IMHA recently held a webinar targeting science misinformation with Professor Timothy Caulfield, Professor of Law at the University of Alberta and Research Director of the Health Law Institute. Drawing from examples in his new book “Relax, Dammit!”, Professor Caulfield took us through thought-provoking topics ranging from the infodemic to negativity bias and from cultural forces to personal branding. Here are 7 highlights.

The infodemic and misinformation

- We are in the middle of an infodemic and it is impacting both our physical and mental health. This, in turn, affects our ability to filter out good from bad information.

- Statistics Canada reported that 96% of Canadians see misinformation daily and 90% of Canadians receive their information online.

- Surveys also found that 61% look at their phones immediately after waking up in the morning (75% while on the toilet!) and approximately 80 times throughout the day while on holiday.

- While not entirely a social media phenomenon, the spread of misinformation is largely attributed to social media.

Observational studies and negativity bias

- Observational studies are over-represented in the popular press. This is what the general public typically sees.

- Only 19% of observational studies represented in popular press disclose that they are observational and note the limits of those studies.

- People, in general, have tendency to latch on to negative news and allow that news to impact behaviors and beliefs.

- Negativity bias is powerful. The popular press capitalizes on this because negative headlines outperform positive ones.

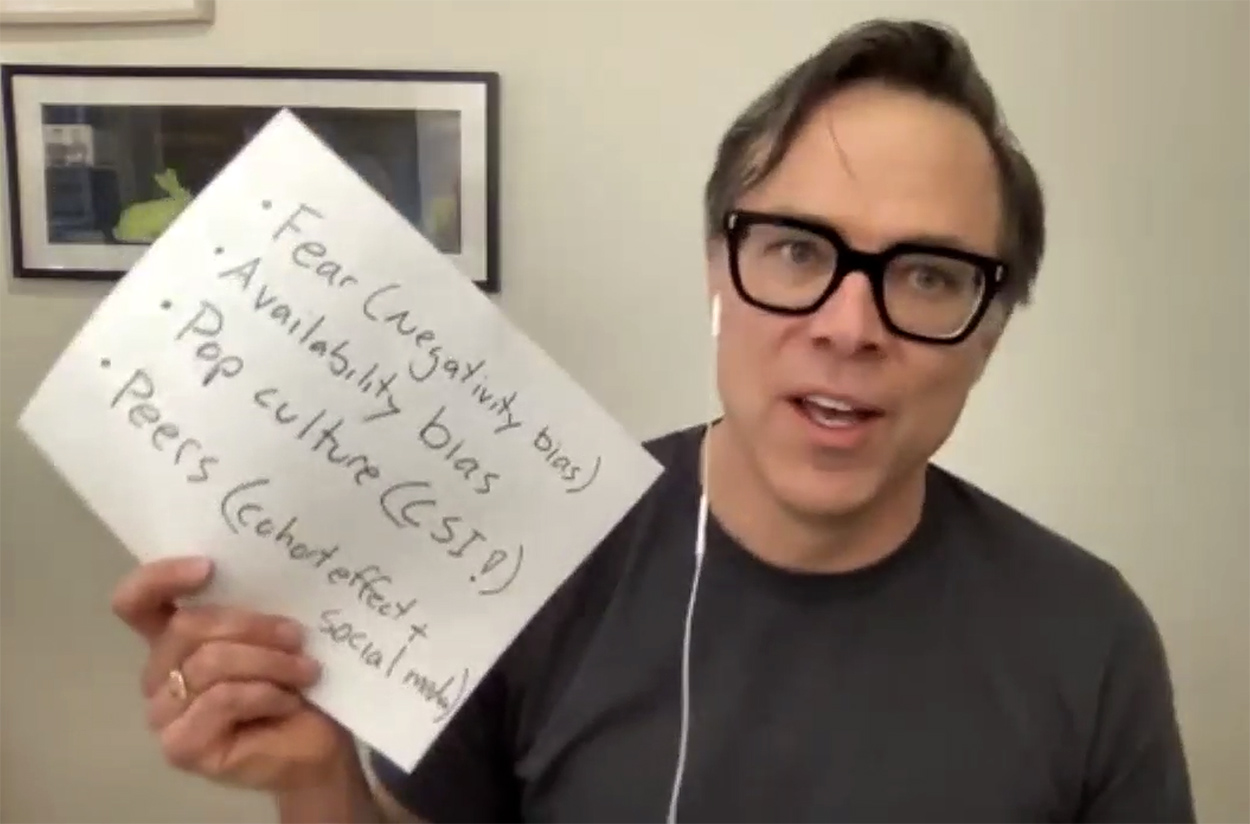

Cultural forces, availability bias and pop culture

- Social trends can impact our decisions which in turn can lead to dominant cultural norms. For example, driving kids to school has become a societal norm for fear of “stranger danger”—the fear of children being abducted on their way to school.

- A policy statement from the University of British Columbia determined that the chance of a child being abducted by a total stranger is one in 14 million.

- Just one adverse event that happens anywhere in the world (not necessarily in Canada) can easily overwhelms all statistics, impacting decisions and actions. Powerful anecdotes can overwhelm our scientific thinking.

- Pop culture—especially TV programming and movies—can deeply impact our perception of crime rates and fear. This in turn can also influence the decisions we make.

Myths and personal identity

- When presented with an enduring belief, a good rule of thumb is to ask yourself “Is this true?”. For example, drinking 8 glasses of water per day for health. There’s no evidence for that.

- The marketing industry strongly influences why some myths endure for decades and become cultural norms.

- Tap water in most parts of Canada, is safe to drink. Yet, the wellness industry has turned water (and related peripheral products) into a multi-trillion dollar industry.

- When something becomes part of your personal brand (‘I’m a Starbucks drinker’), it becomes much more difficult to change your mind and marketing experts know this.

- We are seeing this happen right now with misinformation around the pandemic, masks and vaccines.

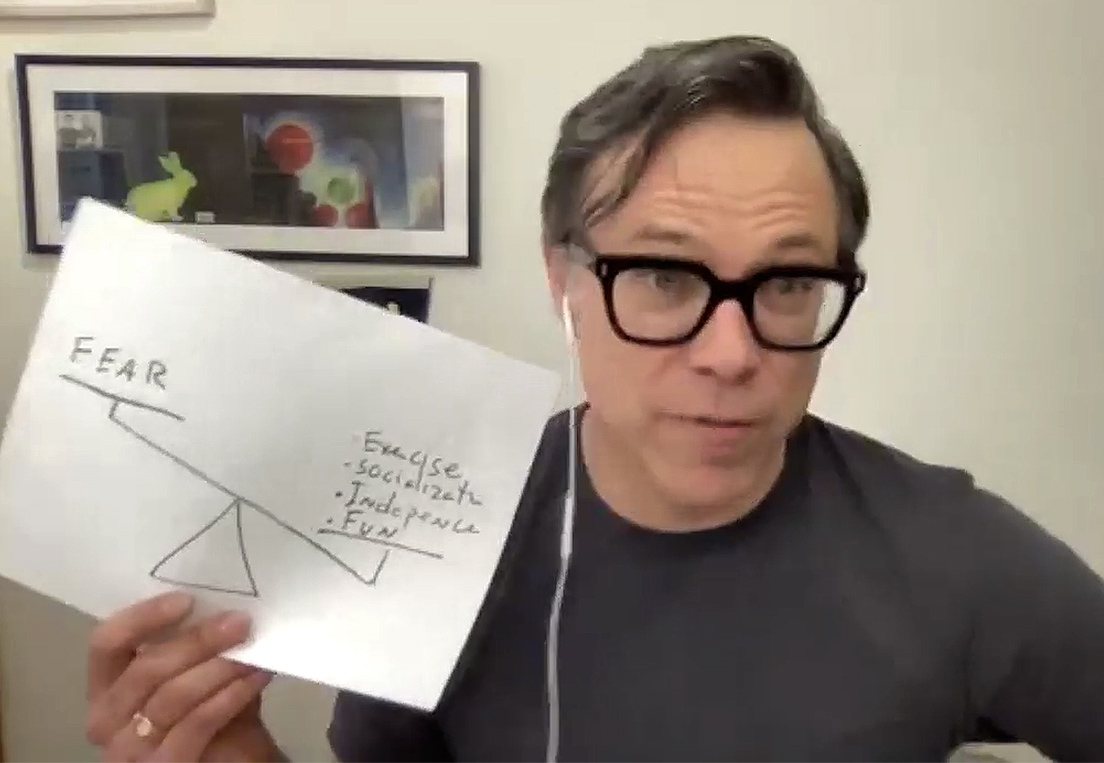

Exercise

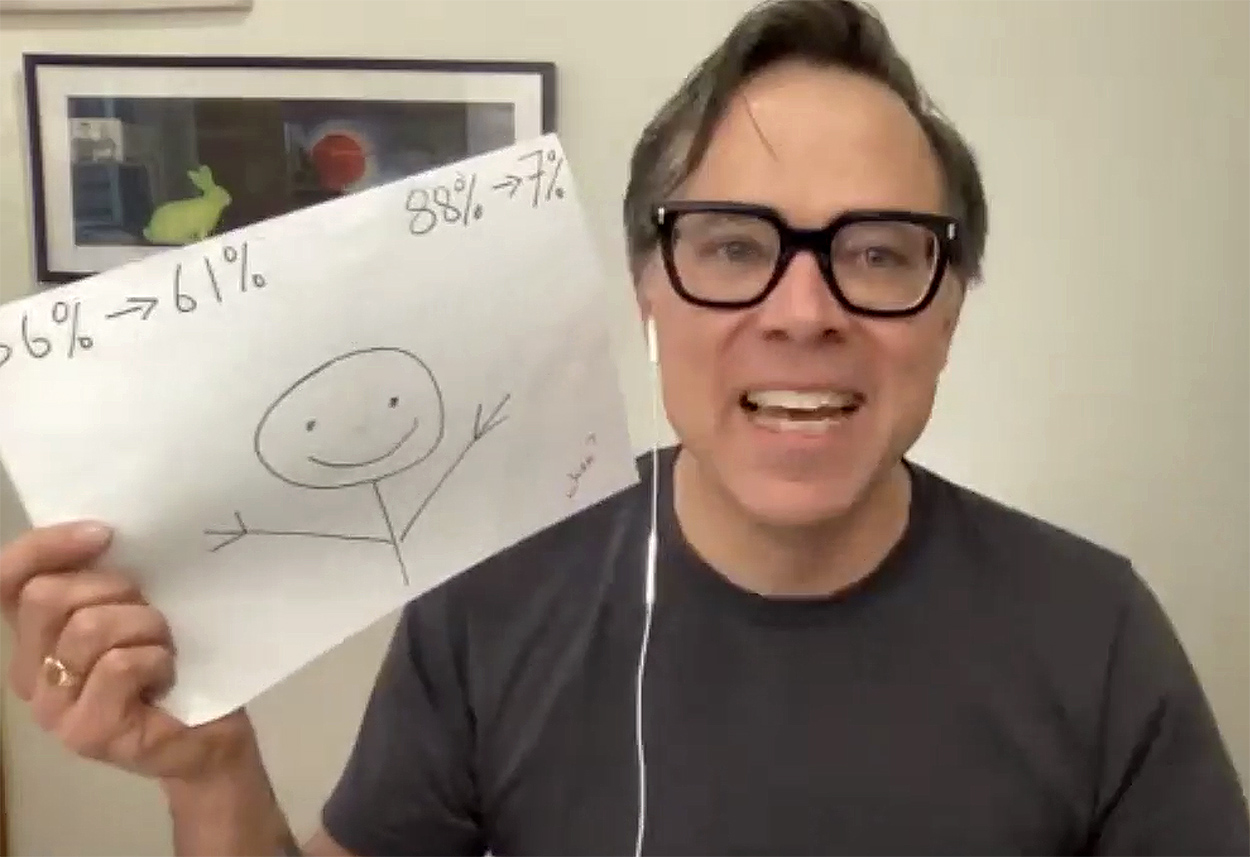

- In a study of people who exercise, 36% overestimate the amount of exercise they do. In those who don’t exercise enough, 61% overestimate the amount they do. For parents, 88% feel their children get enough exercise when approximately 7% of children meet guideline activity levels.

- Exercise guidelines, technology and monitoring can be complicated or confusing. Often, when you try to quantify something, people enjoy it less and they stop the activity.

- How much to exercise? The answer is simple: just move.

Illusion of Difference

- The Illusion of Difference—and this is something that impacts all of us all the time—is the idea that you think you can tell the difference between things when you can’t.

- In a study from Edinburgh, Scotland, nearly 600 people were asked if they could tell the difference between cheap and expensive wine. Just 53% got the answer correct (basically, chance).

- Be aware that technology is always criticized, whether it’s comic books, movies, television, computers, or the internet—and has been since the Gutenberg printing press in 1440. We need to be cautious about technophobic approaches and be sure decisions are based on good data.

How to Debunk Misinformation

- Just being aware of these cognitive biases matters. It allows us to make more informed choices.

- Debunking does work. It is up to us to do it.

- The backfire effect—the belief that people become more entrenched in their views when presented with facts—isquite rare.

- Rule #1: Listen! People’s concerns are based on different things.

- Using good science matters! Referring to the body of evidence is likely to be more persuasive.

- Highlight the gaps in logic used to push the misinformation: anecdotes, things that play into negativity bias, testimonials, misrepresentations of risk, conspiracy theories, etc.

- Be humble. Be nice. And be authentic when defining misinformation.

- Creativity wins. We have to start using narratives, stories, art, and humor, in order to get across the good stuff.

- Good science should be shareable.

- Always remember that the general public is your audience, not hardcore deniers.

- Relax! Current research shows how important it is just to have people pause … and reflect. By nudging Canadians to pause first—and share after—we can have a measurable impact on people sharing misinformation.

- Join Science Up First (#ScienceUpFirst) / @scienceupfirst). It is an initiative for us to share good credible information on social media. Go Science!