Upon reading Ingold’s “Making”, we discovered that Martin Heidegger, a German Philosopher and one of the most important thinkers of modern times, was cited numerous times to support the text’s main arguments. Born in 1889, Heidegger published his first major work, “Being and Time”, at the age of 1933, when he was recognised for his philosophical contribution to phenomenology and the movement of existentialism. In philosophy’s realm of metaphysics, Heidegger focuses on the study of fundamental ontology, which can be more easily understood as the study of “what it means for something to be”. In Ingold’s “Making”, 4 of his other works are cited, which are ”Poetry, Language, Thought” (1971), “Parmenides” (1972), “Basic Writings” (1993) and “The Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics: World, Finitude, Solitude (1995).

From these works of Heidegger, his diatribe against the typewriter was used to support Ingold’s argument in the chapter “Drawing the Line”, as well as in the chapter “Telling by Hand”, where the philosopher’s criticism of technology’s effects on human essence was employed. His fundamental ontology was also greatly useful to Ingold’s, as in the chapter ”Round mound and earth sky”, it was drawn to make the important distinction between an object and a thing, where “people” are said to fall into the latter of these two categories of existence. So, in summary, we can see that Heidegger’s Philosophy laid the essential foundation for Ingold’s main arguments in these three chapters, but how exactly do they support the text in “Making”?

The Object at Hand…

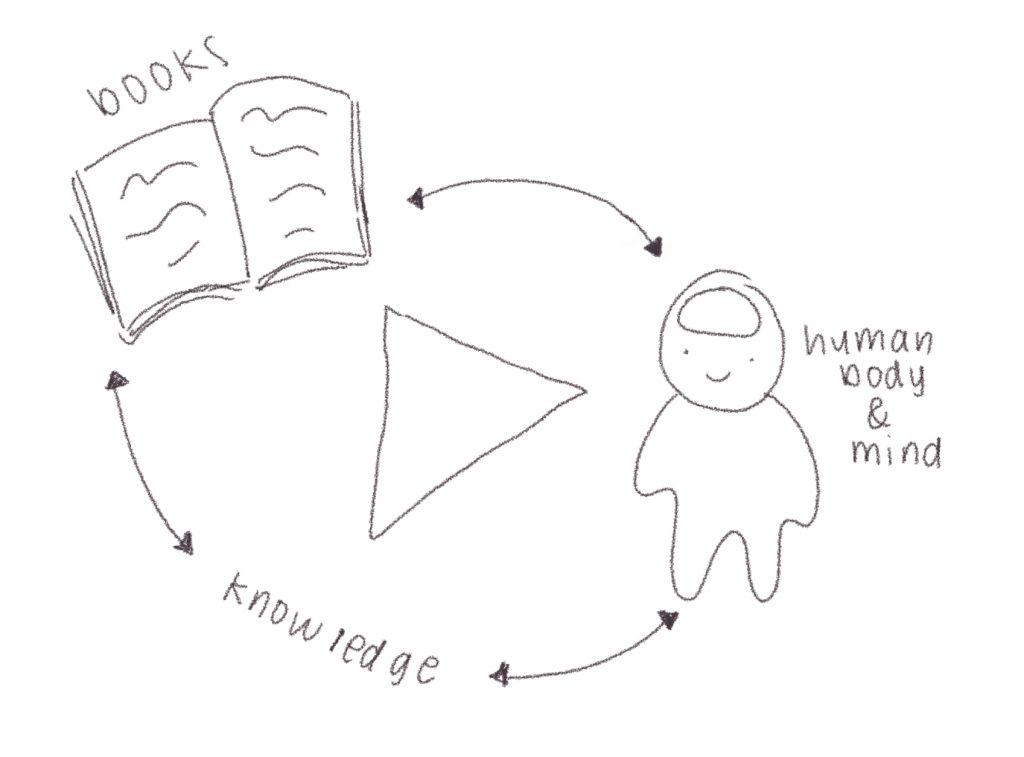

For Heidegger, the category of an object is definable as being “complete in itself”. The confrontational “over-againstness” that characterises an object can be understood by the example of a chair. We may look at the chair and interact physically with it, but there exists an invisible distance between us and the chair as an object, for we are unable to join in with the process of its formation. In short, an object exists independent of our perception of it and is in itself complete. A thing, on the other hand, Heidegger defines as a “coming together of materials”; it is fluid and inviting. When we interact with a thing, we do not experience such a distance as with an object, and, as such, “people” would be considered a thing under this definitive categorisation.

Further in the chapter “Telling by hand”, Heidegger challenged the notion that human essence lies in the mind, proposing a focus on the hand instead. He argued that rather than being a mere instrument of the mind, the hand is the precondition of the possibility of having instrumentality. Hence is the saying, having a thing “at hand”, even when it is intangible, such as an upcoming event. For Heidegger, humans having hands is the fundamental essence that differentiates man from mere animals, as we are creatures capable of “world-forming”. On the other hand, he insists humans do not “have” hands, rather the hands hold the very essence of what makes us human to our core (Parmenides, 80). The hand offers us a world of contradictions; through our hand, we can enact greetings, commit murder, and even document the world.

The Irony of Typing…

In his work, Parmenides, he deepens his perception of the hand to an extension of communication. He explains, handwriting is defined to be words as script (by the hand), and inasmuch as it holds the pen, it also holds one humanity; this is the essential difference between writing and typing with a typewriter. He describes typing as a transcript or a preservation of the handwritten word. In the realm of writing, the typewriter has essentially robbed the hand of its power. Now the act of typing affords a sense of anonymity over the more personalised counterparts; the handwritten words contain meaning beyond the text’s inherent interpretation. Ingold highlights Heidegger’s aversion to the typed word; “with scarcely disguised revulsion, ‘writes “with” the typewriter’. [Heidegger] puts the ‘with’ in inverted commas to indicate that typing is not really a writing with at all”(Making, 122). The hand loses its agency and signature on its writing. Stripped down to its core meaning by type, he claims the very essence of each individually written word is misunderstood when labelled as “the same when typed”. (Heidegger would NOT like this work…) To tell, or more specifically, write a story, one must feel the world and be in the world. Through type, experiences, stories, and lives are reduced to transmissions of encoded information.

Ingold’s Refute

Although Heidegger has some interesting interpretations on the human interaction with media, Ingold notes that Heidegger is a rather bitter older man. Most of his work is obsessed with picking apart the rise of technology and the decay of humanity in response. In comparison he showcases Leroi-Gourhan, a genuine technology enthusiast who encouraged the rise of technology in place of human’s inferior physiological forms. Through the many objects our hand holds, Ingold notes–above all–the hand of others to be held, both in guiding and to be led by the hand. He lingers on the distinct qualities of the human hand, down to the anatomy. Not only does he note the importance of the hand, but the hierarchy of fingers, for the finger may offer feeling and touch, yet it cannot hold without help from the thumb. Through the vehicle of typing, he compares other similar extensions of the hand. He questions a forklift driver’s ability to feel the weight of the load he lifts. Aside from the otherwise two-dimensional medium of typing, he also notes the sensation of the keys while typing, and questions if the typist notices the nuance in shape.

As a fierce guardian of the physical, manual space, Heidegger strongly disavows the integrity of technological assistance and its ability to portray a meaningful story. In this interpretation, the very act of typing in favour of writing, strips inherent depth from a piece. He emphasises the value of the human hand as the pinnacle symbol of the essence of humanity.

Maxine Gray & Nam Pham