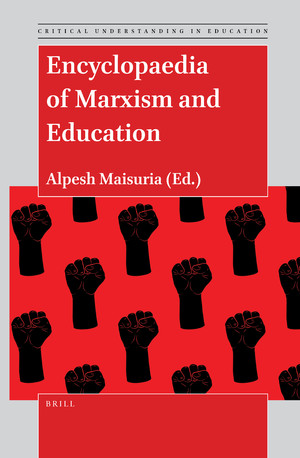

Brill has just published the Encyclopaedia of Marxism and Education, edited by Alpesh Maisuria, who is a professor in Education Policy in Critical Education at the University of the West of England, Bristol, UK.

“This encyclopaedia showcases the explanatory power of Marxist educational theory and practice. The entries have been written by 51 leading authors from across the globe. The 39 entries cover an impressive range of contemporary issues and historical problematics. The editor has designed the book to appeal to readers within the Marxism and education intellectual tradition, and also those who are curious newcomers, as well as critics of Marxism.

The Encyclopaedia of Marxism and Education is the first of its kind. It is a landmark text with relevance for years to come for the productive dialogue between Marxism and education for transformational thinking and practice.”

I co-authored, with Sandra Mathison, a chapter titled “Critical Education” for EME. In this chapter we define critical education broadly as a field or approach that works theoretically and practically toward social change that anticipates a post-capitalist world. We explore multiple foundational sources for critical education including Marxism and critical theory, but also democracy and anarchism. And finally, we provide an overview of several manifestations of critical education. While many conflate critical pedagogy with critical education, we contend critical education has a broader reach.

Please contact me if you would like a copy of our chapter on critical education, as I have a limited number of offprints I can share.

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements

List of Figures and Tables

Notes on Contributors

1 Introduction

Alpesh Maisuria

2 The 4th Industrial Revolution, Post-Capitalism, Waged Labour and Vocational Education

James Avis

3 Alienation and Education

Richard Hall

4 Alternatives to Capitalism

Peter Hudis

5 Capital Accumulation and Education

John Fraser Rice

6 Colonialisms and Class

Spyros Themelis

7 Communism: The Party – Pedagogy and Revolution from Marx to China

Collin L. Chambers and Derek R. Ford

8 Corporate State: “Downhill All the Way” – Education in England from Welfare to Corporate State

Patrick Ainley

9 Critical Education

Sandra Mathison and E. Wayne Ross

10 Critical Realism

Grant Banfield

11 Cuban-Marxist Education

Rosi Smith, Leticia de las Mercedes García Rosabal and Maikel J. Ortiz Bosch

12 Dialectical Materialism (Materialist Dialectics)

Constantine (Kostas) Skordoulis

13 Disaster Education

John Preston

14 Early Childhood, Feminism, and Marx

Rachel Rosen and Jan Newberry

15 Employment: Education without Jobs – Young People, Qualifications, and Employment in 21st Century Britain

Martin Allen

16 Ethnography of Education and Marxism: Education Research for Social Transformation

Dennis Beach

17 Freire, Paulo (1921–1997) as a Marxist Revolutionary for Education

Juha Suoranta

18 Gramsci, Antonio (1891–1937): Culture and Education

Peter Mayo

19 Green Marxism

Simon Boxley

20 Guevara, Ernesto “Che” (1928–1967)

Peter McLaren and Lilia D. Monzó

21 Intersectionality: Scaling Intersectional Praxes

Gregory Martin and Benjamin “Benji” Chang

22 Lenin, Vladimir (1870–1924) and Education

Juha Suoranta and Robert FitzSimmons

23 Liberation Theology

Peter McLaren

24 Luxemburg, Rosa (1871–1919) and Education

Julia Damphouse and Sebastian Engelmann

25 Managerialism and Higher Education

Goran Puaca

26 Marxism and Education: [Closed] and … Open …

Glenn Rikowski

27 Marxism and Human Rights against Capitalism

Daniel Hedlund and Magnus Nilsson

28 Marxist Feminism and Education: Gender, Race, and Class

Sara Carpenter and Shahrzad Mojab

29 Middle Classes of the World

Göran Therborn

30 Neo-Liberalism and Revolution: Marxism for Emerging Critical Educators

Alpesh Maisuria

31 New Left, Anarchism and Education

Nick Stevenson

32 Palestine: Education in Mandate Palestine

Bernard Regan

33 Plebs League: Towards a Modern Plebs League

Colin Waugh

34 Postdigital Marxism

Petar Jandrić

35 Poverty: Class, Poverty and Neo-Liberalism

Terry Wrigley

36 Public Pedagogy

Mike Cole

37 Public University: The Political Economy of the Public University

David Harvie, Mariya Ivancheva and Robert Ovetz

38 Social Class: Education, Social Class and Marxist Theory

Dave Hill and Alpesh Maisuria

39 State and Private Capital: Education, State and Capital

Ravi Kumar and Rama Paul

40 World-Systems Critical Education

Tom G. Griffiths

Index