Professor Heemstra shared strategies for how researchers can deal with failure and how embracing failure can fuel success. It’s not uncommon for a typical researcher to accumulate thousands of failed results during a career. “Experiments fail every day. But as academics, we are never actually taught how to use this to our advantage.” Professor Heemstra saw this gap. Her lab co-founded a nationwide network called FLAMEnet—an education and psychology collaborative / research project—that investigates overcoming the fear of failure.

Being Afraid to Fail versus Being Comfortable with Failing

Challenges can be an opportunity for growth. Failure is inherent in what we do as researchers as not all experiments succeed and not every paper or grant submission gets accepted. How do we turn these “failures” into opportunities? How do we navigate self-doubt and “imposter syndrome”? And how can we become better as a result of these experiences?

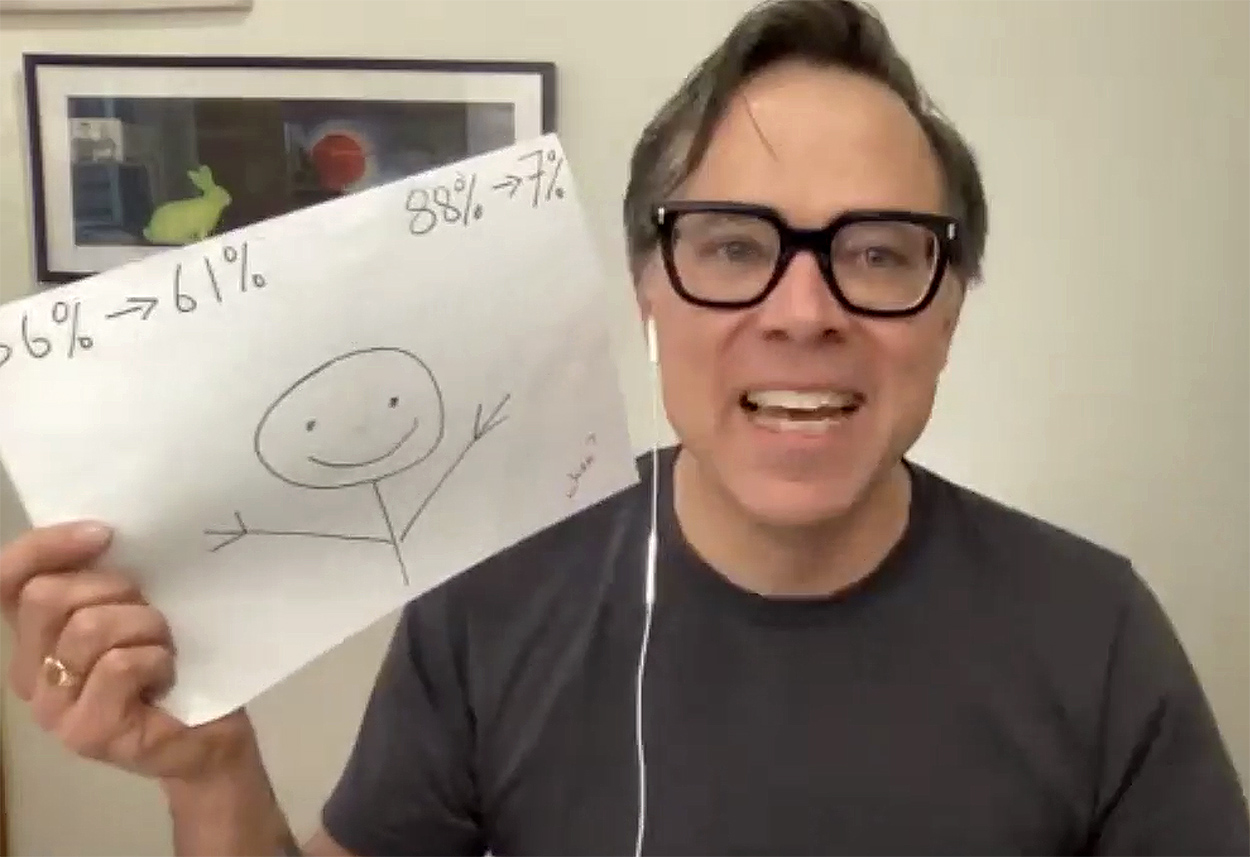

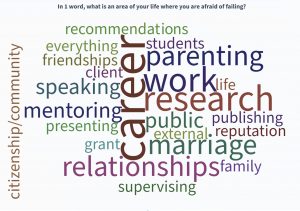

Results from the webinar audience poll answering the question: “What is an area of your life where you are afraid of failing?”

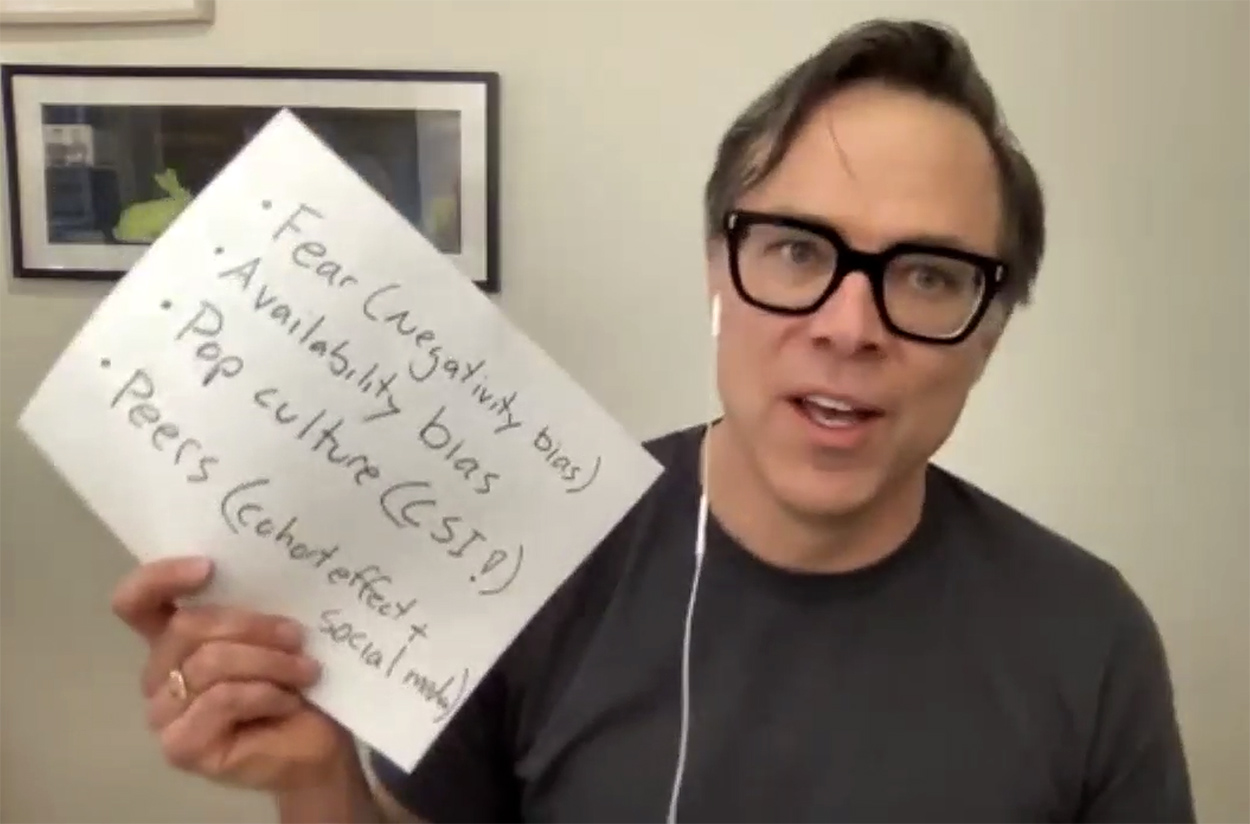

While researchers engage in research, their focus is typically on the actual research being done—and they often don’t consider other things that can impact the research process: how we think about our abilities; how we think about failure (and fear of failure); and what these things mean to us. All of these attitudes impact how we move through life and also how successful we are as researchers. Failure is painful and often unavoidable, but it can be a key step on the path to success. Leveraging failure toward success requires perseverance and resilience: the willingness to try again, to do things differently, and to do things more effectively. Moving from being totally terrified to a place of action starts by taking a step out of your comfort zone every single day.

Why should we help our students overcome their fear of failure? Why should we care? This raises questions:

- How and when do we expect students to acquire these skills? Most courses / curriculums do not teach perseverance and resilience, yet we expect researchers to have these skills.

- How can we help students in our courses cultivate these skills?

- How can we be lifelong learners in cultivating these skills ourselves?

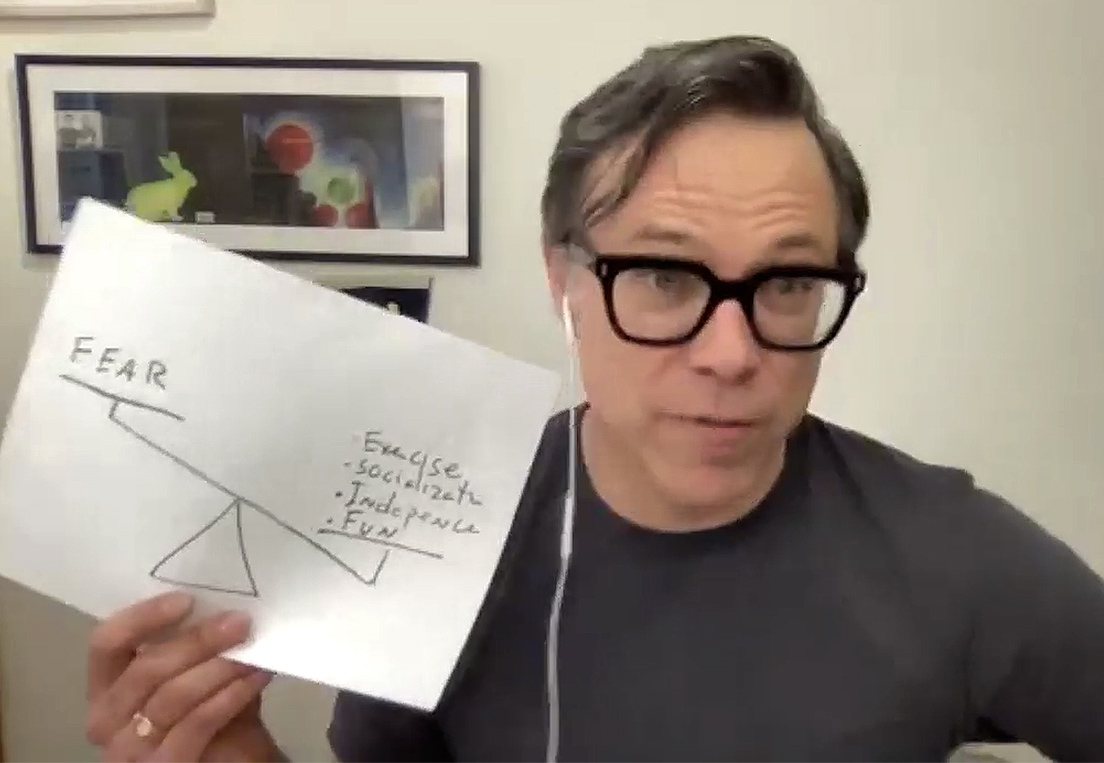

It can feel easier to push ahead despite possible failure when the things we are doing are for fun, in private or if the “stakes are low”. The stakes are much higher when we think about failing at work.

But if we avoid failing then we also:

- Avoid setting up important experiments

- Subtly sabotage experiments so we have an excuse when they don’t work

- Avoid seeking out help and advice

- Be more likely to discard the result go home instead of trying again.

There is a dichotomy: if we are open to the possibility of failure, it actually leads us to choices where we are less likely to fail. What can we do about this as researchers and educators? The answer is to change your mindset.

Fixed vs Growth Mindset

According to Carol Dweck, author of the book “Mindset”, a Fixed Mindset is static. It is defined as our belief that basic qualities such as intelligence and talent are traits that are set. That talent and intelligence alone create success. That you are born with a genetically set code for traits determining your skill level at certain things and are driven by the desire to appear intelligent. You are more likely to avoid situations where failure is possible, as a failure delivers unwelcome (and unfixable) feedback about your talent level. With a fixed mindset, you do not have a productive path forward after a failure occurs. Failure is considered to be a brick wall that cannot be overcome = a stopping point.

A Growth Mindset is active. It is the belief that we are all born with different levels of ability in a variety of areas. Intelligence and talent are just the starting point—you can develop your skills through hard work. Thus, hard work leads to success. With a growth mindset, you are driven by the desire to learn and improve. You are less afraid of new challenges, as a failure just indicates your current (not permanent) skill level. A failure is just a data point. Because you are capable of overcoming short-term failure, you can envision a path to success through hard work and improvement. Failure is considered as a simple bump in the road that can be overcome. It is just one point in the cycle towards ultimate success and can snowball into big outcomes.

What happens when your experiment fails? Fixed mindset:

- You might not have tried the experiment in the first place

- You subconsciously do something wrong in the setup – now you have an excuse when it fails

- When you get bad results, you blame other people or external factors “they ‘ruined’ your experiment”.

- You view trying again as fruitless

- But, give it a half-hearted effort to keep advisor/professor happy

Growth mindset:

- You acknowledge that experiments might not work

- You give your best effort to get things right

- When you get a bad result, you view the experiment as a challenge that you want to solve

- You view trying again as productive and fun because you believe hard work can (eventually) yield progress

- It doesn’t matter what others think because you know you’re giving your best

FLAMEnet

Realizing the importance of these concepts, Professor Heemstra began delivering a 4-part active “Failure Training” curriculum that combines videos, lecture, social media and reflective writing into her lab courses. She then recognized this training could be improved if her lab became involved in education research. Heemstra reached out to an interdisciplinary team of psychologists, education researchers and STEM instructors across multiple institution types. Soon after, the “Failure as part of Learning, A Mindset Education Network”, or FLAMEnet was born. Over 3 years, membership to FLAMEnet has expanded to include more than 100 members. The focus has now expanded to include multiple intrapersonal factors and their impact on student success, analyzing how students learn and their retention in STEM.

The Power of Yet

Success may be defined by the moments when everything is going right, but it is largely determined by what we do in the moments when everything is going wrong. It is important to shift our thinking and embrace the adage: We are not there…yet. A more realistic plan is to adopt a growth mindset pathway. Tenured faculty likely achieved major successes by stepping out of their comfort zone a little bit every day, doing things that were a bit challenging—one step at a time. It is perfectly fine to figure things out as you go. Dealing with the failure of not achieving goals when we expect to achieve them can be the most important days of our careers. These days make us stronger and likely more empathetic. They help us gain clarity and broaden our vision of what is possible. As scientists, our days are filled with running experiments because we see there is something interesting to learn. In reality, our whole life is an experiment and it’s the most interesting experiment you will ever run.