In the second-to-last chapter of Tim Ingold’s Making: Anthropology, Archeology, Art and Architecture, Ingold centres around the idea of ‘the hand’ and brings up philosopher Michael Polanyi in his opening statements to highlight ideas of ‘telling’, ‘articulating’, and ‘knowing’. Ingold believes that while everything can be told, not everything can be articulated, and to strengthen his argument he uses one of Polanyi’s notable pieces of work, the book The tacit dimension, as a framework for what Ingold believes about knowledge and how it is communicated.

Background on Michael Polanyi and his work

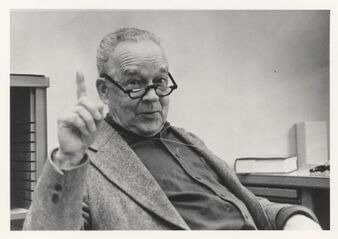

Michael Polanyi was a physicist, chemist, and philosopher who was born in 1891 and passed away in 1976. He lived through both world wars, even migrating from Germany when Nazis took power (The Polanyi Society), and his philosophical work that he developed later in life was heavily influenced by living through those global events, being introduced to philosophy via Soviet ideology under Stalin (Polanyi 3). The book that Ingold refers to, The Tacit Dimension, was originally published in 1966 and introduces Polanyi’s idea of “we know more than we can tell” (Polanyi 4).

Formal vs. Personal Knowledge

Polanyi’s view on thinking and knowledge was that ‘we know more than we can tell’ (Polanyi 4) and he classified knowledge into two camps: personal and formal. Formal knowledge is knowledge that can be specifically articulated and explained clearly to someone else, whereas personal knowledge cannot. Personal knowledge, to Polanyi, is the type of ‘know-how’ that only comes from the experience and practice that an individual goes through, whether it be perfecting a craft or learning how to hunt, which he also described as tacit knowing (Polanyi 20). It is not able to be articulated and thus, it cannot be taught. Ingold very much disagrees with Polanyi’s sentiment about personal knowledge being ‘untellable’ and argues, for example, that the idea that the age-old example of a craftsman being suddenly unable to explain how they do what they do when asked, is unfounded (Ingold 109). Ingold argues that people are absolutely able to communicate and “tell” others what they do, no matter how innate or personal it may seem. However the telling is not necessarily verbal, but it can be shown and demonstrated. This ties into Ingold’s belief that people correspond with the world and think through making. Polanyi’s perspective doesn’t make sense through Ingold’s lens, because if unspoken stuff or lessons couldn’t be taught since they were ‘personal’, then no one could learn through making, and learning through doing is a well-established fact of life. Polanyi’s view on knowing is also a bit confusing, as when he describes it in detail when describing an experiment involving a frog, he seems to assume that knowing what a frog is and knowing to do an experiment is tacit knowledge (Polanyi 21), despite the fact that a frog very much can be taught about. The ‘otherness’ of a frog might be innately human and ‘tacit’, but to suggest that that cannot be described makes me agree with Ingold.

Ways of Telling

To further help prove his point, Ingold in this chapter highlights the different forms of ‘telling’ to both debunk Polanyi’s ideas, and set up Ingold’s overall argument, which is that everything can be ‘told’. Ingold talks about storytelling, which is a form of telling where a narrative is told that includes lessons and patterns, and then there is ‘telling’, which is the more discernible approach where people search for ‘tells’ in others. For example, studying someone’s face while playing poker is a ‘tell’, since you are using environmental clues such as the furrowing of their brow and the tapping of their fingers on the table to make a judgement for yourself about what is really going on. Ingold brings up an example of being able to tell the tone in which a handwritten note was meant (or not meant) to be received, based on the inflection marks on the letters (Ingold 110). These two methods of telling come together in storytelling as well, but if Polanyi’s method of thinking on ‘tells’ were accurate, Ingold states that that would mean all stories would have the same exact meanings or lessons because of how rigid Polanyi’s ‘formal’ and ‘personal’ knowledge perspective functions. Stories do not work that way though, as they are purposely told with a degree of open-endedness so that the audience can bring about their own meaning and takeaways from it. As an example, Little Red Riding Hood is a classic tale that, in effect, teaches children about stranger danger. The story does not set out to literally warn children of actual wolves that can eat one’s grandparent, but it is close enough to a real example of a wolf being a shady stranger that readers can figure out the lessons behind the words. For Ingold, the lessons that stories give are less of an ‘answer’ and more of a path or trail that one can follow (Ingold 110), and from there everyone gets something unique out of it.

Ways of Thinking

To close out his argument regarding Polanyi’s words specifically, Ingold talks about ‘articulate thinking’, which is the process of thinking about one’s words before speaking them, organizing them in the brain all in advance before sharing the thoughts with anyone else. He argues that if every time people thought it were ‘articulated’, no thinking or ‘making’ would happen because everything would have to be thought of in advance, which goes against the learning-through-doing that Ingold has mentioned in the past. While Polanyi sees the ideas of formal and personal thinking as an iceberg nearly completely submerged in water, with only the formal tip of the ice peeking out of the water (Ingold 109), Ingold sees it as a series of islands that water flows freely around, knowledge being a mix of the two (Ingold 111), instead of a cut-and-dry one or the other. Ingold highlights the fact that in Chapter 1 of Making, he also talks about the idea of ‘knowing’ and ‘telling’ being the same thing, and he argues now that Polanyi is wrong because to know is to tell (Ingold 111), and so to suggest that people possess knowledge that cannot be conveyed is preposterous. Once again, this is not to say that everything ‘told’ will be in a neat verbal package, but rather that everything a person does is telling something in some way. So while not every scholar can articulate their knowledge, they can all tell it (Ingold 111).

Polanyi in The tacit dimension draws upon Plato’s theories to try and explain how someone can’t search for an answer (if they know what to look for they’re fine, and if they don’t know what to look for then they don’t know) as support for Polanyi’s arguments about how knowledge cannot be ‘explicit’ (Polanyi 22). This is an interesting perspective that Ingold does not write about, since if you break it down you can find a sort of through-line for all knowledge, like how you go to school to learn, ask teachers questions for more information, and so on. Despite this, it still does not address Polanyi’s flawed claim that personal knowledge cannot be taught, giving Ingold the more compelling argument.

In short, Ingold uses Polanyi’s ideas on ‘telling’ and ‘personal knowledge’ to highlight how his own perspective is correct, because to know is to tell, and even if it’s something as simple as a mechanic tuning up a car or a person knitting a sweater, even without step-by-step instructions they are wholly able to tell what they are doing to others.

Works Cited

Ingold, Tim. Making: Anthropology, Archeology, Art and Architecture. 1st ed., Routledge, 2013, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203559055. Accessed 4 December 2025.

Polanyi, Michael. The tacit dimension. Edited by Internet Archive, Gloucester, MA, 1983. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/tacitdimension0000pola/page/4/mode/2up. Accessed 4 December 2025.

The Polanyi Society. “Michael Polanyi.” The Polanyi Society, https://polanyisociety.org/michael-polanyi/. Accessed 28 October 2025.