Introduction

Even though everyone has come to realize that internet has always been a medium of chaos and conflict, but it has always been mildly confusing for us that while verbal sparring in reality is a relatively mild and civilized form of exchanging viewpoints, online it becomes a genuine battlefield—strangers clash fiercely over differing opinions, or sometimes simply to provoke, with conflicts erupting openly for all to see. I’ve also seen many ordinary content creators who share their daily lives eventually forced to turn off private messages after gaining attention, because clearly, many people use such channels like random assailants, aiming only to wound without reason.

If aliens studying Earth were to witness the spectacle of online discourse, they might be astounded by the stark contrast with the polite and respectful demeanor most people display in real life. What causes such a clear divide in behavior between the online and offline worlds for the same individuals? Does the digital environment inherently make people more irritable, less tolerant, and unwilling to understand others? In this article, we will explore this very question—specifically, the causes of environmental polarization and the role the media plays in it.

Network Polarization and the Online Environment

Network polarization refers to the phenomenon where issues that might be understandable in real life are continuously amplified and fixated upon by online communities to the point of harsh criticism. People become less tolerant of differing viewpoints online, while growing increasingly exclusive within their own labeled groups—even if their so-called “allies” might struggle to hold a two-sentence conversation with them in real life. Environmental polarization makes everyone more sensitive and defensive. In this climate of pervasive insecurity, individuals seek solace in groups, yet this very process only deepens the divides between people. While cooperation and understanding thrive offline, online, certain opinions are immediately branded as heresy worthy of burning at the stake—judged with absolute, uncompromising harshness.

If we look back at the online environment around 2000, although media technology was far less efficient and accessible than today, the atmosphere of communication was generally much healthier than the current state, where a single comment can rapidly poison a community. Does this mean the advancement of media technology is not truly a positive development? Perhaps, as Umberto Eco wrote in Chronicles of a Liquid Society (2017), “Progress doesn’t necessarily involve going forward at all costs.” While Eco was mainly discussing the unnecessary “diversification” of physical inventions that replace what already exists, I suspect he would also disapprove of today’s digital landscape.

Potential Reasons Behind Network Polarization and the Influence of Media

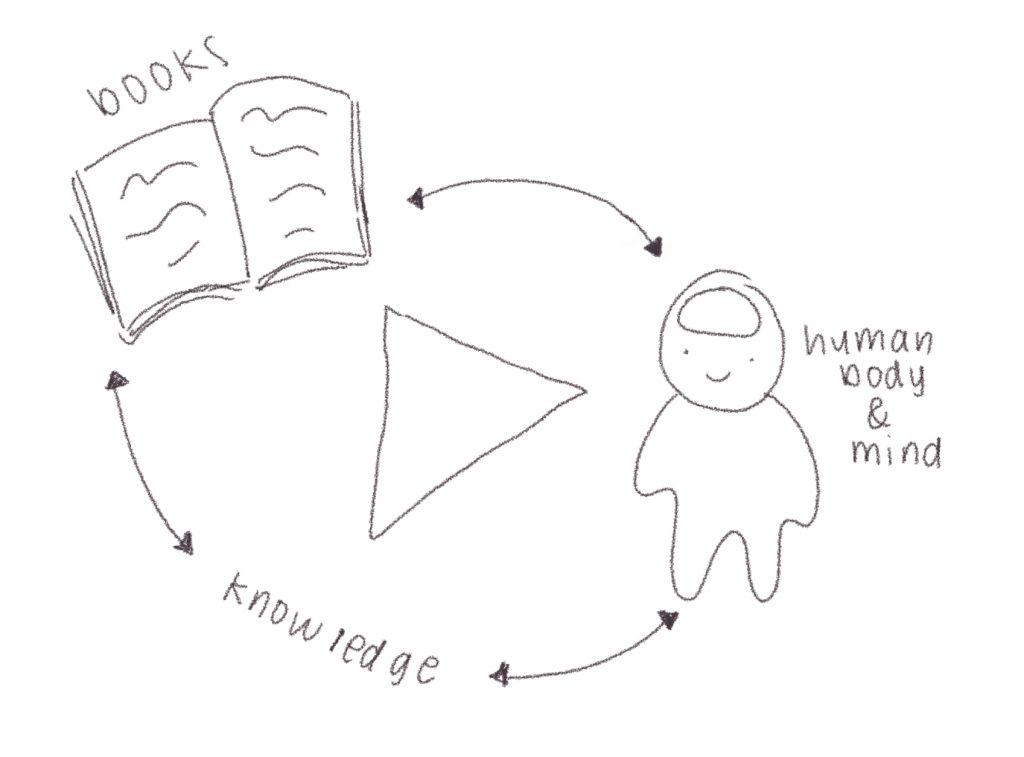

To understand why online environments intensify conflict, we can turn to Gibson’s ecological perspective, which helps explain why digital environments intensify conflict and relies on what the environment makes available to us. Applied to online usage, this suggests that when people use social and online platforms, they shape the exact platform they are using while the platform itself simultaneously shapes them.

In The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception, Gibson emphasizes that the “animal and the environment make an inseparable pair” (p. 8). Gibson writes that the perceiver is always surrounded by “the medium in which animals can move about (and in which objects can be moved about) is at the same time the medium for light, sound, and odor coming from sources in the environment.” (p. 13), meaning that perception is shaped by whatever information the environment supplies.

One major factor of polarization is selective perception. Our online feeds are not a neutral environment, as algorithms curate and amplify content that they assume the user appears to be “looking for.” This makes polarization feel natural and unavoidable because the environment reinforces the observer. Online, this means users often search for confirmation validation that aligns with existing emotions and beliefs.

Gibson also reminds us that perception is active, not passive. He states, “we must perceive in order to move, but we must also move in order to perceive. ” (p. 213). Online, there is constant “movement” in scrolling, liking, and reposting, which affects what the users perceive next based on the algorithm. The environment is always refreshing, adjusting to user behaviour. This repeated cycle then boosts reactions and reinforces patterns, making it easier for polarization to become a way of interacting.

Looking into Media: a Tool or an Amplifier?

Concluding from Gibson, we can say that the internet we are looking into is not a neutral environment, and media does not only act as a tool for our voices. Depending on algorithms, the pages shown to everyone are different, designed for our own taste. By manipulating what people perceive, media and the internet can easily influence the opinions of people, and the information cocoon will naturally feed towards the minds of the opinions already there, making the opinions increasingly polarized and entrenched. People use the internet to voice themselves, but the internet will also amplify what they are saying to other people’s ears.

Sources:

Eco, Umberto. “Have we really invented so much?”. Chronicles of a Liquid Society. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2017. https://archive.org/details/chroniclesofliqu0000ecou

Gibson, James. J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Psychology Press

Törnberg, K.P. (Petter). “Social media polarize politics for a different reason than you might think”. University of Amsterdam. 2022.https://www.uva.nl/en/shared-content/faculteiten/en/faculteit-der-maatschappij-en-gedragswetenschappen/news/2022/10/social-media-polarize-politics-for-a-different-reason-than-you-might-think.html?cb

Collaborators:

Siming Liao, Aubrey Ventura