In his book Making, Tim Ingold proposes a full re-evaluation of how we approach media, product, process and how we interact with them. Much of his theory clearly reflects Marshall McLuhan’s understanding of media, namely that the “media is the message”, not a product that is separate from its intended purpose (McLuhan 2).

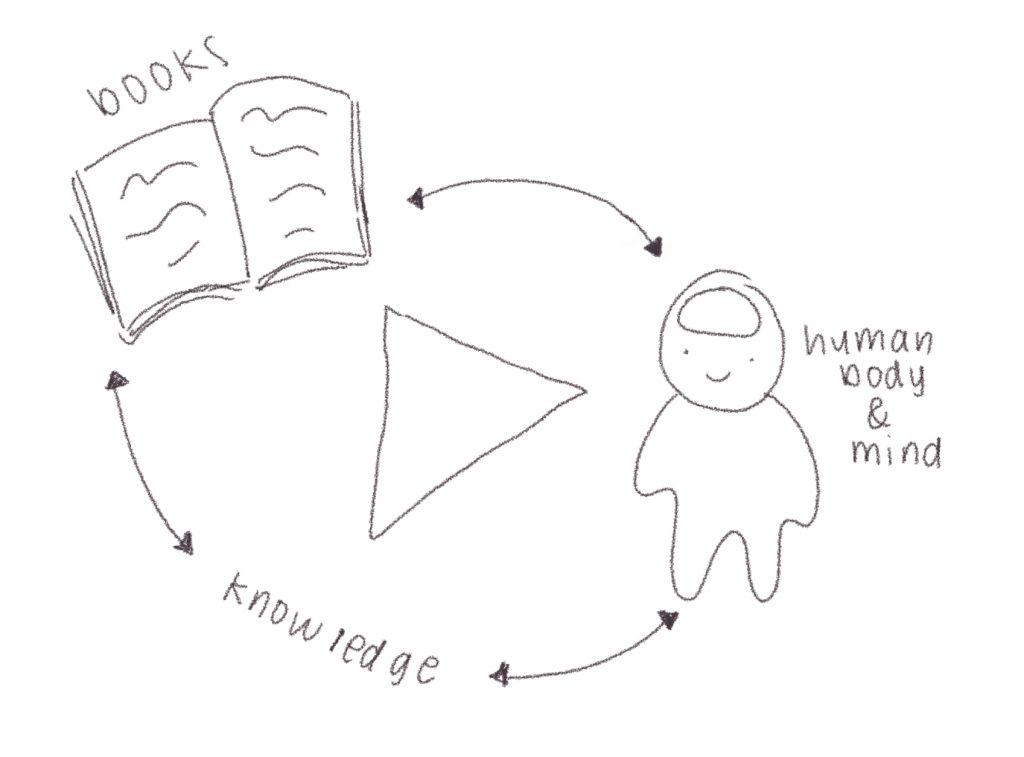

Ingold’s propositions reflect an arguably more realistic way of examining the world. The world and what it contains (including us as audiences) are irrevocably intertwined, simultaneously affecting and being affected by one another. Not only is the world an ever-fluctuating, ineffable entity where nothing is ever concrete, every perception of the world is unique. Ingold proposes that the relationships between media and audience, including those that we form within MDIA300, can be divided through three main lenses: learning, making, and telling.

Learning

Ingold first mentions restructuring our approach to media in the book’s introduction, prompting the reader to examine how they learn. He cites Gregory Bateson’s concept of deuterolearning, a method that aims to provide us with “facts about the world as to enable us to be taught by it”(Ingold 2). This concept lays the foundation for a more communicative viewpoint of learning, using the world as an active asset used to enrich our knowledge rather than an object whose information remains stagnant and separate from its contexts.

Ingold relies heavily on the distinction between anthropology and ethnography to effectively convey how his definition of learning differs from its academic understanding. Similar to anthropology, Ingold claims we must “learn from” the subject of our interests instead of solely documenting our findings, which is otherwise known as ethnography (2-3). Despite these distinctions, anthropology and ethnography customarily work in tandem, providing different elements that together create a more beneficial learning experience. The documentarian process of ethnography provides the information needed to effectively conduct an anthropological study.

Ingold’s concepts of learning are directly applicable to MDIA300 overall. We are instructed to further our understanding of our readings by considering what the information they contain can tell us about how they are situated in the world. This class facilitates inter-exchange between media and audience by forcing us to reflect on these ‘finished’ media products and how they relate to one another and the world as we understand it. Moreover, we are encouraged to discuss our understanding of this media, expanding our perspectives and learning from one another. The collaborative nature of this class allows us to partake in what Ingold defines as an effective learning process.

Our work on the class blog mirrors Ingold’s discussion of anthropology and ethnography. The assignments that are published to the blog act as an ethnographic documentation of our learning, while our discussion and comments fulfill the anthropological acts of learning with one another, instead of taking what we say at face value.

Making

Building off his discussion of learning, Ingold transitions to defining the titular concept of the book: making. Ingold constantly redefines making, weaving complex layers through his definition of the word. Initially, he defines making as “a process of growth”(Ingold 21). Expanding on this, Ingold invokes hylomorphism, explaining the concept while comparing a maker’s intentions. A maker working with a hylomorphic worldview–looking to inflect their image onto material–has more egocentric intentions than one who is observing making as a process of growth, focusing on the process rather than the ‘product’ (Ingold 21).

To further reinforce his definitions, Ingold relies on artistic examples to effectively analyze the process and products of making. Ingold’s example of the Ancheluen handaxe prompts the reader to reexamine how they understand the ‘final’ products they encounter. He warns us against “conflating the final form of an artefact, as it is recovered from an archaeological site, with the ‘final form’ as it might have been envisaged by its erstwhile maker”(Ingold 39). In class, we study media in a way that highlights its different interpretations. Therefore, no media can have a ‘final form’ as we are constantly reexamining it and what it means. Similarly, Ingold uses a pottery wheel to more accurately describe how we should view our relationship with making media. He views making not as “an imposition of form on matter but a contraposition of equal and opposed forces immanent respectively”(101). In essence, we must work in tandem with media, respecting its place in the making process, and acknowledging different affordances.

The assignments we make for class adhere to these definitions. For example, the Critical Terms chapters we covered at the beginning of the term continue to be relevant as we move onto new subjects, rendering the assignments we created in response to them dynamic documentations of our learning. The analyses are a comprehensive foundation for the more complex applications this material has been used for in the many posts that are now on the blog. Our making is a byproduct of our learning, and because our learning is a dynamic and conversational process, the analogies, comparisons, and connections that we make are dynamic and conversational as well.

Telling

Ingold further develops his theories of dynamically approaching media through his discussion of telling. He separates the term ‘telling’ into its two definitions: being “able to recount the stories of the world” and being “able to recognise subtle cues in one’s environment and to respond to them with judgement and precision”(Ingold 110). He emphasizes that the act of telling is not only “a vector of projection” meant to impute an image into reality but an active member of the relationship between image, maker, and material world. In effect, telling is a “process of thinking” versus a “projection of thought”(Ingold 128). In this way it is the act of co-operating with one’s work, invoking Ingold’s philosophies of making and learning in the process.

These definitions of telling integrate themselves with Ingold’s definitions of making and learning and are implemented in our course’s workload, including our study of Sherry Turkle’s Evocative Objects. Without Ingold’s methods of learning, we could not fully understand the scope of the material we observe. We would not be capable of forming a relationship between ourselves and Evocative Objects, failing to fully contextualize each objects’ message both in its creation and in our understanding. In essence, we would not be able to tell what meaning lies in the media. Without Ingold’s multi-faceted approach to making media, we would not reach the full capacity of our ability to tell others our message, including applying Turkle’s theories to objects in our own lives. We worked with the text to fully understand it. In that understanding, we told each other our findings, exhibiting the interconnectivity between Ingold’s concepts of learning, making, and telling.

Conclusion

Ingold’s theories concerning learning, making, and telling are applicable to how we have observed media throughout our study in MDIA300 thus far. We use the media we study as an active participant in our learning, making connections that continue to develop even after the publication of our assignments, and using the skills and understanding we gain through these methods to effectively tell our stories and points to our peers.

Critical Terms for Media Studies, edited by W.J.T Mitchell and Mark, B.N. Hansen, The University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Ingold, Tim. Making, Routledge, 2013.

McLuhan, Marshall. “The Medium is the Message,” Understanding of Media: The Extensinos of Man, New York, NY, 1964.

Turkle, Sherry. Evocative Objects: things we think with, MIT Press, 2007.

Image by Molly Kingsley

Written by Molly Kingsley