Hey, there are some kinda nifty animated GIFs from an episode of The Twilight Zone over on a Tumblr.

Here’s the first two, and here’s a post where one of those is redone in an interesting way.

Teaching & Learning, and SoTL, in Philosophy

An introduction for #ds106zone, the Summer 2013 version of #ds106 (or rather, winter for me here in Australia).

Creating the video itself was fairly simple–I did it in Apple iMovie on my Mac (recorded and edited there, and added the titles too). Then I decided to use Mozilla Popcorn to add some links, and thought of a couple of other words to put on there as well…and it drove me absolutely bonkers.

I messed around with the timing of the links and the text that pops up at various times, and I would get it just right and then the next time I played it the timing would be off. So I’d fix it and it would seem fine, and then I’d play it and the timing would work fine…until the next time I played it. I honestly never knew when the damn things were going to pop up. And in the video below, some are WAY off. But I can’t seem to fix it, no matter what I do. [Update the next day: now they seem to be timed pretty well when I play it.] Trick: use the green “play” button at the bottom…I think that helps get the timing right (rather than the grey play button on the original Vimeo video.

I’ve used Popcorn before and didn’t have this much trouble…not sure what is going on.

At any rate, next time I might just use the stupid YouTube video editor to add links. Might work better. But I expect I’ll learn more in #ds106 of better ways to do what I’m trying to do.

Maybe viewing it from the original link will work better than the embedded version? The original looked okay when I viewed it the last time, but who knows. Here’s the original video on Vimeo, without the links and text added through Popcorn.

Later update: Realized one of my added pop-up statements was wrong; tried to change it over at Mozilla popcorn, and it seemed to work…but when I go to the link from outside the program, it’s not saved. IT JUST WON’T SAVE the new version, even though it says it has. I cannot believe how much time I’ve spent trying to get this to work. I give up.

I DID NOT PRONOUNCE COGDOG’S NAME INCORRECTLY, OKAY? Dammit.

Even later update: Okay, seems to have finally saved, so the below is actually the corrected version. I am so done with Popcorn right now.

Gah.

Recently I contrasted ds106 with a course in statistics from Udacity, as part of my participation in a course on Open Education from the Open University. I got very frustrated writing that post because I felt constrained by the script, by the instructions. It wasn’t that I had other things to say that didn’t fit the script; it was more that following the explicit instructions seemed to keep me from thinking of other things to say. I was busy saying what I was supposed to, and therefore didn’t leave myself mental space to consider much of anything else.

Usually I only write blog posts when I have something I want to reflect on, to share with others, to get feedback about. It’s self-generated, and I care about what I’m doing. That hasn’t been the case for many of the posts I’ve done for the Open Education course, and it has just felt far too forced and unmeaningful.

I decided to stop.

That’s IT! Just wrote most boring blog post ever b/c following script. Never again. Need to cleanse with some #ds106 #dailycreate

— Christina Hendricks (@clhendricksbc) April 25, 2013

Apparently the post was actually useful to some, as some Twitter conversations & retweets indicated, but it still felt dull to me because I wasn’t the one deciding what to write, or whether to write at all. Okay, yes, ultimately I was the one, of course, since I didn’t need to (a) do this particular activity for the course, or (b) do it in the scripted way, or (c) join the course at all in the first place. So yes, I decided. But my point is more subtle. And it affects how I approach face-to-face teaching as well.

In my previous post, I listed some of the major differences between ETMOOC and the OU course, and talked a bit about why I preferred the former. Here I want to focus on one particular downside to the OU course.

The directed assignment

There is probably a better word or phrase for this–I just mean an assignment or activity in which one is told exactly what to do. This is what we had, each week, several times a week, in the OU course. It is not what we had in ETMOOC.

In ETMOOC we had a few suggestions here and there for blog topics, things one could write about if one wanted. During some of the bimonthly topics there were lists of activities we might do if we wished, including reading/watching outside materials and writing about them. But there was a strong emphasis that one should choose one or just a few of these, or none at all (see, e.g., the post for the digital storytelling topic in ETMOOC). The activities were clearly suggestions, and participants could (and many did) blog about anything that caught their attention and interest in relation to the topics at hand, whether from the suggested activities, the presentations, the Twitter chats, or others’ blog posts.

My experience with the OU course was much different. The activities were written as directives rather than suggestions. Here, for example, is an activity about “connectivism” that I decided not to do (other examples of directions can be found by clicking on the #h817open tag to the right). I am going to blog about connectivism and how it informs the structure of cMOOCs, as it’s something I’m interested in, but that’s just the point. The way the activities in the course are written, one gets the strong message that directions should be followed. The rhetoric is clear. You may be interested in writing about something else, but then you’re not participating in the course.

Sometimes I followed the instructions; sometimes not. My choice, yes, but something else happens too.

Follow the path, CC-BY licensed flickr photo shared by Miguel Mendez

There could easily be, and for me at times there was, a strong enough feeling that I ought to follow directions that, well, I did. It’s just a sense that that’s what you do in a “course.” And the fact that this was an “open boundary” course–meaning it had students officially registered for credit as well as outside participants–probably contributed to it having a more traditional structure. But that structure suggested, implicitly, that one should do what the instructor says.

Incidentally, this was another difference from ETMOOC–in the OU course, there was clearly one instructor in the “expert” or “authority” role. In ETMOOC there were many people involved in both planning and facilitating, and unless they were giving one of the synchronous presentations, they acted just like every other participant in the course. The information about each week’s topic seemed to come from some anonymous source, without a clear authorial voice, even though it had a list of people at the end who were involved in working on that topic. It felt less hierarchical, more like a collective group of people learning together than a set of instructors vs. learners.

I’m not concerned about having specific, assigned readings, videos, or other materials; some of those for the OU course I found very helpful, and when one is faced with something unfamiliar, having a few common guideposts on the way is helpful when learning with others. What led me to disengage was being explicitly directed as to what to do with those materials, exactly what to write about. And even though I knew that was optional, the rhetorical thrust of both the wording and the structure of the course indicated otherwise.

I had a bit of a discussion with Inger-Marie Christensen in comments on one of her blog posts, here, about this issue. She rightly pointed out the danger of just skipping things in a MOOC that don’t seem immediately interesting to you, and I agree. I also see that by following directions I might end up finding new things that I’m interested in, engaged with, that I might not otherwise.

Still, I think that a balance can be struck: encouragement to at least engage with most or all of the topics, read or watch at least one or two things, and then choose from a variety of suggested topics to write about or activities to do (while also providing freedom to do something else related if one chooses). I think the value of greater engagement and more meaningful work by participants by offering such flexibility can outweigh the loss of perhaps missing some aspects of a topic.

Face-to-face courses

I felt this way earlier in the OU course, but continued on for awhile anyway:

When blog prompts for a MOOC are structured & rigid, my blog posts are structured, cold and boring. BORING! And still not finished on time. — Christina Hendricks (@clhendricksbc) April 4, 2013

And another implication struck me then, too:

Re: my last tweet—ok, now I get my students. Wow.

— Christina Hendricks (@clhendricksbc) April 4, 2013

@clhendricksbc Yeah if we don’t like doing it why would they?

— Karen Young (@karenatsharon) April 4, 2013

@karenatsharon Exactly. And yet I’m just seeing this now. That’s kinda sad, but at least I’m getting it at all.

— Christina Hendricks (@clhendricksbc) April 4, 2013

@clhendricksbc It helps when you’re an elementary teacher. As soon as the kids go ewww you know you’ve picked a stinker for an assignment! — Karen Young (@karenatsharon) April 4, 2013

But in Uni the students either just do what you ask or drop the course. And suddenly it’s hitting me that when I provide clear, detailed instructions on what to write for essays, my students may respond the way I did. How did I not see this before?

I often give very detailed essay assignments, saying exactly what should be written about. I have thought I’m doing students a favour by providing clear directives. And for some, that’s probably the case. But I’m also:

Now, I actually do give students in third- and fourth-year courses more freedom, but I tend to be more directive in first- and second-year courses. And I’m wondering if I can strike more of a balance between specificity and flexibility. I realize that people new to philosophy can use clear guidance on how to write philosophy essays well, and sometimes that could mean telling them exactly what to write about. But does it have to? At the very least, I could make it clearer that the provided essay topics are suggestions rather than directives, and emphasize that there is room to experiment.

I could, thereby, open up students to the significant possibility of writing essays that are deeply problematic because I gave them the freedom to fail. But if I also give them detailed feedback and the chance to revise without penalty, then, well, that seems to me a good way to learn. And maybe they’ll be excited to do so in the process. Okay, at least some of them.

The bigger issue

But this doesn’t address the problem noted above: even if one says, explicitly, that directives are optional, one’s other words and course structure may indicate that, after all, they really should be followed. And/or, the learning experience for many has for so long been such that when the instructor gives suggestions for what to do, many students may do that rather than come up with something on their own, because after all, the instructor is in the position of authority/expertise.

Even in ETMOOC, I recall several participants expressing how they felt “behind,” and needed to “catch up”; some even said they dropped out because they felt so behind. The message of flexibility may not have gotten through.

So I am left with two problems for my face-to-face teaching:

1. How to balance promoting flexibility and creativity, and thereby hopefully greater engagement, with the danger of learners only focusing on what they want and not going beyond their comfort zones (hmmm…seems to me I’ve visited this issue before).

2. Once I solve problem number 1, how to communicate that flexibility really means…flexibility?

So far in 2013, while on sabbatical, I’ve actively participated in two MOOCs (Massive, Open, Online Courses): the OU course on Open Education, and ETMOOC (Educational Technology and Media MOOC). The latter was one of the best educational and professional development experiences I have ever had. The former…well…was just okay. Not bad, but not transformative like ETMOOC was.

I want to use this blog post to try to figure out why this might have been the case, and in the next one I’ll focus in on one particular difference and discuss it in more depth.

I don’t think it was just the most obvious difference, that the OU course was an “open boundary” course, meaning it was a face-to-face course that invited outside participants as well, and ETMOOC was not–though ultimately, this may have been an important part of why the two differed so much.

A heated discussion, CC-BY licensed flickr photo shared by ktylerconk

1. Synchronous presentations/discussions

ETMOOC had 1-2 synchronous presentations weekly, some by the “co-conspirators” (the group that planned and facilitated the course), and some by people outside the course. These were mostly held on a platform that allowed interactivity between the presenter and participants, including a whiteboard that participants could write on synchronously, and a backchannel chat that presenters often watched and responded to.

Instead of synchronous presentations, the OU course had assigned readings and/or videos for each week. ETMOOC had no such assigned materials, just the synchronous sessions. These are somewhat similar, though of course the presentations get you a sense of being more connected to the presenter than does reading a static text or video from them. There is at least the chance of asking live questions.

The OU course had one synchronous presentation and two synchronous discussions–the last one a discussion of how the course went & thoughts for the future. I could only attend one of these because of time zone issues, and there was much less interactivity–the chat was much less active, e.g.

2. Twitter

ETMOOC had a weekly Twitter chat that was, most weeks, very lively. I met numerous people through these chats that I followed/got followers from, and I still interact with them after the course. The Twitter stream for the #etmooc hashtag was quite busy most of the time, and still has a good number of posts on it. The OU course had no synchronous Twitter chat, and most days saw maybe 2-3 tweets on the #h817open hashtag. Few participants used Twitter, and those that did, didn’t use it very much. Mostly they announced their own blog posts/activities for the course, though some shared some outside resources that were relevant.

3. Discussion boards vs. Google + groups

OU had discussion boards where, I imagine, much of the discussion took place (instead, e.g., of being on Twitter). ETMOOC had no discussion boards, only blogs, Twitter, and a Google+ group.

Iwent to the OU boards a couple of times, and remembered that I really don’t like discussion boards. I am still not sure why. Partly because they feel closed even if they are available for anyone to view, and partly because I don’t feel like I’m really connecting to people when all I’m getting are their discussion board posts. Unlike Twitter or Google+, I can’t look at their other posts, their other interests and concerns. I stopped looking at the boards after the first week or so.

Fortunately, some of the members of the OU group set up their own Google+ group, so I did most of my discussion on there (and on others’ blogs). There was a small group of active participants on G+ that frequently commented on each others’ blogs, much smaller than the ETMOOC Google + group.

Linked, CC-BY licensed flickr photo shared by cali4beach

4. Building connections

ETMOOC started off with some presentations and discussions on the sorts of activities needed to become a more connected learner (unsurprisingly, as this was a connectivist MOOC), such as introductions to Twitter, to social curation, and to blogging (one of the two blogging sessions stressed the importance of commenting on others’ blogs, how to do it well, etc.) (see the archive of presentations here). Many of us are still connecting after the course has finished–through a blog reading group, through Twitter and G+, and through collaborative projects we developed later.

OU had no such introduction to things that might help us connect with each other–again, unsurprisingly, as it wasn’t really designed as a cMOOC, it seems. There was a blog hub, and there were suggestions in the weekly emails to read some of the blog posts and comment on them, but it wasn’t emphasized nearly as much as in ETMOOC.

I don’t see myself continuing to connect with any people from the OU course; or maybe I will with just a couple. I didn’t really feel linked to them, even though we read and commented on each others’ blogs a bit. I think the lack of synchronous sessions, including Twitter chats, contributed to this–even in the ETMOOC presentations we talked with each other over the backchannel chat. Of course, things might have been different if I had participated in the online discussion forums in the OU course; but I still think those are not a very good method for connecting with others, for reasons noted above.

5. Learning objectives

The OU course had explicit learning objectives/outcomes for the course as a whole, and for each topic in the course. ETMOOC, by contrast, explicitly did not–see this set of Tweets for a discussion about why. The quick answer is that ETMOOC was designed to be a space in which participants could formulate their own goals and do what they felt necessary to meet them.

6. Dipping vs. completing

ETMOOC had about five topics, each of which ran for two weeks. They were more or less separate in that you didn’t have to have gone through the earlier ones to participate in the later ones. There was an explicit message being given out by the co-conspirators, picked up and resent by participants, that it was perfectly fine to start anytime and drop out whenever one needed/wanted, coming back later if desired. There was no “getting behind” in ETMOOC–that was the message we kept hearing and telling to each other. And after awhile, it worked, at least for me; I missed a few synchronous sessions and didn’t feel pressure to go back and watch them. I just moved on to things I was more interested in.

The OU course seemed more a “course” in the sense of suggesting, implicitly, through its structure, that it was something one should “complete–one should start at the beginning and go through all the sections, in order. Some of the later activities built directly on the earlier ones. Now, clearly, this makes sense in the context of having a set of course objectives that are the same for all–participants can’t meet those if there isn’t a series of things to read/watch/do to get to the point where they can fulfill them.

So, clearly, two very different MOOCs, doing different things, for different purposes. Obviously, for some people in some contexts and for some purposes, each one is going to have upsides and downsides. In the next post I focus on one particular downside, for me, of the OU course (though, as you can tell from my tone in the above list, I found ETMOOC more engaging). I also appreciated the flexibility, which the next post addresses.

ETMOOC is finishing up next week, and I’m about to leave town and be very sleep deprived for the next 3-4 days or so, so this is kind of my last hurrah for ETMOOC. I was trying to think about how/why my experience in it has been so important, so much so that I’m very sad it’s nearly over.

Instead of writing my response to that, I decided to try my first vlog–as a final project for ETMOOC, something else I’ve never done before (though I did do a “true story of openness” for Alan Levine).

Not surprisingly, it’s probably too long–just like my blog posts, my articles, and my plans for class meetings.

And I had only a couple of hours today to get it done, so it’s not terribly polished. I have a lot to learn about video editing, such as how to not only edit out portions of the video but also the audio that went with them (I tried to get rid of some “ummm’s” and “so’s,” and the video got deleted but not the audio. Hmph.). And that handmade heart at the beginning and end? Yeah, that should have been a nice title for the video…didn’t have time to do anything but cut one out and write on it.

So this is my love letter to ETMOOC. So sad to see you go.

[P.S. Is it possible to change the “still” shots from videos (such as the one below) so they aren’t those horribly strange facial expressions that come up when you’re in the middle of saying something?]

During one of the Twitter chats for the ETMOOC topic on “The Open Movement – Open Access, OERs & Future of Ed,” Pat Lockley Tweeted this:

#etmchat – most of github is now unlicensed, I think we are moving into a post-license world

— patlockley (@patlockley) March 7, 2013

We were talking about sharing our educational or other work, why some people find this difficult, the difference between “open access” and things being open in a wider sense, and more.

During the chat Pat’s Tweet kind of just went past me, but as I went back to the #etmchat Tweets for that day to add some to my Storify board on my ETMOOC experience, I came across it again and became curious as to what he meant. Thus started a fairly long conversation about copyright, licenses, public domain, and more. You can see it all here.

There’s a lot I’d like to think about further in this conversation, but what is really standing out for me at the moment is this:

@patlockley Definitely better understood. Now wondering why ppl might want to be attributed. Why do I have CC-BY on my blog? Why do I care?

— Christina Hendricks (@clhendricksbc) March 11, 2013

@patlockley Beyond pragmatic reason (if I can show influence of my work I have better chance of promotion), I wonder if there’s something… — Christina Hendricks (@clhendricksbc) March 11, 2013

@patlockley …about wanting to just be acknowledged by others as an author/creator that’s important. Ego? — Christina Hendricks (@clhendricksbc) March 11, 2013

@clhendricksbc ego perhaps a step far – nice to know people like your stuff, but then is attribution enough or explicit recognition

— patlockley (@patlockley) March 11, 2013

Why am I using a CC-BY license on my work? Why do I care if I’m attributed when someone uses something from my blog, or some “open educational resource” I create? Pat brought up an important point:

@clhendricksbc yes, but you ask if whether public domain is not a better option

— patlockley (@patlockley) March 11, 2013

@patlockley So then no need for attribution or anything. Easy, but why might it be better than CC-BY, e.g.? I mean, philosophically.

— Christina Hendricks (@clhendricksbc) March 11, 2013

@clhendricksbc yes, why make it open – to be reused or to be attributed for reuse. Public domain is more understood as a term?

— patlockley (@patlockley) March 11, 2013

Why not make one’s work public domain instead of using something like CC-BY? In the current legal climate, apparently it’s rather complicated: some places, like Canada and the U.S. (and probably other places too–I haven’t done enough research to list them), grant copyright simply through creating a work, and this may not actually be easy (or possible?) to give up (see, e.g., re: the U.S., Wikipedia on granting work into the public domain, and this post from the Public Domain Sherpa, and the last section of this page from Copyfree). One can, though, try to state as clearly as possible that one gives up all copyright and related rights to whatever extent allowed by law, and if not allowed, to give a license to anyone to use the work however they wish, without requirement of attribution. That’s what Creative Commons CC0 is meant to do. Copyfree has a list of various licenses that conform to their standard of “free use,” “free distribution,” free modification and derivation,” “free combination” and “universal application,” and CC0 is one of them (as is the Nietzsche public license, which is rather a personal favourite).

So, getting back to the original question and modifying it a bit: why not just use CC0 or something similar, thus releasing one’s work for any use by anyone, without attribution? Why care about attribution?

As Pat Lockley noted, it would be good to know that others find my work useful and that they reuse, repurpose and/or rework it. This would be helpful, if for no other reason than to validate for yourself what you’re doing. It could help you do more of it, perhaps. Knowing this would probably also be a way to improve one’s work through finding out what others have done with it. Not to mention it could be a way to potentially connect with others, which might even lead to collaborations.

In my own situation, on a pragmatic level, if I could discover and document how others have used my work, this could provide evidence that what I am doing has influence in the wider educational community, which might be one of several ways to support a claim of “educational leadership” or “distinction in the field of teaching and learning” for the new Professor of Teaching rank at UBC.

So yes, there are plenty of good reasons to be able to know what others are doing with your work.

But all of this requires what is NOT happening with CC-BY (and possibly not with other licenses…I haven’t done enough research to specify): notifying the attributed person that their work is being reused. If another blog links to your blog, you may get a pingback (maybe not; depends on the settings of your blog and the other blog, I think). And it’s a good practice to let other people know when you’ve used their work, if there’s an easy way to do it (such as leaving a comment on a photo posted on Flickr). I try to do that, but too often I forget (I’m working on this).

As noted towards the end of the Storified conversation with Pat, what’s missing, in order to get the benefits noted above, is some systematic way to notify people as to how you’ve used their work. I don’t even know how such a thing could work–the technological hurdles seem huge–but theoretically, it seems a good idea. Now, like any such things, one wouldn’t have to choose such a license (an attribution + notification license?), but for some it would provide a useful way to not just be attributed, but to know what uses their work is being put to. Perhaps it is too difficult/too much of a hassle to bother with. But it’s an intriguing idea.

Of course, there are good arguments for making work as free as possible, without restrictions on what you have to do once you’ve accessed it–like attributing the author/creator, or telling him/her what you’re doing with it. So I’m undecided whether I, personally, would want to require more of the people using my work than just attribution. I might not even recommend this to others. But some might want to do it, and it could be useful.

But until and unless something like this happens, I’m back to my original question: Why do I care about attribution? If, for the most part, I won’t get the above benefits, what am I getting out of knowing that perhaps, somewhere out there, is a piece of work with my name attached?

One might think that it’s kind of like citation in academia; except again, citations are tracked whereas use of my CC-BY work (unless it’s a publication) is not. So really, it’s just a sense that other people know I created something. Why should I care about this?

Add to this the point that much of my work is not, perhaps, really “mine” in a deep sense because it is a culmination of so many other influences, work by so many other people that I have read or otherwise interacted with, and the question becomes even more pressing.

Okay, maybe it will come back to me at some point; maybe I’ll discover my work being used somewhere with my name, and then I can realize some of the good things noted previously. But maybe not (and perhaps most likely not). Or perhaps someone will find something with my name on it and decide to connect with me–thus leading to a connection through effort on someone else’s part rather than mine. These things might happen, but is that enough to require attribution for my work? I’m not yet sure.

I don’t have an answer, and you can’t answer for me of course, but maybe you have some ideas on why asking others to attribute one’s work might be a good idea, rather than just letting it go free into the wild. I’m thinking not so much for people who have to rely on their work to make a living, to make money off of it, but for people like me who are getting a salary from a university and could just share their blog writings, their photos, their OERs for free and without restrictions.

Help me out here?

Image credit: “Attribution,” flickr photo (CC-BY) shared by fotogail

“Panopticon,” cc licensed ( BY ) flickr photo shared by chad_k

“Panopticon,” cc licensed ( BY ) flickr photo shared by chad_k

A year or two ago a student came into my office and told me about some podcasts he had been listening to, which consisted of some lectures by a well-known philosopher as part of one of his university courses. The student then asked me why I didn’t put my lectures out on podcasts, or make them public in some other way.

I don’t remember what I said. But I do remember what I felt: apprehension. And some fear. I couldn’t imagine, at the time, doing such a thing.

Now I can, and largely through my experience in ETMOOC I’ve become very interested in the idea of “openness” in education and want to start doing some of this myself. Of course, “open” means different things in different contexts (here’s a nice post explaining some of them, and here’s an even larger list of various “opens”) , but I’m considering things such as posting and licensing many of my course materials for re-use, as well as possibly opening up a course to outside participants the way Bryan Jackson did with his high school Philosophy course.

The value of open education

There are plenty of good things about opening up your teaching and learning materials, space, interactions, etc. Bryan Jackson explains something good that happened as a result of having an open Philosophy course, in this video. Barbara Ganley had an interesting experience from a writing assignment in her class posted publicly on a blog (see “A Writing Assignment Gets Personal,” on this site).

David Wiley, in a presentation on open education called “Openness, Disaggregation, and the Future of Education” (the keynote for the 2009 Penn State Symposium for Teaching and Learning) gave several examples of things he had done recently in his courses to make them more open. Among them:

My experiences in ETMOOC are good evidence as well: I now have a much wider network of people to talk to about teaching and learning, and educational technology, because this course is open to anyone who wants to join and participate. I have more comments on my blog, many more twitter interactions, more people to help answer questions (I just ask the Twittersphere and answers come quickly), more links to helpful resources for my own thinking and teaching and learning, and more.

These are just a few examples of good things that can come from opening up education. I’m certain there are many more.

In addition, ETMOOC-ers said some good things about the value of openness in a recent Twitter chat:

@courosa A1 I think people adding to and sharing others work INCREASES the value of the work.Reach more people #etmchat

— Debbie Vane (@debvane) March 7, 2013

@courosa The work then becomes our work instead of owned&controlled by 1person Collective work: collaborate not compete#etmchat

— lisa domeier (@librarymall) March 7, 2013

q2) One strength of the open movement is that it becomes a powerful tool useful in promoting creative collaboration a la #etmooc #etmchat

— Paul Signorelli (@trainersleaders) March 7, 2013

@kooner_j Good point – I’m quite sure my work has improved because I know that it will be read beyond the classroom. #etmchat

—Alec Couros (@courosa) March 7, 2013

I can see many benefits to opening up my teaching and learning more than I’m already doing, and I expect there are more that I can’t even currently imagine.

So was I reticent before, when my student asked about podcasting my classes, only because I didn’t see these benefits then? I don’t think so.

Fear and Openness

There are many ways of making one’s courses more “open,” including just posting one’s course materials for others to see (e.g., written materials, digital presentations, video or audio of lectures); giving the materials a Creative Commons license that allows others to reuse, repurpose, and build on them; live streaming your class meetings publicly; all the way to opening out the course to any participants who want to join (see Alec Couros‘ Social Media & Open Education course as an example, as well as Bryan Jackson’s high school philosophy course noted above). The concerns I bring up below apply to all of these, but mostly to the last two.

The apprehension I felt at the idea of podcasting my lectures wasn’t just the usual fear of being in front of a camera or having one’s voice go out into the wider world; I was a college radio DJ in university and grad school, and am don’t mind speaking into the void with the knowledge that many people (or none) might be listening. Video is still a little tough for me, but I’m quickly getting over that.

It wasn’t just a lack of confidence, a sense that no one would want to listen to my lectures when they have access to those of people who are much more expert than me on the topics they’re discussing (though there was some of that too).

There was something about potentially being watched, being observed, at any time, by anyone; but mostly, by those who could have significant influence over my future. It’s not that I worry my teaching isn’t very good, or that I think bad things would happen if those who can affect my employment see most or all of what I do in class. I actually have (and have had) fantastic colleagues, and every time I’ve had a peer visit a class it has ended up being a very positive experience, complete with helpful advice–much of which I still vividly remember and use.

I think it was partly that in having my courses be “open” it’s as if I could be undergoing a peer review of teaching at any time, all the time.

Which means, of course, (being a Foucault scholar) that I thought of Foucault.

Panopticism

Panopticon, Jeremy Bentham [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

It’s not just a concern about possibly being observed at any given moment. Nor is it only that there could be a potential danger to this vis-à-vis power relations in one’s place of employment. It’s also that this situation of potentially being observed at any given moment can pressure one to change one’s own behaviour in order to bring it more in line with dominant norms. We police ourselves, rather than having to be policed. There doesn’t even have to be anyone watching for this to happen.

Now, this isn’t always necessarily bad. I agree with Alec Couros’s tweet, above, that knowing others might see my work would spur me to make it as good as possible. Plus, of course, if others saw it and commented, this could help me improve it even more.

But the potential downside is that one might be less likely to try radically new things, to experiment, to risk doing things that don’t fit with dominant views of how education is “done.” Clearly this isn’t true for everyone; there are people doing innovative things openly (e.g., many of the conspirators in ETMOOC)–though even then one usually has a community with its own norms that one is part of.

The issue would be prominent especially for those who don’t have tenured or otherwise semi-permanent positions–it’s often (though not always) in their best pragmatic interest to police themselves not to take too many risks if their work is open, though some risk-taking might be seen as positive.

So one reason some people might not be willing to be more open in their teaching and learning might be because of vulnerability. They could be vulnerable in the sense of not having a stable position, or in the sense of having a particular department or school climate that makes it such that opening their teaching could be dangerous to their position (because their colleagues may not agree with what they’re doing, e.g.).

I am fortunate in that neither of these situations applies to me, but that’s a bit of a luxury, and there are many people who don’t have it.

One more thing

I wonder if making my courses more open, in the sense of recording the sessions, would change how I conduct some of my class meetings. A fair number of them are unscripted, experimental forays into topics through (sometimes haphazard) discussion that may or may not come to a clear end point (usually not). I think of these as part of a work-in-progress, a long-term work in which I and the students are moving towards better understanding of certain issues, questions, arguments, texts. Or at least, different understanding that brings up fruitful, new ways of thinking about and approaching these things, showing further dimensions that were hidden before. This work-in-progress may last for a few weeks or months, a few years, or a lifetime. The courses, for me, are just a very small part of this process. In some ways I like that the class meetings are evanescent, short-lived; they aren’t final products in any sense and aren’t meant to be. I wouldn’t want anyone to watch one or two such meetings and get the sense that what I or anyone else says there represents anything more than a provisional test of a thought or argument. It will always change later.

Somehow, recording one’s course sessions seems to me to be making them more permanent, which goes against the way I think of the meetings. I want them to be memories only, things that change when you revisit them, just as the ideas do.

Of course, these issues exist with writing and publishing too–writing is never permanent, and one’s arguments can change radically over the course of a few years. But writing already seems more stable than a class discussion that takes place orally.

Conclusion?

I don’t have one. I just wanted to explore why I might have been reticent to be open, and why others might be. These thoughts on panopticism and sharing things publicly are anything but new, but they may be factors for some.

As with anything, there are benefits and drawbacks to being open in teaching and learning. I think the benefits, in my own personal situation, outweigh the risks of being open (as well as the concern about “permanency” noted above). But that may not be true for everyone, and it may for reasons other than a desire to keep one’s work to oneself, or out of a lack of confidence.

In the last post I discussed how I have come to learn about the different kinds of MOOCs through my participation in etmooc. I also said that through learning about a new kind of MOOC, the cMOOC or “network-based” MOOC, I was reconsidering my earlier concerns with MOOCs. Might the cMOOC do better for humanities than the xMOOC?

A humanities cMOOC

“Roman Ondák”, cc licensed ( BY ) flickr photo shared by Marc Wathieu

“Roman Ondák”, cc licensed ( BY ) flickr photo shared by Marc Wathieu

I haven’t yet decided whether or not one could do a full humanities course, such as a philosophy course, through a cMOOC structure. Brainstorming a little, though, I suppose that one could have a philosophy course in which:

Would this sort of structure be more likely to allow for teaching and practice of critical thinking, reading and writing skills, as I discussed in my earlier criticism of MOOCs (which was pretty much a criticism of xMOOCs)? I suppose it depends on what is discussed in the presentations, in part. The instructors/facilitators could model critical reading and thinking, through explaining how they are interpreting texts and pointing out potential criticisms with the arguments. They could talk about recognizing, criticizing, and creating arguments so that participants could be encouraged to present their own arguments in blogs as clearly and strongly as possible, as well as offering constructive criticisms of works being read–as well as each others’ arguments (though the latter has to be undertaken carefully, just as it is in a face to face course).

This would involve, effectively, peer feedback on participants’ written work. Rough guidelines for blog posts (at least some of them) could be given, so that in addition to reflective pieces (which are very important!) there could also be some blog posts that are focused on criticizing arguments in the texts, some on creating one’s own arguments about what’s being discussed, etc.

What you wouldn’t be able to do well with this structure are writing assignments in the form of argumentative essays. These take a long time to learn how to do well, and ideally should have more direct instructor/facilitator feedback rather than only peer feedback, in my view. Peer feedback is important too, but could lead to problems being perpetuated if the participants in a peer group share misconceptions.

Another thing you can’t do well with a cMOOC is require that everyone learn and be assessed on a particular set of facts, or content. A cMOOC is better for creating connections between people so that they can pursue their own interests, what they want to focus on. Each person’s path through a cMOOC can be very different. Thus, as noted in my previous post, there is not a common set of learning objectives; rather, participants decide what they want to get out of the course and focus on that.

One would need to have a certain critical mass of dedicated and engaged participants for this to work. If it’s a free and open course, then people will participate when they can, and can flit in and out of the topics as their time and interest allows. That’s fantastic, I think, though if there are few participants that might mean that for some sections of the course little is happening. So having a decent sized participant base is important. (How many? No idea.)

I envision this sort of possibility as a non-credit course for people who want to learn something about philosophy and discuss it with others. Why not give credit? There would have to be more focus on content and/or more formal assessments, I think (at least in the current climate of higher education).

A cMOOC as supplement to an on-campus course

Even if a full cMOOC course in philosophy or another humanities subject may not work, I can see a kind of cMOOC component to philosophy courses, or Arts One. In addition to the campus-based, in-person course, one could have an open course going alongside it. This is what ds106 is like. One could have readings and lectures posted online (or at least, links to buy the books if the readings aren’t readily available online), and then have a platform for students who are off campus to engage in a cMOOC kind of way.

Then, those off campus can participate in the course through their blog posts and discussions/resource sharing on the other platforms, like we do in etmooc. Discussion questions used in class could be posted for all online participants. Students who are on campus could be blogging and tweeting and discussing with others outside the course as well as inside the course.

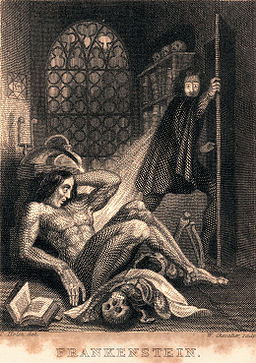

Frontispiece to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1831),by Theodor von Holst [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. One of the texts on Arts One Digital.

Arts One has already started to move in this direction, with a new initiative called Arts One Digital. So far, there are some lectures posted, links to some online versions of texts, twitter feed, and blog posts. This is a work in progress, and we’re still figuring out where it should go. I think extending the Arts One course in the way described above might be a good idea.

Again, the main problem with this idea (beyond the fact that yes, it will require more personnel to design and run the off-campus version of the course) is getting a high number of participants. It won’t work well if there aren’t very many people involved–a critical mass is needed to allow people to find others they want to connect with in smaller groups, to engage in deeper discussions, to help build their own personal learning network.

Looking back at previous concerns with (x)MOOCs

Besides general worried about their ability to help students develop critical skills, I was also concerned in my earlier post with the following:

Can a cMOOC address these concerns?

cMOOCs in humanities–what’s not to love?

What other problems might there be with trying to do a cMOOC in humanities, whether on its own or as a supplement to another course? Or, do you love the idea? Let us know in the comments.

UPDATE: I just found, in that wonderfully synergistic way that etmooc seems to work, this blog post by Joe Dillon, which explains how well a cMOOC like etmooc stacks up to a face to face course. It’s just one example, but it can provoke some further thought on whether a cMOOC for humanities might be a good thing.

cc licensed ( BY ) flickr photo shared by Cikgu Brian

cc licensed ( BY ) flickr photo shared by Cikgu Brian

Last October I posted some criticisms of moocs (massive, open, online courses) in humanities as too massive to really deal well with promoting critical skills in learners. Recent experience has made me change my mind, but it’s going to take two blog posts to explain. This is the first. (The second is here.)

Part of the issue with MOOCs that I expressed in my earlier post was that they were too content-focused, and seemed most conducive to topics in which that content can be machine-assessed (with multiple-choice or other automate-able question/answer formats). I wondered whether critical thinking, reading, writing and discussing skills could really be done well in a MOOC.

The problem is, at the time I wrote that I fell into the common trap of thinking that MOOCs are a monolithic type of entity. I may, perhaps, be forgiven this as most of the press about MOOCs is about the Coursera/EdX/Udacity type (as Alan Levine notes in a blog post–see below). It was only through participating in etmooc, a mooc about educational technology and media, that I found that there are other options.

Not all MOOCs are equal

One way of distinguishing types of MOOCs (at least at the moment…things are always changing) is to break them down into two categories: xMOOC and cMOOC. What do these categories mean? The “c” in cMOOC stands for “connectivist,” but I am not sure what the “x” in xMOOC stands for. [Update May 27, 2013: This Google+ post by Stephen Downes says he started calling them xMOOCs because of the “x” used in things like EdX–which stands for the course being an extension of regular university course offerings].

See here, here and here for some explanations of the differences between cMOOCs and xMOOCs. [update March 17, 2013:] Here’s an even more detailed discussion of the differences, by George Siemens. Lisa M. Lane has come up with three categories for MOOCs, though I’m not familiar enough with the “task-based” MOOCs to really comment on them.

Alan Levine has a thought-provoking blog post on the numerous experiments in open learning (should we call them MOOCs?) that are going on at the moment, and how they are very different from the xMOOC model. The range of possibilities in courses that are open to anyone and everyone is astounding.

The etmooc course I’ve been participating in since Jan. 2013 is in the cMOOC category (or, in Lane’s three categories, it’s a “network-based” mooc). The “connectivist” aspect of it is obvious, as it seems clear that one of the main points of the course is to help people forge connections in order to learn from each other. There is a set of topics, one every two weeks, with presentations by various people working in those fields (all archived here). But the emphasis is not at all on learning content. Rather, participants are encouraged to watch the presentations they are interested in, and then (and mostly) to interact with the rest of the community in various ways: through twitter (#etmooc), a Google+ community, a community-curated list of links on Diigo, and posting and commenting on blogs (syndicated in an etmooc blog hub, though many of us read them on an RSS reader). We also have a weekly twitter chat (#etmchat) in which we discuss issues related to the topic for the week.

There really is no single “place” where the course is; it exists in the discussions we have with each other, the blog posts and digital stories we create and share, the connections we make with others and the conversations (about etmooc and teaching/learning generally, and other things) that we have. I haven’t watched all the presentations, and don’t plan to. Nor is it encouraged. Over and over we are reminded by the course “conspirators” and other participants that etmooc is driven by our own interests (and our own schedules…some have more time than others), and that there is no such thing as being “behind” in etmooc. You dive in when and where you want, and the most important part is to engage in discussion when you can. Blog, comment on others’ blogs, participate in Twitter and G+, or whichever of those you feel you can do.

Among other things, the “about” page for the course says:

Sharing and network participation are essential for the success of all learners in #etmooc. Thus, we’ll be needing you to share your knowledge, to support and encourage others, and to participate in meaningful conversations.

Without the various conversations going on in and around etmooc, there really wouldn’t be a course at all. It exists in our connections and discussion, in the things we share and the comments we make.

In addition to forging connections, etmooc, and other cMOOCs from what I understand, are focused on content creation rather than passive learning of content. In etmooc we contribute to content creation by writing in our own blogs and commenting on those of others. Recently we did a segment on digital storytelling and we created numerous digital stories (see my blog post here for links to a few examples). Right now we are talking about digital literacy and are invited to participate in Mozilla’s work to develop a framework for web literacy (open to anyone to contribute).

Etmooc also requires self-directed learning–participants must choose what to focus on, what to read, what to write about, whether to keep up on twitter and G+ or not, etc. There is no set of course objectives that are decided in advance, as explained in this conversation about learning objectives and cMOOCs on Storify. Rather, as Alec Couros puts it in that Storify conversation, participants are to develop their own learning objectives. Different people will engage with the course for different reasons, pursue different paths. And that’s the point.

The value of a cMOOC

Does it work? Do people learn? All I have at the moment is anecdotal evidence.

I have learned more in the last few weeks in etmooc than I ever did in any other professional development opportunity. It’s because of the connections and discussions: I read others’ blog posts (only a few a week, really; don’t have time for more), comment, and get conversations going. And the same thing happens now on my blog. My twitter lists have expanded widely, and I am getting so many links to articles, blog posts and other resources that are useful for topics I’m interested in.

I agree with Michelle Franz, though I’d say it’s not just twitter I’m learning from in etmooc:

@clhendricksbc Isn’t that the best? I often come to twitter for speedy feedback and assistance. #etmchat

— Michelle Franz (@lrndeveloper) February 14, 2013

@coachk No question!I’m learning more here than I am anywhere else @clhendricksbc #etmchat

— Michelle Franz (@lrndeveloper) February 14, 2013

See also Paul Signorelli’s mid-term reflections on etmooc, where he gives this list of what he has done and learned so far (among other things):

I have become an active part of a newly formed, dynamic, worldwide community of learners; continue to have direct contact with some of the prime movers in the development of MOOCs; had several transformative learning experiences that will serve me well as a trainer-teacher-learner involved in onsite and online learning; and have learned, experientially, how to use several online tools I hadn’t explored four weeks ago.

MOOCs and feedback, interaction

Ted Curran notes in a recent article (found via @jackiegerstein) that MOOCs–or rather, xMOOCs–are “the internet-scale version” of huge introductory courses at large universities with hundreds of students: “massive, impersonal, and uninspiring exercises.” He notes that this model works well if you want to save money (more students, fewer faculty), but it doesn’t work very well pedagogically. What is needed for both the online and in-person teaching and learning platforms, according to Curran, is more emphasis on faculty interaction with students: “personalized timely feedback and frequent interaction with the teacher is more important to student success than the quality of lecturer, the quality of the textbooks, or the use of technology in courses” (emphasis in original). What MOOCs, and online learning in general, can do is to allow faculty

to automate the less effective activities (lecturing, exams, grading) so they can spend more time interacting with students (discussions, online office hours, targeted interventions when students fail assignments.) In short, online teaching tools let teachers spend more time on students and less time regurgitating content.

I agree that faculty/student interaction in courses can be important; it’s one of the most-cited things that students in Arts One said in a recent survey that they valued about the course. But realistically, is this possible in a MOOC that has thousands of participants? How many faculty can actually interact in a meaningful way with students in a course whose enrollment is upwards of 10,000 students or more?

Enter the cMOOC.

Must the interaction that is necessary to student success come from the instructor? Why not set up and foster a space in which interaction is encouraged amongst participants–indeed, where interaction and discussion are as much of (or more of) the focus as content delivery?

I don’t think the discussion boards on most or all xMOOC courses are enough. Discussion boards are limited as a technology: for example, I think blogs are better for posting lengthy reflections, including links and photos/videos, etc. Following blogs and Twitter feeds also promotes more lasting connections to foster learning after the course is finished. Encouraging participants to blog, comment on blogs, and interact in other ways such as Twitter and Google+ (or similar) has, in my experience with etmooc, worked very well.

The experience is still huge–there are far too many blog posts, tweets, G+ posts to follow. But the conspirators and participants are constantly reminding each other that keeping up with it all is not the point. Again, diving in where and when you want is. That, and creating smaller groups organically, through creating connections–deciding which blogs and twitter accounts to follow regularly, for example. Or creating your own smaller group within the larger group, with its own wiki, as another example.

In etmooc the “conspirators” tweet regularly, join in on some discussions in G+, comment on a few blogs here and there, but they don’t even try to interact with everyone. Instead, they have managed to create a space where participants engage mostly with each other.

Now, a purely connectivist mooc won’t work for all purposes; I’m not arguing for replacing xMOOCs with cMOOCs entirely. After all, in some disciplines there is a certain amount of content that simply must be grasped before one can really engage in meaningful discussions with others about the field. Further, for participants to thrive in a cMOOC, they have to be self-directed learners, as noted above, and not everyone is comfortable with this sort of learning.

But why couldn’t xMOOCs take some ideas from the successes of cMOOCs and incorporate more connectivist principles and practices alongside the traditional methods of learning they tend to use?

MOOCs and the media

Alan Levine points out, in the post linked above, that in mainstream media outlets you won’t hear about many of the “experiments in open courses” that some cMOOCs could be called (including etmooc). While drafting the first part of this post I was also engaging in a Twitter conversation with Rolin Moe (@RMoeJo) about how the hype about MOOCs in the media focuses on one type of MOOC only, even though there are at least two. As he noted, the “connectivist” MOOCs tend to be popular amongst educators, academics, and a few others, and they aren’t winning the PR battle.

@clhendricksbc at present it’s a very limited market of academics with no resource to wage a PR battle. Edu doesn’t explain itself well

— Rolin Moe (@RMoeJo) February 21, 2013

The other problem, as we discussed in our twitter conversation, is that cMOOCs are often run by volunteers, because they believe in open learning, and there isn’t much in the way of trying to monetize the efforts. That doesn’t make for interesting news, apparently.

@clhendricksbc learning happens best when social, contextual and informal. Too bad that doesn’t make for profit margins. Great convo, thanks

— Rolin Moe (@RMoeJo) February 21, 2013

A different name?

Since mainstream media has hijacked “MOOC” to mean xMOOC, perhaps it’s time to call the cMOOC something else? Which is ironic, since apparently the whole idea of MOOCs started with cMOOCs (see “connectivist MOOCs” here).

Nevertheless, would a new name help to avoid the confusion? Or is it enough to try to push the xMOOC vs cMOOC distinction?

*** Update March 14, 2013 *****

I just found this blog post by David Kernohan that points to a third option: open boundary courses, in which an on-campus course is opened to outside participants (usually not for credit). It seems to me the “open boundary” courses could be either more like cMOOCs or more like xMOOCs in structure.

For anyone interested in rhizomatic learning, as discussed in my earlier blog posts (here, and here), you might also be interested in the following.

I recently came across this glossary entry for “rhizome,” via a tweet by George (@reticulatrix). It is from a Theories of Media Keywords glossary, which appears to have been created by students in a course from 2004. I found this discussion of rhizomes extremely clear and grounded in theory. Especially helpful is the contrast between rhizomatic models and “tree” models.

In addition, through a comment on one of my blog posts, I found this blog, by Keith Hamon, called Communications and Society. It’s subtitled, “A blog to support Keith Hamon’s explorations of the rhizome,” and there are many, many posts there about rhizomatic learning. He discusses numerous theorists whose views are relevant to this topic. I plan to spend some serious time exploring Keith’s posts. He has continued the conversation started on my blog over at his, and he recently joined etmooc. I look forward to learning more with him!

Finally (though this does not exhaust the resources out there, I’m sure), I found this article by Tanya Sasser over at Hybrid Pedagogy. In this article, entitled “Bring Your Own Disruption: Rhizomatic Learning in the Composition Class,” Sasser argues for a rhizomatic learning approach to first year composition courses. It’s a good example of how to apply rhizomatic learning to a writing course. I have to think about it more carefully, but I plan to comment on this article soon. I am in agreement with the basic idea, but still am a little hesitant. Probably that’s because I’ve been fully immersed in, and convinced by, the idea of using rubrics and step-by-step learning for teaching writing. Still, I’m questioning at least the rubrics part–see this post.

Do you have any other rhizomatic learning resources you’d like to share? Please post them in the comments!