How should we define authenticity? As humans grow more attached to digital media, the distinction between the virtual world and authentic, “real life” grows convoluted. Alison Landsberg’s chapter, “Prosthetic Memory: Total Recall and Blade Runner”, demonstrates the tendency of viewers to adopt emotional movie scenes as authentic memories of their own. In “The iPhone Erfahrung: Siri, the Auditory Unconscious, and Walter Benjamin’s ‘Aura’”, Emily McArthur demonstrates how Siri, a voice-activated personal assistant, situates users in seemingly authentic human power dynamics. Both Landsberg and McArthur emphasize the “posthuman” nature of our modern world where memories and identities, manufactured by media, become injected into our bodies. Together, their texts question whether mediated memories and identities can be deemed authentic.

Landsberg believes authentic human representation exists in mediated memory. Unlike Baudrillard who believes modern society is divorced from the “‘real’” and entrapped in “a world of simulation” (qtd. in Landsberg 178), Landsberg argues such a distinction never existed in the first place since “information cultures” and “narrative” have always mediated “real”, lived experience (178). She expands her belief by discussing how movie scenes can feel just as real as lived memories. Like Walter Benjamin and Siegfried Kracauer, she emphasizes cinema’s ability to produce societal change and “political” collectivism (181). During a moving cinematic experience, audience members may identify with characters and their on-screen adversities; as a result, Landsberg notes films hold “potential to alter one’s actions in the future” (179-180). To Landsberg, movie scenes are not mere fragments of mass media, but “prosthetic memories” which audiences adopt as their own. Unlike natural memories–experienced individually and firsthand–prosthetic memories are acquired virtually, without truly experiencing them (180). Nevertheless, like all memories, prosthetic memories construct identity and how we empathize with others (176).

As suggested in the title of her text, Landsberg explores the portrayal of prosthetic memories in popular dystopian films such as Total Recall and Blade Runner. In Total Recall, the protagonist, Quade, discovers his life has been manufactured by “the Agency” (Landsberg 181). As a result, he recollects a past he has not experienced; his life has been constructed of injected memories, raising the “question of his identity” (181). His privileging of these memories over his natural self is especially prominent when he is unable to recognize “his face on a portable video screen” (181-182); he associates his authentic self with his prosthetic memories, rather than his facial features, posing the question of whether Quade’s implanted memories are more authentic than his own human body (182). Blade Runner similarly investigates the difference between authentic and inauthentic memory. Rachel, the love interest to Deckard, the film’s protagonist, is an enslaved humanlike robot known as a “replicant”; her memories are manufactured by her employer, Mr. Tyrell, who ensures control over replicants by manipulating their pasts (Landsberg 177). When Rachel plays the piano for Deckard, she states she “‘remember[s] lessons’”; here, Deckard ignores her fabricated past (185). She plays “beautifully” regardless of whether her lessons were prosthetic or “‘real’”, posing the question of whether lived, self-produced memories are better than prosthetic ones (185). To Rachel, her memories of these lessons are real, authentic, and personal even though they are manufactured. Altogether, Landsberg interprets the film as a demonstration that memories, regardless if they are prosthetic or lived, construct meaningful, seemingly authentic identities. Like Total Recall, Blade Runner obscures our distinction between inauthentic, manufactured memories and real, lived experience.

While Landsberg merges the worlds of prosthetic and authentic memory, McArthur blurs the distinction between machine and human by discussing Siri, a virtual voice-activated assistant. McArthur defines Siri as a “natural language processor” (NLP), a machine that communicates with users through “human language” (116). She notes that “language ability” is typically defined as the factor that “‘makes us human’”; however, digital programs like Siri who produce human speech subvert this notion (116). She notes that Siri produces a humanlike voice through invisible processes of “translation and synthesis” (117). She can be similarized to a being, rather than a set of machinic parts, since a user only hears Siri’s personalized speech that uses “colloquial language” and addresses the user by their name (117). While a traditional Google search produces innumerous results, Siri replicates authentic human communication by providing a singular response to its user’s inquiry (117). In addition to prosthetic memories, Siri’s computer-engineered, anthropomorphic state obscures the difference between inauthentic and authentic.

Overall, Landsberg and McArthur demonstrate the ability of media to construct identity. Landsberg demonstrates how prosthetic memory defines “personhood and identity” by citing Herbert Blumer’s studies of young adult reactions to films (187, 179). In his studies, Blumer found several respondents practiced “‘imaginative identification’”–the unconscious projection of “‘oneself into the role of hero or heroine’” (qtd. in Landsberg 179). Landsberg illustrates “imaginative identification” as especially impactful; she emphasizes that one respondent who adopted the identity of The Sheik’s “‘heroine’” even felt the kisses of a fictional love interest (Blumer qtd. in 179). Conversely, McArthur demonstrates how NLPs like Siri produce “social hierarchies ” in addition to identity (116). She notes Siri imitates classist and gendered human dynamics by resembling a “‘personal assistant’” who answers to the wishes of her user (119). Additionally, Siri’s effeminate voice accentuates her “secretarial” tone; by acting as an assistant, her user adopts the identity of a master (119, 120). Furthermore, the user, regardless of their class, becomes a “bourgeois subject” by gaining an immediate “sense of power” over Siri (119). In combination, Landsberg and McArthur demonstrate how media and technology form authentic human identities.

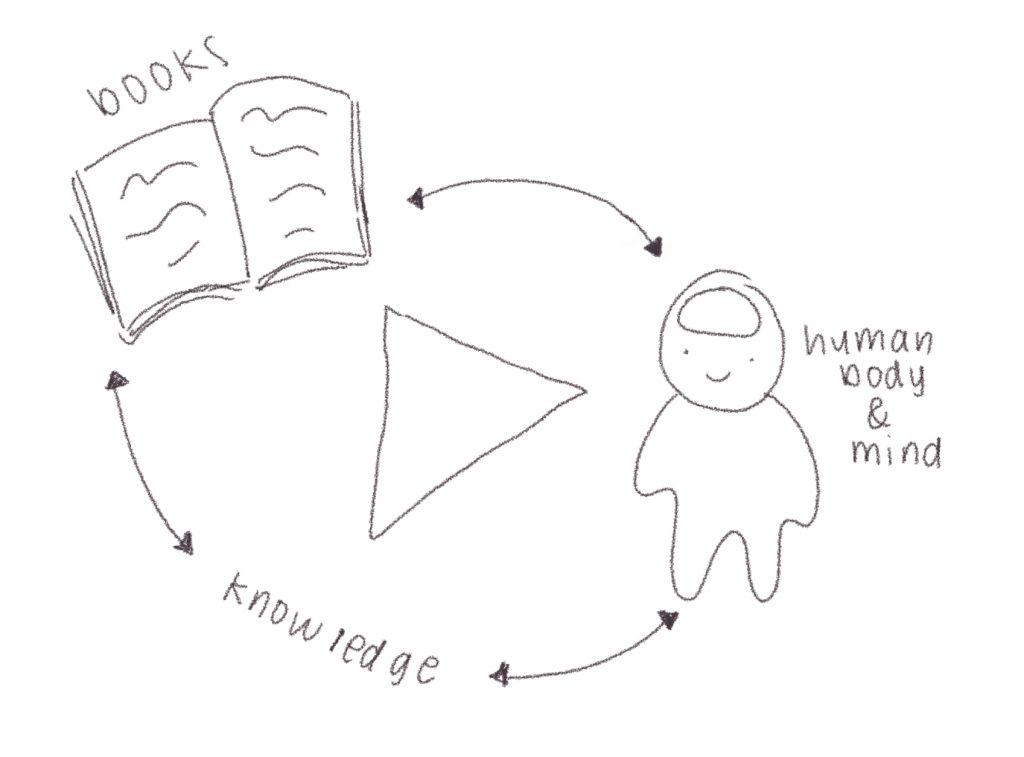

Prosthetic memory and NLPs are also theorized to produce authentic bodily effects. For example, Landsberg mentions the “Payne Studies” which aimed to calculate the ability of film to physically affect “the bodies of its spectators” (180). Observations of spectators’ “electrical impulses”, “‘circulatory system[s]’”, “respiratory pulse and blood pressure” revealed the potential of film to cause “physiological symptoms” (180). This hypothesis aligns with “‘innervation’”, a Benjaminian view that “bodily experience” and “the publicity of the cinema” can generate collective social movements (Landsberg 181). While films potentially induce diverse biological responses, NLPs like Siri, transform the human body’s processing of sound. McArthur notes humans unknowingly “tune out” noises, transferring them to their “unconscious”; she equates this instinct to seeing “‘without hearing’” (Simmel qtd. in 121). Siri, a “disembodied technological voice”, however, forces users to hear “‘without seeing’”; her lack of physical form forces users to rely on different senses (122). As a result, prosthetic memory and NLPs alike produce authentic, corporeal effects.

In our lectures and tutorials, we have often discussed media’s establishment of body standards, virtual identities in video games, and avatars on dating sites; this comparison of texts expands this discussion by showing a melding of virtual and “real” life through film and NLPs. The authentic and anthropomorphic qualities of new media demonstrate that the “posthuman” era is not a faraway prediction embedded in dystopian futures; rather, it is situated in our present. Modern reliance on media as a guide for identity formation is prominent in our adoption of cinematic prosthetic memory and our widespread use of humanlike NLPs. While Landsberg demonstrates films’ abilities to implant prosthetic memory and construct identity, McArthur demonstrates natural language processors’ abilities to construct identity by placing users in power dynamics. The impact of prosthetic memory and natural language processors can also be perceived through their corporeal effects. Altogether, these powerful forms of media entangle the concepts of inauthentic and authentic.

Works Cited

McArthur, Emily. “The iPhone Erfahrung Siri, the Auditory Unconscious, and Walter Benjamin’s ‘Aura’.” Design, Mediation, and the Posthuman, edited by Dennis M. Weiss, Amy D. Propen, and Colby Emmerson Reid, ch. 6, Bloomsbury Publishing, 14 Aug. 2014, pp. 113-127.

Landsberg, Alison. “Prosthetic Memory: Total Recall and Blade Runner.” Cyberspace/Cyberbodies/Cyberpunk: Cultures of Technological Embodiment, edited by Mike Featherstone and Roger Burrows, SAGE Publications, 1995, pp. 175-189.

Photo Credit

Yap, Jeremy. turned on projector. Unsplash, 9 Nov. 2016, https://unsplash.com/photos/turned-on-projector-J39X2xX_8CQ.

Written by Emily Shin