Walter Ong’s (1982) ideas on oral cultures and writing are not altogether correct in that they exclude Deaf cultures and their communities. This fault lies in his narrowed view that not “only communication, but thought itself relates in an altogether special way to sound” (Ong, 1982:7). What of the Deaf[i]? Their thought process cannot be linked to sound; their language is not vocal- auditory; it is visual- gestural (Tovar, 2001). Asserting that “[D]espite the richness of gesture, elaborate sign languages are substitutes for speech, and dependent on oral speech systems, even when used by the congenitally deaf ”, demonstrates tremendous ignorance regarding Deaf cultures, their communities and languages. Mexican Sign Language (MSL), for example, is a language in itself, with its own linguistic and social identity and very different from Spanish; the signs are not directly linked to words in Spanish (Faurot et al, 1999). One need not know Spanish in order to learn MSL, or vice versa. What is more, there are some important grammatical differences between Spanish and MSL. “It should be made clear that signed languages are not gestured versions of spoken languages. There is not a one to one mapping of signs to words. In sign languages the “surface forms” of lexical items are mapped directly to real- life referents, not to spoken words”(Faurot et al, 1999: 4). They are not only not universal, they possess important differences specific to their country, region and context that merit further research and their inclusion within the orality-literacy discussion. A critical analysis of some of Ong’s assertions will hopefully demonstrate this.

According to Ong (1982:31), [W]ithout writing words as such have no visual presence, even when the objects they represent are visual. They are sounds. You might ‘call’ them back – ‘recall’ them. But there is nowhere to look for them”. The spoken word or sounds are indeed perishable; as is signed discourse, that if not visually recorded, also perishes unless recalled. However, for the Deaf, sounds do not exist, and the written word is not a written representation of their ‘natural language’[ii]; it is a foreign language. Unlike a hearing person that relates the written words to sounds and then a visual object, the Deaf relate the written word to sound.

It is true that “[W]ritten discourse develops a more elaborate and fixed grammar than oral discourse does because to provide meaning it is more dependent simply upon linguistic structure” (Ong, 1982:38); oral discourse engages the body. In this sense, sign language is similar, but much richer kinesthetically. Some of the uses of the body are: hands as signs used separately or together, but also in relation to the body to denote time, location and aspect; eyebrows and the head may be used for signaling the interrogative, imperative or negative forms, as well as for speech turns; the lips for adverbs of manner or number; the torso and its level of proximity signals register (Josep Jarqer, 2011). According to Janzen (2008 ) the “ three-dimensional spatial component of signed languages … has consequences for clause structure in general, because, it “challenge[s] a more traditional notion of clause structure that depends on a linearly ordered string of lexical items” (Janzen, 2008: 122). Signed language is “encoded in two different perspectives in narrative discourse: static space and mentally rotated space” (Morales et al, 2011:7). Just as “[P]rint situates words in space” and “[W]riting moves words from the sound world to a world of visual space..” (Ong,1982:119), sign language uses space to situate meaning. Like any other human group, the Deaf use sign language to negotiate meaning. Thus, signed discourse in some ways like oral discourse, is less grammatically fixed, but it is much more elaborate.

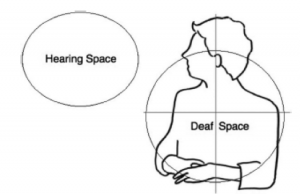

Fig. 1 Deaf vs hearing space [Taken from: Kaneko & Sutton-Spence, 2012:124].

Unfortunately, the limits of this commentary do not allow for a truly thorough analysis of sign language, which throughout this paper has been generalized to contrast its visual-gestural aspect with the vocal-auditory side of oral discourse. However, despite similarities existing between sign languages, as mentioned previously, they are not universal. Just like there are different oral cultures, so is there a Deaf culture made up of smaller Deaf communities each with their own language and culture that cannot and should not be ignored. Ong’s analysis cannot be complete while it ignores this equally important culture.

References

Faurot, K., D. Dellinger, A. Eatough, & S. Parkhurst. (1999). “The identity of Mexican Sign as a Language”. http://www.sil.org/mexico/lenguajes-de-signos/G009i-Identity-MFS.pdf . Retrieved 23/08/12.

Janzen, T. (2008). Perspective shifts in ASL narratives. The problem of clause structure. In: Tyler, Andrea, Kim, Yiyoun, Takada, Mari (Eds.), Language in the Context of Use. Discourse and Cognitive Approaches to Language. De Gruyter, Berlin, pp. 121-144.

Josep Jarque, M. (2011). Lengua y gesto en la modalidad lingüística signada http://www.culturasorda.eu/resources/Jarque_Lengua_gesto_modalidad_linguistica_signada_2011.pdf Retrieved 27/09/12.

Morales-López, E., Reigosa-Varela, C., Bobillo-García, N. (2011). Word Order and Informative Functions (Topic and Focus) in Spanish Signed Language (LSE) Utterances http://www.cultura-sorda.eu/resources/Morales_et_al_WordOrderLSE-2011.pdf Retrieved 29/09/12.

Ong, Walter. (1982.) Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. London: Methuen.

Kaneko, M. & Sutton-Spence, R. ( ). Iconicity and metaphor in sign language poetry. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10926-488.2012.665794

Peluso Crespi, L. (1997). Lengua materna y primera: ¿son teórica y metodológicamente equiparables? . http://www.cultura sorda.eu/resources/Peluso_Lengua_materna_y_primera_1997.pdf Retrieved 27/09/12.

Tovar, L. (2001). La importancia del estudio de las lenguas de señas. http://www.cultura-sorda.eu/resources/Tovar_Importancia_estudio_LS_2001.pdf Retrieved 25/09/12.

[i] Deaf with a capital ‘d’ is used to refer to a people from the Deaf community, while a lower case ‘d’ is used to refer to people with a physical loss of hearing.

[ii] As per Peluso Crespi (1997), who argues that a natural language is one whose medium does not present obstacles to the person using it, should certain physiological characteristics exist.

Thank you for writing on this topic. While reading Ong I had several ideas on the topic but chose to write on other matters. I found your submission comprehensive, informed, and very well done. Thank you.

What a good topic and commentary. I’d never even thought of the deaf or other “fringe” language groups. It’s so easy for those in control of text / technology to forget, ignore, or control other groups (hence my topic, which used First Nations as an example).

Thanks for the informative commentary. I was bothered by Ong’s comment: “[D]espite the richness of gesture, elaborate sign languages are substitutes for speech, and dependent on oral speech systems, even when used by the congenitally deaf ” and you have done such a wonderful job of articulating why/how he was off the mark.