Introduction

Various fictions have experimented with the new digital medium; the vast majority of which are considered avant-garde, experimental, and experiential. This is in art because the reader of fiction must strictly follow the writer’s path (Kress, 2005).

This paper will explore the novel Happenstance, as it pushes the boundaries of its printed medium, shares common traits with other more experimental interactive texts and hyper-fictions, all the while still being accepted by a mainstream readership and blending in as a typical novel. As Bolter (2001) suggests, “Writers seem to need a new concept of structure” (Bolter, 2001, p.152) and Happenstance takes steps towards something new while still paying homage to the old.

A narration typically requires that a single reading path be followed. One does not pick up a text and begin reading fifty pages into the text. If the reader chooses to skip a sentence, paragraph, or chapter they do so at the risk getting lost. There are some exceptions. A collection of short stories may be read in an order other than the order they were printed in; however, the reader is still aware of an intended structure and organization by its printed sequence (Bolter, 2001).

Happenstance

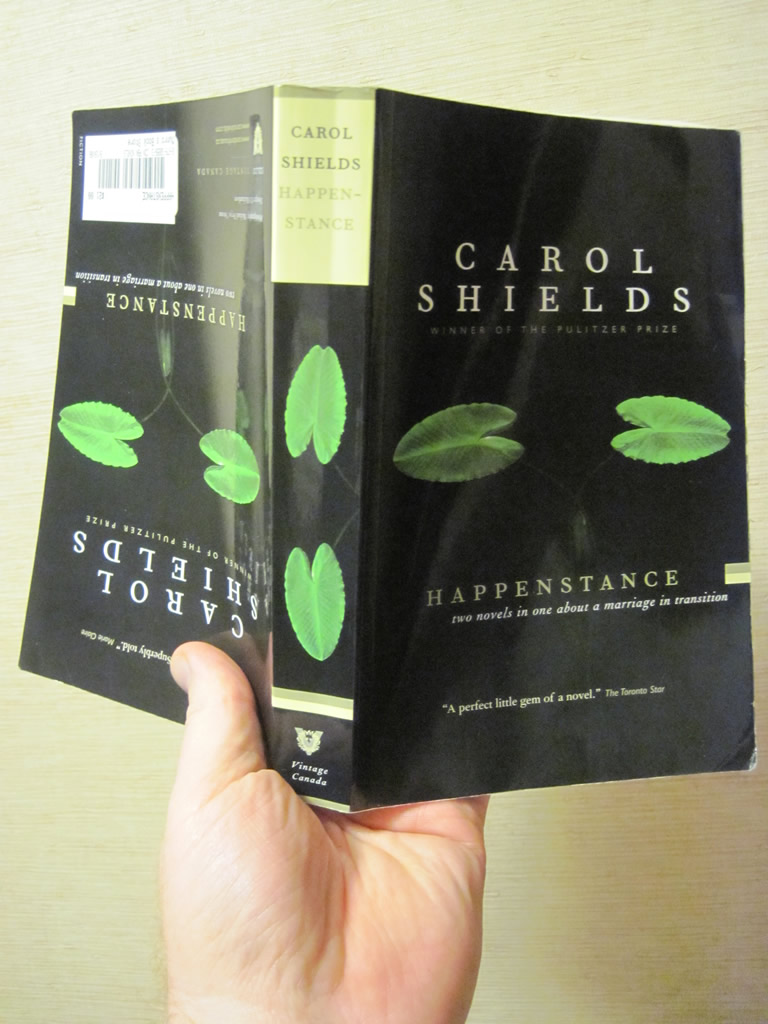

Happenstance,written by well known Pulitzer Prize winning Canadian author Carol Shields, appears to be a typical novel. However, when the book is physically turned over, the back cover is identical to its front.Ignoringthe placement of a barcode and price, it is unclear which side is intended to be the cover. The first few pages of both sides print the same copyright information, reviews, and dedication. The subtitle asserts that Happenstance is ‘two novels in one about a marriage in transition’. Yet, one side begins with the sub-sub-title of ‘The Wife’s Story’ the other begins with ‘The Husband’s Story’.

So the reader is offered several choices. Do they begin with the male or female ‘side’ of the story? How will this choice affect the experience of reading? Will a first impression from one story affect the interpretation of the one to follow? Will they read each to completion, or flip back and forth between the two? In online reviews of the book, readers comment not only on the quality of the text, but also share how they made their choice of which ‘story’ to read first.

The plot of each novel spans a single week where the wife, Brenda, takes her first trip alone to a quilting conference while her husband, Jack, is left to deal with various events which occur at home. Jack’s only friend is going through a divorce and a neighbor attempts suicide. Brenda faces new experiences, feelings of independence, and a chance encounter with a dashing Canadian while at the conference. The couple are apart for the majority of the novel; however, through ever-present flashbacks and recollections employed by the writing style, their stories overlap.

Stream of Consciousness Narration

It was surprising that neither ‘The Wife’s Story’ nor ‘The Husband’s Story’ were written in first person. Instead, both novels employ a third person, stream-of-consciousness style of narration. It is similar in a way to James Joyce’s Ulysses in which events are presented both linear and non-linear. Frequent digressions occur like water, flowing and mimics manner in which consciousness attention tends to wander.

“He often wished he could shut them off, these buzzing thoughts – why was it that he could never do anything, never even think of doing something, without playing at doing it; there was something despicable in his small rehearsals and considered responses; was he the only one in the world who suffered these echos?”(Shields, 1997b, p.155)

This approach allows the author to use ‘these echos’ as a tool to comment on differences between characters in a way that could not be done, had the two novels been written as one. They share a narrative style, yet there is a feeling that differences between the two narrations convey differences in gender.

In ‘The Husband’s Story’, Jack’s mind is far more pre-occupied with actual events, tasks, and matters at hand such as a neighbour’s suicide attempt; whereas, in the opposing story there are relatively more flashbacks and comments upon the experience of traveling on her own for the first time. Furthermore, both novels conclude with their reunion at the airport in different ways. In his story, Jack is physically at the airport looking for Brenda. While in her story, Brenda is rehearsing in her mind the conversation and events she expects upon her arrival. These subtle differences may be highlighting how the masculine is task oriented and the feminine places a greater importance upon feelings and sentiments.

The duality of the two texts seem to parallel a marriage itself. The stream-of-consciousness narration clearly conveys how there is so much to their shared life story together, yet so little said between them. In ‘The Husband’s Story’, Jack comments almost offhandedly about how a room in their home came to be her quilting room. He said that it was because it had good lighting; yet, in ‘The Wife’s Story’ Brenda reflects upon the room in great detail and on multiple occasions. She likes how it overlooks a tree they planted when the first moved into their home. Through her attitudes on the room we come to understand how ownership of that space helped her find purpose at a time when the idea of returning to her secretarial career was an unfulfilling prospect. Another example would be how Brenda is mildly annoyed by the lack of manners and poor attitude of their son, while Jack is thoroughly enraged at his son’s disrespectful insolent behavior. The text embodies the way in which they are both part of a couple and still individuals.

Literary Devices

Novels commonly allude to the future and past. As Bolter (2001) suggests, they encourage flipping mentally or physically to different events. Happenstance is a novel that alters these practices. Depending upon the reading order, literary devices such as foreshadowing become references to the past.

For example, in The Wife’s Story, Brenda asks Jack to buy a pattern for his daughter’s sewing class. She emphasizes how important it is. This is foreshadowing, he does forget; yet, the oversight occurs in The Husband’s Story which covers events at home. If The Husband’s Story is read first, it is his daughter who forgets her pattern. The Wife’s Story reveals he was tasked with this job and it becomes a reference to the past. The truth teasingly lies between the two narrations.

It is also poetic that the stories conclude with the characters being reunited in the physical middle of the book. Shields has been noted to have a fascination with departures and arrivals (Coates, 2008).

As a deft reference to another work that challenged and pushed the boundaries of literature, one character’s suicide attempts follows a poorly received performance of Hamlet. Clearly this is homage to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead. Both stories occur off stage or ‘in the wings’ from one another while events, histories, and characters remain interconnected.

Xandulogical Referencing

On multiple occasions, in both novels, one spouse wonders what the other is doing. The reader is aware that the answer lies in the opposing story and is naturally tempted to switch to the other novel. These interconnections invisibly but clearly link two novels together.

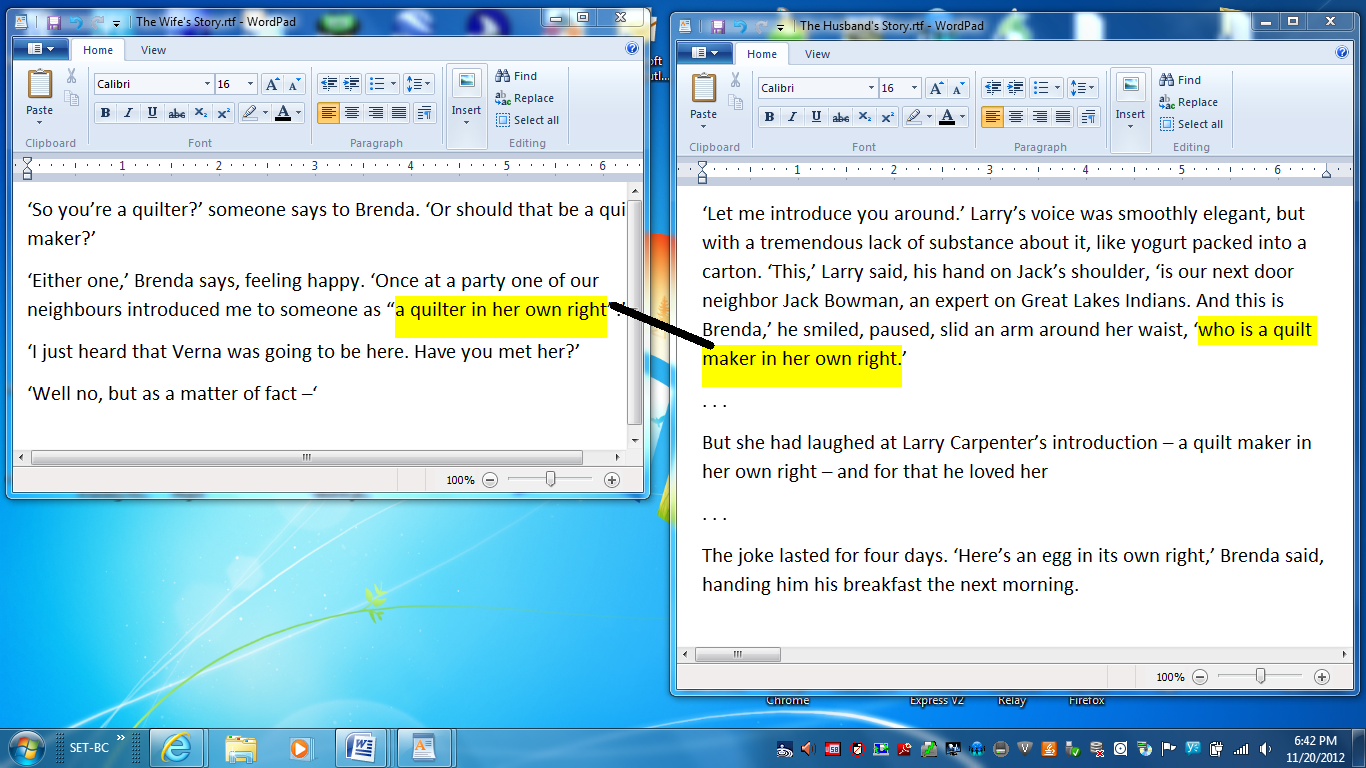

The novel is compatible with other more explicit methods of linking the two stories. Hypertext links could allow the reader to bounce between stories. The novel would also be compatible with ‘transpointing windows’ in a Xandulogical referencing system (Nelson, 1999) as illustrated in the mock up below.

Project Xandu proposed a network be made up of a variety of texts where connecting ideas are visually annotated. However, it has been shown (Dobson & Willinsky, 2009) that reading heavily referenced texts do not really benefit the reader. Instead, it is the process of creating those links that help the reader form knowledge and understanding.

In Happenstance,the reader is capable of subtly making associations while maintaining the feeling of being immersed in the novel; whereas, explicit references or mechanisms used in interactive fictions distract and pull the attention and consciousness of the reader out of the story.

Interactive Fictions

David Bolter defines an interactive text as requiring only two elements “episodes (topics) and decision points (links) between episodes” (Bolter, 2001, p.123). It could be argued that Happenstance qualifies as an interactive text, even though its decision points linking episodes are not explicit or automated. The links are less overt than a hypertext link between the two novels. Still, they are subtle invitations to flip between the two stories. This approach is far more seamless than an explicit link.

Examples of these links include how each character has a different attitudes on a topic or details surrounding each characters’ side of the same story such as how they met. The invitations could not be clearer than when each character, in their solitude, wonder about the other: “Brenda was in Philadelphia; what was she doing at this moment?” (Sheilds, 1997a, p.80) & “What was Jack doing now?” (Shields, 1997b, p.87). The reader is aware that the answer is in the opposing story.

Happenstance is not the only printed fictional text with multiple reading paths. Hopscotch, by Julio Cortazar, offers two possible reading orders. The first is linear, as the text is printed. The second is suggested as an alternative, which creates a fragmented satirical commentary upon the first. Interactivity such as this fractures the linearity upon which narration traditionally relies. A reader expects a story with a beginning, middle, and end. Some earlier examples of anti-linear forms of narration are used by Sterne, Barthes, and German Romantics. They playfully destroy the ‘story’ by abandoning a linear narration or argument. (Bolter, 2001).

In both Happenstance and interactive hypertext fictions such as Victory Garden and afternoon, the author cannot be certain of the path the reader takes. The story is reduced to experiential readings, where “The story itself does and does not end” (Bolter, 2001, p.151). They rejecting the traditional ways of making meaning, they require tremendous mental effort and lack widespread appeal (Ryan, 2005). The effect is esoteric, experimental, and avant-garde. An interactive fiction makes intellectual challenge and experimentation more important than the ‘cozy’ experience that is typically expected from a novel.

They both give up control over order and sequence, yet in Happenstance, the narration maintains suspense and anticipation over what comes next while still giving the reader a comparable level of control. Furthermore, you are certain to get the whole story in Happenstance, while other interactive fictions are expected to have omissions to make each reading unique.

Happenstance pushes boundaries, yet is received not so much as a gimmick but as a commentary on how the couple are together, yet each character still feels alone (Knotch, 2008).

Irony in the Digital Edition

The electronic version of Happenstance is ‘bound’ as a single file, and not two files. ‘The Wife’s Story’ is directly followed by ‘The Husband’s Story’. There is little indication that a choice could be made at all. The second story simply begins following the conclusion of the first. The electronic version ironically encourages only one reading path, while the printed text more freely invites two.

In this case, the eBook medium also offers less flexibility and ease of linking between the two stories. Devices such as the Kobo and Kindle automatically maintain a bookmark as the last page displayed. This further hinders the reader’s interest in flipping between these two stories. Flipping would require manually creating a book mark each time and would hinder the process. Kobo and Kindle offer bookmarks, but only as references that tag text and do not move as the reader progresses through stories. Ultimately, the device expects a novel to have a single reading path and Happenstance is somewhat incompatible with this concept of a novel.

Conclusion

The two novels could have been written as one story, but then it would not have pushed the boundaries of the medium of print we have discussed. The novel could have been printed with one story on all of the left hand pages, and the other story on all the right hand pages; yet, this may have confused the reader and made it closer to other avant-garde works and not blended in. Movies typically follow multiple characters as a director cuts scenes from one scene to the next; in this case the reader is empowered with that choice.

It happens to be that the two stories were individually published in 1980 and 1982; they were only republished in 1999 in the format discussed. Perhaps this knowledge provides some insight as the connections may be directional links originating and conceived from the latter story. Regardless Happenstance happens to be a novel that plays with the medium in a way that still allows it to be accepted as a typical novel while other digital texts have yet to reach audiences in the middle of the spectrum (Ryan, 2005)

Bibliography

Bolter, J. D., (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext and the remediation of print. New York: Routledge.

Coates, Donna . Re Marriage. Canadian Literature, 8 Dec. 2011. Web. 16 Nov. 2012. Retrieved from http://canlit.ca/reviews/re_marriage

Dobson, T. & Willinsky, J. (2009). Digital Literacy. Retrieved from http://pkp.sfu.ca/files/Digital%20Literacy.pdf

Knotch, J.(2008, September 1). Keepin it Real Book Club: Happenstance [Web log message] Retrieved from http://kirbc.wordpress.com/2008/09/01/happenstance-by-carol-shields/

Kress, G. (2005). Gains and losses: New forms of texts, knowledge and learning. Computers and Composition. 22(1), 5-22.

Ryan, M. (2005). Narrative and the Split Condition of Digital Textuality. Retrieved from http://www.dichtung-digital.de/2005/1/Ryan/index.htm

Sheilds, C. (1997a). Happenstance: two novels in one about a marriage in transition: The Wife’s Story. Vintage Canada: Toronto.

Sheilds, C. (1997a). Happenstance: two novels in one about a marriage in transition: The Husband’s Story. Vintage Canada: Toronto.

Nelson, T. (1999). Xanalogical Structure, Needed Now More than Ever: Parallel Documents, Deep Links to Content, Deep Versioning, and Deep Re-Use. ACM Computing Surveys 31(4), December 1999.

Here is a Commentary 3 that touches on storytelling and non-linear narratives.

Another commentary is dedicated to eBooks.

This commentary touches on the senses, and in a way the perception of time is a sense and connects our two posts.

Jerry blended the concepts of an Interactive Fiction with Fan Fiction in his posting here.

Hi Scott,

I liked your detailed run through of interactive fiction. Your use of course readings and the Bolter text was thoughtful and connected. In my own research of interactive fiction, I too noticed that there were differences between print and digital versions.

One last thought before I post my comment. You mentioned the linearity of movies – with director as author – guiding the viewer through the story. In our Rip.Mix.Feed module, I experimented with the idea of interactive videos via Youtube. If you’re interested in viewing it, I’ve offer the link here: https://blogs.ubc.ca/etec540sept12/2012/11/16/a-web-2-0-adventure/.

-Jerry

Scott,

I think your project is fascinating, and I am blown away by the whole thing. How did you come up with the idea to focus on Happenstance? I have been thinking about your comments regarding the ebook version not providing a choice as to where readers begin the story – it seems as if it is cheating readers out of an experience. Even more control will be lost if a film version is created…what would the script look like? Do you think they would try to modify the original version in order to alternate perspectives throughout the story?