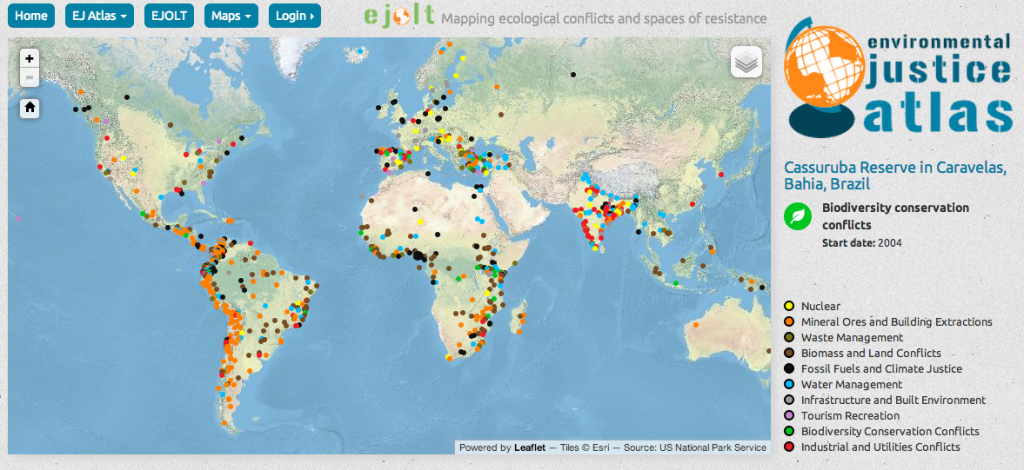

Consider this strategy suggested by Ali McCannell, a UBC graduate student ~ if you want to know what matters to people in a particular community, city, country visit a convenience or corner store and see what’s for sale. Her example was from her time spent teaching in Korea where she noted the following commonly available items in pretty much any small shop: “grooming items, booze, double eyelid tape, a huge selection of yogurt drinks, kimchi and worm larvae.” I won’t speculate on what that list might mean, but at first glance it speaks volumes. What’s in your corner store?

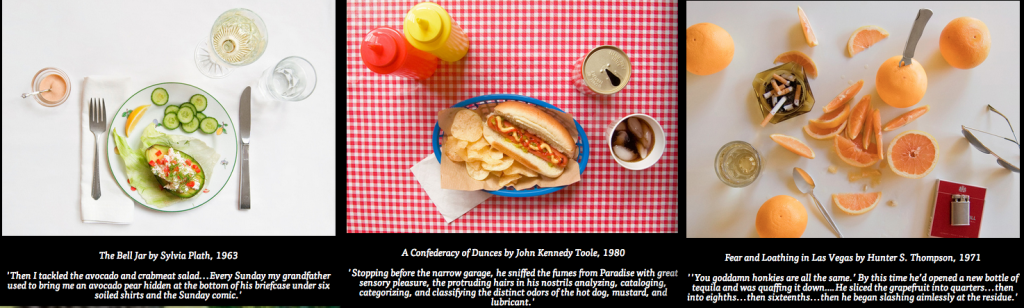

People’s stuff can be interesting and useful in a range of research methodologies. For example, in narrative research one might collect and analyze stories but look also to people embedded in their environment, including how they talk about it. Although not social science per se, a new book Artists, Writers, Thinkers, Dreamers: Portraits of Fifty Famous Folks & All Their Weird Stuff illustrates such connections. While this book is more a novelty, it does illustrate the interconnections between people and the things they use, surround themselves with and value. It gives us an idea of how to think about objects in relation to social meaning of lives and equally important it illustrates how those connections might be represented beyond text based descriptions.

Follow

Follow