Shaping the World & Letting It Shape Us

In the Making

Oftentimes, we may think that making starts with an idea in our head that turns into a physical form in the real world. However, every time we make something, sketch an idea, or fix something broken, we are also learning along the way. Tim Ingold’s Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture (2013) reconsiders what it means to create. Instead of viewing the act of making as simply turning concepts into objects, Ingold describes it as a process of growth and interaction with materials. Amongst many theorists and scholars, his thinking builds on the psychologist James Jerome Gibson, who argued that we experience the world through an “education of attention,” gaining knowledge by simply noticing the environment around us. As we live and learn amid the world around us, we continuously pick up creativity through exploring and responding to the interactions that shape our experiences.

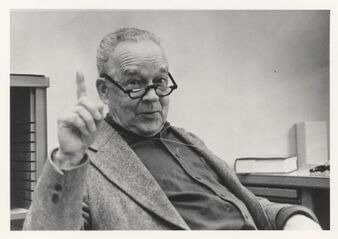

About James Jerome Gibson

James Jerome Gibson was an American psychologist known for his influence in the field of ecological psychology, the study of the relationship between organisms and their environments, where an organism’s behaviour is shaped by “affordances”. Born in McConnelsville, Ohio, in 1904, Gibson earned his Ph.D. in psychology from Princeton University in 1928 then taught at Smith College and Cornell University, where he began his pioneering research.

https://monoskop.org/James_J._Gibson

Gibson explains in his most influential work, The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception (1979), that affordances are the possibilities for specific actions that the environment provides and the perceiver’s abilities. (Gibson 119). For instance, how a chair invites us to sit and a path invites us to walk on it .

Gibson’s theory rejects the notion that the mind and body are independent from one another and emphasizes that our perception and actions work hand in hand to understand our world through our bodies as we move and interact with it. This is what Gibson refers to as the “education of attention,” which is the process of learning by noticing information through participating experience and movement, rather than by solely passive observation (Ingold 2).

The Art of Paying Attention

Ingold draws from James Gibson’s concept of the education of attention to explain how people learn by doing. Through every move we make in our bodies, we learn to perceive by being active participants in our environment. Ingold draws Gibson’s concept of the education of attention to argue that making works the same way, as the maker learns through attentive participation while being attentive to materials, developing sensitivity to their textures, resistance, and potential.

In Making, Ingold writes that learning occurs through “what the ecological psychologist James Gibson calls an education of attention” (Ingold 3). The maker learns by feeling, sensing, and responding to the materials, not just by following a set plan in their head. Ingold also says that we “learn by doing, in the course of carrying out the tasks of life” (Ingold, 13), explaining that creativity is an ongoing journey between the maker, their bdy, and then the materials that they interact with.

Affordance in Materials

Ingold provides an example in chapter 3 of Making, “On Making a Handaxe”. Ingold describes the Acheulean handaxe, which was made from flint over more than a million years ago. The origin of this axe came about when knappers paid attention to how the stone reacted when struck, noticing how the sharp edge and shape of the axe formed naturally (Ingold 34–38). This example proves that Ingold extends this idea into materials themselves when making, where they also “join forces” in possibilities for action (Ingold 21). For example, clay affords shaping, wood affords carving, and yarn affords knitting. Thus, the maker’s creative process is shaped by both their intention and by the affordances that materials and tools display through use.

“I want to think of making, instead, as a process of growth. This is to place the maker from the outset as a participant in amongst a world of active materials. These materials are what he has to work with, and in the process of making he ‘joins forces’ with them, bringing them together or splitting them apart, synthesising and distilling, in anticipation of what might emerge.” (Ingold 21)

Ingold’s approach to affordances indicates that materials and textures are not just passive tools because they indirectly participate in the creative process. Our duty is to respond to these affordances through attention so that making becomes a partnership between us and the world, rather than a one-sided action of control by humans.

Applying Gibson and Ingold to Our Media Environment

In terms of media studies, Gibson’s theory about affordances as well as the notion of “education of attention,” are relevant. Though Gibson’s ideas are connected to ecological affordances, we can use them to discuss media landscapes and what they provide us with. Ingold and Gibson’s theories surrounding anthropology, ecology, and psychology, when translated to understanding digital media, provide valuable insight about how we interact with, and use technology.

A current example of Ingold’s application of Gibson’s theory can be seen in our digital habits, where we feel confused and overwhelmed with the features of emerging technologies. However, through continuous engagement, experimenting with new technological tools rather than repressing them, we slowly develop a system’s flow. Understanding the environment remains relevant now, beyond building axes and houses, as we are now experiencing a new type of environment, the media environment. Our perception and creative abilities evolve faster as media itself becomes a space of exploration between human attention and technological affordance.

By drawing on Gibson’s concept of “the education of attention,” Ingold shows that learning, creating, and perceiving all arrive from active engagement and participation with the environment. Though Gibson was mentioned only once throughout the entire book, the concept of the education of attention helps lay the groundwork for his later arguments on correspondence and material growth, where Ingold explains that perception, movement, and creation are all essential and related processes. Hereafter, making is a way of paying closer attention to the environment and being in touch with the world as it takes shape through our hands.

Contributors:

Kenisha Sukhwal, Aubrey Ventura

References:

Gibson, James J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Houghton Mifflin, 1979.

Ingold, Tim. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. Routledge, 2013.

“James J. Gibson.” Monoskop, https://monoskop.org/James_J._Gibson. Accessed 18 Oct. 2025.

Hi Kenisha and Aubrey! This was a really great post, and I enjoyed learning more about Gibson’s academic work! Reading about Gibson’s education of attention reminded me a lot of Andre Leroy-Gourhan’s graphism theory and his discussion on how mind and body and hand and language are inherently intertwined, found in the Critical Terms chapter 21 Writing (something that Ingold actually references later in Making). It is interesting to see how different texts have included these similar concepts in their arguments, as it connects writing to making as a dynamic process.