The ETEC 521 course is split into 4 Modules:

-

The Global and the Local in Indigenous Knowledge

-

Stereotypes and the Commodification of Indigenous Social Reality

-

Decolonization and Indigenous Intellectual Property Rights

-

Ecological Issues in Indigenous Education and Technology

For each Module, we were asked to source and briefly annotate at least 5 online resources that were relevant to the Module and could possibly help us “fine tune” our final project.

Module 1: The Global and the Local in Indigenous Knowledge

From CBC: Sachs Harbour, N.W.T., teen pens song about uncle’s death, garners thousands of views online

This story, published on September 16, 2017, came to my attention from my Facebook feed. Two years ago, a colleague of many years, left Victoria to take a teaching position in Inuvik, Northwest Territories. Jasmine has been Michelle’s student for the last two years. Because the community that Jasmine is from is so remote (Sachs Harbour in Inuvialuit Territory), she stays with a host family in Inuvik while attending high school. At the time of the recording, Jasmine was part of a program that takes part on a ship that sails through the Arctic in the summer, visiting communities and taking part in cultural communities along the way. Apparently, a student from my school, Esquimalt High, recently took part in this program as it is open to any student that applies, who falls within the age restriction. Until the song went “viral”, Michelle did not even know that Jasmine was a singer-songwriter! Another layer to Jasmine’s viral social media experience, is her mother’s story of attending residential school. Sending her daughter away to school, however, was not an option for her.

From CBC: ‘A punch in the gut’: Mother slams B.C. high school exercise connecting Indigenous women to ‘squaw’

This story was published September 18, 2017. A Grade 9 teacher, using the Teacher’s Guide, distributed worksheets to their students that had students associate racist nomenclature with the person of origin. Apparently, the motivation was to teach students what the ubiquitous terminology of the day was, however, as the mother astutely points out, the workbook is void of context, and fails to educate students about relevant information regarding the Indian Act and the reserve system, amongst other knowledge. Turning to Michael’s essay from this week; “ Educators must help students conceptually focus the mirror rather than a magnifying glass at native people.” (p. 499) This workbook perfectly exemplifies the magnifying glass approach. What also should be pointed out, is that the teacher in question, was likely trying to incorporate the new K-9 BC curriculum that has attempted to bring Indigenous knowledge into every course. As a BC teacher, I can say with certainty, that there has not been enough (any?) professional development to facilitate this change so that BCTF members can actually teach Indigenous knowledge with confidence. I am grateful that I am taking ETEC 521 so that I can hopefully avoid making one of my students or their parents feel link I have “punched them in the gut.” Most teachers will not be paying $1600, however, in order to take such meaningful Pro-D. Moreover, I wonder how many teachers will simply side step this portion of the curriculum in fear of making a mistake? <Segway to next article…>

Marker, Michael, “After the Makah Whale Hunt: Indigenous Knowledge and Limits to Multicultural Discourse”, Urban Education, Vol. 41(5), 2006, 482-505.

From CBC: Teachers lack confidence to talk about residential schools, study says

This story was published August 20, 2017. Yes. This is me. Or rather, this was me. I feel fortunate to work at a school that devotes a portion of our Pro-D time, every year, to Indigenous education and the well-being of our Indigenous students. But still, I do not feel like I know enough to say too much in class. With the Truth and Reconciliation Commission being part of mainstream media, combined with some incredibly meaningful Pro-D, I have begun to say more, however. On Orange Shirt Day 2016, I gave my first talk to my homeroom class about the significance of the day— how could I not? I felt like I had finally broken through my self-imposed, block of ice. It is now three weeks into ETEC 521, and I feel more equipped to say what needs to be said, when it needs to be said. I am looking forward to learning more, however, as I know there is much more knowledge to come!

This is Just Us: A Digital Media Documentary

At my high school, we run a course called First Peoples English, in which any student may elect to take this course, in lieu of regular English. Recently, students created the documentary, “This is Just Us.” For whatever reason, I only just learned of this documentary this week (it is amazing what you can find on your school’s website!). It is a bit of a commitment to watch, however, should you have 38 minutes to spare, you will not regret it. In the documentary, Indigenous and non-Indigenous students are interviewed. As well, a local Elder, one of our school’s Aboriginal Educational Assistants and the teacher of the course are all interviewed. Topics that are touched on include: Why Digital Media? What is self-esteem? Who are you thankful for? … and more! I was blown away with the students’ candidness, honesty, bravery and wisdom in their responses. The Elder speaks of running away from his residential school, seeking refuge in Washington. This really drove home the reading of “Borders and the Borderless Coast Salish” from last week. As opposed to the educator who ran into trouble when they attempted to “teach” Indigenous knowledge using an inappropriate “magnifying glass”, Ms. Dunn helped her students “conceptually focus the mirror”, with this project. The project would not have been a success without the partnership with Dano, an actor and director from Tsawout First Nation. Dano came in once a week for a couple of months, and after getting to know the students, he decided that the common thread was how self-esteem affects individuals, families and communities.

Indigenous Leaders on How to Celebrate National Aboriginal Day

This page was published on June 20, 2017, on the University of Toronto’s website. It interviews a variety of Indigenous Leaders (a student, an Elder, and the former National Chief, amongst others), who share how they plan to celebrate June 21 and what any Canadian could also do to recognize this day. I would like to specifically highlight one piece from this page, that addresses the Canada 150 celebrations. This summer, there was a heap of dialogue concerning whether we should be celebrating 150 years of colonialism. Many people I know chose to boycott all July 1 celebrations, and they were not afraid to make it known to all who would listen. Reading this piece, you will find Phil Fontaine’s (albeit brief) take on Canada 150. I don’t think everyone shares his perspective, however, it does exemplify the power of the “positive re-frame”. That is, when a situation is not ideal or seemingly “good”, by changing our perspective a few degrees, we can sometimes see opportunity past the darkness.

Pacific People’s Partnership

PPP is a non-profit organization that promotes sustainability, peace, social justice and community development for Indigenous peoples from the Lekwungen territory in coastal BC and South Pacific Indigenous peoples. I chose this site because I was able to attend a recent event at the BC Legislature on September 16, 2017, The One Wave Gathering. Five local Indigenous youth won a contest that resulted in their work being displayed on the front of four longhouses that were temporarily erected on the Legislature. The fifth artist’s work was made into a dance screen, as the judges were not able to let his work go unnoticed. Both the Songhees and Esquimalt Nation chief’s spoke at the opening ceremony. Chief Andy Thomas described the history of the land that we were meeting on, and how his Great-Great Grandparents were forced to move their village from Victoria’s Inner Harbour to the Esquimalt Harbour. I was particularly moved by the stories of the young artists and I truly felt the sense of proudness that they had of themselves and that their community had for them. That proudness wrapped itself around everyone in attendance. I will put a couple of my pictures on this blog, however, feel free to check out the Instagram hashtag, #onewavegathering to see other pictures and videos.

Module 2: Stereotypes and the Commodification of Indigenous Social Reality

The Ethnos Project

The Ethnos Project is a research initiative that explores the intersection of Indigeneity and information and communication technologies (ICTs) such as:

- open source databases for Indigenous Knowledge management

- information and communication technologies for development (ICT4D) initiatives

- new and emerging technologies for intangible cultural heritage

- social media used by Indigenous communities for social change

- mobile technologies used for language preservation

The essays found in this site seem incredibly appropriate for our learnings in this course. The founder of The Ethnos Project, Mark Oppenneer, might be a “Wannabe”, however! I tried to learn more about him, only to find that either another person with the same name, or the founder of this page, was fired from his teaching job for inappropriate relations with a student. From Oppenneer’s LinkedIn profile, it appears to be the same person… What intrigues me about this website, is how polished it looks and how interesting the essays seem to be. My question is this: is the founder a “Wannabe” and should this site be not accessed should this be the case???

Knowing Home: Braiding Indigenous Science with Western Science

Anyone who says that Facebook is a waste of time, is not using Facebook to its full potential.

Recently, I joining a Science Teacher FB group and this group has actually revolutionized my teaching in only 4 weeks. Not only have I adopted something called Two Stage Exams, but someone recently posted a link to this incredible resource, Knowing Home: Braiding Indigenous Science with Western Science. What is particularly jaw-dropping, is that I saved this link two weeks ago, long before I watched this week’s video interviews. The co-author of this online book is none other than Lorna Williams!!!!

This book is a MUST READ for anyone teaching science. I have only had time to look at a few of the chapters but the one chapter that particularly applies to this week’s module is Chapter 9: Changing Students’ Perceptions of Scientists, the Work of Scientists, and Who Does Science

This chapter summarizes a study that was done with Grade5/6 students and Grade 11/12 in a First Nations Studies course. The stereotypes harboured by both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students are eye-opening, to say the least. As a science educator, what can I do differently in my practice to help my students see past these stereotypes? Am I do anything that reinforces these stereotypes?

Sask. First Nation chief says tobacco offering from visiting school’s coach a step toward reconciliation

From the CBC, September 30, 2017. Here is the original Facebook post from Chief Evan Taypotat.

People stereotype, consciously and unconsciously– stereotyping is often due to making assumptions, without taking the time to educate oneself of the truth. However, this was an example of someone taking the time to understand Indigenous culture and showing respect, in an authentic way.

Colorado River should have same legal status as a person: lawsuit

From the CBC, October 10, 2017.

In Week 6 of our studies, we were asked if we thought if cultures have rights to protect themselves?

Should the lawyer representing the Colorado River win his case, he may wish to move on to representing culture in the courts, as well! Although the article is a quick read, spending time listening to the lawyer’s arguments in the interview is recommended as it may provide you with extremely compelling reasons that make it obvious that our natural resources should be protected in court, as if they were a person.

Stop believing this myth: No, Native Americans are not “anti-science”

Although this website is highly irritating with its pop-up ads, the article itself is worth a read. I took some time to learn about the Salon website (you know, to check on something called “Authority”…) and according to Wikipedia (I know my credibility is sinking fast now…), Salon.com is a left-wing tabloid style, media outlet. NONETHELESS, I am posting this article because IF what it says is actually true, this article would be very valuable to anyone wishing to “braid” Indigenous science into their lessons. I would highly advise folks to use this as a stepping stone to research more into the topics it provides.

Module 3: Decolonization and Indigenous Intellectual Property Rights

Victoria school district Aboriginal cultural facilitator honoured with music award

Anyone who knows Sarah Rhude knows that receiving an award is not something she sought or yearned after. I talked to my friend and colleague, Jenn Treble, the trouble maker who nominated Sarah, as she was photocopying endless sheets of music for her students, last week. Jenn informed me that the photo of Sarah was snapped after tears decided to run down her face, due to the emotional wave that the ceremony impacted her with.

Three years ago, Jenn decided that she wanted to introduce Indigenous music into her practice and she asked for Sarah’s help. Baby step after baby step, since then, has now led to SD61’s permission to the teaching of three Indigenous songs, that were created for the purpose of the project. All students in Jenn’s band classes, Grades 9 through 12, learn, practice and perform these songs.

Last year, a Grade 12 Metis student asked Jenn, in front of the class, why she was “singling out” Indigenous culture, when there were so many other cultures represented in class. Was he embarrassed? Had he been “colonized to the point of no return”? I am not sure, although I know the student extremely well– he was one of my top math and physics students! It was a non-Indigenous Grade 9 student who spoke up and said, “Because we do not live on Scottish territory. If we did live in Scotland, we would undoubtedly learn about Scottish music. But we live on Lekwungen territory… that is why.”

Enough said.

Why Gord Downie’s ‘beautiful’ work can’t stand alone

My guess is that this will not be the only Hip post this week. I am a Hip fan, although I “only” saw three live shows. Good friends of mine saw well over 20 shows and their now deceased cat was named Gordie.

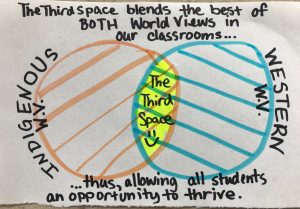

There were many online pieces to choose from over the week, but I went with this interview from CBC’s, Q, recorded on December 7, 2016. The subject was Jarrett Martineau, and Indigenous art scholar and creator of the Indigenous music platform, Revolutions Per Minute. Martineau acknowledges the significance of Downie’s work, and simultaneously underscores the importance of continuing with activism surrounding language preservation and authentic forms of reconciliation. Marineau also mentions how celebrities can bring “different communities together by having them all meet in the middle.” #ThirdSpace

In Canada, white supremacy is the law of the land

You cannot simply reform your racist state by enacting a few more programs and delivering a few more services. It is embedded in the very nature of Canada and requires a completely new deal. But first, to truly understand where we have landed today, we have to continue retracing a bit further along the sad road that brought us to this place. ~Arthur Manuel

Described by some as the Nelson Mandela of Indigenous rights in Canada, Arthur Manuel passed away earlier this year. The above quote was taken from an excerpt from his recently released book he co-authored with Grand Chief Ronald Derrickson, “The Reconciliation Manifesto, Recovering The Land, Rebuilding The Economy.”

Those of us who appreciate history will appreciate this piece. We have touched on some of this history in our ETEC 521 journey, however, Manuel’s perspective offers a dose of reality, that lacks the sweetener.

For what it is worth, when I visited the Human Rights Museum in Winnipeg last summer, I was impressed with the ample amount of “Canada’s dirty laundry” that was put out for public viewing. This piece does not attempt to hide our soiled knickers, either. If the rest of the book is like this excerpt, it will be one “kick ass” manifesto!

Non-Indigenous B.C. artist defends work despite calls for authenticity

If you have been monitoring my posts, I listen to a lot of CBC. Perhaps I should be branching out more with my searches, however, when I hear or read something that is recent and relevant, it really resonates with me, as it allows me to think about historical relevance and how it influences our now.

This column, written by the new host of CBC’s Reconcile This, Angela Sterritt, highlights issues of cultural appropriation and intellectual property rights. The artist in question is from England, and has been “blending” Indigenous art forms with non-Indigenous. The article points out that even though the artist is well-meaning, she is indirectly taking money from Indigenous communities that rely on sales of authentic crafts and artwork. An interviewee continues by saying that “the art market is only so big and we are the most vulnerable demographic, so it kind of stings a bit.”

The History of Dia de Los Muertos & Why You Shouldn’t Appropriate It

“Dear white people, … You arrived at the Dia de los Muertos ceremony shipwrecked, a refugee from a culture that suppresses grief, hides death, … celebrates it only in the most morbid ways — horror movies, violent television — death is dehumanized, without loving connection, without ceremony. You arrived at Dia de los Muertos like a Pilgrim, starving, … and the Indigenous ceremonies fed you … [And] like Pilgrims you have begun to take over, to gentrify and colonize this holiday for yourselves.” ~Aya de Leon

Indigenous peoples worldwide have been fighting off the ramifications of cultural appropriation. This article is a short, history of the cultural relevance of the holiday and why white folks need to stop morphing it into a pathetic excuse to drink excessively and where inappropriate costumes at Halloween parties.

Typically, the comments sections within online pieces are filled with the worst verbal diarrhea know to our species. I came across this comment, however. She nailed it:

“Alana Sterling I truly believe that it IS okay. Cultural appreciation is wonderful. But there is a big difference between cultural appreciation and cultural appropriation.

“Alana Sterling I truly believe that it IS okay. Cultural appreciation is wonderful. But there is a big difference between cultural appreciation and cultural appropriation.

My old high school is thinking about having a day of the dead themed prom. In my opinion that is cultural appropriation because the school is majority white and from experience I know that a lot of them are prejudice and are very outspoken about their feelings on Mexican immigration. Its a small high school in the south.

Cultural appropriation to me is when you want the culture but not the people.

I think if you wanted to throw an actual day of the dead party it would be great look up customs and traditional food and music. That’s appreciation, but if you just want an excuse to wear pretty colors and “sugar skulls” then that’s appropriation. Some people might jump on you for it but to me that’s not really that bad, if you want to throw a day if the dead themed party that’s cool you just need to have respect for your Hispanic brothers and sisters.”~Ayleen DeLeon

Module 4: Ecological Issues in Indigenous Education and Technology

Aboriginal Nations Education Division (ANED) for School District 61

So many amazing resources from my school district’s Aboriginal Education team. You can find pretty much anything you want here, or use this website as a launch point to bring authentic, Indigenous knowledge into your classroom or workplace.

Having said this, I found this resource on this site, that was developed by the BC government in 2006. It targets Kindergarten through Grade 10, and for the most part, looks like a useful document. However, when searching for material for my ETEC 521 paper, I did uncover something that did not sit well with me on p.82. It suggests that in Mathematics 10, that educators and students research the statistics surrounding Aboriginal graduation rates. Although graduation rates have been slowly improving over the years, they are still below the provincial average. An exercise such as this will consequently perpetuate stereotypes amongst non-Indigenous students and potentially send Indigenous students harmful messaging. This document was produced by the Ministry of Education, who used Indigenous community members and educators to assist with its creation, however, at the end of the day, the MOE was the entity in charge of the final product. Who was the person who added this terrible idea to a government resource? In general, it is difficult to find culturally responsive material for academic Math 10, so did somebody “pad” this section without being informed? I find it very difficult to believe that any Indigenous person would think that this was a good idea!!

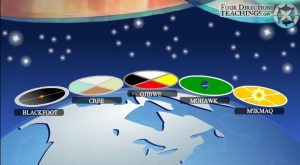

Four Directions Teachings

Click on the image to go directly to this interactive website that shares Indigenous knowledge from five First Nations from across Canada. Drumming, storytelling, sound effects and beautiful graphics are clearly shared and described in these teachings. Be sure to spend time with the Teacher Resource package that is linked on the first page, as well. My only disappointment is that the Coast Salish was not included in this resource, as this would help my non-Indigenous students connect more to the land that they live on and to the people who were here before colonization. Barring that, this seems to be a great site for not only learning about specific Nations, but to also dispel stereotypes that promote pan-Indigenous homogenization.

Victoria’s booming shoebox campaign part of “reconciliaction”

This article was recently posted in the Victoria News, a local, community newspaper. A family of Metis heritage has started a campaign that creates shoeboxes filled with age appropriate gifts for Indigenous youth who presumably are living in poverty conditions, north of Smithers, BC.

Having grown up in a state of lower, lower middle class myself, I think that I would have loved to have received a shoebox full of trinkets as a child. Sometimes when I was young, I did not think that anybody cared about me, and that I was more of a hassle, than anything else. I would imagine that Indigenous youth, in isolated towns, who may not have a heck of a lot to do or to live on, would be prone to feeling this way, as well. Suicide rates in some communities, definitely exemplify this sentiment, in the worst possible way.

So my hat goes off to these young girls who are not only filling shoeboxes and but rallying others to do the same. We all need to feel like somebody cares about us, that is the TRUTH!

However, is it fair for the editors of the newspaper to make a play on words, turning “reconciliation” to “reconciliaction”? Hmmm… that part is not sitting well with me. Is it not the government’s role to “reconciliact”? It seems to me that this family is NOT enacting reconciliation via their noble campaign. True, they are addressing the oppressive, harmful effects that colonization has had on Nations and their people. But this is not reconciliation…

What does reconciliation mean to you?

So what does reconciliation truly mean? Here are six individuals perspectives from a 2016 CBC article. Spoiler alert: none of them mentioned shoeboxes…

This.

My Kiwi Godfather posted this on his Facebook feed this week and I had to share.

“Colonization has forced stereotyping

To become a household name

Which resides under our beds

Becoming the monsters that we are now scared of.”

The raw talent of Kia Kaha is unreal and inspirational. When students are given the freedom to have their voices heard, powerful, life changing moments can and will transpire.