In the chapter “Telling by hand”, we see Ingold proposing a very interesting concept that is the “humanity of the hand”. Where the author argues, with help from Heidegger’s philosophy, that it is in the hands that the essence of humanity lies. Other senses of perception, the eyes, the nose and the ears, do not afford us the ability to tell stories the way the hand does. It could very well be said that with our eyes, nose and ears, we perceive the world while through our hands, we shape it into form. With our hands – the supreme among the organs of touch, we write, we draw, we thread and as such, we are able to tell stories to the world.

Humans and the Language of Hands

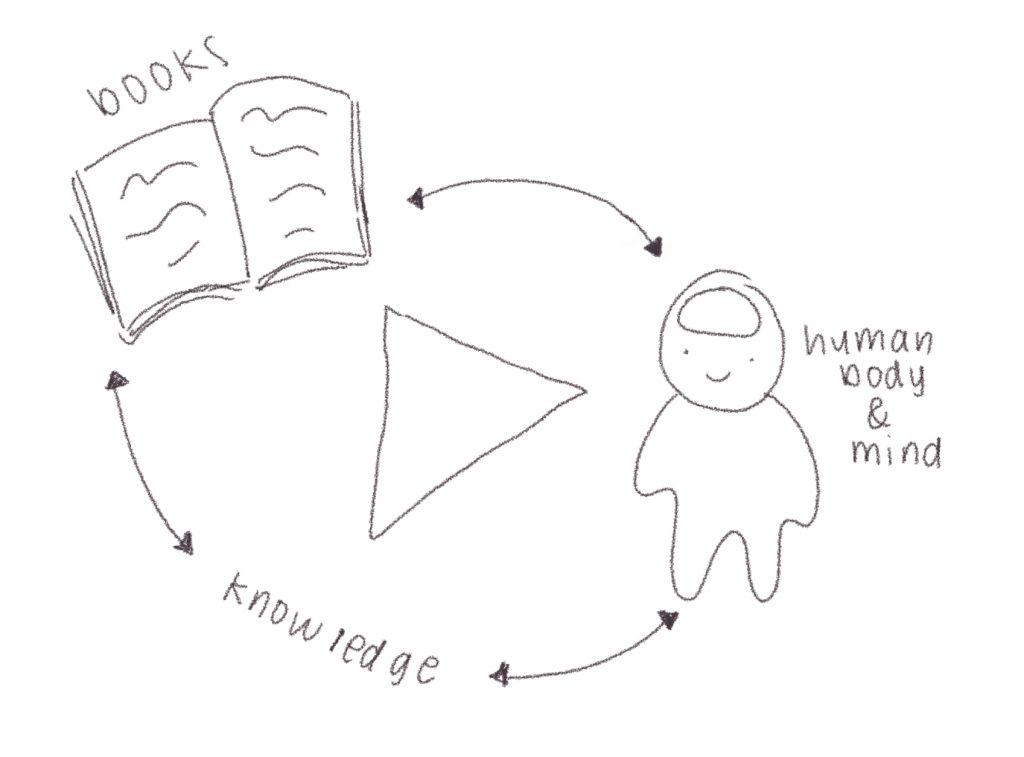

According to the famous German thinker – Martin Heidegger, the hand is no mere instrument, for only with it came the very possibility of instrumentality. Supported by anatomist Frank Wilson’s claim that the hand exists as an extension of the brain and not a separate device under its control. The brain reaches out into the hands and from there it reaches out into the world. The hand is what separates us from mere animals, but it is not because we have opposable thumbs, nor the fact that we have flexible fingers that move independently, equipped with nails instead of claws. For Heidegger, it is language that holds the hand, which in turn is what holds man. For him, words as the essential realm of the hand provides the stable base in which humanity is grounded.

For this exact reason, animals are considered by Heidegger to be “poor-in-the-world”, for they lack the essence of “world-forming” that characterizes man, an essence afforded to man by the hand. “Humanity” thus, challenges man by opening up for man a world that is not simply given, but one that must be unraveled to be properly understood. The task of the hand as follows is to tell, one must write, one must draw, only then may one’s world be properly formed.

As such, for the German philosopher, writings only truly tell (a story) when it is written by hand, as opposed to text produced through a typewriter. He argues that the human eye’s script is interpreted as the form of writing that tells and through holding the pen, the hand expresses our humanity. A humanity that starts with the essential “being” which then allows us to “feel”, and it is through that feeling that we start to “tell”. This is exactly what the typewriter has taken away from us – our humanity, for to type is not to write at all, and the typewriter paradoxically stops us from writing, an act that inevitably silences us from telling.

Stories of Screens, Scrolling, and Smartphones

Ingold’s concept of the “humanity of the hand” can be further extended to the contemporary act of typing on our smartphones. This specific process of mediation reveals how our hands continue to mediate thought and feeling, even in a digital context removed from the material intimacy of pen and paper. While Heidegger mourned the typewriter’s detachment of writing from the hand, the way we send texts today further complicates this separation and disconnect. It can be argued that touchscreens still demand the tactility of our fingers, but the gestures we make with every tap, swipe, and scroll, completely transform writing into a choreography of minimal movements. Hence, the new generation is being taught both this choreography alongside writing by hand simultaneously, resulting in a generational difference and new ways of perceiving and telling stories.

In handwriting, the thumb is peripheral and supports the pen that is the main object of mediation, whereas in texting, the thumb becomes the primary storyteller. Every new development to our smartphones reduces the thickness of our screens and consequently the distance between our fingertips and the world within our devices. The thin glass screen acts as an invisible barrier, creating the illusion that all forms of mediation are coming directly and instantaneously from our fingertips, almost as if we have become one with our devices.

Today’s digital age creates endless possibilities for our bodies to craft messages, emotions, and relationships. With every communication platform competing for users’ attention, people are always building connections through new innovative ways. Whether that is through texting, calling, reposting, sending stickers, or even Instagram reels, the overstimulating combination of text, audio, and visuals convey more than words simply could. The rise of meme culture on the internet invented a new way to express oneself, which is to make references to other preexisting media. This way, our internal thoughts and feelings, even those that we are unable to fully express, can be mediated with massive external reach, all from the from our fingertips.

Through these rapidly changing technologies, our bodies constantly translate feelings into digital traces. Instead of leaving fingerprints on tangible objects we touch, we leave digital footprints after every interaction. Furthermore, this enables your smartphone to then reconfigure its role in mediation. Regardless of its convenience and innovation, nothing can compare to the feeling of holding a physical handwritten letter. There is power in the warmth of touch that is now reduced to the cold surface of glass. Ultimately, our fingers’ ability to edit before sending and our habitual scrolling creates a new expression of the hand’s humanity, emphasizing the negotiations between intimacy and distance in the mediated fabric of modern communication.

The Typewriter Returns

Comparing this with Heidegger’s pessimistic opinion of technology, and specifically the typewriter, we can imagine his stance on the disconnect between the hand and smartphone. Through a handwritten letter, we receive more than the words on the page. We see the erased or crossed-out attempts, the personality in the way each “i” is dotted, or even an ink smudge from writing too fast. As we adapted to using typewriters, we lost the sense of humanity and personality in handwriting. However, through the typewriter, we still see a lingering sense of intention beyond the words, we can see the “x”-ed out phrases, creased paper corners, or even a coffee stain on a message written late at night. Evolving into the smartphone, we lose more of these unintentional material stories that linger in each message. With the ability to unsend, edit, and pre-send our messages, we so ingenuinely mediate our communication to a point where we have lost our humanity.

In distinguishing ourselves from other animals, Heidegger emphasizes the strength of the hand in the realm of communication, or more importantly, storytelling. Despite the capabilities of this dexterity, we find our communication regressing to selections of premade facial expressions–emojis. When considering interpersonal communication, we see this grasp of personalisation among the monotonous, identical fonts in messaging systems. In place of personalised handwriting styles, some find ways to change their typing font. In place of crossed-out phrases and typos, some retype their messages rather than editing or deleting . As such, with the dramatic development from the typewriter to today’s smartphone, the typewriter maintains more personalised humanity in comparison to the smartphone. Perhaps if Heidegger could re-evaluate, his interpretation would cut the typewriter some slack.

Courtesy of Kim Chi Tran, Maxine Gray, Nam Pham