In Arts One this week we read Angela Carter’s collection of short stories entitled The Bloody Chamber. I really enjoyed this collection, though I found it challenging because we could have spent at least an hour on each story rather than talking about the whole book in two 80-minute seminar discussions. Each story has so much going on in it, so much complexity and symbolism, that I found myself thinking each one was as full as an entire novel itself.

One thing I wanted to talk about in seminar but didn’t get the chance to is the many references to mirrors and reflections. And, since our theme this year is Seeing and Knowing, I really wanted to at least write a blog post about this theme. Here are some of my fairly fragmented thoughts, fragmented partly because I don’t think mirrors and reflections necessarily have the same meaning across all stories.

Beauty is truth’s smile …”, Flickr photo shared by Beverley Goodwin, licensed CC BY 2.0

Seeing in mirrors others’ images of oneself

I got the sense in at least a couple of the stories that mirrors showed women seeing themselves through how they are seen by others: the reflection showed not the woman’s own view of herself, but how others view her.

The Bloody Chamber

I saw this first in “The Bloody Chamber,” the first story in the collection. On p. 11 the narrator explicitly says as much: after noticing that her husband-to-be is looking at her with lust, she saw herself in a mirror and says, “And I saw myself, suddenly, as he saw me, my pale face, the way the muscles in my neck stuck out like thin wire.” But more significantly, she sees in herself “a potentiality for corruption” (11), which he also sees in her (20).

Later, she sees herself in the mirror after he undresses her, and sees the image of a pornographic etching that he had shown her (15). Given his penchant for pornography, it makes sense to say that there, too, she is seeing herself as he sees her: he is the “purchaser unwrapp[ing] his bargain,” and she a tender “lamb-chop” as in the etching.

What about the fact that their bedroom is covered with mirrors? She saw that she had “become the multitude of girls [she] saw in the mirrors, identical in their chic navy blue tailor-mades …” (14). For me, this brings up how she is one in a string of women he has treated similarly, women he has seen in the same way as he sees her. To him, the women may be somewhat identical: his ring, he says when he demands it back from her, “will serve [him] for a dozen more fiancées” (38). But I’m not sure it’s just his problem (though he is definitely a problem); Carter might be pointing to a more systemic issue, that too often this is how women are viewed and treated, as objects to be seen (he has a “gallery of beautiful women” (10)) and lusted over, and to be used, and used up. The narrator “watched a dozen husbands approach her in a dozen mirrors” (15), and as they have sex, “a dozen husbands impaled a dozen brides” (17). This suggests, I think, a more systemic problem–this happens to many husbands and wives.

Erl-King

I saw this theme again in “Erl-King,” even though there aren’t any literal mirrors in the story so far as I remember. But the narrator speaks of her reflection in the Erl-King’s eyes (both of the following are from p. 90):

The gelid green of your eyes fixes my reflective face. It is a preservative, like a green liquid amber; it catches me. I am afraid I will be trapped in it forever ….

Your green eye is a reducing chamber. If I look into it long enough, I will become as small as my own reflection. I will diminish to a point and vanish. … I shall become so small you can keep me in one of your osier cages and mock my loss of liberty.

Of course, much of this story is about being enclosed, being caged: “The woods enclose” (84 and also 85); she felts she was “in a house of nets” in the woods (85); he takes girls and cages them as birds. What I find interesting here is that part of the caging is through his eyes:

I know the birds don’t sing, they only cry because they can’t find their way out of the wood, have lost their flesh when they were dipped in the corrosive pools of his regard and now must live in cages (90).

Connecting this with what I said above about “The Bloody Chamber,” I thought of the narrator speaking of her reflection in his eyes as a kind of entrapment. Then I considered that perhaps, again, the reflection could be symbolic of the view of these women from the perspective of the male figure, which holds them in a particular image that they have trouble finding their way out of. The narrator, at the end, plans to find her way out, though; still, she has to ask him to turn his gaze away first before she can do so.

Seeing only oneself, one’s own reflection, when seeing others

This is related to the above–it’s more from seer’s standpoint than what I talked about above, which is more from the standpoint of the seen (being trapped in the regard of the seer).

I saw this in “The Courtship of Mr. Lyon,” though a similar theme can probably be found elsewhere too. There is an emphasis early on with the “Beauty” character on how she sees the lion as so very different from her:

She found his bewildering difference from herself almost intolerable; its presence choked her (45).

It was in her heart to drop a kiss upon his shaggy mane but, though she stretched out her hand towards him, she could not bring herself to touch him of her own free will, he was so different from herself (48).

This makes sense on a literal level of the difference between a lion and a human; she thinks, after all, “a lion is a lion and a man is a man and, though lions are more beautiful by far than we are, yet they belong to a different order of beauty …” (45). But I think that as we read further into the story, another meaning can emerge.

When she looked into his eyes, “she saw her face repeated twice,” which can suggest that when she looks in his eyes all she sees is herself (47). This idea is amplified later when she goes to London and lives a life of luxury: “she smiled at herself in mirrors a little too often, these days …” (49). The “beauty” she sees is when she looks at herself in the mirror: “she took off her earrings in front of the mirror; Beauty” (48).

But then when the spaniel comes to her at the end of winter, “[h]er trance before the mirror broke” as she remembered her promise and that she had broken it (49). And when she goes to him she sees that he has eyelids:

How was it she had never noticed before that his agate eyes were equipped with lids, like those of a man? Was it because she had only looked at her own face, reflected there? (50)

That is the quote that sent me thinking in this direction in the first place! And the ending of the story could suggest that after all him seeming to be a lion could have been because she didn’t really see him as he was: she noticed that “he had always kept his fists clenched but now, painfully, tentatively, at last began to stretch his fingers”; and she saw that his nose gave him a look of a lion (51)–perhaps he just had that resemblance and it was she who thought of him as a lion? And perhaps that is because somehow he was different from her, and she wanted, at first, only sameness, only the sort of being she saw reflected in a mirror?

The view she had that “a lion is a lion and a man is a man” is questioned in numerous stories, I think, given the transformations between humans and non-human animals that happen in many of them. And this connects back to something that was said in the lecture on this book that we had on Monday: Carter may have been trying to get beyond the binary of predator and prey, master and slave, aggressor and victim that is often apparent in fairy tales and in some depictions of sexual relations (such as with the Marquis de Sade). The “Beauty” character in this story at first thinks of Mr. Lyon as a lion and herself as “Miss Lamb, spotless, sacrificial” (45).

- Actually…is this supposed to be her name, as in Mr. Lyon and Miss Lamb? Don’t know…just thought of this.

So she at first has that sort of binary view of their relationship–he will “gobble her up” as the nursemaid of the “Beauty” character in “The Tiger’s Bride” says of the tiger-man (56). But perhaps the “Beauty” of the “Mr. Lyon” story gets past this binary view to some degree when she sees that he is not a lion after all (or perhaps he really turns from a lion to a human when she pulls away from her mirror…it’s hard to tell).

“Wolf-Alice”

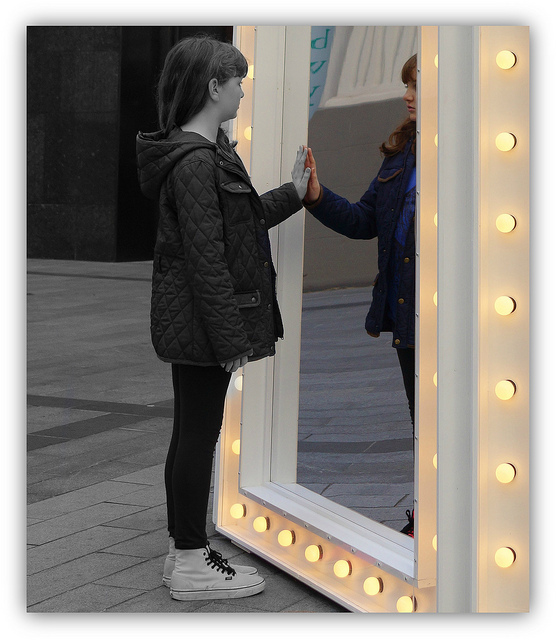

Reflecting Bullmation, Flickr photo shared by 6SN7, licensed CC BY 2.0. Okay, I know a dog isn’t a wolf, but you get the picture.

I am bringing up this story as a separate section because, frankly, I’m having trouble figuring out what to do with the mirrors in it.

The Duke, who appears to be a werewolf, also doesn’t have a reflection in a mirror at first (120), which, as someone pointed out in small groups in class today, suggests he also is like a vampire character. This seems partly because “he passed through the mirror and now, henceforward, lives as if upon the other side of things” (121)–you can’t have a reflection if you’ve passed through a mirror.

- This reminds me of Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass: Alice goes through a looking glass one winter night and finds herself in a garden full of talking flowers and a chess queen, as well as humpty dumpty and others. But I haven’t really thought this through.

I wondered if maybe this crossing over to the other side could be related to him going over quite strongly to the “beast” side. He is an undeveloped character in the story, who is focused only on eating:

At night, those huge, inconsolable, rapacious eyes of his are eaten up by swollen, gleaming pupil. His eyes see only appetite. These eyes open to devour the world in which he sees, nowhere, a reflection of himself (120).

He doesn’t see himself in the mirror or in anyone else in the world—-the narrator says that Wolf-Alice has “as little in common with the rest of us as he does” (120). His vision is limited to devouring.

But then by the end the mirror shows the Duke’s reflection, after he has been shot and lies wounded, and Wolf-Alice licks his wounds. She brings him back through the mirror, back from the other side. Perhaps at this point there is a connection between the two so that in a way, he now has a reflection in the world, someone similar to him in some sense, namely her? Or at least, she has sympathy for him, and he can see something more in the world than just what he wants to eat? The narrator says that as he lies wounded he is “locked half-and-half between such strange states, an aborted transformation,” and that he is like “a woman in labour” (126). To me this suggests he is somewhere on the border of whatever it is that the mirror represents, the border he had crossed through and of which now he is sitting in the middle until she pulls him back over.

By this point in the story Wolf-Alice has moved from mostly animal to more human-like. And “two-legs looks, four-legs sniffs”–there is something about vision in this story that seems connected to humanity. As Alice bumps against the mirror the Duke has passed through (123) and eventually comes to see it as providing her an image of herself, she comes to be more human. She wears clothes and thereby has “put on the visible sign of her difference from them” (125). So one might think that here at the end the Duke passes back over into humanity.

And yet, with this story and this last scene ending the book, I wonder if things aren’t a bit more complex than that. By the end of the story she is still sniffing and prowling like a wolf; she has moved into the territory of humanity, but still retains some of her wolflike aspects. She is “Wolf-Alice,” a kind of in-between being, and perhaps we are to think that the Duke becomes and remains such an amalgamation as well. I see something of a progression in the three stories at the end:

- In “The Werewolf” the people think of wolves as dangerous and the people who turn into them as evil witches who must be stoned.

- In “In the Company of Wolves,” as discussed today in class, the Red Riding Hood character has sympathy for the wolves howling outside, because they are cold (117), and she doesn’t fear the wolf but instead has sex with him. There is some kind of closer rapport happening here, though the girl and the wolf are still clearly separate in the last line: “See! sweet and sound she sleeps in granny’s bed, between the paws of the tender wolf” (118)

- Then in “Wolf-Alice” we might see an overcoming of the binary of beast and human, with a human raised by wolves who takes on some aspects of the human, and the man who became a beast but can then move back into a middle space. But then again, I may be making that up, really; I think I just want to see that, as was questioned in lecture, she may actually have some evidence of moving beyond this binary!

That was quite a pile of thoughts, and I hope they were coherent, and that at least some might be, if not fully convincing, then at least thought-provoking!