Indigenous Nurses Day 2023: Health, Healing & History

This year, undergraduate BSN students at UBC-V Nursing, supported by funding from the Consortium for Nursing History Inquiry and the Transformative Health and Justice Cluster, initiated a project to celebrate Indigenous Nurses Day on April 10, 2023. BSN student Samantha Bishop initiated the project, which involved eight BSN students and one faculty advisor. Students reviewed a total of six books that were written by Canadian Indigenous authors and addressed Indigenous conceptions of healing and wellness. The books were purchased from Indigenous-owned bookstores (Massy Books and Iron Dog Books) in Vancouver. At the conclusion of this project, copies of the books were donated to a local hospital so that health care workers will be able to access the books. In each review, the students also discuss how the book may be relevant to health care practitioners and current nursing practice. What follows is a list of the participants and the reviews of each book.

History of Indigenous Nurses’ Activism in Canada

Dr. Lydia Wytenbroek

April 10, 2023, marks the second annual celebration of Indigenous Nurses Day in B.C. It allows us to take a moment and consider the achievements of First Nations, Inuit and Métis nurses and their efforts to improve the health and wellbeing of Canadians.

Indigenous Nurses Day in BC marks the date of birth of Charlotte Edith Anderson Monture, born April 10, 1890, who is recognized as the first Indigenous Registered Nurse in Canada. Monture grew up on Six Nations Reserve near Brantford, Ontario. Although she applied to nursing schools in Ontario, she was denied admission (Wytenbroek & Grypma, 2023). Historian of nursing Kathryn McPherson (2005) notes that there were no Black or Indigenous applicants admitted to Canadian nursing schools before the 1940s (p. 83). However, Monture gained admittance to New Rochelle Hospital School of Nursing in New York, graduating first in her class in 1914. After working as a public health nurse in New York and serving with the American Medical Corps overseas during the First World War, Monture returned to Six Nations Reserve in Canada in 1919. She worked as a nurse and midwife at Lady Willingdon Hospital on the reserve until her retirement in 1955 (McPherson, 2005, p. 86). Monture also became the first Indigenous woman to gain the right to vote in a federal election. For the rest of her life, Monture advocated for better health care and an extension of voting rights for Indigenous peoples in Canada.

While Monture is recognized as the first Indigenous registered nurse in Canada, Indigenous healers and midwives have played essential roles in their own and white settler communities for centuries, as documented by historian Kristen Burnett and others (Burnett, 2010). Yet these healers, nurses and midwives are often excluded from nursing histories because they fall outside the boundaries of the concept of the professionally educated nurse (Wytenbroek & Vandenberg, 2017).

Indigenous nurses have a long history of working for better health care for Indigenous people in Canada. In the 1970s, Indigenous nurses came together to form a professional association (RNCIA), now called the Canadian Indigenous Nurses Association (CINA). They were aware of the failures of the colonial health system (see Maureen Lux’s Separate Beds for more context on segregated healthcare in Canada) and advocated for Indigenous control over Indigenous health services. Its founding members included Jean Goodwill, Jocelyn Bruyere and Ann Callahan. Historian Mary Jane Logan McCallum (2013) notes that the primary aim of the organization was to improve the health of Indigenous communities and expand the participation of Indigenous nurses in the provision of Indigenous health services. McCallum argues that these goals were revolutionary because the association sought to “transform the very nature of the relationships between Indigenous people and governments, and to reject the colonization of Indigenous health” (McCallum, 2017). Indigenous nurses remain underrepresented in the nursing workforce, and CINA continues to work to address inequities in nursing and health care.

The book reviews that follow shed light on the importance of Indigenous perspectives on health and wellness. Each student has identified important ways that these books can assist nurses in thinking about how to incorporate these teachings into their current practices. The Consortium for Nursing History Inquiry is pleased to support this amazing student-led initiative!

Book Review #1

Book: Held by the Land: A Guide to Indigenous Plants for Wellness (2023)

Author: Leigh Joseph

Book Review Author: Alina Benischek

Leigh Joseph, the author of this book, describes herself as an Indigenous ethnobotanist, woman, mother, and entrepreneur from the Skwxw′u7mesh nation, in what is colonially known as Squamish, British Columbia. She has dedicated her personal and professional life to establishing and maintaining meaningful connections with the land and sea to grow and share her knowledge as a researcher, harvester, and community organizer. Joseph has empowered many people to move toward better health and healing by sharing her ancestral knowledge about Indigenous spirituality, nutrition, self-care, and community relationships.

In Held By the Land, Joseph explores the traditional foods and ecological knowledge of the Skwxw′u7mesh people, bridging her Indigenous cultural perspective and scientific background as a botanist. The book draws on Joseph’s personal experience and knowledge to showcase the complex relationship between land, people, Indigenous history, and traditional food practices. Joseph also relates her knowledge of Indigenous foods and plants to contemporary issues of food sovereignty, sustainability, and climate change.

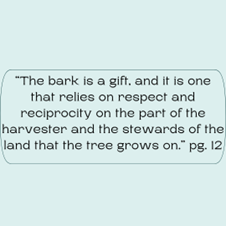

Joseph explains the intimate relationships between environmental sustainability and Indigenous cultural food practices, highlighting the value of reciprocity and protection while harvesting plants. For example, each stage of the plant’s life cycle, the best season for growing the plant, and the scarcity of the plant are explained to the reader so that the reader can come away with an awareness of more ethical approaches to food harvesting. In addition to this ethnobotanist lens, Joseph provides a multitude of different plant and non-plant-based recipes for food and natural beauty products that use only local ingredients from the Squamish area of British Columbia. She explains the various healing properties of each of the plants and provides guidance and recipes on how to best utilize them. Joseph calls on her learners to harvest, cook and utilize the plants with good intentions and heart, as she explains that feelings influence what we are creating. While exploring and learning more about these plants and recipes, I learned to be more mindful and grateful for these revitalizing plants as I grew in my knowledge of these unique cultural resources and their sacred, place-based harvesting.

Additionally, in Held By the Land, Joseph explains how the land and plants can be utilized to bring about wellness for the individual, the environment, and the community. Each of these plants has nutritional and medicinal properties that can provide healing and unity in the community. Since plant harvesting is based on traditional teaching and knowledge, these practices can be used to improve food sustainability, food security, and resiliency in families and communities. However, in many Indigenous territories, these sustainable cultural practices and traditions have been lost or forgotten because of colonialism, community segregation, and intergenerational trauma. Joseph explains how she has found refuge and inner peace through plants, and she has written this book to share and spread these traditional teachings with others in order to build stronger communities.

As a nursing student and white settler on the traditional and unceded territory of the Coast Salish people of Vancouver, British Columbia, this book has broadened my perspectives on Indigenous cultural healing and health practices and enabled me to consider how I can incorporate this knowledge into my daily life and professional practices in nursing. I highly recommend trying out Leigh’s food and beauty recipes. As a seafood enthusiast, I especially enjoyed the Lh′asem Seafood Soup. The recipe has a good balance between vegetables and protein and can be easily adopted to your personal preference. I decided to make the soup with halibut and shrimp, good quality olive oil, coconut milk, seafood stock, organic tomato sauce, and a medley of diced vegetables (bulblets of traditional lh’asem plants from the organic specialty food market along with celery, onion and carrots). These staple ingediates along with paprika, salt and a pinch of cayenne pepper made the dish so flavourful, nutritious, comforting and fulfilling! I was even able to access some of the ecologically sustainable ingredients from a local fish market, The 7 Seas, and a local food market for the halibut, which was a positive experience. Now that we are entering Spring, I am excited to try out the Yetw′ana′y (salmonberry) Chia Spread, described for its tangy-sweet flavour, and the N′asta′ma′y (saskatoon berry) Granola Bread for its nutty, wholesome ingredients. I would highly recommend this book to anyone wanting to build their Indigenous cultural knowledge regarding plant ecology, healthy eating, holistic health, and community wellness.

Book Review #2

Book: Northern Wildflower (2018)

Author: Catherine Lafferty

Book Review Author: Hannah Buhr

Catherine Lafferty published Northern Wildflower in 2018. Lafferty is a Dene woman who served as a Council Member for the Yellowknife Dene First Nation, where she held the portfolio for justice, heritage, and housing. Lafferty has a Bachelor of Arts in Justice and is a law student at the University of Victoria. She says that Northern Wildflower was written in hopes of “inspiring, encouraging and giving hope to the Indigenous Peoples of Canada that are in the struggle. Together we can break the cycle of intergenerational trauma and echo our voices loud and clear, in unity and solidarity, so that every person will understand the detrimental effects that colonialism has had on our livelihood throughout Canada’s history” (p. 1).

Northern Wildfire is a memoir, in which Lafferty ties her lived experience to the discrimination she has faced as an Indigenous person in Canada.. For example, Lafferty describes growing up in an unloving foster home without the presence of her mom or grandma. Her experiences are linked to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) Calls to Action which support keeping Indigenous families together and providing Indigenous children with culturally-appropriate environments. On another occasion, Lafferty recounts a violating experience in the courtroom following abuse. The TRC Calls to Action note that lawyers should receive cultural competency training, so that Indigenous people are treated with respect and dignity when seeking justice. Lafferty faced the possibility of having her child taken away from her when she wanted to treat him with traditional medicines. Again, the TRC Calls to Action call for the Canadian healthcare system to recognize the value of Indigenous healing practices. Thus each of the TRC Calls to Action respond to the many oppressions that Indigenous peoples face within Canada. Northern Wildflower emphasizes just how tangible and widespread Indigenous peoples experiences of oppression are and the need for justice.

Despite this, Lafferty’s life has been greatly shaped by her culture and her family. The lessons given to her by her grandmother combat the oppression that has manifested in her life. When she felt as though she didn’t belong within the foster care system, her family told her she belonged. When the Canadian state separated Indigenous people from the land, her grandmother taught her to respect the land. In turn, Lafferty teaches these principles to her children. By passing Indigenous teachings on to the next generation, she is also teaching them to stand up against oppression.

Northern Wildflower is a great reminder that nurses are often present, often unintentionally, in some of our patients’ most meaningful life moments, without necessarily always understanding their whole story or the context of their lived experiences. Several of these moments are even described in Northern Wildflower, as Lafferty and her family receive medical treatment that shapes their lives in pivotal ways.

Upon learning so much about Lafferty’s life, I was reminded that though I often come to patient encounters with knowledge of pathophysiology, there is so much that I do not know about the person I am interacting with. I don’t know if the client has faced systemic oppression, or what they might be struggling with, or how they view the healthcare system. But as a nurse, I can make time to learn from my client and ask them how I can best support their needs. Northern Wildflower was an inspiring memoir that can remind all of us about the deep understanding that needs to be built so that every person can be “brave, strong, wild, and free” (p. 147).

Book Review #3

Book: Decolonizing Trauma Work: Indigenous Stories and Strategies (2014)

Author: Renee Linklater

Book Review Author: Reilly Ische

Dr. Renee Linklater’s book, Decolonizing Trauma Work: Indigenous Stories and Strategies (2014), explores healing and trauma work among Indigenous communities on Turtle Island. Linklater’s Anishinaabe name is Ozhaawashkobinesi (Blue Thunderbird), and she is from the Otter Clan of the Rainy River First Nations in the traditional territory of Treaty #3. She is the Senior Director of Shkaabe Makwa at CAMH in Toronto, the first hospital-based center in Canada for culturally driven health justice and wellness.

Linklater’s mother was from the Manitou Rapids-Rainy River First Nations in Northwestern Ontario and her father was of English and Scottish settler heritage. However, Linklater was removed from her family during the Sixties Scoop, and was adopted by a second-generation Ukrainian immigrant family. She did not return to her Anishinaabe community until she was nineteen. Early in the book, she writes, “We (healthcare providers) have to come to terms with who we are and how we come to do the work we do” (p.11). Her personal story is an incredible guide that allows the reader to reflect on their own worldview and how it impacts their relationship with healthcare.

The book is a collection of research on how Indigenous health, colonialism, and Western psychiatry interact. It also discusses how Indigenous healthcare practitioners are leading new conversations on wellness and a more holistic view of trauma. . Trauma is defined in this book as the reaction or response to injury, rather than being labeled a disorder. This distinction is critically important to understanding Indigenous trauma theory. It is also a recurring theme that comes up in dialogues that Linklater has with ten Indigenous healthcare practitioners, who each provide their own perspectives on their approaches to decolonizing trauma work.

Unlike Western psychiatry, which focuses on the individual and illness in isolation, traditional Indigenous wellness highlights the interconnectedness of mind, body and spirit, while also accounting for how a person cares for themselves and their community. The historical outlawing of ceremony removed Indigenous peoples’ way of addressing trauma responses. Thus, it is important for wiidokaazowin (helpers) to educate themselves on the ways of miyupimaatisiium (being alive well) for healing to occur. To do this, Linklater writes that “resources that address what was taken away need to be made available… [to] advocate for the delivery of workshops that teach culture, language, parenting skills, anger management and problem solving skills” (p. 93). While the book educates readers on the systemic barriers that restrict clients from accessing Indigenous healers, it also provides multiple frameworks for integrating decolonial approaches into the Western mental health practices.

As a nursing student, I am taking to heart the words of Tina Vincent, an Algonquin woman from Barrier Lake First Nation in Rapid Lake, Quebec who is interviewed in the book. She has 24 years of experience as a counselor, and is the program coordinator for Oshki Kizis Lodge, a women’s shelter in Ottawa. She says, “How can you work with someone if you don’t know their history… I think the intentions are good, but when you come armed only with a diploma, you’re not going to last long” (p.55). As nurses, we are positioned to build relationships with our clients, learn their stories, listen to their needs and advocate for treatments that they deem are in their best interests, including connecting with them to cultural and ceremonial resources. To do this effectively, we need to ensure that we treat people in a way that recognizes the whole person as opposed to just a patient with a particular disease diagnosis, make efforts to connect with family and community, and be open to a different reality. For those that haven’t yet ventured into learning Indigenous wellness practices, this book is a great resource. In conclusion, I leave you with the words of interviewee Ed Connor,from the Wolf Clan of the Kahnawake Mohawk Territory and an Elder advisor on the Board of Directors for the Native Mental Health Association of Canada. He states: “Indigenous healing methods have been successfully utilized for longer than Euro-Western approaches to psychiatric healing and mental health” (p. 124).

Book Review #4

Book: Facing the Mountain: Indigenous Healing in the Shadow of Colonialism (2021)

Author: Dr. Catherine Kinewesquao Richardson

Book Review Author: Michele LeBlanc

In Facing the Mountain: Indigenous Healing in the Shadow of Colonialism, Dr. Catherine Kinewesquao Richardson shares a compelling narrative that integrates personal experience with an analysis of neo-colonial structures that perpetuate systemic racism and colonial violence. Richardson, an accomplished author, storyteller, academic, and activist, is a member of the Métis nation, with Red River, Cree and Gwich’in ancestry. Richardson is the Director of First Peoples Studies at Concordia University in Montréal, Québec. She is a professor in the School of Community and Public Affairs and is the Co-Founder of the Centre for Response-Based Practice and Co-Director of the Centre for Oral History and Storytelling. She brings all of this knowledge and experience into this work.

In Facing the Mountain, Richardson aims to demonstrate the reality of health and social inequities for Indigenous peoples due to the ongoing impacts of colonization in Canada. For example, Richardson identifies victim-blaming as a colonial tool for propagating indignities against Indigenous people. Rather than identifying the perpetrators and colonial structures that impact Indigenous peoples’ health, victim blaming places the responsibility of inequitable health outcomes solely on Indigenous people. Dr. Richardson identifies widespread victim-blaming as a means of colonial avoidance of responsibility. Furthermore, she relates the colonial tool of categorizing Indigenous populations as “vulnerable” rather than “vulnerabilized” to her own health. Although healthcare providers might consider her Indigenous status as a vulnerability, she identifies toxin exposure, low income, unsafe water, and expensive food as primary risk factors – and tools of colonialism – that influence her position of vulnerability. This is an important insight for nurses who may be quick to label Indigenous peoples as vulnerable.

Richardson notes that she has had four hip replacements and two cancer diagnoses, all of which she links to the 1950s when her grandfather moved to Uranium City, a mining town in northern Saskatchewan. Colonial industries, especially mining, rely on government forces to infiltrate Indigenous communities and violate land and human rights. The Canadian government has historically (and continues to) deliberately withhold information from Indigenous people related to the health impacts of uranium mining as they initiate these cultural and land-based attacks in Indigenous communities. Richardon’s family members kept ore in the basement, used radioactive pitch blades to dig flower beds, and worked in uranium laboratories. Entire Indigenous communities ate fish from radioactive rivers and breathed radioactive dust. The health impacts of radioactive colonialism will span generations, yet its origins – Canadian backed resource extraction projects such as mining operations – are seemingly erased. When Richardson seeks medical attention, this personal history is overlooked.

Unfortunately, neo-colonial structures are not centered in nursing education and are therefore unknown to nurses, which means that this knowledge does not inform approaches in providing care for Indigenous peoples. To mitigate the cycles of intergenerational harm, Richardson emphasizes the importance of non-Indigenous people understanding the history and violence of colonization and genocide. Nurses are uniquely positioned to gain a deeper understanding of the contexts in which patients present to the health care system and their individual needs regarding care. As such, nurses have increased capacity to create safer spaces for Indigenous people, for example, through cultural safety training. However, for nurses to create safer spaces for Indigenous patients, they must first understand how neo-colonial structures impact health from the perspective of Indigenous people and find ways in which to address this from within western health care.

Book Review #5

Book: Exploring the Intersection of Culture, Health, and the Arts (2021)

Editors: Nancy Van Styvendale, J. D. McDougall, Robert Henry, and Robert Alexander Innes

Book Review Author: Katrina Montinola

The Arts of Indigenous Health and Well-being (2021) is a timely and insightful interdisciplinary collection that explores the intersections between Indigenous culture, health, and the arts. It includes contributions by various Indigenous humanities scholars, social scientists, and artists. The editors, Nancy Van Styvendale, J. D. McDougall, Robert Henry, and Robert Alexander Innes, are white settler, Métis, and Cowessess First Nation scholars, respectively. The book brings Indigenous art, literature, film, music and other arts traditions into conversation.As a student nurse, I found the varied contributions in the book, ranging from ethnomusicology-centred research to performance art analysis, an important way of demostrating the significance of art to health. The book calls attention to the unique health needs and perspectives of Indigenous communities, and how the arts can be used to promote healing, wellness, and resilience.

One of the key strengths of this book is its analysis of Indigenous history in Canada. Several works included in the book highlight the legacy of colonialism and its ongoing impact on the health and well-being of Indigenous communities. However, the resilience and strength of Indigenous cultures and the importance of traditional knowledge and practices in promoting health and healing are also centred. I believe that this collection has much to offer in terms of understanding and supporting Indigenous health from a non-Western viewpoint, which often creates an ideological division between the sciences and the arts. Instead, the authors provide insights into how health and art are closely intertwined, guiding nurses and other care providers to re-evaluate their understanding of the health needs of Indigenous communities.

Nurses can learn much from this book, including how to incorporate Indigenous perspectives into their practice. It also reinforces the importance of cultural safety, building relationships with Indigenous communities, and incorporating traditional healing practices into healthcare. Overall, I found The Arts of Indigenous Health and Well-being to be an inspiring resource for nurses and healthcare practitioners who are seeking to better understand and support Indigenous health. This book provides a comprehensive exploration of the role of the arts in promoting health and well-being in Indigenous communities, and it offers many so-called non-traditional literary works that provide unique Indigenous perspectives that nurses can incorporate into their practice.

Book Review #6

Book: A Cree Healer and His Medicine Bundle (2015)

Author: David Young, Robert Rogers, & Russell Willier

Book Review Author: Jessica Seemann

Disclaimer: The vocabulary used in this book review reflects that used in the source material. The review writer recognizes that vocabulary has changed in the time since this book was published but opts to honour the descriptors chosen by the author at the time of publication to describe himself and his community.

A Cree Healer and His Medicine Bundle: Revelations of Indigenous Wisdom – Healing Plants, Practices, and Stories, published in 2015, is the result of a collaboration between anthropologist David Young, botanist Robert Rogers, and Medicine Man Russell Willier. The book centres on Willier, who was born on Sucker Creek Reserve in what is currently called Northern Alberta. He was raised in the traditional Woods Cree way of life and was given his great-grandfather’s medicine bundle when he was 19 or 20 years old. In the book, Willier shares his journey to becoming a healer, his approach to treating people, and information on traditional medicinal plants, such as their locations and uses. In addition, Willier includes a discussion about the political context surrounding the use and integration of traditional herbal healing practices into modern biomedicine.

A major motivator for the writing of this book, as highlighted in the preface and early chapters, is that Native healers have been passing away without passing on the traditional medicinal knowledge they hold because their children or grandchildren were not in a place where they could take in the traditional knowledge and carry it forward in practice. Furthermore, Willier notes that residential schools were a major contributor to this disconnect, as medicines and languages that were typically passed on orally were lost when children were sent to residential schools. Thus, the next generation’s trust in Native medicines and spirituality has been weakened. This, along with the western healthcare system’s historic suspicion and distrust in the efficacy of native medicine, has created ongoing challenges for the practices that are discussed in this book.

As a result, Willier recognized that he could collaborate with academic researchers to ensure that Indigenous medicinal knowledge would survive the passage of time. It is important to recognize, as the authors do, that colonialism has had a role in creating this situation. In the preface, David Young notes that there were plans to include Willier’s knowledge in an earlier manuscript, however many Native people did not support the inclusion of Indigenous knowledge in a public text because of the long history of European settler expropriation and appropriation of Indigenous knowledge, culture and medicines. As a result, when writing this book, the authors had to consider how to frame the information such that pharmaceutical companies could not exploit this knowledge and use it to create drugs outside of their ceremonial contexts.

How might this book inform the work of healthcare practitioners? There are many valuable suggestions regarding opportunities for collaboration between Indigenous and Western medicine. This book can expand the healthcare provider’s awareness about the multitude of Indigenous medicinal practices and provide insight into the processes that need to occur should patients want to incorporate Indigenous practices into their care plans. As nurses, we can use the teachings of this book to inform our relational practice, provide context for Indigenous treatment plans, advocate for the involvement of traditional healers, and expand the modes of healing available to Indigenous patients. As I move forward in my practice, I will strive to open conversations around the use of such healing practices with my patients by working to create safer spaces that allow for the incorporation of alternative Indigenous healing practices into patients’ care plans.

Thank you for taking the time to read our reviews! We hope we have inspired you to learn more about Indigenous perspectives on health and wellbeing, and Indigenous nursing history in Canada.

References

Burnett, K. (2010). Taking medicine: Women’s healing work and colonial contact in Southern Alberta, 1880-1930. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Lux, M. (2016). Separate beds: A history of Indian Hospitals in Canada, 1920s-1980s. University of Toronto Press.

McCallum, M. J. (2013). Indigenous women, work, and history, 1940-1980. University of Manitoba Press.

McCallum, M. J. (2017, November 30). The how and why of Indigenous nurse history. Nursing Clio. https://nursingclio.org/2017/11/30/the-how-and-why-of-indigenous-nurse-history/

McPherson, K. (2005). The Nightingale influence and the rise of the modern hospital. In C. Bates, D. Dodd, & N. Rousseau (Eds.), On all frontiers: Four centuries of Canadian nursing (pp. 73-88). Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press/Canadian Museum of Civilization.

Wytenbroek, L. & Grypma, S. (2023). The development of nursing in Canada (pp. 34-44). In P. Potter, A. Perry, B. Astle & W. Duggleby (Eds.), Canadian Fundamentals of Nursing (7th Canadian Edition). Toronto: Elsevier.

Wytenbroek, L. & Vandenberg, H. (2017). Reconsidering nursing’s history during Canada 150. The Canadian Nurse, 113(4), 16-18. Retrieved from https://www.canadian-nurse.com/en/articles/issues/2017/july-august-2017/reconsidering-nursings-history-during-canada-150

Follow

Follow