If you have spent any time online, you have likely encountered the complaints from older generations about the sweeping cultural changes brought about by Gen Z. Teenagers today are less likely to drink underage, they go out less often, and rates of teenage pregnancy have decreased dramatically. Psychologist Jean Twenge describes this phenomenon as slow living: a lifestyle in which adolescence stretches over a longer period, partly because extended lifespans and shifting social norms have altered societal expectations from young people (268).

A few decades ago, teens counted the days until they could get their driver’s license. Now, it is common to meet adults well past eighteen who still have not obtained one. Parents who were rebellious teenagers themselves have raised their children in far more sheltered environments (Twenge 270). It has become increasingly rare to see kids playing outdoors without supervision or even trick-or-treating freely on Halloween. In an effort to protect children from the dangers of the outside world, parents prefer to keep their kids where they can see them. Compared to parents of the past who limited screen access, many of today’s parents allow near-unrestricted device use. Children now often receive an iPad long before they get their first bike—that is if they get one at all.

As a result, children’s perceptions of the world are now doubly mediated: first by their parents, and second by digital devices. One could argue that parental supervision is not new and that all children come to understand the world through some form of adult mediation. But in the past, these restrictions created fertile ground for rebellion and experimentation (Twenge 270). Twenge cites an article explaining how “the internet has made it so easy to gratify basic social and sexual needs that there’s far less incentive to go out into the ‘meatworld’ and chase those things… The internet [can] supply you with just enough satisfaction to placate those imperatives” (267) There is no more need for transgression because all desires can be fulfilled through digital mediation.

This is congruent with Alison Landsberg’s concept of prosthetic memory. These are memories that are not imprints of any personal experience but rather, are implanted in a person’s consciousness, typically through mass media (Landsberg 175). She used the example of cinema, but in an age when people are bombarded with digital images every waking minute of the day, it is safe to assume that most of their senses have been thoroughly numbed. Many of their lived experiences have been replaced by prosthetic memories which have so completely embedded themselves into their lives that it is hard to discern the difference between the real and prosthetic. With unrestricted access to the internet, the boundary between childhood and adulthood blurs. Children regularly encounter media created for adults including everything from movies, television, to social platforms. Inevitably, these cultural products contain adult themes with often little to no restrictions on who gets to access them. The result is an early desensitization that is in line with Baudrillard’s claim that postmodern society is marked by the disappearance of “real” experience (178).

But if digital experiences are replacing ‘real’ ones, does that mean younger generations are not living at all?

Well, not exactly.

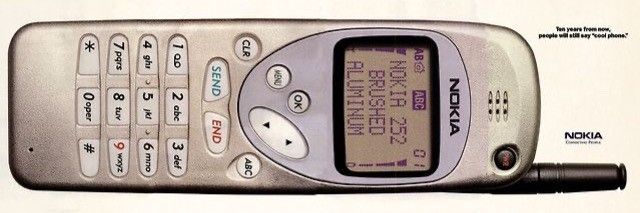

Landsberg argues that mediated experiences can be crucial sites of identity formation. Prosthetic memories function as stand-ins for lived experience. Theis ability to shape our identities is almost identical to that of real experience (Landsberg 180). This is especially visible in the aesthetics popular among Gen Z. Many of today’s popular trends, from 80s revivals to the y2k renaissance, are rooted in nostalgia for eras most Gen Z members never experienced firsthand. Yet these revivals are not always faithful recreations. For instance, the term y2k originally referred to the Year 2000 computer bug and the anxieties surrounding it, but in the 2020s it has come to signify the most glamorous, desirable aspects of early-2000s pop culture. For Gen Z, y2k has taken on an entirely new meaning. Landberg claims that as social creatures, humans are eager to position themselves within narratives of history. Despite not having lived through the era themselves, through the prosthetic memories obtained from media representations of the 90s and 2000s, Gen Z extracted key elements of the style prevalent in those periods to revive and reconstruct y2k into an aesthetic unique to the 2020s.

Landsberg maintains that the line between real and mediated experience is not etched in stone. All experiences are mediated experiences, and to consider digitally mediated experience to be lesser than ‘real’ experience is quite a narrow point of view (Landsber 178). As Marshall McLuhan famously said, “All media works us over completely.” Thus, from a Landsbergian point of view, the fact that most of Gen Z’s experiences are digitally mediated, does not mean that they are not really living.

However, despite Landsberg’s technological optimism, I am a bit hesitant about fully embracing mediated experiences. My opinions align more with Baudrillard’s theory of hyperreality (Landsberg 178). Though I agree that most experiences are mediated, I also do believe the physical materiality of lived experiences is superior to digitally mediated experience. Ultimately, no matter how pervasive digital technologies become, I believe we should try to engage in ‘real’ experiences alongside digitally mediated experiences as much as we can.

references

- Cari | Aesthetic | Y2K Aesthetic. Accessed December 2, 2025. https://cari.institute/aesthetics/y2k-aesthetic.

- Landsberg, Alison. “Prosthetic Memory: Total Recall and Blade Runner.” Cyberspace/Cyberbodies/Cyberpunk: Cultures of Technological Embodiment, 1995, 175–90. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446250198.n10.

- Twenge, Jean M.. Generations : The Real Differences Between Gen Z, Millennials, Gen X, Boomers, and Silents–And What They Mean for America’s Future, Atria Books, 2023. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ubc/detail.action?docID=7208544. 177-249

This is a super cool read. There’s a theory in human geography called active-space, referring to the topographical area in which one lives there life and has their active world. When your a kid, your active area is very small and, as you age into adolescence, it starts to expand rapidly. The actual extent in which one develops into depends upon so many factors: access to education, transportation, financial resources etc. It’d be interesting to see some of the phenomena that you discuss in this post (in regards to digital mediation of spatial relationships) and contextualize the specific effects of certain media technology as a more pronounced actor within the Human-geo discipline’s discourse active space.

I agree with your take about the physical materiality of lived experiences being superior to digitally mediated experiences, but I fear that in this modern age the two are inexplicably intertwined. For example, when hanging out with my friends, more often than not a device is present, and our interaction is mediated by the device. Watching a movie together on the TV, playing a video game together, scrolling through reels on our phones while talking to each other, etc. This relates back to Turkle’s argument about how we are always alone together–living in our internal worlds within our devices while being externally with other people. How then is that materiality weighted?

I completely agree with you. I don’t think a reality completely divorced from material reality is realistic, but I would still like to work towards some conception of ‘real’. In an age where most of our activities and communication is faciliated through digital means, I think just being present in the same space as people would count as a material experience for me. So in answer to your question, I think materiality (at least for me) can be weighed in terms of spatiality.

I thought the connection between Gen Z’s screen habits to Landsberg’s concept of prosthetic memory was very smart. Your discussion of how aesthetics like y2k are revived through digitally mediated memories, shows that these experiences aren’t meaningless, they still contribute to identity formation, even if they weren’t lived firsthand. I also agree with your caution about privileging real, physical experiences alongside digital ones. It’s a helpful reminder not to let screens completely replace engagement with the world. And this leads me to ask, if there is any way we can ensure that Gen Z balances prosthetic memories with experiences that are fully “real” in a tangible sense?

I think many people are now having the growing realization that being overly dependent on our screens can be detrimental. It is a good start towards building that balance that you speak of, but as much as I would like to, I think it is really hard to actually achieve it. These prosthetic experiences have embedded themselves into our society so thoroughly, that to deconstruct the sytem of things as it is currently would require us to peel back several layers of technological mediation. Ultimately, a certain level of digital mediation will always be present even in the most ‘real’ and tangible interactions but I personally would like to work towards the conception of that ‘prelapsarian’ moment Landsberg derides, no matter how unrealistic or foolish it might be.

I love how you connect Twenge’s “slow living” argument with Landsberg and Baudrillard to show how childhood today is mediated twice over: first through parental caution, and then through digital interfaces. Your point about rebellion disappearing because the internet already satisfies so many impulses really landed for me. It reframes “kids staying home” not as laziness, but as a structural shift in how desire gets managed.I also appreciated your point about Gen Z nostalgia as a form of prosthetic memory. It’s such a clear example of how media lets people “remember” eras they never lived through while still feeling personally connected to them. And you’re right to question Landsberg’s total optimism, Baudrillard’s hyperreality feels uncomfortably relevant when everything can be simulated so smoothly that experience itself starts to blur.

That last line makes me think of generative AI, and how Landsberg’s concept of prosthesis of memory could be applied in this case. It’s one thing for mediated images to imprint themselves onto your memory, but what happens when those images themselves are derivative and not representative of any real experience? As we have already seen the dangerous implications of AI generated images, I would like to err on the side of caution and try to engage in ‘real’ experiences as much as I can.