As noted in an earlier post, I have submitted some proposals for conference presentations on researching the effectiveness of connectivist MOOCs, or cMOOCs (see another one of my earlier posts for what a cMOOC is). I am using this post (and one or two later ones) to try to work through how one might go about doing so, and the problems I’ve considered only in a somewhat general way previously. I need to think things through by writing, so why not do that in the open?

I had wanted to think more carefully about connectivism before moving to some research questions about connectivist MOOCs, but for various reasons I need to get something worked out about possible research questions as soon as I can, so I’ll return to looking at connectivism in later posts.

The general topic I’m interested in (at the moment)

And I mean general. I want to know whether we can determine whether a cMOOC has been “effective” or “successful.” That’s so general as to mean almost nothing.

What might help is some specification of the purposes or goals of offering a particular cMOOC, so one could see if it has been effective in achieving those. This could be taken from any of a number of perspectives, such as:

- If an institution is offering a cMOOC, what is the institution’s purpose in doing so? This is not something I’m terribly interested in at the moment.

- What do those who are designing/planning/facilitating the cMOOC hope to get out if doing so, for themselves? This is also not what I’m particularly interested in for a research project.

- What do those who are designing/planning/facilitating the cMOOC hope participants will get out if it? There are likely some reasons, articulated or not, why the designers thought a cMOOC would be effective for participants in some way, thus they decided to offer a cMOOC at all. This is closer to what I’m interested in, but there’s a complication.

The connectivist MOOC model as implemented so far by people such as Dave Cormier, Alec Couros, Stephen Downes and George Siemens encourages participants to set their own goals and purposes for participation, rather than determining what these are to be for all participants (see, e.g., McAuley, Stewart, Siemens, & Cormier, 2010 (pp. 4-5, 40); see The MOOC Guide for a history of cMOOC-type courses, and lists of more recent connectivist MOOCs here and here). As Stephen Downes puts it:

In the MOOCs we’ve offered, we have said very clearly that you (as a student) define what counts as success. There is no single metric, because people go into the course for many different purposes. That’s why we see many different levels of activity ….

Further, just what a cMOOC will be like, where it goes, what people talk about, depends largely on the participants–even though there are often pre-set topics and speakers in advance, the rest of what happens is mostly up to what is written, discussed, shared amongst the participants. The ETMOOC guide for participants emphasizes this:

What #etmooc eventually becomes, and what it will mean to you, will depend upon the ways in which you participate and the participation and activities of all of its members.

Thus, it’s hard to say in advance what participants might get out of a particular cMOOC, in part because it’s impossible to say in advance what the course will actually be like (beyond the scheduled presentations, which are only one of many parts of a cMOOC).

Some possible directions for research questions

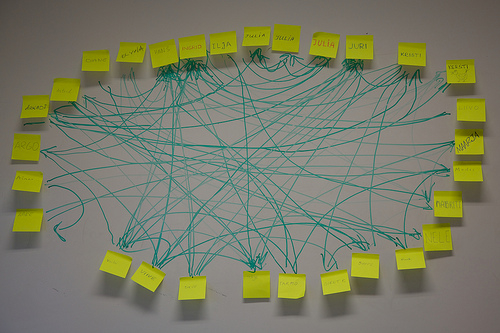

Developing connections with other people

I at first thought that perhaps one could say cMOOCs should allow participants to, at the very least, develop a set of connections with other people that are used for sharing advice, information, comments on each others’ work, for collaborating, and more. As discussed in my blog post on George Siemens’ writings on connectivism, what may be most important to a course that is run on connectivist principles is not the content that is provided, but the fostering of connections and skills for developing new ones and maintaining those one has, for the sake of being able to learn continually into the future.

And even though I understand what Downes and others say about participants in cMOOCs determining their own goals and deciding for themselves whether the course has been a success, cMOOCs have been and continue to be designed in certain ways for certain reasons, at least some of which most likely has to do with what participants may get out of the courses. Some of those who have been involved in designing cMOOCs have emphasized the importance of forming connections between people, ideas and information.

Stephen Downes talks about this in “Creating the Connectivist Course” when he says that he and George Siemens tried to make the “Connectivism and Connective Knowledge” course in 2008 “as much like a network as possible.” In this video on how to succeed in a MOOC, Dave Cormier emphasizes the value of connecting with others in the course through commenting on their blog posts, participating in discussion fora, and other ways. The connections made in this way are, Cormier says, “what the course is all about.” Now, of course, Cormier states at the beginning and end of the video that MOOCs are open to different ways of success and this is just “his” way, but the tone of the video suggests that it would be useful for others as well. Cormier says something similar in this video on knowledge in a MOOC: participants in a MOOC “are [ideally?] going to come out with a knowledge network, a network of people and ideas that’s going to carry long past the end of [the] course date.”

So it made sense to me at first to consider asking about the effectiveness or success of a cMOOC through looking at whether and how participants made connections with each other, and especially whether those continue beyond the end of the course. But again, there are some complications, besides the important questions of just how to define “connections” so as to decide what data to gather, and then the technical issues regarding how to get that data.

Would we want to say that the course succeeded more if more people made connections to others, rather than less? Or how about the question of how many people each participant should ideally connect with–I don’t think more is necessarily better, but where do we draw the line to say that x number of people made y number of connections with others, so the course has been a success?

This is getting pedantic, but I’m trying to express the point that when you really dig into this kind of question and try to design a research project, you would have to address this kind of question, and it’s kind of ridiculous. It’s ridiculous because there are so many different ways that connecting with other people could be valuable for a person, and for one person, having made one connection ends up being much more valuable than for another who has made 50. So much depends on the nature and context of those connections, and those are going to be highly individual and likely impossible to specify in any general way.

Further, what if some participants are happy to watch a few presentations and read blogs and lurk in twitter chats but don’t participate and therefore don’t “connect” in a deeper sense (than just reading and listening to others’ work and words). Should we say that if there are a lot of such persons in a cMOOC, the course has not been successful? I don’t think so, if we’re really sticking to the idea that participants can be engaged in the course to the degree and for the reasons they wish.

One possibility would be to ask participants to reflect on the connections they’ve made and whether/why/how they are valuable. One might be able to get some kind of useful qualitative data out of this, and maybe even find some patterns to what allows for valuable connections. In other words, rather than decide in advance what sorts of connections, and how many, are required for a successful cMOOC, one could just gather data about what connections were made and why/how people found them valuable. If done over lots of cMOOCs, one might be able to devise some sort of general idea of what makes for valuable connections in cMOOCs.

But would it be possible to say, on the basis of such data, whether a particular cMOOC has been successful? If many people made some connections they found valuable, would that be more successful than if only a few did? Again, this leads to the problems noted above–it runs up against the point that in cMOOCs participants are free to act and participate how they wish, and if they wish not to make connections, that doesn’t necessarily have to mean the course hasn’t been “successful” for them.

Looking at participation rates

One might consider looking at participation rates in a cMOOC, given that much of such a course involves discussions and sharing of resources amongst participants (rather than transferral of knowledge mainly from one or a few experts to participants). As this video by Dave Cormier demonstrates so well, cMOOCs are distributed on the web rather than taking place in one central “space” (though there may be a central hub where people go for easy access to such distributed information and discussions, such as a blog hub), and this means that a large part of the course is happening on people’s blogs, on Twitter, on lists of shared links, and elsewhere. So it would seem reasonable to consider the degree to which participants engage in discussions through these means. How many people are active in the sense of writing blog posts, commenting on others’ blog posts, participating in Twitter chats and posting things to the course Twitter hashtag, participating in discussion forums (if there are any; there were none in ETMOOC) or in social media spaces like Google+, etc?

This makes sense given the nature of cMOOCs, since if there were no participation in these ways then there would be little left of the course but a set of presentations by experts that could be downloaded and watched. Perhaps one could say that even if we can’t decide exactly how much participation (or connection, for that matter) is needed for “success,” an increase in participation (or connection) over time might indicate some degree of success.

But again, we run up against the emphasis on participants being encouraged to participate only when, where and how they wish, meaning that it’s hard to justify saying that a cMOOC with greater participation amongst a larger number of people was somehow more effective than one in which fewer people participated. Or that a cMOOC in which participation and connections increased over time was more successful than one in which these stayed the same or decreased (especially since the evidence I’ve seen so far suggests that a drop off in participation over time may be common).

Determining your own purposes for participating in a cMOOC and judging whether you’ve reached them

Another option could be to ask participants who agree to be part of the research project to state early on what their goals for participating in the cMOOC are, and then towards end, and even in the middle, perhaps, ask them to reflect on whether they’re meeting/have met them.

Sounds reasonable, but then there are those people–like me taking ETMOOC–who don’t have a clear set of goals for taking an open online course. I honestly didn’t know exactly what I was getting into, nor what I wanted to get out of it because I didn’t understand what would happen in it. And as noted above, even though there may be some predetermined topics and presentations, what you end up focusing on/writing about/commenting on in discussion forums or others’ blogs/Tweeting about develops over time, as the course progresses. So some people may recognize this and be open to whatever transpires, not having any clear goals in advance or even partway through.

For those who do set out some goals for themselves at the beginning, it could easily be the case that many don’t end up fulfilling those particular goals by the end, but going in a different direction than what they could have envisioned at the beginning. In fact, one might even argue that that would be ideal–that people end up going into very different directions than they could have imagined to begin with might mean that the course was transformative for them in some way.

Thus, again, it’s difficult to see just how to make an argument about the effectiveness of a cMOOC by asking participants to set their goals out in advance and reflect on whether or not they’ve met them. Perhaps we could leave this open to people not having any goals but being able to reflect later on what they’ve gotten out of the course, and open to those who end up not meeting their original goals but go off in other valuable directions.

This would mean gathering qualitative data from things such as surveys, interviews or focus groups. I think it would be good to ask people to reflect on this partway through the course, at the end of the course, and again a few months or even a year later. Sometimes what people “get out of” a course doesn’t really crystallize for them until long after it’s finished.

Conclusions so far

It seems to me that there is a tension between the desire to have a course built in large part on the participation of individuals involved, and the desire to let them choose their level and type of participation. In some senses, cMOOCs appear to promote greater participation and connections amongst those involved, while also backing away from this at the same time. I understand the latter, and I appreciate it myself–that was one of the things that made ETMOOC so valuable for me. I was encouraged to choose what to focus on, what to write about, which conversations to participate in, based on what I found most important for my purposes (and based on how much time I had!). There are potential downsides to this, though, in that participants may not move far beyond their current beliefs, values and interests if they just look at what they find important based on those. But overall, I see the point and the value. I expect there are some good arguments in the educational literature for this sort of strategy that I’m not aware of.

Still, this is in tension, to some degree, with the emphasis on connecting and participating in cMOOCs. Perhaps the idea is that it would be good for people to do some connecting and participating, but in their own ways and on their own time, and if they choose not to we shouldn’t say they are not doing the course “correctly.” It might nevertheless be possible/permissible to suggest that, given the other side of this “tension,” looking at participation or connection rates could be considered as part of looking at the success of a cMOOC? Honestly, I’m torn here.

[Update June 7, 2013] I just came across this post by George Siemens, in which he doubts the value of lurking, at least in a personal learning network (PLN). There are likely differences of opinion amongst cMOOC proponents and those who offer them, on the value of letting learners decide exactly how much to participate.

It is, of course, possible that the whole approach I’m taking is misguided, namely trying to determine how one measure whether a cMOOC has been successful or not. I’m open to that possibility, but haven’t given up yet–not until I explore other avenues.

I had one other section to this post, but as it is already quite long, I moved that section to a new post, in which I discuss a suggestion by Stephen Downes as to how to evaluate the “success” of MOOCs. In that and/or perhaps another post I will also discuss some of the published literature so far on cMOOCs, and what the research questions and methods were in those studies.

Please comment/question/criticize as you see fit. As you can tell, I’m in early stages here and am happy for any help I can get.