Keywords from every ETEC 533 e-folio post I made:

I have always been a selfishly keen learner.

Selfish, from the perspective that I love to engage in cerebral practices that…

- challenge my current thinking;

- improve my quality of life and the quality of lives of my loved ones;

- keep my career choice fresh and relevant; and

- make me less ignorant of the issues facing society and the world, in general.

I am not entirely sure about where my lifelong quest to learn stems from, although I am certain it is not due to solely one event in my life. Perhaps it has something to do with my parents being educators? Perhaps I had more positive experiences in school than negative? Perhaps I am a pleaser-type— always wanting to make my teachers and parents, and now husband and children, “proud of me”? Perhaps I have a fear of appearing “stupid”? Perhaps I just love to learn!

When looking through my e-folio posts for the course, the theme that has surfaced throughout is “student motivation”. I will further sub-categorize this theme by using the most common words from my ETEC 533 e-folio posts, shown in larger font on the above word cloud: (how we) learn and (how we) use.

Student Motivation and How We Learn

My focus early in the course was on student misconceptions. Without question, one of the most influential readings of the course was Vosniadou and Brewer’s “Mental Models of the Earth: A Study of Conceptual Change in Childhood”. This reading, along with watching “A Private Universe”, really emphasized how students bring in their presuppositions to every learning experience and that their knowledge is situated from needing to explain the world around them (Vosniadou & Brewer, 1002). Prior to this week, I knew that students harbored misconceptions, however, not nearly to the extent that they did and why they did. Understanding that we all have an innate need to explain the world around us, whether it is scientifically based or not, has made me realize that I need to provide more opportunities within my classroom to allow students’ thinking and reasoning to be visible (Linn et al, 2002).

Throughout ETEC 533, situating and anchoring students’ learning has been a key piece that research has shown to foster students’ motivating factors. The well-intentioned, though outdated Jasper Series week got some of us really excited to anchor learning in real life contexts. Reading such blog posts that were titled, “Chalk and Talk are Dead” and “Goodbye Rote, Hello Anchored Instruction” exemplify this excitement to an exciting extreme. Although I will not being giving up my digital chalk anytime soon, what I have extracted from the ETEC 533 experience is that teachers of different age groups have different end goals, and hence, different pedagogical approaches, surrounding their practices.

The situated learning strategies that resonated most with me were via LfU (Learning for Use), T-GEM (Technology-enhanced: Generate, Evaluate, Modify) and embodiment. As summarized using Microsoft’s SWAY program:

All of these models naturally incorporate motivational strategies, that help engage students to want to learn.

Ultimately, students need to not only be interested in what they are learning, but they also need to have the appropriate tools in order to make that learning transpire. Taking into account Scaffolded Knowledge Integration (SKI), in both of the activities that I have produced, incorporating the PhEt simulation for the Gravitation T-GEM and real-time data acquisition apparatus for graphical analysis, every student has an opportunity to make their learning personal and novel (Linn et al, 2002). This concept also reinforces a key takeaway for students who were in the Spicer and Statford 2001 study analyzing the effectiveness of virtual field trips (VFT). Students felt that by participating in the VFT, instead of a traditional lecture, that their learning had been personalized, hence they had more opportunity to engage in independent thought. With curiosity piqued (Edelson, 2000), opportunities for relationships to be generated, evaluated and modified (Khan, 2007), and interactions between the student and environment provided (Winn, 2003), self-motivation can be maximized. In a recent post, I relayed some motivational strategies for educators to invoke:

|

Another key reading for myself was Winn’s “Learning in Artificial Environments: Embodiment, Embeddedness and Dynamic Adaptation” (2003). The importance of coupling students with their environment to foster learning particularly stood out. How can we as educators capitalize on the addictive nature of video games that provide users with appropriate challenge, maximum curiosity, and opportunities to fantasize? Prior to this week, I only considered the affordances of gamification in my pedagogy. Now, I am considering ways of using the effects of video games within my lessons.

From this post: “Activities that challenge students, pique their curiosity and provide “fruitful” new tidbits of knowledge that can assist them with future problems, are optimal, should the new knowledge wish to be adapted (Winn, 2003).”

From the same post: “As the questions would directly relate to the Vernier activity, students would be able to apply their knowledge the next day, making use of all three mechanisms for adaption of knowledge:

-

Creating genetic algorithms: the “if-then” rules we construct when interacting with our environment and adapting our knowledge due to collecting “fruitful” information

-

Rule Discovery: rules would have been crafted during the Vernier activity but then further entrenched by applying the rules to the Peer Instruction questions

-

Crossover:applying the algorithms and rules in new situations could lead to rules combining into new rules for more complex situations (Winn, 2003)”

Student Motivation and How we Use

Wanting to dive into addressing student misconceptions deeper, I chose this topic as my theme for my annotated bibliography, “Shut up and Calculate” Versus “Let’s Talk” Science Within a TELE”. The biggest takeaway from the annotated bibliography was understanding the new roles that educators can be adopting in non-chalk-and-talk learning environments. Previously, the term “Guide on the Side” made me very uncomfortable as my interpretation of what this role entailed was limited to inquiry roles. Now, understanding the merits and dangers of using student-generated analogies (Haglund & Jeppsson, 2013) and stepwise problem-solving strategy (SPSS) (Gok, 2014), will shape my new role as “guide”.

Although I will be putting student-generated analogies and SPSS to the test in the near future, one approach that I have already adopted this semester with all three of my current classes is what I have coined as “Collaborative Quizzing”. In an attempt to create more opportunities to allow students’ thinking more visible, I now allow students to have the option of completing their quiz with a partner. This idea stemmed from our week learning about the WISE platform. Throughout the platform, inquiry lessons require students to reflect on their learning and to provide opportunities for students to engage with each other about the topic at hand.

From this post: “Personalizing lessons within WISE, conducting class discussions, pushing students to think outside of their comfort zones and acting as the MKO (More Knowledgeable Other) at times, are all important actions and roles for educators to adopt.”

Collaborative Quizzing also came about from watching academically vulnerable students, course after course, year after year, sit through quizzes with their pencils or heads down, or with doodles of sadness strewn throughout their paper. These students will spend 20 to 30 minutes in misery, likely either negatively self-talking or in complete surrender. This is not good use of class time. As a self-described underdog, one of my goals as an educator is to help those who need the most help. So with WISE in my toolbelt and an eagerness to make class time effective, Collaborative Quizzing was born! I am particularly fascinated with the students’ feedback on the process. Overall, the feedback has been positive, and to help meet more students’ needs, I am now making the process voluntary.

As far as assessment is concerned, quizzes did not count for marks in my class, however, what I now do is require all students submit their quizzes after they have corrected their own. I provide answer keys during the class time and upload the keys onto our Google Classroom, for those students who need more time or for those students who were away. Students receive full marks for fully corrected quizzes, as opposed to how many questions they initially got right. Increased learning interactions with peers not only build on Vygotsky theory, but also LfU theory, in that students are receiving communication directly from their MKOs to aid in the construction of knowledge (Edelson, 2000). It is theoretically possible to then immediately apply the newly constructed knowledge during the quiz and throughout the practice work that the struggling student is likely behind in.

Concluding Thoughts

Perhaps the most significant shift in my pedagogical approach to teaching math and science has been in how I utilize class time. Although five months by post-secondary standards is a very long period of time, in high school, this time is very limited. During those five months, we teach, reinforce, provide practice time, allow for reading time, show videos, quiz, test, conduct labs, have assemblies, go on field trips, and more. Like a bedroom closet cannot continually have pieces added to it without being dysfunctional, educators cannot continually add activities to their courses without running out of time. However, at the Grade 10 to 12 level, a reasonable expectation exists that students can and will perform some classroom responsibilities outside of class time.

With the adoption of Google Classroom, I now conduct my labs on Google Docs. Partners can collaborate outside of class time more easily, allowing for more constructive activities to take place during class time. I have also reduced number of required practice questions with the intent of reducing the amount of in-class “worktime”, freeing up class time for more collaborative reinforcement activities. Essentially, I am eliminating or reducing individual study activities that are in-class, in exchange for collaborative, technology-enhanced in-class activities.

Photo by Gerberkun courtesy of Imgur.

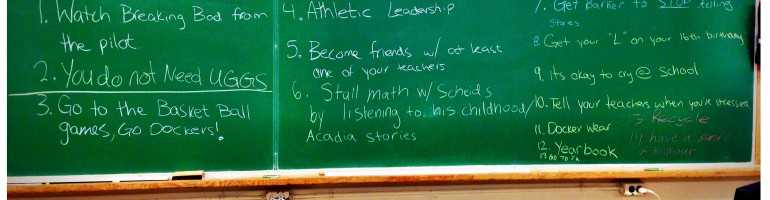

In an earlier post, I included the following image:

Motivating people to want to learn is a task that is very difficult and at times, impossible, should the approach taken be ineffective. I do not believe that my grade levels and subject areas allow for students to pick topics that they are interested in, therefore, I need to be creative in how the material is presented and reinforced. I am very eager to take my pre-existing TELEs and make them more “T-GEM”-ized, as I did with “Conquering Mount Gravitation” and more embodied and LfU-ized, as I did with “Life on the Descoast” and “Graph Matching with Vernier”.

What is unquestionably working to my advantage in terms of motivating students to learn in my classes, is that there are not too many teachers in my school that are embracing TELEs. When students come into my class, my approaches are extremely novel and their curiosity and interest receive instant kudos—whether the lessons are effective or not. As I continue to push my personal TELE envelope, I will continue to refine and question my lessons’ effectiveness. Educators are so fortunate to have extremely user-friendly tools available to them, to make this refinement transpire. Theoretically, more educators will adopt TELEs more readily, as more of the early adopters become more fluent.

Soon, “21st Century Learners” will simply be called “Learners”– as they should be!

References

Edelson, D.C. (2001). Learning-for-use: A framework for the design of technology-supported inquiry activities. Journal of Research in Science Teaching,38(3), 355-385.

Gök, T. (2014). An investigation of students’ performance after peer instruction with stepwise problem-solving strategies. International Journal of Science and Mathematics

Haglund, J., & Jeppsson, F. (2014). Confronting conceptual challenges in thermodynamics by use of self-generated analogies. Science & Education, 23(7), 1505-1529. doi:10.1007/s11191-013-9630-5

Khan, S. (2007). Model-based inquiries in chemistry. Science Education, 91(6), 877-905.

Linn, M., Clark, D., & Slotta, J. (2003). Wise design for knowledge integration. Science Education, 87(4), 517-538.

Spicer, J., & Stratford, J. (2001). Student perceptions of a virtual field trip to replace a real field trip. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 17, 345-354.

Srinivasan, S., Perez, L. C., Palmer,R., Brooks,D., Wilson,K., & Fowler. D. (2006). Reality versus simulation. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 15(2), 137-141.

Vosniadou, S., & Brewer, W. F. (1992). Mental models of the earth: A study of conceptual change in childhood. Cognitive Psychology, 24(4), 535-585. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(92)90018-W

Winn, W. (2003). Learning in artificial environments: Embodiment, embeddedness, and dynamic adaptation. Technology, Instruction, Cognition and Learning, 1(1), 87-114.