’s just so useful in so many contexts, and I think it might be helpful for thinking more clearly (it is for me). And good writing takes time and practice! So I am not going to give up on requiring essay writing in my courses, at least not yet. (I talked about this further here).

Thanks for your thoughts here, and the push to recognize the positives of connectivist and rhizomatic methods.

Thanks for sharing this post with the h817 community. I agree that there are lots of ways in which cMOOCs could enhance philosophy and humanities courses, providing we think carefully how to help students challenge themselves (or be challenged) out of those ‘filter bubbles’. More strongly I think every campus based course has a responsibility 1) to offer opportunities for their own students to build their capacity for lifelong open learning and contribution to others’ learning – and getting them to seek out and engage with other perspectives through MOOCS etc is a good way to do that; and 2) to open up some elements of their courses to a wider community

Hi Pauline:

I like your points (1) and (2). I think it would be great if more courses actually were thinking about learning beyond that particular class or beyond their higher ed experience, though I don’t know how often that’s true. My own experience with a cMOOC showed me that it can be useful for that, though there were quite a few people who did not find the experience engaging or useful, so one would have to really be aware of what can end up NOT working and try to address such issues. In the off-campus environment, people can just easily drop out if it’s not working for them, but not so in the on-campus environment. I am starting to see the importance of (2), though I’m embarrassed to say I haven’t in the past. Not sure why…it just didn’t seem like anything that needed to be done. But now that it’s so darn easy to do, why not? Well, I should say it’s pretty easy, but it DOES require a considerable amount of work if you really want to open up a lot. Just posting some of your materials is easy, posting videos of lectures isn’t too terribly hard either (though it can cost money to record them). But opening up a whole course to outside participants in the way I’ve suggested here does take a good deal of work in terms of planning as well as ongoing interactions and addressing issues as they come up. So though this is something I’m thinking of doing, it will probably be at least year before anything comes of this idea.