I wrote the following narrative for a teaching award application, and someone has requested that I post it openly as well, as it may be useful to others. I’m happy to do so! (Update July 18, 2015: unfortunately, I didn’t get the award, but you can see my entire application for it in this post).

This was a section of the application where I describe the basics about what open education is. I then go on, after this, to talk about how I engage in open educational activities in my own work. I might post those sections here later, in separate posts.

If you want to learn more about open education, there is also a great ebook called The Open Education Handbook. David Wiley has created an open course on open education, here: https://learn.canvas.net/courses/4

And here is the open education course at the Open University in the UK that I took in 2013. My blog posts from that course are here.

What is open education?

Financial, legal, technological openness: open educational resources

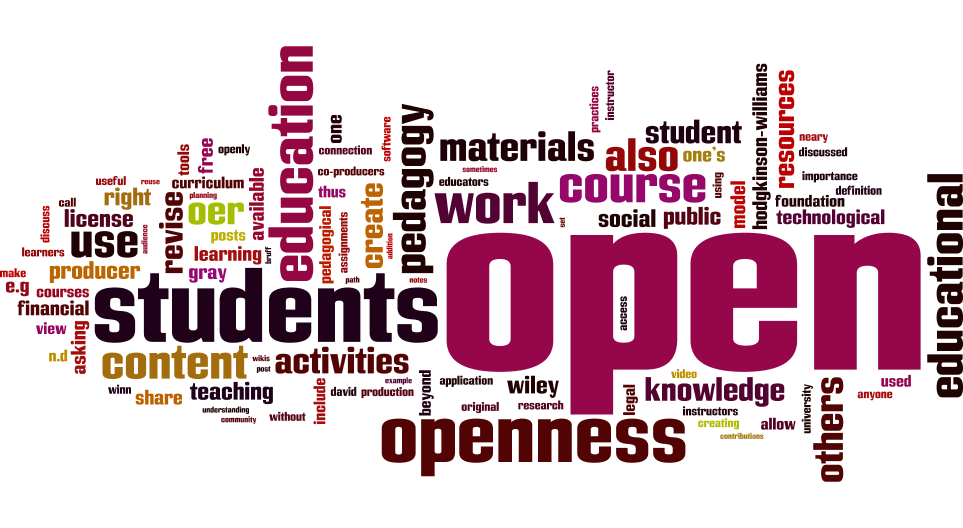

What is open education? To start, it is useful to consider the various meanings the word “open” can have in “open education.” Hodgkinson-Williams and Gray (2009) give a useful overview of some of these meanings, including what they call “financial openness,” “legal openness,” “technological openness, and “social openness.”

A common understanding of “open” is “free,” as in free of cost, or what Hodgkinson-Williams and Gray (2009) call “financial openness.” This is the meaning one might immediately think of as associated with Massive, Open, Online Courses. These are courses that are available for anyone with a reliable internet connection to take, free of cost.[1] Financial openness is also exemplified when a teacher makes a set of lecture notes, essay topics, a video, an image, etc. available for others to use without a fee.

“Legal openness” refers to the degree to which teaching materials, student work, research and more are licensed to allow others to reuse, revise, and redistribute. Some MOOCs, for example, may only allow you to view materials, not download them to revise or share them with others.[2] The “Open Definition” by the Open Knowledge Foundation addresses this meaning of open directly: “Open means anyone can freely access, use, modify, and share for any purpose (subject, at most, to requirements that preserve provenance and openness)” (Open Knowledge Foundation, n.d.). David Wiley, in a widely-used definition of “open content,” lists similar requirements for openness, and labels them the “five R’s”:

-

Retain – the right to make, own, and control copies of the content (e.g., download, duplicate, store, and manage)

-

Reuse – the right to use the content in a wide range of ways (e.g., in a class, in a study group, on a website, in a video)

-

Revise – the right to adapt, adjust, modify, or alter the content itself (e.g., translate the content into another language)

-

Remix – the right to combine the original or revised content with other open content to create something new (e.g., incorporate the content into a mashup)

-

Redistribute – the right to share copies of the original content, your revisions, or your remixes with others (e.g., give a copy of the content to a friend) (Wiley, n.d.)

Wiley argues that the more of these five activities that are allowed, the more “open” a work or set of materials is. How one alerts others to the possibility that they can use one’s work in such ways is through an open license, such as a Creative Commons license. [3] Giving one’s work an open license means that one retains copyright, but allows others to use, share, and sometimes also revise the work without asking permission each time.

Hodgkinson-Williams and Gray (2009) also discuss “technological openness,” which refers to the use of different sorts of software tools. Those that are open source are more open technologically than those that are not. In addition, tools that allow for easy editing by anyone, without having to purchase the software, are more open: thus, documents in Open Office or Google Documents are considered more open than those in Microsoft Word. Both David Wiley and “The Open Definition” also acknowledge the importance of technological openness: if a work can only be edited using tools that are very expensive, or that only run on certain platforms, or that require a high level of expertise, it is less open.

Open education is often discussed in terms of using or creating “open educational resources,” or OER—these combine financial, legal, and technological openness. According to the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation,

OER are teaching, learning, and research resources that reside in the public domain or have been released under an intellectual property license that permits their free use and re-purposing by others. Open educational resources include full courses, course materials, modules, textbooks, streaming videos, tests, software, and any other tools, materials, or techniques used to support access to knowledge (William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, n.d.).

Thus, syllabi, lecture notes, video recordings of lectures, slides, animations, assignments, podcasts, and more can be OER, so long as they are given an open license. Engaging in open education can be as simple as assigning one or more OER for students to read, hear, watch in one’s classes, or creating OER for others to use, revise and share themselves.

Social openness: open pedagogy and students as producers

Finally, Hodgkinson-Williams and Gray (2009) discuss “social openness”: “the willingness to make materials available beyond the confines of the classroom by lecturers, students and university management” (p. 105). Social openness not only involves making teaching materials available to a wider audience, but also engaging in more collaborative activities among students, between students and instructors, and between both and the wider community. Hodgkinson-Williams and Gray (2009) point to a range between (1) lecturer-centred openness, in which, for example, an instructor creates all curriculum materials and shares them openly, to (2) more student-centred openness, involving students contributing to the curriculum through adding content in things such as blogs and wikis, to (3) inviting contributions and collaborations between students, instructors, and members of the public—such as through connecting with professionals in the field (p. 105).

Similarly, the Cape Town Open Education Declaration, drafted in 2007 and currently signed by nearly 2500 individuals and over 250 organizations, focuses on creation and use of OER; but it also emphasizes changing one’s pedagogy to invite more collaboration between instructors, students and the public:

We are on the cusp of a global revolution in teaching and learning. Educators worldwide are developing a vast pool of educational resources on the Internet, open and free for all to use. These educators are creating a world where each and every person on earth can access and contribute to the sum of all human knowledge. They are also planting the seeds of a new pedagogy where educators and learners create, shape and evolve knowledge together, deepening their skills and understanding as they go (“Cape Town Open Education Declaration,” 2007).

Such collaborative pedagogical approaches are sometimes referred to as “open pedagogy.” Wiley (2013) defines open pedagogy as educational activities that are only possible because materials are made available with an open license. Examples he gives include: asking students to revise and remix OER that are used in a course in order to create tutorials for aspects of the course that students often struggle with, and asking students to create or edit Wikipedia entries on topics discussed in a course. Similarly, though using a different term, Ehlers (2011) labels such activities “open educational practices”: “practices which support the (re)use and production of OER through institutional policies, promote innovative pedagogical models, and respect and empower learners as co-producers on their lifelong learning path” (p. 4). Open educational practices, like Wiley’s view of open education, involve the use and creation of OER in courses where learners are collaborators and co-producers of the curriculum. Thus, “[t]he pure usage of … open educational resources in a traditional closed and top-down, instructive, exam-focused learning environment is not open educational practice,” according to Ehlers (2011, p. 5), but doing so in the context of a course where students revise such materials and act as collaborators and co-producers of curriculum is.

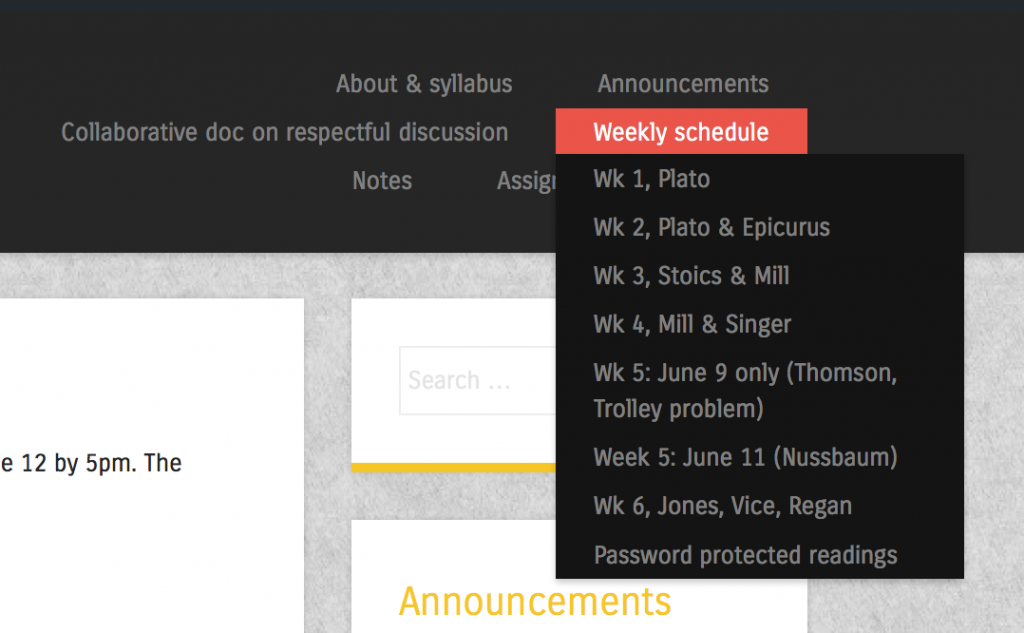

Tom Woodward expands on this view of open pedagogy to refer to “a general philosophy of openness (and connection) in all elements of the pedagogical process,” where “[o]pen is a purposeful path towards connection and community” (Grush, 2013; italics in original). Thus, open pedagogy can also include open assignments, which allow students to shape how they will show evidence of learning (or even create assignments for other students to do); open course planning, in which one invites comments and contributions from others when planning a course; and what Woodward calls “open products,” where students publish their work “for an audience greater than their instructor. … Their work, being open, has the potential to be used for something larger than the course itself and to be part of a larger global conversation” (Grush, 2013).

Asking students to create open products, to do work openly and publicly and thereby contribute to knowledge production both inside and beyond the course, is also part of a pedagogical model that Neary and Winn (2009) call “the student as producer.” Contrasting with the idea of the student as a “consumer” of knowledge transmitted by an expert, and higher education as guided by market forces for the sake of students’ future employability, the student as producer model can be defined briefly as: “undergraduate students working collaboratively with academics to create work of social importance that is full of academic content and value, while at the same time reinvigorating the university beyond the logic of market economics” (Neary and Winn, 2009, p. 193). The student as producer approach “aims to radically democratize the process of knowledge production” (Neary and Winn, 2009, p. 201). Bruff (2013), citing Bass and Elmendorf (n.d.), emphasizes openness in the student as producer model, by arguing for the importance of students sharing their work with “authentic audiences,” people beyond just the instructor who can benefit from what they are producing. In addition, Bruff (2013) lists two other elements of his view of the student as producer model: students work on open-ended questions or problems, ones that don’t yet have a solution (rather than only working to get the “right” solution to a problem), and students have some autonomy in choosing and carrying out projects.

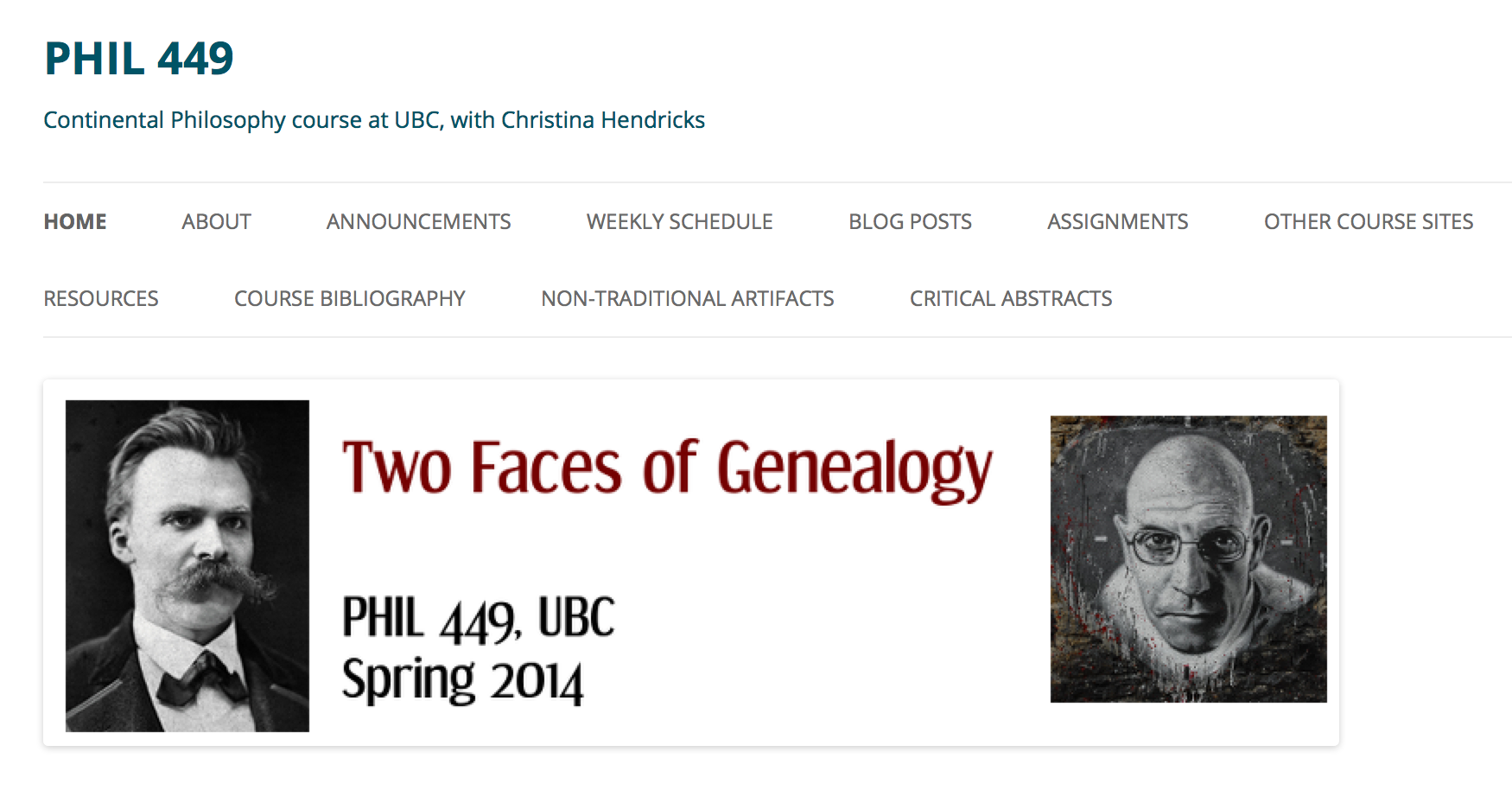

I am here linking the student as producer model with open pedagogy as discussed above, because I think there is significant overlap; I refer to all of these here as “open pedagogy.” Examples of open pedagogy include activities from asking students to make public blog posts (or posts that are at least shared with the rest of the class, even if they are not public), having students create websites or wikis that showcase a research project they have completed, encouraging students to revise OER and re-share them for other students, teachers and the public, to opening one’s classroom activities to participation by those not officially registered in the course (such as by having discussions on social media, opening up presentations by doing them on webinars, and more).

In my work in open education, I have used, created and shared open educational resources, and I have also engaged in various activities I am putting under the general label of open pedagogy.

[In the rest of the application I discuss my open educational activities…]

——————————————————–

[1] Many MOOCs currently are offered through central organizations such as EdX (https://www.edx.org/), Coursera (https://www.coursera.org/), Future Learn (https://www.futurelearn.com/), Iversity (https://iversity.org/), and UnX (courses offered in Spanish and Portuguese) (http://www.redunx.org/web/aprende/cursos). But there are also institutions of higher education that offer their own MOOCs on their own platforms, without connecting to one of these kinds of organizations.

[2] For example, the Coursera terms of use say: “You may download material from the Sites only for your own personal, non-commercial use. You may not otherwise copy, reproduce, retransmit, distribute, publish, commercially exploit or otherwise transfer any material, nor may you modify or create derivatives works of the material.” (Coursera, 2014).

[3] Creative Commons licenses provide a range of choices depending on how one wants to share one’s work (e.g., one can restrict the work to non-commercial uses, one can insist that any new works made from the original be shared also with an open license, or one can allow others to reuse the work but not allow any revisions). Finally, Creative Commons has a public domain license by which one can signal that they are releasing their work into the public domain, free to use, revise, redistribute without restriction on how and for what purpose, and without the requirement that the original creator be attributed. See Creative Commons, “About the licenses” for more: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/.

Works Cited

Bass, R. and Elmendorf, H. (n.d.). Social pedagogies: Teagle Foundation white paper. Retrieved from https://blogs.commons.georgetown.edu/bassr/social-pedagogies/

Bruff, D. (2013, September 3). Students as Producers: An Introduction [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://cft.vanderbilt.edu/2013/09/students-as-producers-an-introduction/

The Cape Town Open Education Declaration. (2007). Read the Declaration. Retrieved from http://www.capetowndeclaration.org/read-the-declaration

Coursera. (2014). Terms of Use. Retrieved from https://www.coursera.org/about/terms

Ehlers, U.-D. (2011). Extending the Territory: From Open Educational Resources to Open Educational Practices. Journal of Open, Flexible and Distance Learning, 15(2), 1–10.

Grush, M. (2013, November 12). Open Pedagogy: Connection, Community, and Transparency–A Q&A with Tom Woodward. Retrieved February 15, 2015, from http://campustechnology.com/articles/2014/11/12/open-pedagogy-connection-community-and-transparency.aspx

Hodgkinson-Williams, C., & Gray, E. (2009). Degrees of openness: The emergence of Open Educational Resources at the University of Cape Town. International Journal of Education and Development Using Information and Communication Technology, 5(5), 101–116. Retrieved from http://ijedict.dec.uwi.edu/viewarticle.php?id=864

Neary, M., & Winn, J. (2009). The student as producer: reinventing the student experience in higher education. In The Future of Higher Education: Policy, Pedagogy and the Student Experience (pp. 192–210). London, UK: Continuum International Publishing Group. Retrieved from http://eprints.lincoln.ac.uk/1675/

Open Knowledge Foundation. (n.d.). The Open Definition. Retrieved from http://opendefinition.org/od/

Wiley, D. (n.d.). The open content definition. Retrieved from http://opencontent.org/definition/

Wiley, D. (2013, October 21). What is Open Pedagogy? [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://opencontent.org/blog/archives/2975

William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. (n.d.). Open Educational Resources. Retrieved from http://www.hewlett.org/programs/education/open-educational-resources