In Arts One this week we discussed City of Glass in two versions: the original novel by Paul Auster, and a graphic novel adaptation by Paul Karasik and David Mazzucchelli. We only had one seminar discussion on these two works rather than the usual two we have in a week, due to the Easter holiday. As a result, there is a lot that we didn’t get to talk about.

Paul Auster, 2008, by David Shankbone on Wikimedia Commons, licensed CC BY-SA 3.0

I puzzled over many things in these works, but the one I decided to write about here started off with me asking myself the question: this is a novel about a writer of mysteries, but is it a mystery novel itself? And if so, what is the mystery and how might we solve it?

We did talk a bit about this question, as it came up when a student brought up something similar in class. But I wanted to share some of the thoughts I came up with when thinking about it before class. And perhaps, while writing them down here, I’ll come to some further clarity. Or maybe not.

I didn’t read any secondary sources on these texts before writing this, and I expect there is a great deal that has been written about these very questions. I try to challenge myself to come up with my own interpretations before reading anyone else’s. So it could very well be that what I say below is proven wrong by someone else’s more expert reading. I’ve tried to provide textual evidence to support this as a possible reading though.

What’s mysterious?

We don’t have to take this as a mystery novel, of course, and for reasons we discussed in class it might be better thought of as a novel about mystery novels. But I still find some things mysterious in it. Of course, these are not wrapped up nicely in answers as in traditional mystery novels:

- Why are there two Peter Stillman Sr.’s?

- In lecture a possibility was discussed that this could be an embodiment of the possibility of the story of a writer going in different directions, and which direction is chosen is somewhat arbitrary.

- What happens to Peter Stillman Jr. and Virginia Stillman? Why do they disappear?

- What happens to Quinn? Where does he disappear to?

- Who is the “author”/narrator of the novel?

Now, maybe some of these questions are not meant to have answers. But I did pursue some thoughts about the last two.

What happened to Quinn at the end?

I came to an answer for this pretty quickly; the graphic novel helped me see it more clearly. None of this is to say that this is the answer, but it’s one that I think makes sense.

When Quinn goes to the room in the Stillmans’ apartment and basically fades away while writing in the red notebook, the darkness starts taking over more and more from the light, and he has less and less time to write in his notebook (Auster 199). And the notebook is running out of pages. These two things are correlated:

The period of growing darkness coincided with the dwindling of pages in the red notebook. Little by little, Quinn was coming to the end (Auster 199).

Quinn was coming to the end of the red notebook, but also to the end of himself: after he discovers that someone else is living in his apartment, that he has no more home, no more job with the Stillmans, he realizes that he has “come to the end of himself” (Auster 191).

Quinn as a character on a page

This suggests a close connection between writing in the red notebook and the existence of Quinn himself. Of course, he existed as a character before buying the red notebook, but at the end, as the notebook runs out of pages, and Quinn slowly stops writing in it, the darkness starts taking him over–he fades away, one might think. His existence at this point and the existence of pages in the notebook seem to coincide. Which in turn suggests that he is little more than a character on a page; when the pages run out, he runs out.

At least, he runs out as the person he was. Just as he had become a different person while keeping watch over the Stillmans’ apartment (Auster 183), he might become a different person when the pages of the red notebook run out. He tries to remember his life “before the story began” (Auster 195), the books he had written as William Wilson, his former agent; but it was difficult and he soon “waved good-bye” to his former life (195). As he continues to write in the notebook, he stops writing about himself: “Quinn no longer had any interest in himself” (200).

He disappears, but perhaps he just disappears as Quinn.

Quinn as a character on a page in the graphic novel version

David Mazzuchelli in 2012, by Luigi Novi on Wikimedia Commons, licensed CC BY 3.0. © Luigi Novi / Wikimedia Commons

The graphic novel could be said to illustrate the idea of Quinn disappearing as the pages in the notebook disappear. As one of our students talked about in class, the panels during the period that Quinn is in the room writing in the notebook start to become more chaotic. Whereas before they were regular, with even spacing between even if they were different sizes, at this point they start to have chaotic spacing until they completely fall apart towards the end. This student said that before that, there are indications that we are looking into the story and Quinn’s life as through a window, but now I can’t for the life of me remember what he was saying about this and how it changes when the panels fall apart (I hope he soon posts his argument on our blog site!).

One thing this does for me is make it feel less like we are looking in on a story that is happening as if in “real life” (at least, a sense of real life as one gets in fiction), and more like we are reading a story on a page. When the panels fall apart towards the end and become clearly like pieces of paper, it brings to mind for me the fact that these are pieces of paper we are reading, that this is a book, that the story isn’t, after all, real and Quinn is actually just a character on a page.

Of course, this really is what he is; a character on a page. But the book is foregrounding this, making us aware of it, pulling us out of the immersion in the story where we have a sense that he’s kind of real…in the story at least. I’m reminded of what we talked about with Laura Mulvey, how she discusses that film sometimes tries to keep us immersed, to make the camera disappear, as it were, or at least fade into a simulated reality so we don’t pay attention to what the camera is doing. And how film can bring the filmic medium and the camera to the forefront, such as with the 360 degree pans we watched in class from her film Riddles of the Sphinx.

In the graphic novel, in the two-page spread on 130-131, he himself depicted pictorially in a way that suggests this as well. On the bottom of 130 and on 131 he is shown diving or falling into water with a pen in his hand, the pen going first into the water and the rest of his body following. It’s as if he is writing his way into the water. But the water on the page turns into just blank white pages that fall away into the darkness on 131 and 132-133. He is disappearing into the pages; he is nothing more than the pages in the book.

Another interesting thing about this, though, is that as he himself as a character experiences darkness (the more he starts to disappear, to fade way as a character, as Quinn, the more he experiences darkness), the pages turn white. Again, this suggests he exists only on the page. As he disappears, the page becomes blank.

Who is the author/narrator?

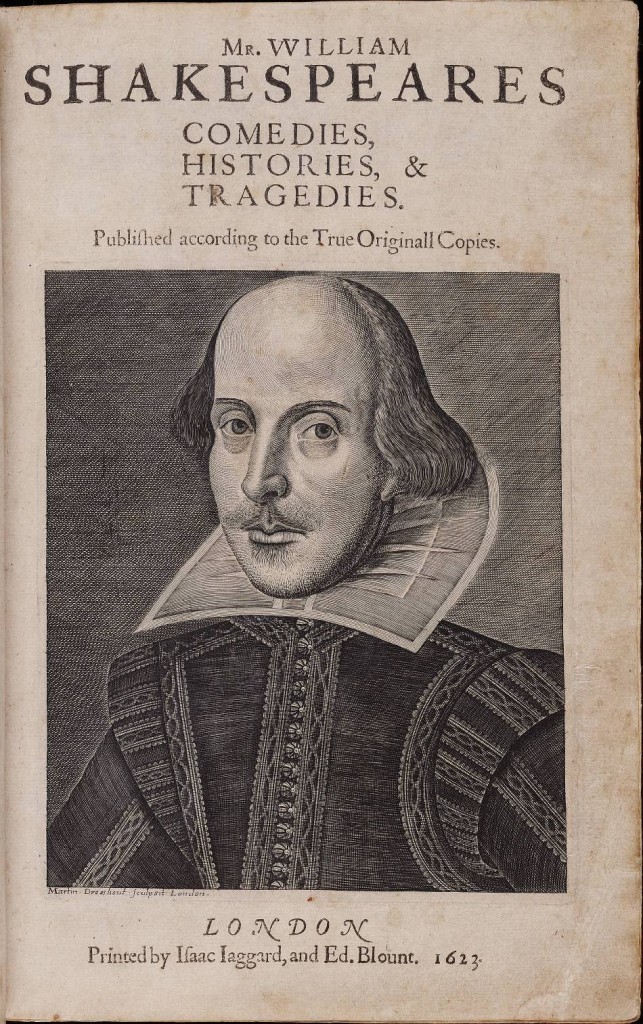

So Quinn the character on a page disappears as he stops writing in the notebook. Who was he written by? Paul Auster the author, of course, who wrote the whole book. But what about the book within the book, as Auster the character in City of Glass talks about with Cervantes’ Don Quixote? Who is the author/narrator in Auster’s novel City of Glass, as he appears towards the end of the text (starting on p. 173)? Maybe there isn’t supposed to be a clear answer to this, and maybe I’m just making stuff up, but here are some thoughts.

The graphic novel could suggest one answer to this question, in part through different fonts. If you look closely, there are different fonts for different characters:

- “author”/narrator: like typewriter (1, 89, 107, then at end)

- Quinn and the voiceovers in the story (not the narrator as standing out as a narrator) have the same font

- Peter Stillman Jr. on the phone (6, 11) and in person (starting p. 15) have different fonts than those for Quinn

- Max Work has a strong font p. 7

- Peter Stillman Sr has stylized capital letters (66-67, etc.) and his speech bubbles also have sharp corners

- Daniel Auster’s speech bubbles have slightly different font (95)

- On 102-103, the panels have a different font to show that these words are what Quinn is writing in his notebook

One thing the graphic novel suggests with font styles is that perhaps Quinn himself is the  author/narrator who appears towards the end. The very last page starts off with the narrator speaking in the typewriter font, and then the last sentence is back in the notebook. I suppose there are a number of ways to interpret this, but one way could be to connect the typewriter narrator to the Quinn that was writing in his notebook. The same words that appear in Auster’s novel as coming from the same voice, in the graphic novel appear in two different fonts, one clearly connected to Quinn as the character who wrote in the red notebook.

author/narrator who appears towards the end. The very last page starts off with the narrator speaking in the typewriter font, and then the last sentence is back in the notebook. I suppose there are a number of ways to interpret this, but one way could be to connect the typewriter narrator to the Quinn that was writing in his notebook. The same words that appear in Auster’s novel as coming from the same voice, in the graphic novel appear in two different fonts, one clearly connected to Quinn as the character who wrote in the red notebook.

Remember that “Quinn did all his writing with a pen, using a typewriter only for final drafts” (Auster 62). We might think that the notebook pages are his first drafts, and the typewriter is when he came later to write the story up in a final form.

So though Quinn as a character on a page disappears as the story winds down to a close, Quinn as an author starts to appear. The “author” as narrator starts to make conspicuous appearances as Quinn starts his vigil outside the Stillmans’ apartment (Auster 173), which is arguably when he starts to fall apart. Then, when Quinn the character disappears completely the “author” comes in and takes over.

The graphic novel suggests this reading in another way as well. The last three pages of the graphic novel are written in a different style, as we discussed in class: they don’t have clear panels, and the images seem more realistically drawn. That would connect to the fact that at this point in Auster’s novel, it is purely the “author”/narrator’s voice we are getting. But I noticed something else: the pictures on the first of those last three pages mirror pictures on p. 113, from when Quinn was doing his watch of the Stillmans’ apartment. At that point, Quinn leaves his seat and walks to try to get some more money, so it looks to me like the path away from the Stillmans’ apartment.

If this is the case, then why would the same path away from the Stillmans’ apartment be being followed by the author/narrator at the end? After all, in that part of the story the author/narrator is going towards the Stillmans’ apartment, if anything, since he and Auster go there to try to find clues about Quinn. Again, one possible reading of what the graphic novel is doing is that the author/narrator is coming out of the apartment because that is where he, Quinn the character, last was. Quinn the author/narrator emerges from the place where Quinn the character disappeared.

Authors putting themselves in books

Yes, I’ve gone pretty far in my flights of fancy here. But I think there’s a certain logic to it. And it fits with Paul Auster (the author) putting himself into his own book as a character–maybe Quinn (the author) is putting himself into his own book as a character. Maybe Quinn the author had to write himself away as the character who is in despair, who doesn’t really exist except as William Wilson or Max Work; maybe he had to get rid of that self in order to emerge as a writer again.

Since his wife and son died, and before the case with the Stillmans began, he wrote only as William Wilson. In those five years, Quinn had stopped being an author, and had already started to fade away:

Quinn was no longer that part of himself that could write books, and although in many ways Quinn continued to exist, he no longer existed for anyone but himself (Auster 9).

He had, of course, long ago stopped thinking of himself as real. If he lived now in the world at all, it was only at one remove, through the imaginary person of Max Work (Auster 16).

Perhaps, when he starts writing about the Stillman case in the red notebook, he starts to exist as an author again. Note that in the notebook where he starts writing about the Stillman case, and in my reading where he starts writing the story that later becomes this book with him as the author/narrator, he puts “Daniel Quinn” on the notebook: “It was the first time in more than five years that he had put his own name in one of his notebooks” (Auster 64). If the notebook is connected to this book itself, where this book is the final draft in typewriter form and the notebook is his earlier notes, then this, too, suggests to me that he is the author/narrator who appears later. He is able to become a writer again, in that case.

Perhaps, when he starts writing about the Stillman case in the red notebook, he starts to exist as an author again. Note that in the notebook where he starts writing about the Stillman case, and in my reading where he starts writing the story that later becomes this book with him as the author/narrator, he puts “Daniel Quinn” on the notebook: “It was the first time in more than five years that he had put his own name in one of his notebooks” (Auster 64). If the notebook is connected to this book itself, where this book is the final draft in typewriter form and the notebook is his earlier notes, then this, too, suggests to me that he is the author/narrator who appears later. He is able to become a writer again, in that case.

But he is no longer a writer as Daniel Quinn the character, though, which is a problem with my reading. The author/narrator refers to Quinn as having disappeared. And Quinn as character does. As noted above, he disappears as Quinn the character, but might emerge as someone else. Maybe Daniel Quinn the writer, or maybe an unnamed author/narrator. In either case, the author/narrator says at the end that Quinn “will be with me always.” Why? Because he is a part of the author/narrator, a former self, I’m arguing.

Don Quixote…what’s up with that?

So if this reading makes any sense, then it would be like Auster writing a novel in which he creates a character as himself, and Quinn doing the same. But I expect there’s a lot more to this idea of authors putting themselves in books than I’m getting, with the whole Don Quixote story within this novel. Don Quixote, in Auster’s (the character’s) article, doesn’t so much write his own story as orchestrate others writing his story with him as a character in it. I went down that rabbit hole, trying to connect Daniel Quinn to Don Quixote as we are invited to do with the initials being the same, but came up empty on that path.

Well, this has turned into a gigantic post (over 2500 words!). I think I’ve exhausted all the ideas I had on these topics, but would be happy to hear what others think!